Supplement

Chester the Molester

by Bob Levin

(Excerpt. Most Outrageous: The Trials and Trespasses of Dwaine Tinsley and Chester the Molester. 2008. Seattle: Fantagraphics Books)

The 1960s had promised America revolution. But no New Frontier had been attained or any New Society awakened. People did not ask what they could do for their country instead of what it could do for them. Each did not give according to his ability or receive according to his need. No thousand flowers bloomed. When people came to San Francisco, they did not wear blossoms in their hair. They wore Brioni suits and draped gold chains around their necks and headed for the nearest fern bar.

One area where the Sixties had delivered was sex.

Hustler had ridden the crest of a permissive wave which had swept away resistance to premarital boffing and monogamic insistency. It had left the country awash in sexually explicit books and movies and magazines. It had created employment opportunities for sex surrogates and doctors of human sexuality. It had enriched our language with “glory holes” and “golden showers” and “fist-fucking” (brachioproctic eroticism), the first new act of sexual gratification in eons. In its wake had sprung up anything-goes bathhouses and swingers’ clubs and utopian sex communes and, for all anyone knew, bondage Tupperware parties and S&M picnic groves. The mass-market acceptable Joy of Sex sold two million, eight hundred thousand copies. The X-rated pornography industry was reputed to gross four billion dollars a year. The number of teenage girls who admitted having sex had doubled between 1960 and 1984. (Among those under fifteen, between 1950 and 1975, it had more than tripled).

Of course, these breakthroughs had not gained cultural acceptance as easily as had, say, “The Rite of Spring” or Elvis Presleys hips. One arm of the resistance — that striving to cleanse the nation of porn — was led by two groups that otherwise had as little in common as Janis Joplin and The Singing Nun. Political and religious conservatives of the New Right — organized as the Moral Majority or Citizens for Decency Through Law or Citizens Concerned for Community Values — inveighed against this manifestation of run-amok, libertine self-indulgence for its threat to the moral, ethical and spiritual pillars that were all that elevated society above the primordial muck. (To the conservative columnist David Frum, the turning away from the prairie-virtues of sacrifice and self-restraint that had made this country great, which pornography represented, constituted “the greatest rebellion in American history.”) And radical feminists — Women Against Pornography, Women Against Violence, Women Against Violence Against Women — demanded the abolition of all publications whose denigration of women, they feared, incited men to rape and assault women, and whose reduction of women to dehumanized objects helped perpetuate male social dominance. (To this movement’s media analyst Judith Bat-Ada, Larry Flynt, Hugh Hefner, and Bob Guccione were “every bit as dangerous as Hitler, Mussolini and Hirohito...”)

The anti-porn forces held marches and rallies. They sent letters and signed petitions and disrupted businesses that sold the objectionable and foul. These groups often set Hustler squarely in their sights. The Rev. Jerry Falwell, a leader of the anti-homosexual, anti-abortion, anti-Equal Rights Amendment Moral Majority, believed its calculated program of taboo-defiance made all forms of deviance — drugs, crime, divorce — appear permissible, placing the innocence of American children and the sanctity of the American home squarely at risk. Laura Lederer, a founder of Women Against Violence in Pornography and Media, said that Hustler’s depictions of women shot or stabbed or, on one notorious cover, run through a meat grinder had created “a culture in which real violence against women is not only perpetrated, but accepted as normal.” Lederer specifically singled out “Chester” for its contribution: “Each month,” she wrote, “he molested a different young girl, using techniques like lying, kidnapping and assault.” (She did not mention that he was a character in a cartoon.)

Diana E. H. Russell, a professor of sociology at Mills College, took Lederer one step further. Citing a study which found “a connection between exposure to violent pornography and violent behavior toward women,” Russell wrote that child pornography, because it “commonly portrays children as enjoying sexual contact with adults,” “may create a predisposition to sexually abuse children in some adults who view it.” In other words, because violent pornography had an undefined “connection” with violent behavior toward women, non-violent child pornography might incline some adults to have sex with minors.

A second front in the sexual behavior wars was fought on this neighboring terrain.

In the late 1970s, articles in Forum, Penthouse, of course Hustler, and other, even more scholarly journals had argued in favor of consensual sex between adults and minors — including parents and their children — and recommended lowering the age of legal consent to twelve. (At the time, it ranged within the fifty states between fourteen and twenty. A century before, it had been as low as seven. This still represented an advance over the days of the Talmud, which permitted girls to be married at three.) If you were old enough to want it, one sex education manual bluntly posited, you were old enough to have it. These articles contended that such relations harmed no one and might prove a healthier, more satisfying way to introduce youngsters into erotic pleasures than forcing them to fumble through adolescence with nothing to guide them but the muddled backseat gropings of their peers. Minors were said to gain “status” from relationships with their more amorous elders. They were reported often to be pleased to receive this attention. (Girls were described as being especially “grateful” when their fathers took such interest in them.) The fear of criminal prosecution, it was said, could lead youngsters to stifle normal impulses and inhibit parents from engaging in nurturing hugs and cuddles. To refer to such sexual conduct as “abuse,” the argument went, was to unfairly demean it through the application of a narrow-minded, judgmental, retrograde standard. (Some advocates even cast their argument in Darwinian terms. The initiation of early sexual excitements, they said, would induce a longer period of procreation in the participants, increasing their offspring and the chances for species survival.) In 1975, an article in the prestigious Stanford Law Review, noting the difficulty of distinguishing “appropriate displays of affection” from more “disturbing behavior” — and citing the paucity of studies documenting either short- or long-term “negative effects” of sexual abuse, and expressing concern for the harm that could be inflicted on children and their families by the criminal justice system — advocated the abolition of criminal penalties in all sexual abuse cases involving parents and their offspring.

