<<< >>>

{83}

Chapter 3

Two Hundred Years of Looking at Homosexual Wildlife

1764: ... three or four of the young [Bantam] cocks remaining where they could have no communication with hens ... each endeavoured to tread his fellow, though none of them seemed willing to be trodden. Reflection on this odd circumstance hinted to me, why the natural appetites, in some of our own species, are diverted into wrong channels.

— GEORGE EDWARDS, Gleanings of Natural History

1964: Another example of an irreversible sexual abnormality concerns an orang-utan. This ape, a young male, was kept with another young male and they spent a great deal of time playing together. This included some sex play and anal intercourse was observed on a number of occasions.

— DESMOND MORRIS, "The Response of

Animals to a Restricted Environment"

1994: There are several explanations for homosexual behavior in non-human animals. First, it is possible that the pursuers misidentified male 42 as a female because the plumage of after-second-year female Tree Swallows resembles that of males ...

— MICHAEL LOMBARDO et al., "Homosexual

Copulations by Male Tree Swallows"1

{84}

Animal homosexuality is by no means a "new" discovery by modern science. Some of the earliest statements regarding homosexual behavior in animals date back to ancient Greece, while the first detailed scientific studies of same-sex behavior were made in the 1700s and 1800s. From the very beginning, descriptions of homosexuality in animals were accompanied by attempts to interpret or explain its occurrence, and observers who witnessed the behavior were almost invariably puzzled, astonished, and even upset by the simple fact of its existence. As the quotes above illustrate, many of these same attitudes have continued to this day. With more than 200 years of scientific attention devoted to the subject, how is it that so many people today — many scientists included — are unaware of the full extent and characteristics of animal homosexuality, and/or continue to be puzzled by its occurrence? This chapter seeks to answer this question, first by chronicling the history of the study of homosexuality in animals, and then by documenting the systematic omissions and negative attitudes of many zoologists in dealing with this phenomenon. As we will see, a history of the scientific study of animal homosexuality is necessarily also a history of human attitudes toward homosexuality.

A Brief History of the Study of Animal Homosexuality

The history of animal homosexuality in Western scientific thought begins with the early speculations of Aristotle and the Egyptian scholar Horapollo on "hermaphroditism" in hyenas, homosexuality in partridges, and variant genders and sexualities in several other species.2 Although much of their thinking was infused with mythology and anthropomorphism, and there are notable inaccuracies in their observations (the Spotted Hyena, for example, is not hermaphroditic), the discussions of these scholars represent the first recorded thoughts on homosexuality and transgender in animals. The earliest scientific observations of animal homosexuality are those of the noted French naturalist (and count) Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon, whose monumental fifteen-volume Histoire naturelle generale et particuliere (1749-67) includes observations of same-sex behavior in birds. Additional observations on homosexuality in birds were made in the eighteenth century by the British biologist George Edwards, and (as indicated above) they also include some of the first pronouncements about the supposed "causes" and "abnormality" of such behavior.3

The beginning of the modern study of animal homosexuality was heralded by a number of early descriptions of same-sex behavior in insects (e.g., by Alexandre Laboulmene in 1859 and Henri Gadeau de Kerville in 1896), small mammals (e.g., by R. Rollinat and E. Trouessart on Bats in 1895), and birds (e.g., by J. Whitaker on Swans in 1885 and Edward Selous on Ruffs in 1906), while the German scientist Ferdinand Karsch offered, in the year 1900, one of the first general surveys of the phenomenon. 4 Since then, the scientific study of animal homosexuality has expanded enormously to include a wide variety of investigations, reported in close to 600 scientific articles, monographs, dissertations, technical reports, and other publications {85}

in over ten different languages. These range from field observations of animals that only anecdotally mention homosexual behavior, to more extensive descriptions of homosexuality in a wide range of species studied in the wild, to observations of captive animals (including at many zoos and aquariums throughout the world), to experiments on laboratory animals, to more recent studies devoted to examining all aspects of homosexual behavior in a particular species (often in the wild), to more comprehensive general surveys of the phenomenon. Some reports have received wide attention, such as the discovery of female pairing in various Gull and Tern species that initiated a flurry of scientific and media interest in the late seventies and early eighties. On the other hand, many reports of animal homosexuality have gone unnoticed even by other zoologists, languishing in small specialty or regional journals such as The Bombay Journal of Natural History, Ornis Fennica (the journal of the Finnish Ornithological Society), Revista Brasileira de Entomologia (the Brazilian Journal of Entomology), or the Newsletter of the Papua New Guinea Bird Society. In a few cases, well-known scientists have published descriptions of animal homosexuality, including Desmond Morris on Orang-utans, Zebra Finches, and Sticklebacks, Dian Fossey on Gorillas, and Konrad Lorenz on Greylag Geese, Ravens, and Jackdaws. 5 Aristocracy has even been involved: in addition to Count Buffon's observations in the eighteenth century, in the 1930s the Marquess of Tavistock in England coauthored a report on bird behavior with scientist G. C. Low that included descriptions of same-sex pairs in captive waterfowl. Like Desmond Morris's account of same-sex activity in Orang-utans quoted above, however, his report was somewhat less than "objective," containing as it did a statement about how "ludicrous" were a pair of male Mute Swans that remained together and built a nest each year.6

While most scientific studies of homosexuality in animals have simply involved careful and systematic observation and recording of behavioral patterns (occasionally {86}

supplemented by photographic documentation), in some cases more elaborate measures have been employed. The study of animal behavior has now become extremely sophisticated and even "high-tech," and many of these techniques have been applied with great effect to the recording, analysis, and interpretation of same-sex activities and their social context. DNA testing, for example, has been employed to ascertain the parentage of eggs belonging to lesbian pairs of Snow Geese, to determine the genetic relatedness of female Oystercatchers and Bonobos who engage in same-sex activity, to verify the sex of Roseate Terns (some of whom form homosexual pairs), and to investigate the genetic determinants of mating behavior in different categories of male Ruffs. The extent and characteristics of homosexual pair-bonding in Silver Gulls and Bottlenose Dolphins have been revealed by long-term demographic studies that identified and marked large numbers of individuals, who were then monitored over extended periods. Because most sexual activity in Red Foxes takes place at night, investigators only discovered same-sex mounting in this species by setting up infrared, remote-control video cameras that automatically recorded the animals' nocturnal activities (night photography was also required to document similar activity in wild Spotted Hyenas). Radio tracking (biotelemetry) of individual Grizzlies revealed the activities of bonded female pairs, while similar techniques applied to Red Foxes yielded information about their dispersal patterns and overall social organization that relate to the occurrence of same-sex mounting. Videography, including "frame-by-frame" analysis of taped behavioral sequences, has been utilized in the study of courtship interactions in Griffon Vultures and Victoria's Riflebirds, as well as of communicative interactions during Bonobo sexual encounters (both same-sex and opposite-sex). One ornithologist even x-rayed the eggs belonging to a homosexual pair of Black-winged Stilts to see if they were fertile (they weren't).7

