The term “aggression” has been defined as behavior in which one or several individuals injure and threaten or try to injure another (McKenna, 1983). Aggressive behavior is inevitably accompanied by a reaction. The reaction may be aggressive, or it may be submissive. We also use the term “agonistic” behavior for behaviors exhibited by both aggressor and victim.

The aggressive behavior pattern of pygmy chimpanzees abounds with variety, from violence, including physical contacts such as biting, hitting, kicking, slapping, grabbing, dragging, brushing aside, pinning down, and shoving aside, to glaring, bluff charging (the appearance of charging), charging, and chasing. A pygmy chimpanzee may also approach another with exaggerated gestures, wave his arms around the other’s head, and leap over the other’s body, threatening body contact. Aggressive behavior is accompanied by a vocalization that sounds like “kat-kat.”

Prostration, grimacing, flight, avoidance, extending one’s hands, and touching the other’s body are classes of submissive behaviors in response to aggression. Three kinds of shrieks are emitted by victims. They are, in order of increasing intensity, “gyaa-gyaa,” “kii-kii,” and “ket-ket.”

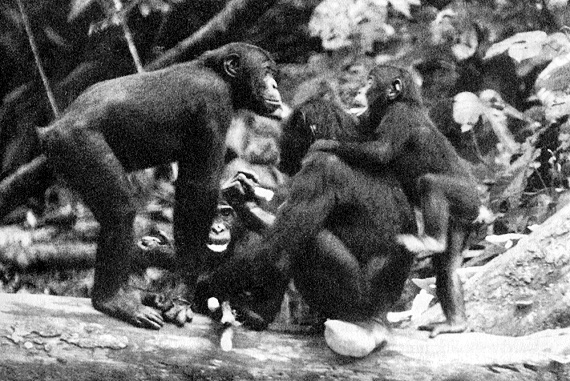

Low-level aggressive interactions, such as approach-avoidance or bluff charge-flight, occur very frequently between males and seldom involve other patterns of behavior. Furthermore, the aggressor and victim are constant; that is, the victim and aggressor do not switch roles.

Aggressive interactions mainly occur at feeding time and, most often, when individuals gather in the trees to feed on concentrated foods such as Dialium and batofe. This suggests that proximity between individuals may induce aggressive behavior.

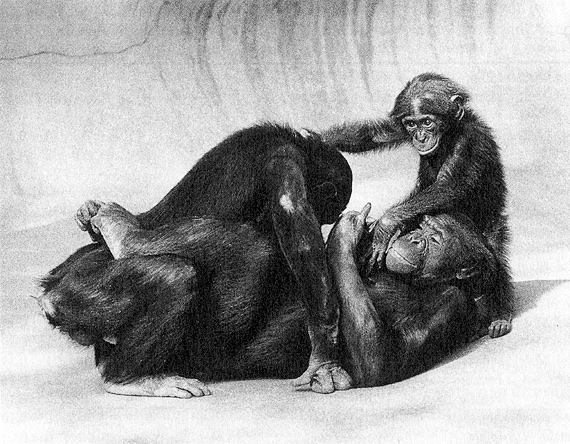

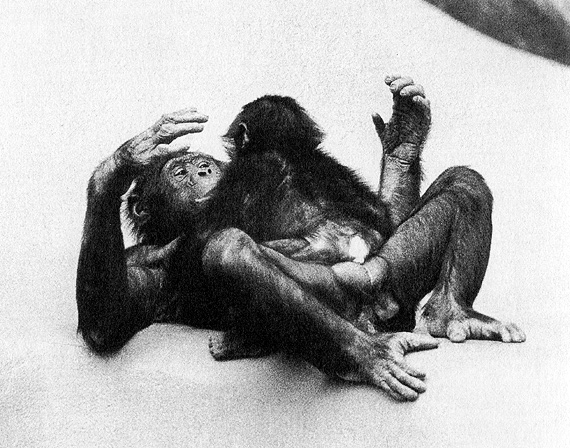

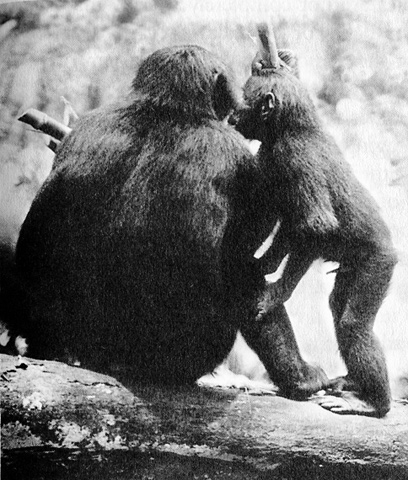

Successive mounting or rump-rubbing often occur during aggressive interactions. Mounting is riding horseback on another, taking the position used in dorsal copulation. In rump-rubbing, two individuals in a “presenting” posture direct their rear ends toward each other and press their buttocks against each other. Sometimes the positions are assumed and held motionless, but usually they are accompanied by slight rhythmical thrusting movements. Frequently, both actors have erect penises, but insertion into the anus during mounting has not yet been verified.

Figure B. Two males rump-rubbing. Photo by Takayoshi Kano.

In an aggressive interaction, the attacker may spring on a male who, cut off from escape, is groveling and screaming, and the attacker will mount or rump-rub the victim. Or, the attacker may confront his victim, suddenly facing the victim’s buttocks and demanding mounting or rump-rubbing. The order of these events is not fixed.

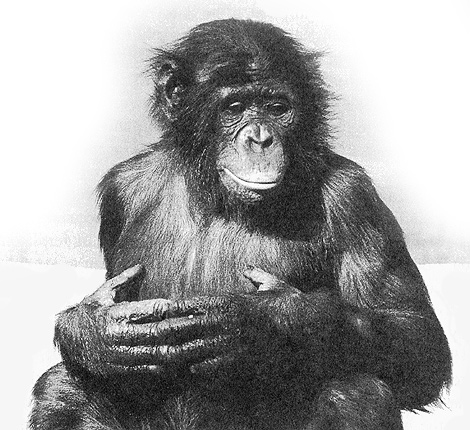

Figure C. A male grimaces while mounting a higher-ranking male. Photo by Takayoshi Kano.

Immediately after arrival at the feeding place, a male may make a gesture similar to a sexual display to another male, and then, either mounting or rump-rubbing may occur. Mounting and rump-rubbing may have the same function because the social context in which they occur is practically the same. These actions put an end to aggressive interactions, preventing anything injurious from happening, and have the effect of '‘appeasement” or “pacification.” The dominant male presents a guarantee of safety to the subordinate.

(Kano)