Needless to say, these views received about as warm a welcome as a pack of syphilitic mandrills at the White House Easter Egg Roll. Child abuse, the opposition countered, was “the cruelest of crimes.” Children were “among the weakest and most defenseless of human beings.” They were “powerless” to effectively consent to adults demanding sex. (Father-daughter sex, in particular, was tantamount to “rape.”) Studies were rapidly marshaled to show that children were inevitably damaged by such experiences. They were subject to life-long guilt feelings, nightmares, depression, self-loathing; left seeking solace in drug and alcohol abuse; programmed to fall into one abusive relationship after another. (Long-term father-daughter sex was deemed especially devastating.)

This debate played out at a time when the sexual abuse of children, in the words of Amy Adler, a professor of constitutional law at New York University Law School, had been recently “‘discovered’ as a malignant cultural secret, wrenched out of its silent hiding place and elevated to the level of a national emergency.’” (It had become, Adler went on to say, “an obsession,” a “passion,” “the master narrative of our culture,” comparable to the Red Scares following World War I and during the McCarthy Era.) This “wrenching” had followed the medical profession’s focusing of the country’s attention on the physical abuse of children a decade earlier through its uncovering of “battered child syndrome,” “shaken baby syndrome,” and “Munchausen syndrome by proxy.” Once the reality of this shame had been established, members of the women’s movement now focused on its more even strongly hidden sister.

These women believed many — some would say most — a few would say all— women had been abused sexually as children. (The extent of this abuse has never been accurately documented. One study, in 1985, put the figure at sixty-two percent — but included exposure to “unwanted” sexual remarks as abuse. Another, a year later, restricted the definition of abuse to forced sexual contact and reduced the figure to six percent. Anti-abuse activists then averaged the two and arrived at thirty-four percent, a figure they found to their liking.) In any event, since girls were unarguably the most frequent victims, speaking out against childhood sexual abuse became a means of speaking up for — and allying one’s self with — the rights of all women.*

* It was also unclear what the consequences of such abuse were. Joan Acocella, in Creating Hysteria, writes there is “little or no research support” for claims that childhood sexual abuse “causes adult psychopathology.” Moreover, she reports, it appears some girls from middle-class homes who suffer abuse actually “overachieve” in life, as if to compensate for the trauma. (However, even if every illicitly fondled girl grew into a marathon-completing MBA from Harvard, with a four-bedroom Tudor in Scarsdale and an orthodontist husband, Acocella would criminally punish the man who touched her.)

These speakers believed that male-dominated societies had conspired to conceal the extent of this outrage. They accused Sigmund Freud of having repudiated his discovery that actual childhood sexual traumas had caused his adult female patients’ neuroses, attributing them instead to the patients’ repressed sexual fantasies, in order to protect the Viennese burghers who had perpetrated these offences. They charged Alfred Kinsey with cooking the books on his research on contemporary sexual behavior to minimize the epidemic of child sexual abuse he had uncovered in order to prevent a backlash against his campaign to rid America of its Puritanical hang-ups. As a result of these fabrications and cover-ups, these women argued, most people had been duped into being skeptical of claims of childhood sexual abuse.

Such skepticism appeared institutionalized within the male-dominated legal system, which seemed to presume that any woman (or girl) who charged a man with sex abuse either desired revenge or blackmail or fame — or was deranged. In 1904, the dean of American evidentiary law John Henry Wigmore had written, “It is time that the courts awakened to the sinister possibilities of injustice that lurk in believing such a witness without careful psychiatric scrutiny.” .Over three decades later, the American Bar Association still recommended that any woman who brought a sexual abuse charge be psychiatrically evaluated to see if she was insane.

By the 1980s, though, things had changed. Suddenly child abuse stories seemed to be in every newspaper and magazine and bookstore. Television talk-show hosts — Phil Donohue, Oprah Winfrey, Geraldo Rivera — spiked their ratings with discussions of this plague. Celebrities energized careers with accounts of their personal victimizations. (Confessions came from, among others, sitcom stars Suzanne Somers and Roseanne Barr, a former Miss America — and Spider-Man.) Abuse charges became as common in child custody battles as boasts about the benefits of competing neighborhood schools. As if to make amends for having overlooked the issue for so long, the press teemed with stories of child brothels, child auctions, and ritualized abuse of children by satanic cults, motorcycle gangs, and entire preschool staffs — sixty-three in the Los Angeles area alone — almost all of which ultimately proved to be unfounded. Under one popular theory, a cult involving Nazi scientists, a Kabala-schooled Jew (“Dr. Green” — formerly “Greenbaum”), the CIA, NASA, and the heads of Fortune 500 companies was involved in victimizing tens of thousands of children. Another implicated some of the same suspects, along with Hallmark Greeting Cards, FTD Florists, and the Jerry Lewis Telethon, in an international ring that had been engaged in gang rapes, infanticides — sometimes by decapitation, sometimes by live burial — and cannibalism for centuries. It had reached the point that, Lawrence Wright reported in Remembering Satan, half the social workers in California believed that Satanic Ritual Abuse not only existed but “involved a national conspiracy of multi-generational abusers and baby killers.” By the mid-Eighties, fifty-to-sixty-thousand satanic murders were supposed to be occurring in the United States annually, despite the fact that no one had been convicted of any of them, the total number of homicides reported for all reasons was less than half that, and investigations by the FBI and the National Center for Child Abuse and Neglect had not turned up evidence of a single one.