Unfortunately, in a few cases scientists have subjected animals to more extreme experimental treatments, procedures, or "interventions." During several studies of captive animals, same-sex partners in Rhesus Macaques, Bottlenose Dolphins, Cheetahs, Long-eared Hedgehogs, and Black-headed Gulls (among others) were forcibly separated, either because their activities were considered "unhealthy," or in order to study their reaction and subsequent behavior on being reunited, or to try to coerce the animals to mate heterosexually. A female pair of Orange-fronted Parakeets was forcibly removed from their nest — which they had successfully defended against a heterosexual pair — in order to "allow" the opposite-sex pair to breed in their stead (based in part on the mistaken assumption that female pairs are unable to be parents). Female Stumptail Macaques had electrodes implanted in their uteri in order to monitor their orgasmic responses during homosexual encounters, while female Squirrel Monkeys were deafened to monitor the effect on vocalizations made during homosexual activities.

Although intended ostensibly to reveal important behavioral and developmental effects, the "treatments" applied to animals have in some cases been disturbingly similar to those administered to homosexual people in an attempt to "cure" them (separation or removal of partners, hormone therapy, castration, lobotomy, and electroshock, among others). Numerous primates, rodents, and hoofed mammals, {87}

for example, have been subjected to hormone injections to see how this might affect their homosexual behavior or intersexuality. Macaques were castrated as part of behavioral studies that included investigations of homosexual activity, as were White-tailed Deer to determine the "cause" of transgender in this species. Cats have even been lobotomized in order to study the effect on their (homo)sexuality. In some cases, biologists have gone so far as to kill individuals participating in same-sex activities (e.g., Common Garter Snakes, Hooded Warblers, Gentoo Penguins) in order to take samples of their internal reproductive organs.8 The reasons for this — usually to verify their sex or to determine the condition of their reproductive systems, including the presence of any "abnormalities" — reveal the incredulity as well as the often distorted preconceptions that many scientists harbor about homosexuality. As we will see in the next sections, these attitudes often carry over into the "interpretation" or "explanation" of homosexuality/transgender as well.

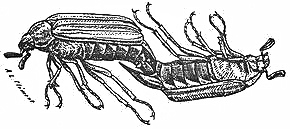

A drawing from 1896 showing two male Scarab Beetles copulating with each other. This is one of the first scientific illustrations of animal homosexuality to be published.

"A Lowering of Moral Standards Among Butterflies": Homophobia in Zoology

... I have talked with several (anonymous at their request) primatologists who have told me that they have observed both male and female homosexual behavior during field studies. They seemed reluctant to publish their data, however, either because they feared homophobic reactions ("my colleagues might think that I am gay") or because they lacked a framework for analysis ("I don't know what it means"). If anthropologists and primatologists are to gain a complete understanding of primate sexuality, they must cease allowing the folk model (with its accompanying homophobia) to guide what they see and report.

— primatologist LINDA WOLFE, 19919

There is an astounding amount and variety of scientific information on animal homosexuality — yet most of it is inaccessible even to biologists, much less to the general public. What has managed to appear in print is often hidden away in obscure journals and unpublished dissertations, or buried even further under outdated value judgments and cryptic terminology. Most of this information, however, simply remains unpublished, the result of a general climate of ignorance, disinterest, and even fear and hostility surrounding discussion of homosexuality that exists to this day — not only in primatology (as Linda Wolfe describes), but throughout the field of zoology. Equally disconcerting, popular works on animals routinely omit any mention of homosexuality, even when the authors are clearly aware that such information is available in the original scientific material. As a result, most people don't realize the full extent to which homosexuality permeates the natural world.

Scientists are human beings with human flaws, living in a particular culture at a particular time. Although the profession demands standards of "objectivity" and nonjudgmental attitudes, a survey of the history of science shows that this has not always been the case. For example, the sexism of much biological thinking has been {88}

exposed by a number of feminist biologists over the past two decades.10 They have shown that not only are scientists fallible human beings, but most are men — and their scientific theorizing has often been (and in many cases continues to be) detrimentally colored by their own and their culture's (often negative) attitudes toward women. This observation can be taken a step further: scientists (who are often heterosexual) frequently project, consciously or unconsciously, society's negative attitudes toward homosexuality onto their subject matter. As a result, both scientific and popular understanding of the subject have suffered.11

There are notable exceptions, of course. A number of scientists have presented relatively value-neutral descriptions of same-sex activity in various species without feeling a need to overlay their own commentary on the behavior, and several authors have recognized that homosexual activity is a "natural" or routine component of the behavioral repertoire in certain animals. Zoologist Anne Innis Dagg, for example, offered a groundbreaking survey of the phenomenon among mammals in 1984 that was light-years ahead of her contemporaries, while the more recent work of primatologist Paul L. Vasey is beginning to directly address some of the inadequacies and biases of previous studies.12 Aside from these few examples, though, the history of the scientific study of animal homosexuality has been — and continues to be — a nearly unending stream of preconceived ideas, negative "interpretations" or rationalizations, inadequate representations and omissions, and even overt distaste or revulsion toward homosexuality — in short, homophobia.13 Moreover, not until the 1990s did zoologists begin to address such biased attitudes: Paul Vasey and Linda Wolfe are, so far, the only scientists to acknowledge in print that there may be a problem in their profession (and Wolfe the only one to name this specifically as homophobia). The full extent, history, and ramifications of the problem, however, have not been previously discussed or documented.

The Perversion of Scientific Discourse

From a distance this might be mistaken for fighting, but perverted sexuality is the real keynote ... . In fact, the birds seem sometimes hardly to understand themselves, or to know where their feelings are leading them ... . My principal observation during the earlier part of the time ... was a repetition of what I have before noted in regard to the sexual perversion, as one calls it — a term which serves to save one the trouble of thinking ... .

— from a scientific description of Ruffs in 1906

Three unnatural tending bonds were observed: ... On July 16 a two-year-old bull closely tended a yearling bull for at least four hours in the Wichita Refuge and attempted mounting with penis unsheathed ... .