Most commentators eventually concluded that these stories were unfounded, attributable to children (or adults) who had been carried away by other traumas or fears or fantasies or whose memories had been polluted by over-zealous therapists or prosecutors. One or two dissenting theorists suggested that clever rings of non-denominational sex deviates may have deliberately spiced their own practices with pseudo-satanic elements in order to discredit any victims who dared report them. Louise Armstrong, author of Rocking the Cradle of Sexual Politics, took hope in a British study of eighty-four reported cases of “organized abuse,” which had found evidence of non-satanic rituals in three, and concluded that future studies might yet “turn up ... [abusers] with ties to pornographers or other criminal elements, or even to some unconventional belief systems.” And others retained a grip on their original belief because of the elusiveness of truth. “We may never know what happened,” the law professor John E. B. Myers wrote about one mass abuse case. “There is no single, simple answer.” “All the questions may never be answered,” the journalist David Hechler echoed. “The full explanation of what occurred [in many cases] may not yet be available.” *

* As I write, no new SRA rings have been uncovered within the United States in over a decade. Some may, therefore, conclude the fiends have become more skilled at concealment.

Within the child-abuse arena, father-daughter incest commanded special attention. For the Harvard professor Judith Lewis Herman, incest — dependent, as it was, upon the authority of the father, the silence of the mother, and the submissiveness of the child — was practically as integral to the dreaded patriarchal family as dad carving the Sunday roast. For the anti-porn crusader Andrea Dworkin, incest was how girls were acculturated to their future role in society. It was, Florence Rush wrote in agreement, “a process of education which prepares them to become the wives and mothers of America.” (Armstrong, from whose book Rushs quote is taken, then posits that the sexual abuse of boys is society’s way of schooling them to abuse girls when they become adults.)

With certain exceptions — the royal families of ancient Egypt and Incan Peru among them — human societies have always condemned incest. (Experts differ about the reason for this condemnation, attributing it variously to a fear of the genetic degeneracies of inbreeding, to a desire to promote stability within the family — or marriage outside it, or simply to establish a behavioral line in the sand, the crossing of which signified utter moral rot.) Every state outlawed incest; but until the mid-1970s, prosecutions were rare. Only a small percentage of father-daughter incest cases were believed to be reported, and less than one-tenth of those resulted in convictions and imprisonment. The private nature of the act made corroboration of the victim’s charges difficult. (In some states, the child was considered a consenting partner or accomplice, making conviction without corroboration impermissible by law.) Many victims were too young to recall events with the specificity successful prosecutions required. Many were pressured by mothers and siblings into recanting in order to keep their families from being destroyed. Many dropped their charges out of embarrassment or a fear of a criminal justice system which, Judith Herman wrote, afforded “more comfort and protection to the male sex offender than to the female victim.” (As examples of this “comfort and protection,” she cited his rights to a public trial, to cross-examine his accuser — and to be presumed innocent.)* And when cases were prosecuted, victims were forced to re-experience the traumas of the abuse — and a defendant’s acquittal could be emotionally devastating for his accuser.

* Louise Armstrong proposed that this last unfairness be balanced by a presumption that all child victims in abuse cases were telling the truth. How else, she wondered, could they receive justice, when their testimony “fundamentally challenges the historical rights and privileges of a patriarchal society... [the] sexual exploitation of children.”

As with general childhood sexual abuse, it was unclear how pervasive father-daughter incest was. Contemporary activists ridiculed previously accepted texts which claimed that only one woman in a million had been an incest victim, preferring more recent studies that put the figure between one in one hundred — or even one in twenty — or ten — or four. (A survey of the statistical studies of incest by Adele Mayer in 1985 found them to be “unreliable and inaccurate and the methodology... fallacious,” with data having been culled from small, skewed portions of the population and then used to support “morally and politically determined conclusions....” Mayer reported that incest had been declared “statistically minor,” when compared to other forms of child abuse, as well as “many times larger,” suggesting that when it came to picking a number in which to believe, the selections were about as great as those on the racks at Loehmann’s.)

Whatever its extent, incest had a compelling grip on the public imagination. It was a staple of a subset of pornography, usually set in good, old, home-as-castle, Victorian days, with fathers boldly rogering their reluctant daughters (or wards). During the swinging Sixties, when incest provided the climax for the black comedy Candy, it was meant to elicit a shocked guffaw; but, by 1975, when its revelation ended the Oscar-winning Chinatown, viewers were expected to gag and shudder. The fact that six of the seven books on the subject I grabbed from the shelf at the main branch of my public library system had been published between 1981 and 1986, suggests that, by Dwaines arrest in 1989, incest was a crime whose time had come.

By the late 1970s, the fear of the consequences of Americas new sexual freedom had led to major changes in its legal system. Local prosecutors became more aggressive in their enforcement of existing statutes and legislative bodies more creative in enacting new, censorious ones. Child abuse laws were expanded to cover even nonviolent sexual acts. The time limit within which such prosecutions could be brought were extended. Zoning ordinances and public nuisance laws were used to curb the spread of adult businesses. Magazines, like Hustler, whose covers were seemingly viewed as capable of converting casual observers into rampaging Visigoths, were ordered sheathed in wrappers of burka-like opaqueness.

The federal government also leaped into the fray. Between 1977 and 1988, Congress enacted a Child Protection Act, a Protection of Children Against Sexual Exploitation Act, and a Child Protection and Obscenity Enforcement Act. It created a National Bureau for Missing and Exploited Children and granted the National District Attorneys’ Association one-and-a-half million dollars to create a center to train investigators and prosecutors to handle abuse cases. Ronald Reagan’s election as president, in 1980, coupled with the Republicans gaining control of the Senate for the first time in decades, seemed to symbolize the triumph of those who desired a return to the calm and soothing, everything-in-its-place, and Lucy-and-Desi-in-separate-beds 1950s. As part of that restoration, a newly convened Attorney General’s Commission on Pornography, embracing the testimony of the feminists and fundamentalists, sought to overturn the conclusions of a presidential commission ten years earlier that no causal relationship existed between explicit sexual material and criminal acts by, among other things, redefining “cause” and relying on its members’ “common sense” rather than scientifically validated evidence.

In 1982, the United States Supreme Court joined this campaign with its decision in New York v. Ferber. Ferber had been convicted of violating a statute which criminalized visual depictions of “sexual acts or lewd exhibition of genitalia” by children under the age of eighteen, through his distribution of a film that showed two teenage boys masturbating. The New York Court of Appeals had reversed his conviction because the film had not been found to run afoul of the existing standard for establishing obscenity, which required that a work, as a whole, be without artistic, political, or social merit. But the Supreme Court held that “the exploitive use of children in the production of pornography” was so great a social problem that states ought to be allowed leeway in combating it.* To assist these states, the court declared pornographic works depicting children ineligible for the protection of the First Amendment of the United States Constitution and held that such works, even if not obscene, could be banned.

* The problem was, according to the court, that the psychological damage caused such children could handicap them in developing into healthy citizens. It is not clear in reading the opinion that the boys in the film whom New York was protecting by prosecuting Ferber were, in fact, from New York — or even America. It is also unclear what evidence had led New York — or the court — to conclude that teenage boys who would masturbate on camera would grow up to be less healthy than those who, for instance, considered the activity a mortal sin.

Congress took advantage of this ruling to enact legislation that outlawed non-obscene but sexually provocative pictures of children — and by raising the age of a “child” from sixteen to eighteen — resulting in nearly ten times as many convictions for child pornography in the next two-plus years as there had been in the prior seven. Lower courts were emboldened to sustain convictions in cases when the child depicted was fully clothed — or if it wasn’t even an actual child being depicted but a representation of one. (The reasoning in these decisions was that the state had the right not only to protect children used in the making of pornography but the children who might be led into sexual acts by being exposed to seductive material.) Such decisions eventually led to criminal prosecutions of nationally known art photographers, a sixty-five year old woman who took nude photographs of her grandson, an NPR reporter researching a story on child porn, and a video-store clerk who rented The Tin Drum to a customer.

This climatic shift in attitudes toward child abuse, as with so many sociopolitical issues in America, seemed to have been effectuated less by studied logic, scrupulous research, and patient wisdom than by a combination of crusader spirit, self-righteous zeal, blind-eyed stupidity, steel-knuckled meanness, inquisition-strength intolerance, star-shine idealism, teeth-chattering terror, and bugfuck looniness. It was also unclear how much it accomplished. Within a decade of the passage of the last bill mentioned above, activists were reporting that not only was the number of confirmed abused children rising by ten percent a year, but the percentage of them receiving aid was declining. And the purported advances in the delivering of punishment to identified abusers often seemed offset by abuses levied by prosecutors pursuing them. The poster child of these cases involved the McMartin Preschool in Manhattan Beach, fifty miles south of Simi Valley, where, in 1983, seven child care workers were charged with abusing three hundred sixty children. Their prosecution took ten years, cost taxpayers fifteen million dollars, traumatized nearly everyone involved, including the children, and, though at one point ninety percent of the population of Los Angeles County was reported to have believed in the crimes’ occurrence, never proved anyone guilty of anything. By 1985, a national organization. Victims of Child Abuse Laws (VOCAL), had been formed, claiming to speak for fifty thousand families damaged by wrongfully brought charges of child abuse. To some commentators, it appeared the country was being suckered into focusing on the statistically minor problem of child sexual abuse to distract it from the elimination of social programs, the effect of which has been to condemn twelve million children to lives of poverty, without adequate health care, nutrition, education, housing, or a likelihood of economic betterment.* “It is wrong to single out sexual abuse as the worst harm to children,” wrote Judith Levine, one of these commentators, when in the United States, “child abuse is business as usual.”

* A study a decade later reported that children in families with annual incomes of under fifteen thousand dollars were twelve-to-sixteen times as likely to be abused physically — and eighteen times more likely to be abused sexually — than those with family incomes of thirty thousand dollars.

. . .

|

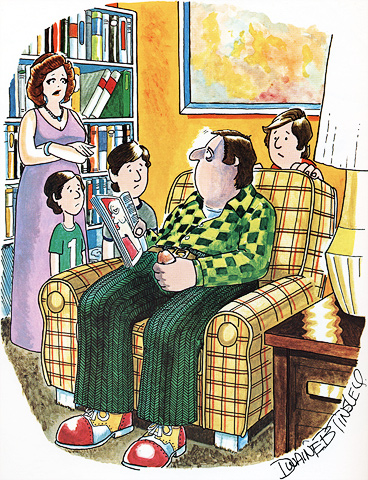

“Honestly, Newton, do you really think this is the time

or the place to show the boys how to masturbate?” |

Hustler, January 1976, Dwaine Tinsley, p. 78 |

By late 1975, Dwaine's work was appearing monthly in Hustler. His page rate had progressed from one hundred, to two hundred, to two hundred fifty, to three hundred fifty dollars for a full-page color cartoon. His personal grievances and grudges, his resentments and furies easily blended with those that fueled Larry Flynt. His cartoons excoriated politicians and preachers and the rich. They raked blacks and Hispanics, Arabs and Jews. They found humor in amputations, bestiality, blindness, enemas, farts, necrophilia, nose pickings, paraplegia, and sex dolls. He drew exterminators using a Negro baby to lure rats from hiding. He drew a husband exclaiming to his wife who has caught fire in the kitchen, “Aw shit! You burned supper again.” He drew one derelict crapping into a bag, while another offered it for sale as “dog food.” He drew a minister praying for a young woman congregant to be saved — as soon as she finished fellating him. But Dwaine’s most significant contribution to Hustlers gut-shot effrontery followed his recognition that most successful cartoonists had one memorable character at their command. So, spinning off from Buck Brown’s Playboy granny, who lusted after young men, Dwaine produced a leering, overweight, blond fellow, dressed in saddle shoes and herringbone slacks, who carried a baseball bat and craved prepubescent girls. He named him “Chester,” after Chester Gould, the creator of Dick Tracy, and “the Molester” because, well, as he put it, “the Dirty Old Man lacked snap.”