— from a scientific description of American Bison in 1958

Among aberrant sexual behaviors, anoestrous does were very occasionally seen to mount one another ... .

— from a scientific description of Waterbuck in 198214

{89}

In many ways, the treatment of animal homosexuality in the scientific discourse has closely paralleled the discussion of human homosexuality in society at large. Homosexuality in both animals and people has been considered, at various times, to be a pathological condition; a social aberration; an "immoral," "sinful," or "criminal" perversion; an artificial product of confinement or the unavailability of the opposite sex; a reversal or "inversion" of heterosexual "roles"; a "phase" that younger animals go through on the path to heterosexuality; an imperfect imitation of heterosexuality; an exceptional but unimportant activity; a useless and puzzling curiosity; and a functional behavior that "stimulates" or "contributes to" heterosexuality. In many other respects, however, the outright hostility toward animal homosexuality has transcended all historical trends. One need only look at the litany of derogatory terms, which have remained essentially constant from the late 1800s to the present day, used to describe this behavior: words such as strange, bizarre, perverse, aberrant, deviant, abnormal, anomalous, and unnatural have all been used routinely in "objective" scientific descriptions of the phenomenon and continue to be used (one of the most recent examples is from 1997). In addition, heterosexual behavior is consistently defined in numerous scientific accounts as "normal" in contrast to homosexual activity.15

The entire history of ideas about, and attitudes toward, homosexuality is encapsulated in the titles of zoological articles (or book chapters) on the subject through the ages: "Sexual Perversion in Male Beetles" (1896), "Sexual Inversion in Animals" (1908), "Disturbances of the Sexual Sense [in Baboons]" (1922), "Pseudomale Behavior in a Female Bengalee [a domesticated finch]" (1957), "Aberrant Sexual Behavior in the South African Ostrich" (1972), "Abnormal Sexual Behavior of Confined Female Hemichienus auritus syriacus [Long-eared Hedgehogs]" (1981), "Pseudocopulation in Nature in a Unisexual Whiptail Lizard" (1991).16 The prize, though, surely has to go to W. J. Tennent, who in 1987 published an article entitled "A Note on the Apparent Lowering of Moral Standards in the Lepidoptera." In this unintentionally revealing report, the author describes the homosexual mating of Mazarine Blue butterflies in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco. The entomologist's behavioral observations, however, are prefaced with a lament: "It is a sad sign of our times that the National newspapers are all too often packed with the lurid details of declining moral standards and of horrific sexual offences committed by our fellow Homo sapiens; perhaps it is also a sign of the times that the entomological literature appears of late to be heading in a similar direction."17 Declining moral standards — in butterflies?! Remember, these are descriptions by scientists in respected scholarly publications of phenomena occurring in nature!

In addition to such labels as unnatural, abnormal, and perverse, a variety of other negative (or less than impartial) designations have also been employed in the scientific literature. Once again, these span the decades. Mounting among Domestic Bulls is characterized as a "male homosexual vice" (1983), echoing a description from nearly a century earlier in which same-sex activities between male Elephants are classified as "vices" and "crimes of sexuality" that are "prohibited by the rules of at least one Christian denomination" (1892). Courtship and mounting between male Lions is called an "atypical sexual fixation" (1942); same-sex relations in {90}

Buff-breasted Sandpipers are described in an article on "sexual nonsense" in this species (1989); while courtship and mounting between female Domestic Turkeys are referred to as "defects in sexual behavior" (1955). Homosexual activities in Spinner Dolphins (1984), Killer Whales (1992), Caribou (1974), and Adelie Penguins (1998) are characterized as "inappropriate" (or as being directed toward "inappropriate" partners), and same-sex courtship among Black-billed Magpies (1979) and Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock (1985) is called "misdirected." In what is perhaps the most oblique designation, one scientist uses the term heteroclite (meaning "irregular" or "deviant") to refer to Sage Grouse engaging in homosexual courtship or copulations (1942).18

Besides labeling same-sex behavior with derogatory or biased terms, many scientists have felt the need to embellish their descriptions of homosexuality with other sorts of value judgments. Repeatedly referring to same-sex activity in female Long-eared Hedgehogs as "abnormal," for example, one zoologist matter-of-factly reported that he separated the two females he was studying for fear that they might actually "suffer damage" from continuing to engage in this behavior. Similarly, in describing pairs of female Eastern Gray Kangaroos, another scientist suggested that only in cases where there was no (overt) homosexual behavior between the females could bonding be considered to represent a "positive relationship between the two animals." In the 1930s, homosexual pairing in Black-crowned Night Herons was labeled a "real danger," while one biologist (upon learning the true sex of the birds) referred to his discovery and reporting of same-sex activities in King Penguins as "regrettable disclosures" and "damaging admissions" about "disturbing" activities. More than 50 years later, a scientist suggested that homosexual behavior between male Gorillas in zoos would be "disturbing to the public" were it not for the fact that people would be unable to distinguish it from "normal heterosexual mating behavior." Same-sex pairing in Lorikeets has been described as an "unfortunate" occurrence, while mounting activity between female Red Foxes has been characterized as being part of a "Rabelaisian mood." Finally, in describing the behavior of Greenshanks, an ornithologist used unabashedly florid and sympathetic language to characterize an episode of heterosexual copulation, referring to it as a "lovely act of mating" and concluding, "The grace, movement, and passion of this mating had created a poem of ecstasy and delight." In contrast, homosexual copulations in the same species were given only cursory descriptions, and one episode was even characterized as a "bizarre affair."19

In a direct carryover from attitudes toward human homosexuality, same-sex activity is routinely described as being "forced" on other animals when there is no evidence that it is, and a whole range of "distressful" emotions are projected onto the individual who experiences such "unwanted advances."20 One scientist surmises that Mountain Sheep rams "deem it an insult to be treated as a female" (including being mounted by another male), while Rhesus Macaques and Laughing Gulls are described as "submitting" to homosexual mounts even when there is clear evidence that they are willing participants (for example, by initiating the activity). Cattle Egrets who are mounted during homosexual copulations are characterized as "suffering males," while female Sage Grouse mounted by other females are their "victims." {91}