Chester made his debut February 1976, with a hand puppet on his penis, inviting a young girl to “give widdle Rodney a kiss-kiss.” He seems to have derived from a similarly garbed and shaped, dark-haired fellow named “Newton,” who had appeared the month before tutoring his sons on the fine points of self-abuse, while his disconcerted wife looked on. In March, he was excitedly reading Hansel and Gretel while lurking in an alley, his bat at the ready. In April he was asking a hotel desk clerk for a room with a waterbed for himself “and... uh... my daughter.” During the next two years, Chester was seen asking a mother if little Alice can come out and play; in bed, composing a letter that begins “Dear Kinky Korner,” while surrounded by several bound girls; lying beneath a children’s slide with his tongue primed for the girl at the top; attempting to lure a Jewish girl into an alley with a dollar bill tied to a string; in drag (with ball bat), at the White House, being introduced as Amy Carters new babysitter; at the manger, beside baby Jesus, exclaiming, “Aww shit! It’s a boy”; disguising his penis as a hot dog, a flower bouquet, an American flag (for the Fourth of July), and a bobbing apple (for Halloween) while offering it to various little girls’ hands or mouths.*

* Even Hustler had its standards. In these years, its cartoonists were forbidden to show insertion or people actively engaged in bestiality or sexual acts with children.

Dwaine, himself, was never a cartoonist to lead a reader off-message with a panel’s visual delights. His standard offering was some pleasant colors, some basic elements to establish scene — a carnival midway or city street — an emotion economically conveyed through eye angles or perspiration drops and, then — WHAM!!! — the sock of a central gaping vagina — or gigantic cock — or anus on legs. And with that image came a point. “You could feel his cartoons,” Trosley says. “Dwaine believed in them, so he thought them through fully. He had a genuine love for the art of cartooning and the ability to get a laugh from anyone — and combine that laugh with a twinge of pity or sadness. With a cartoon, you expect the laugh, but if you can also mix in a lesson, so that someone walks away enlightened, you feel successful. You know, like when you’re in a convenience store and taped to the cash register with forty pieces of tape is this old cartoon? That means it meant something to a person, and he wanted to share it.”

In the spring of 1978, Chester had been recast as “Chester the Protector.” (Dwaine had protested publicly against his creation being neutered “into some kind of Zorro for Christ” — but he was reminded of his paycheck’s source.) That Chester wielded his bat against physically abusive parents, schoolyard drug pushers, vermin menacing inner city children, even an older man coming onto a young girl in an ice cream parlor. (The man resembled Charles Keating, a leading anti-pornography crusader.) When Flynt’s conversion into Christianity lapsed, though, Chester reverted to his socially unredeeming ways. But now his focus had broadened. The harbinger of this awakening, Hester — tall, skinny, outfitted in an assortment of fetishistic gear — appeared in his doorway in November 1978. “Hi, Sugar,” she announced, as hearts floated above their heads, “I’m the girl from the computer dating service...”

“Chester and Hester” lasted four years. Dwaine’s sources of humor now expanded to include vinegar douches, chicken suits, smelly underwear, prostate massages, and one partner lying beneath a glass table while the other defecated upon it. Then, in November 1982, Hester vanished and “Chester the Molester” returned — but with desires beyond young girls. He had not renounced them entirely — in one memorable moment, he attempted to lure a blind girl into his clutches by dangling a steak in front of her seeing eye dog; in another, he masturbated to pictures of missing children on a milk carton — but the objects of his lust now included cats, poodles, sheep, an organ grinder’s monkey, a teddy bear, nuns, and a vacuum cleaner. He had become, Dwaine would explain, “a broader parody of sexuality.”*

* In Dwaine’s view, his Late Chester period represented a maturation on his part. “As creative people grow older,” he wrote — about these poodles and vacuum cleaners — “they become mellower, ...more conscious and finer tuned in their work. They round off the rough edges of youthful exuberance.”

It should be noted that, except in his “Protector” phase, Chester was never portrayed as someone to be admired or emulated. (To make this clear, Dwaine once hung a Nazi flag from Chester’s pecker.) He was not physically attractive. (“Loutish” is the first adjective his appearance brings to mind.) He was not even particularly successful. (To be blunt, he never achieved penetration — let alone orgasm — with any of his prepubescents.)* He always ranged within a characterological spectrum between the ridiculous and the depraved. (In Dwaine’s terms, Chester was “a ludicrous sexual outlaw” in pursuit of “anything with an orifice.”) Certainly, his choices for gratification would have appalled most people. Certainly, even most of those open-minded enough to have found humor in his hungers shook their heads in disapproval while they laughed.

* In this regard, Chester lagged far behind, not only Lolita, but the underground comics of the late 1960s, most notably the work of R. Crumb. See, for instance, his notorious “Joe Blow,” in Zap #4, whose inter-family frolics had vendors busted from New York to California.

But there is humor in these cartoons — and it is humor with a social value. Dwaine would defend Chester on the grounds that he focused attention on a major societal problem or that he satirized the consequences of uncontrolled sexual desires, but I believe the value of these cartoons is both deeper and more subtle. What seems significant to me is the extent of outrage provoked by Dwaine’s selection of this topic as a subject of humor. It may be that one of the nobler — and more courageous — functions of art and artists is the probing of societies for tender points. Does it bother you here, such art asks. What about here, it inquires. When society yelps, the artist may have found an area that warrants further exploration. For art is only words and pictures; and if it causes discomfort, those areas may benefit from open airings. What are you hiding, the artist asks. Why are you hiding it? Would you care to discuss it?*

* The argument against this position is that certain expressions are so repugnant to a society’s core beliefs, values, customs, and traditions that they cannot be permitted lest they destroy all that binds that society together. The counter-argument to this position is that its implementation did not work out so well for Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia.

“As a cartoonist,” Dwaine Tinsley said, “I’m going to make you laugh or make you mad or make you think.” “Hustler cartoons,” he said, “allow people to laugh at the taboo, the sacred and the controversial.... Most people laugh at our cartoons, feel guilty about laughing, and end up thinking about it for years — that’s impact!” It was also, he recognized, “art.” He was saying, in effect, that there is value in the most foul and repugnant, as there is value in me.

Of course, the portion of this contribution that provoked the most thought and laughter and anger — that took the most courage and in which he invested the most pride — was Chester. Dwaine had not planned to tread the tightrope walk above the razor-bottomed pit of time that is a career hand-in-hand with a ball bat-wielding pervert; but he had pursued his artistic vision, and his vision had produced Chester. If he took his art seriously, which he did — which he certainly did — it was his responsibility to push it to extremes, to grind Chester against the most noses, to fling him into the most eyes. Any serious artist works out of a belief that the virtue of his devotions will bring him rewards. If he is an artist who works in the stuff of outrage, he knows he may also be reviled. And while he may have hope for an ultimate payoff, he can t know in advance the outcome — if his faith may equal hubris — what jackpot exactly is in the mind of the gods. (They may be black humorists too.) “He had followed his extraordinary destinies through to the end,” Yasunari Kawabate wrote in The Master of Go. “Might one also say that following them meant flouting them?”

. . .

The vectors of anti-pornography and anti-child abuse thought converged upon Dwaine Tinsley as a perfect storm through the work of Judith Reisman, PhD. (The former Judith Bat-Ada, Reisman had previously been best known for accusing Alfred Kinsey of torturing children as part of his “research” while pursuing a secret agenda of acclimating the public into accepting homosexual and pedophilic behavior.) In November 1983, the Reagan Justice Department, through its Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, commissioned Research Project No. 84-JN-AV-K007, with Reisman as Principal Investigator. The project cost seven hundred, thirty-four thousand dollars and resulted in a three-volume, two thousand-page report, entitled Images of Children, Crime and Violence in Playboy, Penthouse and Hustler.

Reisman and ten associates studied six hundred eighty-three issues of these magazines. They established that they commingled forty-four thousand visual representations of adult female nudity (thirty-five thousand breasts and nine thousand genitalia), six thousand visuals of children, and fifteen thousand of crime and violence, for twenty-five million readers a month.* This melange’s blurring of age distinctions, Reisman argued, made children “more acceptable” as objects of sexual desire for adults and provided these aroused adults glossy, readily available aides “to lure and indoctrinate” children into performing sexual acts. The cartoons in these magazines, she said, played a particularly insidious role in this process. Cartoons were accessible to and popular with children. Because they appeared “light and guileless,” cartoons could humorously trivialize societal taboos, enabling them to slip through normal resistances, arousing their viewers’ sexual interests and legitimizing their sexual behavior. Hustler, Dr. Reisman calculated, had about twice as many such images a month as Playboy or Penthouse. And the cartoonist she identified as the chief offender, with one hundred forty-five black-marks to his credit, was Dwaine B. Tinsley. The runner-up had ninety.

* Playboys circulation was about fifteen-and-a-half million, Penthouses seven million, six hundred thousand, and Hustlers four million, three hundred thousand; one would expect some duplication of readership. (By way of comparison, Ms. had a circulation of one million, six hundred thousand. Vogue five-and-a-half million, and Sports-Illustrated thirteen million.)

John Heidenry, the sex historian, has called Images of Violence “the biggest anti-pornography boondoggle of the century.” It was so unpersuasive that the Justice Department refused to release it. (Reisman charged that this suppression was the work of the sex industry’s previously undocumented “deep personal and economic ties to the conservative movement, the Reagan Administration and the Republican party.”) Her thesis did not even seem to fit Dwaine’s situation. As the creator of Chester, not the consumer, he presumably had the images that became his cartoons in his head, proud and whole, and did not need to see them on paper to have them made “acceptable.” And little in the acts he depicted seemed likely to “lure” children into participating in them. Chester was an unpleasant fellow and his girls generally stunned or shocked by what he had in mind for them. They were clearly to be seen as victims, not fellow-revelers. Yet the Ventura County district attorney’s office would herald Reisman’s report as “a great piece of work,” and it would be crucial to its approach to Dwaine and Veronica, his nineteen-years-old daughter who on May 17, 1989, accused him that he had molested her for six years. A person sympathetic to Dwaine’s claim of innocence, might have concluded that a PhD’s mingling, through footnote-bolstered print, of Hustler cartoons and child sexual abuse had made the guilt of a Hustler cartoonist charged with such crimes seem inevitable to those inclined to convict him anyway — that the Reisman report had lured and indoctrinated the district attorneys office into prosecuting charges of which others might have been more skeptical.

. . .

Dwaine had spent his last dollar — and a hundred and eighty thousand borrowed from Larry Flynt (at ten percent interest) — on his defense. Because he could no longer afford a lawyer, the California Appellate Project, a non-profit organization that represented indigents, handled his appeal. CAP assigned him to Vanessa Place, a 1984 graduate of Boston University Law School. She had been on staff only a year and had handled fewer than a dozen cases. Her supervisor had thought this one’s difficulty would make it a valuable learning experience.

Places first reaction was that Dwaine’s chances were not good. Criminal convictions were rarely reversed. In he-said/she-said sex crimes, jurors almost always believed the victim; and appellate courts were loath to second-guess them. Even Eskin’s argument that the cartoons had prejudiced the jury seemed weak. Crime-scene photographs so gory they could only set a jury screaming for equal blood regularly came into evidence, whether the butchery they documented was disputed or not. In Place’s view, criminal trials were often unfair; but reviewing courts regularly brushed aside this unfairness as inconsequential. “I thought, ‘No chance,”’ Place recalls. ‘“You’re representing Chester the Molester. Who’s less likely to get a reversal than him?”’