Orang-utan males who participate in homosexuality are said to be "forced into nonconformist sexual behavior" by their partners even though they display none of the obvious signs of distress (such as screaming and struggling violently) that are characteristic of female Orangs during heterosexual rapes. Scientists describing same-sex courtship in Kob antelopes imply that females try to "avoid" homosexual attentions by circling around the other female or butting her on the shoulder. In fact, these actions are a formally recognized ritual behavior called mating-circling that is a routine part of heterosexual courtships, and not indicative of disinterest or "unwillingness" on the part of the courted female. Females who do not want to be mounted (by male partners) actually drop their hindquarters to the ground (a behavior not observed in homosexual contexts). Same-sex courtship in Ostriches is deemed to be a "nuisance" that goes "on and on" and is perpetrated by "sexually aberrant" males. The calm stance of a courted male (referred to as the "normal" partner) in the face of such homosexual advances is described as "astonishing," while the recipient's occasional acknowledgment of the activity is downplayed in favor of those times when he makes no visible response (interpreted as disinterest). Yearling male Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock are consistently described as "taking advantage of" or "victimizing" adult males that they mount, while their partners are said to "tolerate" such homosexual activity. This is at odds with the descriptions, by the same scientists, of the adult partners as willing participants who actively facilitate genital contact during homosexual mounts and allow the yearlings to remain on their territories (unlike unwanted adult intruders who are chased away or attacked). Finally, male Mallard Ducks that switch from heterosexual to homosexual pairings are described as being "seduced" by other males, while Rhesus Macaques are characterized as reacting with a sort of "homosexual panic" to same-sex advances — both echoing widely held misconceptions about human homosexuality.21

In other cases, zoologists have problematized homosexual activity or imputed an inherent inadequacy, instability, or incompetence to same-sex relations, when the supporting evidence for this is scanty or questionable at best and nonexistent at worst. For example, the fact that male homosexual pairs in Greylag Geese engage in higher rates of pair-bonding and courtship behavior is ascribed to an (unsubstantiated) "instability" of same-sex pair-bonds. In fact gander pairs in this species have been documented as lasting for 15 or more years and are described as being, in many cases, more strongly bonded than heterosexual mates.22 Similarly, even though pair-bonds between male Ocellated Antbirds can last for years, one ornithologist insisted on portraying them as "fragile" and liable to dissolve at the mere appearance of a "nubile female." Antbird same-sex pairs do sometimes divorce, but so do heterosexual ones, and any generalizations about the comparative stability of each cannot be made without comprehensive, long-term studies of pair-bonding — which have yet to be undertaken for this species.23 The fact that sexual activity between female Gorillas generally takes longer than heterosexual copulations is speculatively attributed to "mechanical difficulties" involved in sex between two females — it is apparently inconceivable to the investigator that females might be experiencing closer bonding or greater enjoyment with each other (as reflected by their face-to-face position and other features that also distinguish homosexual {92}

from heterosexual activity in this species). In the same vein, accounts of same-sex mounting in Western Gulls, Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock, and Red Foxes refer to the "disoriented," "bumbling," or "fumbling" actions of some individuals — terms that are rarely used to describe nonstandard mounting attempts in heterosexual contexts (even when they are equally "incompetent"). Conversely, one primatologist is willing to concede that affiliative gestures (such as mutual touching, grooming, or preening) between animals of the opposite sex may be "tender" and even "an expression of love and affection," yet similar or identical activities between same-sex participants are never characterized this way.24

This double standard is particularly apparent where descriptions of same-sex pairs in Gulls are concerned. When a male Laughing Gull in a homosexual pair courted and mounted a female, for example, this was taken by one investigator to mean that his pair-bond was unstable and that he was "dissatisfied" with his homosexual partnership (rather than as simply an instance of bisexual behavior). In contrast, homosexual activity by birds in heterosexual pairs is never interpreted as "dissatisfaction" with heterosexuality or as reflecting the tenuousness of opposite-sex bonds. In a study on pair-bonding in Black-headed Gulls, the term "monogamous" (implying stability) was reserved for heterosexual pairs, even though homosexual pairs in this species can also be stable and monogamous, and heterosexual pairs are sometimes nonmonogamous. Likewise, the stability of female pairs of Herring Gulls was claimed to be lower than heterosexual pairs. Yet in making this assessment, researchers were considering females to have broken their pair-bond if they were simply not seen at the nesting colony the following year — when in fact they or their partner could have died, relocated, or been missed by observers. Among those females that were subsequently observed at the colony (a more accurate measure, and the standard way of calculating mate fidelity for heterosexual pairs), the rate of pair stability was in fact nearly identical to that of opposite-sex pairs.

Similarly, the parenting abilities of female pairs in many Gull species are often implied to be substandard because such couples usually hatch fewer chicks than heterosexual pairs. However, calculations of the hatching success of homosexual pairs typically include infertile eggs in the overall count; since many females in same-sex pairs do not mate with males, large numbers of their eggs are infertile and so of course a larger proportion of their clutches do not hatch. In addition, all of the traits taken to indicate poor quality of parenting in some female pairs — e.g., smaller eggs, slower embryonic development, lower hatching rate of fertile eggs, reduced weight and greater mortality of chicks, higher rates of loss or abandonment — are also characteristic of supernormal clutches attended by heterosexual parents (usually polygamous trios). In other words, they are related to the larger-than-average clutch size rather than the sex of the parents per se. In fact, most studies of Gulls have shown that the parenting abilities of homosexual pairs are at least as good as those of heterosexual pairs. Moreover, heterosexual parents in many Gull species can be severely neglectful or overtly violent toward their chicks, causing youngsters to "run away" from their own families and be adopted by others (or even perish). Needless to say, this behavior is never interpreted as being representative {93}

of all heterosexual pairs or as impugning heterosexuality in general (even though it is usually far more widespread than homosexual inadequacies).25 Thus, many zoological studies evidence the same inconsistency often found in discussions of human homosexuality: any difficulties or irregularities in same-sex relations are generalized to all homosexual interactions (or else focused on to the exclusion of other examples), whereas comparable problems in opposite-sex relations are seen in the proper perspective, simply for what they are — individual (or idiosyncratic) occurrences that, while noteworthy, do not reflect the entirety of heterosexuality nor warrant disproportionate attention.

Homophobia in the field of zoology is not always this overt or virulent; nevertheless, ignorance or negative attitudes that are not directly expressed usually have identifiable consequences and important ramifications for the way the subject is handled. Discussion of animal homosexuality has in fact been compromised and stifled in the scientific discourse in four principal ways: presumption of heterosexuality, terminological denials of homosexual activity, inadequate or inconsistent coverage, and omission or suppression of information.

Heterosexual Until Proven Guilty

... after about twenty minutes I realized that what I was watching was three whales involved in most erotic activities! ... Then one, two, and eventually three penes appeared as the three whales rolled at the same time. Obviously, all three were males! It was almost two hours after the first sighting ... and up to that point I was convinced I was watching mating behavior. A discovery — and a stern reminder that first impressions are deceiving.