Then Place went to the Ventura County courthouse and saw the boxes of magazines that had been the prosecution’s evidence. “The smartest thing I did,” she says, “was to have all those cartoons transferred to the Court of Appeal.” She had recognized that, in the abstract, the terms “shock” or “offend” could mean little; but most people, face-to-face with thirty-two hundred cartoons, whose entire point was the jamming of a horse-cock down society’s throat, would be outraged or revolted; and it was likely the justices would too. For Place, the cartoons were no more relevant to the charges against Dwaine than the contents of an architect’s files would be to similar charges against him. They were simply the product of a fifteen-year career, ideas transferred to paper to satisfy an employer and meet a market’s demands. “But the way the prosecution had presented it, it was, ‘This is a bad guy. Look at the creepy things coming out of him. These are the outpourings of a pervert, an all-around soulless person.’”

She was gambling that the justices would be jarred by their reaction to the cartoons into realizing that no juror who had seen them could view their creator with the presumption of innocence a fair trial required. The risk was that the justices would become so incensed themselves they would gleefully tighten the noose around her client’s neck.

On February 22, 1991, Place filed her opening brief in the California Court of Appeal’s Second Appellate District in Los Angeles. The case was assigned for hearing to a three judge panel, the composition of which appeared both hopeful and problematic for Dwaine. Two of the justices, Arthur Gilbert and Steven J. Stone, had been appointed to the bench by Jerry Brown in 1980. They had established reputations as excellent, progressive-minded jurists — but they were also close friends of Judge Storch, whose decision they would be reviewing. And the third justice, Kenneth R. Yeagan, had been appointed in 1990 by the Republican governor George Deukmajian. As a trial judge in Ventura County, Yeagan had been considered very conservative in criminal matters.

Place first argued to the panel that Dwaine’s conviction should be reversed because any probative value the cartoons had cast had been overwhelmed by the prejudice they spawned. The prosecution, she noted, had first justified the cartoons’ admission on the grounds that they had demonstrated Dwaine’s “intent” and “overall scheme.” It had then claimed he had used them to induce Veronica to have sex. Finally, it had “collapsed” these two claims into the argument that they documented the Tinsley “lifestyle of incest.”

But, Place said, the only intent the cartoons established was Dwaine’s wish to make a living as a cartoonist. In any event, intent was not an issue. Dwaine’s defense was that the events had not happened, not that they had occurred by accident — not that he had mistakenly slipped his penis between Veronicas lips. If the jury had believed her, his intent would have been established, regardless of what fantasies his cartoons expressed. If the jury had believed him, these fantasies would have been irrelevant since no crime would have occurred. (Place contrasted Dwaine s situation with the defendant’s in People V. Stewart. There, the court had allowed into evidence photographs of him sexually molesting his daughter because these photographs showed his “lewd disposition” toward his specific victim. But Dwaine s cartoons revealed nothing about his attitude toward Veronica.) The cartoons did not establish any “scheme” of Dwaine’s because there was none to establish. They captured no “bizarre details [of] or striking similarities [to]” the crimes of which he had been accused. And, unlike People v. Haslouer, where the defendant had shown young girls playing cards that depicted assorted sex acts and asked them to pick one to perform, there was no evidence that Dwaine had used his cartoons to make Veronica do anything. Finally, Place referred the justices to People V. Valentine, in which the conviction of a man charged with marijuana cultivation had been reversed because the state had introduced into evidence a hypodermic needle and syringe found in his home. That court had ruled Valentine’s involvement with one type of drugs did not tend to prove his involvement with another. Similarly, Place said, Dwaine’s involvement with one form of socially questionable behavior — the creation of transgressive cartoons — no matter how extreme — should not have been used to convict him of abusing his daughter. The prosecutions Chester the Molester “lifestyle” theory, she said, was clearly improper. It was “simply a sociological buzzword posing as an evidentiary justification... an attempt to camouflage the prosecutions primary motive for introducing this material,” which was to “deluge” the jury with thirty-two hundred cartoons of abortion, bestiality, defecation, feces, mutilations, and racial and religious defamation. “Whatever probative worth the drawings may have had,” she said: “they were not introduced for that purpose.... [T]he manifest rationale for admission was the states thesis of guilt by creation.... These cartoons were guaranteed to prejudice appellant’s jury. Virtually every segment of the population would have found something in these cartoons denigrating their group or some cherished belief.”

Then Place raised her argument into a higher realm. The First Amendment to the United Stats Constitution, she reminded the court, had established freedom of speech as a defining aspect of our national identity. For free speech to flourish, it had to be protected from governmental efforts to stifle it at whim. And Dwaine’s cartoons, while outrageous and offensive and, perhaps, even “immoral,” were within the class of speech which the First Amendment valued and protected most. His work was not frivolous; it did not pander; it was not compromised to court the easy buck. It was politically and socially engaged. “Appellant,” Place wrote, in what may have been the first — and most astute — critical analysis of Dwaine’s work ever written: “skewers sacred cows. He attacks what he sees as hypocritical social mores, religious pretense, racial sensitivities, and sexual peccadilloes. He chronicles the ludicrous machinations in which man will engage to satisfy his sexual desires, and the breadth of those desires. More fundamentally, [he] rips the cloak of civility from private habits and practices, confronting man with the absurd humiliation of his most primitive functions, and mocks that humiliation, exposing as false the pride that causes us to blanch. [His] drawings celebrate the disgusting and embrace the repugnant, reveling in the uncomfortable fact that man is, after all, only human.”

By using Dwaine’s cartoons against him. Place said, the state had not only improperly imposed itself on one side of a sociopolitical debate, it had made his expressions of unpopular ideas appear indicative of criminal acts. If it was allowed to hang Dwaine with a rope woven in part from his creations, all artists would be discouraged from describing, in song or film or on the printed page, actions that might be used against them by other vengeful district attorneys.

Place was no First Amendment “absolutist.” She would allow even clearly political speech to be curtailed. But, she said, for the state to use speech that would otherwise be protected by the First Amendment as evidence a speaker had committed a crime, there must be “an overriding and compelling” governmental interest justifying this infringement; and “stringent procedural safeguards” must exist to insure that the infringement is “no greater than necessary to serve that interest.” “The evidentiary door [should be opened only]... the slightest crack necessary... to limit admission of First Amendment protected materials to only those which are substantially relevant to the state’s case.... [Here] the door was blown off its hinges.”

In California, responses to appeals of criminal convictions are the responsibility of the state’s Office of the Attorney General. Deputy attorney general David F. Glassman, who had joined the A.G.’s office shortly after graduating Loyola Law School in 1983, filed his on August 1st.

The cartoons were relevant, Glassman said, for they were “used by appellant to perpetuate his crimes.” He regularly allowed Veronica to watch him draw them. He showed them to her every month. He discussed them with her. He permitted her “unlimited access” to his studio, where she could view them at her leisure. He provided her collections to give her friends. Since many of these cartoons showed sexual relationships between adult men and young girls, they were clearly used to “indoctrinate” Veronica into accepting such relationships as appropriate and “facilitate” her having sex with him. Furthermore, since Dwaine had created the cartoons, they provided striking evidence of his intent. The behavior that consumed Dwaine at his drawing board was the behavior he inflicted upon Veronica.

Glassman cursorily dismissed Places First Amendment argument. Dwaine was, he said, neither prosecuted nor punished for his speech. A voluntary confession would not be excluded from evidence on free speech grounds. Neither would a painting depicting a stabbing an artist had committed or a novel describing how an author had planted a car bomb. Similarly, here, the cartoons were relevant to prove the commission of a crime.

Places reply was even more succinct. Glassman, she said, missed the point. The question was not if protected speech was admissible evidence in criminal cases, but what standard determined its admissibility. She believed the speech had to be “substantially relevant;” and, unlike a confession, whether verbal or on canvas, these cartoons were not.

Place said the states “leap of faith” in its theories of relevance “simply [did] not fly.” There was no basis for its conclusion that creation of a work was probative of intent to perform an act expressed within it. Nor did the fact that Dwaine showed Veronica some cartoons and did not prevent her looking at others mean he had used them to commit a crime. This constituted “pretend proof,” “daubing on an evidentiary gloss to support an unsupportable theory of admissibility.” (Place also pointed out that Dwaine’s “use of the older male/younger female theme... was hardly an original or even particularly interesting sin.” If it was to be used to convict him, then Jane Austen (Emma), George Bernard Shaw (Pygmaliori), and Louisa May Alcott (Little Women) might also be said to have aided and abetted felonies.)

And how, she asked, did any of the states arguments justify showing the jury the cartoons that dealt with feces, cannibalism, racial stereotypes, and dead fetuses?

On February 25, 1992, the court, in an opinion written by Justice Stone, unanimously reversed Dwaine’s conviction on the grounds that the cartoons had prejudiced the jury.*

* Because of this holding, the court did not have to address Place’s First Amendment argument. “It didn’t want to hear it,” she now says. “It just wanted me to focus on the prejudice. I thought it was pretty good. It had me very excited. But I had no takers.”

The prosecution, the court said, had presented no evidence that Dwaine had used the cartoons to induce Veronica to have sex with him. All it had proved was the existence of the cartoons and, according to Veronica, the sex. The fact that she had seen the former in his studio, however, failed to establish that they had led her into the master bedroom. No expert had testified that this was a likely effect of such cartoons on such an adolescent. Even Veronica had been unable to specify which cartoons she had seen, when she had seen them, or how they had affected her. She had not even said that her father had shown or discussed with her the one cartoon that depicted an incestuous relationship. Indeed, the court noted, there was no evidence that, when it came to sex, Veronica required inducement. Her own testimony was that it had been sufficient for her father to ask.

The prosecutions inducement argument, said the court, was “disingenuous,” not only because it had produced no evidence to support it, but because, at trial, it had repeatedly used the cartoons to attack Dwaine’s “lifestyle.” The prosecutions position seemed to be that anyone depraved enough to have created these cartoons would be depraved enough to sexually debase his daughter. But it was basic law that evidence of a persons character could not be used to infer his likelihood to commit a crime.

Still, the court went on, not every evidentiary error warranted the reversal of a conviction. The critical question became whether the error had caused “a miscarriage of justice.” In answering this question, the court dismissed Judge Storch’s reasoning that nothing significant could have resulted from any error he may have made because the jury had acquitted Dwaine of more charges than it had convicted him. If he was acquitted of that many counts, the justices wondered, why was Dwaine convicted of any? The evidence on all the charges was equal. On each the jury was asked to weigh his credibility and character against Veronicas. The inescapable conclusion was that the cartoons had so outraged the jurors that they had decided he had to be guilty of something. “[I]t is reasonable to conclude” the court said, “that the cartoon evidence tipped the scales of justice against appellant.... [I]t is not reasonably probable that the same verdicts would have resulted had the repugnant cartoons not been admitted.*

* When I reported to Vanessa Place the statement by Roy Sherman, the jury foreman’s, about the role played by the cartoons in persuading him of Dwaine’s guilt, she responded, “So, justice was done.”

In a separate, concurring opinion. Justice Yeagan, the judge about whom the defense had been most concerned, went out of his way to express his dissatisfaction with the prosecutions conduct. The district attorney, he wrote, “should have recognized the potential for reversal” in urging the cartoons into evidence. Prosecutors, as well as judges, must protect defendants’ constitutional rights. Their job is not simply to convict. They have an “entirely separate duty” to insure that trials are fair.*

* Some who had viewed Dwaine’s conviction as proof of Hustlers fetid soul were disinclined to trumpet this decision as a blow in favor of individual freedoms and against a treacherous state. He had escaped, the Mills professor Diana E. H. Russell sneered, via “a legal technicality.”