— JAMES DARLING, "The Vancouver Island Gray Whales"26

Many behavioral studies of animals operate under a presumption of heterosexuality: a widespread — if not universal — assumption among field biologists is that all courtship and mating activity is heterosexual unless proven otherwise. This is particularly prevalent in studies of animals in which males and females are not visually distinguishable at a distance. The scientific literature is filled with examples of biologists who were convinced that the sexual, courtship, or pair-bonding activity they had been observing was between a male and female — until confronted with {94}

clear evidence of homosexuality, such as a glimpse of two sets of male genitalia, or a nest containing more eggs than just one female could have laid.27

Moreover, many zoologists still routinely determine the sex of animals in the field based on their behavior during sexual activity — with the (often unstated) assumption that there must be both a male (the one doing the mounting) and a female (the one being mounted) in any such interaction. Of course, this automatically eliminates any "chance" of observing homosexual activity in the first place. A field study of Laughing Gulls, for example, utilized the following assumptions in determining the sex of birds: "(1) any bird copulating more than twice on top was presumed a male, and (2) the mate of a male was presumed to be a female." Yet other studies of this species in both the wild and captivity have revealed that male homosexual mounting and pairing do in fact occur in Laughing Gulls. Scientists studying sexual behavior in Common Murres admitted that they probably underestimated the frequency of homosexual mounting because they assumed that sexual activity involved opposite-sex partners unless they had direct evidence to the contrary. Amazingly, this practice is even used in species where homosexual behavior is known to occur from previous studies of either captive or wild animals, such as Kittiwakes and Griffon Vultures.28 True, some biologists have critiqued this method of sex determination — but only on the grounds that it can miss examples of reverse heterosexual mounting (where females mount males).29 And in spite of its obvious shortcomings, behavioral sex determination continues to be employed in recent studies, some of which constitute the first and only documentation of little-known species. One can only guess at how many examples of homosexual activity have been and will continue to be overlooked because of this.30

Even in captivity, the sex of animals is often mistaken, and the consequent "amending" of mating or courtship activity from heterosexual to homosexual sometimes results in elaborate retractions, revisions, and reinterpretations. Renowned German ornithologist Oskar Heinroth, for example, published one of the first descriptions of heterosexual mating in Emus — only to discover that the two birds he had been observing in captivity were in fact both males, prompting him to publish a "correction" to his earlier description three years later. In reviewing the earliest descriptions of courtship behavior in captive Regent Bowerbirds, scientists realized that what had previously been described as heterosexual activity was in fact display behavior performed between two males. This resulted in rather confusing citations of the earlier material such as the following, in which the true sex of the birds is indicated by the later author's bracketed insertions (prefaced by the assertion "I make no apology for revising in brackets his text to make it meaningful"): "'These love-parlours, each one built by a female [immature male] for her [his] sole use ... were of the shape of a horseshoe ... . The female would enter and squat in her [in the immature male's] love-parlour, the tail remaining towards the entrance ... the rejected females [immature males in adult female dress] ... built or partly built three love-parlours in different spots.'" The very first description of "heterosexual" courtship and mating in Dugongs (a marine mammal) was published, ironically, in a scientific article prefaced with lines of romantic verse about the "heaving bosoms" of mermaids and sea nymphs (creatures that the animal has historically been {95}

mistaken for). Ironic, because nearly a decade later biologists confirmed that both animals involved in this sexual activity were actually males.31

Perhaps the most convoluted — and humorous — mix-up of this sort involves a set of King Penguins that were studied at the Edinburgh Zoo from 1915 to 1930. The various permutations and shufflings of mistaken gender identities (on the part of human observers, not the birds) reached truly Shakespearean complexity. The sex of the penguins was initially determined on the basis of what was thought to be heterosexual behavior, and the birds were given (human) names accordingly. Following this, however, some "puzzling" observations of apparently homosexual activity were made. Subsequent re-pairings and breeding activity eventually revealed — more than seven years later! — that in fact the sex of all but one of the birds had been misidentified by the scientists. At this point a comprehensive "sex change" in the names of the birds was hastily instituted to reflect their true genders: "Andrew" was renamed Ann, "Bertha" turned into Bertrand, "Caroline" became Charles, and "Eric" metamorphosed into Erica ("Dora" had correctly been identified as a female). Ironically, although some previous "homosexual" interactions could be reclassified as heterosexual once the true sex of the birds was known, other less straightforward revisions were also required. Two penguins that had initially been seen engaging in "heterosexual" activity — "Eric" and Dora — later turned out to be same-sexed, while premature observations of lesbian mating between "Bertha" and "Caroline" were confirmed as homosexual — but actually involved the males Bertrand and Charles!32

Sometimes the presumption of heterosexuality concerns not the sex of animals but the context in which courtship or pairing activity occurs. This can be characterized as a "heterocentric" view of animal behavior, i.e., one that tends to see all forms of social interaction as revolving around heterosexual activity (see chapter 5). For example, female homosexual pairs in a number of birds, such as Snow Geese, Ring-billed Gulls, Red-backed Shrikes, and Blue Tits, were initially thought to represent the female portion of heterosexual trios. The females were erroneously assumed to be bonded not to each other but to a third, male, bird (that had yet to be observed) — to the extent that several researchers felt compelled to provide explicit evidence and argumentation that no male was associated with such female pairs. Likewise, courtship and mounting activity between male Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock was categorized as a form of "disruption" of heterosexual courtships in one study, when in fact the majority of same-sex activity took place outside of heterosexual courtships when females weren't even around. In a similar vein, same-sex behavior in Stumptail Macaques was classified as sexual in one study only if it occurred "during or immediately after or between heterosexual copulations." In summarizing the pairing strategies adopted by widowed Jackdaws, one scientist enumerated only heterosexual mating patterns and failed to include the formation of female homosexual pairs, even though his own data showed that 10 percent of widowed females attracted new female mates. Likewise, one author's discussion of homosexual activity in male Cheetahs focused on a single case where males mounted each other in apparent "frustration" during heterosexual courtship activities, when in fact the majority of same-sex interactions did not occur in this type {96}

of context. Finally, sexual activity and bonding between female Bonobos has traditionally been interpreted as a derivative extension of heterosexuality and subsumed under the general patterns of male-female relations. Recent work, however, shows that female bonding and homosexuality in this species are in fact autonomous from heterosexuality, not geared toward attracting opposite-sex partners, and actually much stronger and more primary than male-female bonding.33

Similar assumptions have frequently guided the treatment of actual sexual behavior, most blatantly when same-sex activity is excluded entirely from the definition of what constitutes sexual activity. One researcher, for example, only considered cases involving "insertion of the penis into the vagina" to be genuine examples of sexual penetration in Savanna (Olive) Baboons, and a study of Right Whales classified behavior as sexual only if it occurred in groups containing both males and females. A recent study of Moose defined sexual mounting behavior solely as "a male mounting a female," while any mounting activity in Cattle Egrets "in which male-female cloacal [genital] contact appeared to be impossible" was classified a priori as "incomplete" or unsuccessful sexual activity.34 Anal and oral intercourse are not the only forms of penetration excluded by these sorts of definitions. In discussing homosexual activity in female Squirrel Monkeys, one scientist bluntly asserted that clitoral penetration — the insertion of one female's clitoris into another's vagina — was anatomically impossible: "Because of the structure of the female genitalia, however, intromission between females is not possible." In fact, the clitoris in Squirrel Monkeys and many other female mammals becomes conspicuously erect during sexual arousal, and actual clitoral penetration has been documented during lesbian sexual activity in Bonobos, and it may also occur in Spotted Hyenas.35 The phallocentric viewpoint expressed in comments such as these is merely the most recent manifestation of attitudes that can be traced back to some of the earliest descriptions of animal homosexuality. In 1922, for example, one scientist wrote of female homosexual interactions in Savanna (Chacma) Baboons, "The physical completion of the act was, of course, impossible and it seemed more like an impulsive action in which there was no real sexual excitement involved."36 This perfectly epitomizes the sort of stereotypes and misinformation that have continued to engulf homosexuality to this day, in both animals and people.

Mock Courtships and Sham Matings

The attitude that homosexual activity is not "genuine" sexual, courtship, or pair-bonding behavior is also sometimes made explicit in the descriptions and terminology used by researchers. In spite of witnessing two male homosexual mounts during a morning spent observing Ruffs, for example, one ornithologist reported offhandedly that "there were no real copulations" because no heterosexual mounting took place; a similar comment was made by a scientist studying Bonnet Macaques.37 This attitude is also encoded directly in the words used for homosexual behaviors: rarely do animals of the same sex ever simply "copulate" or "court" or "mate" with one another (as do animals of the opposite sex). Instead, male Walruses indulge in "mock courtship" with each other, male African Elephants and {97}

Gorillas have "sham matings," while female Sage Grouse and male Hanuman Langurs and Common Chimpanzees engage in "pseudo-matings." Musk-oxen participate in "mock copulations," Mallard Ducks of the same sex form "pseudo-pairs" with each other, and Blue-bellied Rollers have "fake" sexual activity. Male Lions engage in "feigned coitus" with one another, male Orang-utans and Savanna Baboons take part in "pseudo-sexual" mountings and other behaviors, while Mule Deer and Hammerheads exhibit "false mounting." Bonobos, Japanese and Rhesus Macaques, Red Foxes, and Squirrels all perform "pseudo-copulations" with animals of the same sex.38 Amid this abundance of counterfeit sexual activity, one thing is all too real: the level of denial on the part of some zoologists in dealing with this subject.39

Even use of the term homosexual is controversial. Although the majority of scientific sources on same-sex activity classify the behavior explicitly as "homosexual" — and a handful even use the more loaded terms gay or lesbian40 — many scientists are nevertheless loath to apply this term to any animal behavior. In fact, a whole "avoidance" vocabulary of alternate, and putatively more "neutral," words has come into use. "Male-male" or "female-female" activity is the most common appellation, although some more oblique designations have also appeared, such as "male-only social interactions" in Killer Whales or "multifemale associations" for same-sex pairs in Roseate Terns and some Gulls. Homosexual activities are also called "unisexual," "isosexual," "intrasexual," or "ambisexual" (meaning single-sex, same-sex, within-sex, and bisexual, respectively) in various species such as Gorillas, Ruffs, Stumptail Macaques, Hooded Warblers, and Rhesus Macaques. The use of "alternate" words such as unisexual is sometimes advocated precisely because of the homophobia evoked by the term homosexual: one scientist reports that an article on animal behavior containing homosexual in its title was widely received with a "lurid snicker" by biologists, many of whom never got beyond the "sensationalistic wording" of the title to actually read its contents.41

Occasionally there are directly opposing assertions regarding the suitability of the term homosexual for the same behavior and species. In a relatively enlightened treatment of same-sex activities in Giraffes, for example, one zoologist stated, "Such usage [of the term homosexual] is acceptable provided it is used without the usual human connotation of stigma and sexual abnormality ... . In giraffes the erection of the penis, mounting, and even possibly orgasm leaves little doubt as to the sexual motivation behind these actions." In contrast, a decade later another zoologist objected, "Considerable significance has been attached to the fact that necking males sometimes show penis erections and that one may mount the other ... such behavior has been called 'homosexual.' However ... I ... do not feel that the use of the term homosexual, with its usual (human) connotation, is justified in this context."42 Ironically, where the first scientist objected only to the stigma associated with the term as applied to people, the second objected to the connotation of genuinely sexual behavior in the term as applied to people.

When it comes to heterosexual activities, however, scientists are not at all adverse to making analogies with human behaviors. Opposite-sex courtship-feeding in birds is described as "romantic" and reminiscent of human lovers kissing, male canaries whose vocalizations attract female partners are said to sing "sexy" songs, while avian {98}

heterosexual monogamy and foster-parenting are compared to similar activities in people (in spite of the acknowledged differences in the behaviors involved). Even more flagrant anthropomorphizing sometimes occurs: male-female interactions in Savanna Baboons, for example, are likened to "May-December romances," "flirting," and other human courtship rituals in a "singles bar"; polyandry in Tasmanian Native Hens is termed "wife-sharing"; opposite-sex bonds between cranes who readily pair with one another are characterized as "magic marriages"; and heterosexually precocious male Bonobos are dubbed "little Don Juans." Female fireflies that lure males of other species by courting and then eating them are labeled "femmes fatales," and one scientist even uses the term gang-bang to describe group courtship and forced heterosexual activity in Domestic Goats. Regardless of whether these characterizations are appropriate, among zoologists it is still more acceptable (in practice if not in theory) to draw human analogies where heterosexuality is concerned.43

Many scientists' denial that same-sex courtship, sexual, pair-bonding, and/or parenting activities should be put in the category of "homosexuality" are based on spurious or overly restrictive interpretations of the phenomenon (or the word). For example, Konrad Lorenz claims that gander pairs in Greylag Geese are not actually "homosexual" because sexual behavior is not necessarily an important component of such associations (not all members of gander pairs engage in sexual activity), and because not all such birds pair exclusively with other males over their entire lifetime. By the same criteria, however, opposite-sex pairs would fail to qualify as "heterosexual": sexual activity is not an important component of male-female pairings in this species (as Lorenz himself acknowledges), and not all such birds pair exclusively with opposite-sex partners during their lives. Yet Lorenz has no qualms about labeling such pairs "heterosexual."44 In fact, what we have here is simply an attempt to equate homosexuality with only one characteristic or type of same-sex activity (sexual versus pair-bonding, or sequential bisexuality versus exclusive homosexuality).

In a parallel discussion of female pairs in Western Gulls, one researcher suggests that previous descriptions of such pairs as "homosexual" or "lesbian" or "gay" is inappropriate because they do not resemble homosexual pairings in humans.45 But which homosexual pairings, in which humans? As discussed in chapter 2, there is no single type of same-sex pair-bonding in people: homosexual couples differ vastly in a wide range of factors such as their sexual behavior, social status, formation process, sexual orientation of members, participation in parenting, duration, and so on, and they vary enormously between different cultures, historical periods, and individuals. Assuming, however, that this author is referring to Euro-American lesbian couples, it is difficult to see what specific similarities are required before the label of homosexual would be considered acceptable. Same-sex pairs in both Gulls and humans engage in a variety of courtship, pair-bonding, sexual, and parenting activities and exhibit parallel variability in their formation, social status, and the sexual orientation of their partners. In fact, it is fallacious to suggest that a same-sex activity should resemble some human behavior before we can label it homosexual. A more reasonable approach (the one used in this book as well as in many scientific sources) is to take comparable behaviors in the same or closely related species as the {99}

point of reference: any activity between two animals of the same sex that involves behaviors independently recognized (usually in heterosexual contexts) as courtship, sexual, pair-bonding, or parenting activities is classified as "homosexual." By this criterion, same-sex pairs of Gulls are "homosexual" because all of the characteristics they exhibit are well-established components of pair-bonding in heterosexual pairs of the same species — to the extent that same-sex couples have often been mistaken for heterosexual ones and unhesitatingly labeled a "mated pair" before their true sex was discovered.

More generally, a number of scientists have suggested that the term homosexual should be reserved for overt sexual behavior, and that it is inappropriate to apply this word to other behavior categories such as same-sex courtship, pair-bonding, or parenting arrangements. We might characterize this as a "narrow" definition of homosexuality (such as that assumed by Lorenz). On the other hand, homosexuality, as the term is used in this book, refers not only to overt sexual behavior between animals of the same sex, but also to related activities that are more typically associated with a heterosexual or breeding context. This usage is consistent with a number of studies in the zoological literature, in which the word is employed as a cover term for both sexual and related behaviors (e.g., courtship, pairing, parenting).46 We might characterize this as a "broad" definition of homosexuality. Although overt sexual behavior is by far the single most common type of same-sex activity found in various species — hence the original terminology — the other behavior categories also occur in a sizable proportion of cases in which same-sex activities have been documented. In many (but not all) species, behaviors of various categories co-occur (e.g., sexual and courtship activity with pair-bonding, courtship or bonding with parenting, and so on). There are also numerous cases where only one behavior type is instantiated, or where several behavior categories co-occur in the same species but are not necessarily observed in the same individuals (e.g., sexual behavior may be seen between some animals, courtship behavior between others, etc.). In some cases this represents actual discontinuities of behaviors; in others, it represents observational gaps. When the term homosexuality is employed in the broad sense for these cases, it is always with the understanding that only selected behavior categories or co-occurrences may be involved (as in observations of heterosexual behavior).47

The difference between these two usages of the term homosexual can be illustrated with an example involving two different forms of same-sex activity (each widely attested in birds, sometimes both in the same species). On one hand, consider two female birds that are pair-bonded to each other for life, regularly engage in courtship activity with one another, build a nest each year in which they jointly lay eggs, and on one occasion raise chicks together (fathered via a single heterosexual copulation that season by one of the partners), yet never mount each other. On the other hand, consider a male bird who is mated to a female partner for life — with whom he regularly copulates and raises offspring — but who participates in a single copulation with another male (and never again engages in such behavior for the remainder of his life). A narrow definition of homosexuality would require us to consider the first case to be somehow less "homosexual" than the second simply {100}

because no overt sexual behavior takes place between the two females. A broad view of homosexuality, on the other hand, recognizes that both cases involve homosexual behavior — but of two distinct types that need to be carefully distinguished in terms of their social context as well as the other sexual and pairing activities of the participants (since both scenarios actually exemplify contrasting forms of bisexuality). Unlike the narrow definition, this usage acknowledges the complexities and variability of same-sex interactions in the animal world, while providing a useful framework for cross-species comparisons and generalizations; it also offers the possibility of more precise and nuanced characterizations of sexual orientation.

Most scientists are understandably wary of anthropomorphizing animals with terms that have wide applicability in a human context — as well they should be — and obviously not all zoologists who avoid the word homosexual are motivated by homophobia. Nevertheless, the lengths that are taken to circumvent terminology that can easily be clarified with a simple explanatory statement often border on the absurd.48

"Not Included in the Tabulated Statistics"

Even when homosexual behavior is recognized as such, detailed study of it is often omitted or passed over, or the phenomenon is marginalized and trivialized. For instance, numerous published reports on the courtship and copulation behavior of animals provide excruciatingly detailed descriptions and statistics on frequency of mounts, number of ejaculations, duration of penile erections, number of thrusts, timing of estrous cycles, total number of sexual partners, and so on and so forth — but all for heterosexual interactions. In contrast, homosexual activity is often mentioned only in passing, not deemed worthy of the exhaustive coverage that is afforded "real" sexual behavior.49 In a detailed study of Spinner Dolphin sexual activity, for example, only heterosexual behavior is quantified and given a thorough statistical treatment, even though the author recognizes the prominence of homosexual activity in this species and actually states directly that its frequency exceeds that of heterosexual behavior. Another study of the same species mentions homosexual copulations without providing the total number observed, unlike heterosexual matings. In a tabulation of homosexual and heterosexual activity in Kob antelopes, the number of male partners of each female is cataloged while the number of female partners is not. Likewise, articles on Crested Black Macaque and Brown Capuchin sexual behavior acknowledge the occurrence of female homosexual activity yet offer no statistics on this behavior, even though it is said to be more common (in Crested Blacks) than male homosexual activity (which, along with heterosexual behavior, is quantified). Finally, graphs of the frequency of various Giraffe activities in one study fail to provide adequate information on homosexual mounts: all same-sex interactions are lumped into the category of "sparring" (a form of fighting) without distinguishing actual sparring from necking (a ritualized, nonviolent form of play-fighting and affection) or mounting activity.50

Sometimes certain aspects of homosexual activity are excluded or arbitrarily eliminated from an overall analysis or tabulation — often resulting in a distorted picture of same-sex interactions (regardless of whether the omission is deliberate {101}

or well-motivated). For instance, a female Western Gull who exhibited the most overt sexual activity with her female partner was "not included in the tabulated statistics" of a study comparing heterosexual and homosexual behaviors. By failing to incorporate data from this individual (intentionally or not), researchers undoubtedly helped foster the (now widely cited) impression that sexual activity is a uniformly negligible aspect of female pairing in this species. Along the same lines, scientists surveying pair formation in Black-crowned Night Herons only tabulated homosexual couples that they considered to be "caused" by the "crowded" conditions of captivity. They ignored a male pair whose formation could not be attributed to such conditions and also overlooked the fact that such "crowded" conditions regularly occur in wild colonies of the same species. And all data concerning same-sex pairs or coparents in Laughing Gulls, Canary-winged Parakeets, Greater Rheas, and Zebra Finches were excluded from general studies of pair-bonding, nesting, or other behaviors in these species.51

The significance of homosexual activity is sometimes also downplayed in discussions of its prevalence or frequency. Certainly many variables must be considered when trying to quantify same-sex activity, and the task is rarely straightforward (as we saw in chapter 1). Nevertheless, in some instances homosexual frequency is interpreted or calculated so as to give the impression that same-sex activity is less common than it really is or else is de-emphasized in terms of its importance relative to other species. In Gorillas, for example, homosexual activity in females is classified as "rare" because investigators observed it "only" 10 times on eight separate days. However, these figures are incomplete unless compared with the frequency of heterosexual interactions during the same period. In fact, 98 episodes of heterosexual mating were recorded during the same period, which means that 9 percent of all sexual activity was homosexual — a significant percentage when compared to other species.52 Similarly, investigators studying lesbian pairs in Western Gulls state, "We have estimated female-female pairs make up only 10-15 percent of the population" (emphasis added), when in fact this is one of the higher rates recorded for homosexual pairs in any bird species (and certainly the highest rate reported at that time). Homosexual mounting in female Spotted Hyenas is claimed to be much less frequent than in other female mammals, yet no specific figures are offered; the one species that is mentioned in comparison is the Guinea Pig, a domesticated rodent that is not necessarily the best model for a wild carnivore.53

It is also important to consider the behavioral type and context when evaluating frequency. Homosexual copulations in Tree Swallows, for example, have been characterized as "exceedingly rare" because they have been observed only infrequently and are much less common than heterosexual matings between pair-bonded birds. However, homosexual copulations are nonmonogamous matings (i.e., they typically involve birds that are not paired to one another and may even have heterosexual mates); it is insufficient in this case to compare the frequency rates of two different kinds of copulation (within-pair and extra-pair). In fact, the more comparable heterosexual behavior — nonmonogamous copulations involving males and females — are also "rarely" seen. Early observers considered them to be exceedingly uncommon (or nonexistent), while a later study documented only two {102}

such matings during four years of observation, and subsequent research has yielded consistently low levels of observed promiscuous (heterosexual) copulations. Yet scientists now know that such matings must be common because of the high rates of offspring resulting from them — in some populations, more than three-quarters of all nestlings (as verified by DNA testing). Thus, it is likely that the frequency of homosexual nonmonogamous matings has been similarly underestimated.54

Many scientists, on first observing an episode of homosexual activity, are also quick to classify the behavior as an exceptional or isolated occurrence for that species. In contrast, a single observed instance of heterosexuality is routinely interpreted as representative of a recurrent behavior pattern, even though it may occur (or be observed) extremely rarely or exhibit wide variation in form or context. This sets up a double standard in assessing and interpreting the prevalence of each behavior type, especially since opposite-sex mating can be a less than ubiquitous or uniform feature of an animal's social life (see chapter 5). It also conflicts with the patterns established for other species. In repeated instances, homosexual activity was initially recorded in only one episode, dyad, or population (and usually interpreted — or dismissed — as an isolated example), but was then confirmed by subsequent research as a regular feature of the behavioral repertoire of the species — often spanning many decades, geographic areas, and behavioral contexts. 55 It is no longer possible to claim that homosexuality is an anomalous occurrence in a certain species simply because it has only been observed a handful of times.

In some cases, conflicting verbal assessments of the prevalence of homosexual activity are offered by the same investigators, when the actual quantitative data show a relatively high occurrence. Homosexual courtship/copulation in Pukeko, for example, is described as being both "common" and "relatively rare" — the actual rate of 7 percent of all sexual activity is in fact fairly high compared to other species (and the same-sex courtship rates are even higher). Likewise, a report on Black-headed Gulls states, "Homosexual pairs were also rare," then a few pages later counterasserts that "male-male bonds occurred rather commonly" — and at approximately 16 percent of all pairs observed, the actual rates support the latter interpretation more than the former.56 Not only are these assessments inconsistent and unfair with regard to the observed rates of homosexuality, they also run counter to a standard cross-species measure of heterosexual frequency. Although there is no absolute or universal criterion for what is "rare" or "common," biologists do recognize a "threshold" of 5 percent as being significant where at least one heterosexual behavior is concerned — polygamy. When this mating system is exhibited by only a minority of the population (as is true in many birds, for example), it is nevertheless considered to be a "regular" feature of the species' behavioral repertoire when its incidence reaches 5 percent. This is certainly far less than the rate of homosexuality in many species where same-sex behavior is regarded as "uncommon" or "exceptional."57

In a vivid example of the marginalization that often surrounds discussion of animal homosexuality, scientists sometimes find their own descriptions of same-sex activity published with "amendments," "asides," or "explanations" inserted by {103}

journal or reprint editors who are uncomfortable with the content or appellation. For example, one ornithologist's description of homosexual activity in House Sparrows and Brown-headed Cowbirds was embellished with a note from the editor of the journal where it appeared, offering several implausible "reinterpretations" of the behavior that eliminated any sexual motivation. Likewise, when descriptions of homosexual activity in Baboons from the 1920s were reprinted nearly half a century later, a scientist who penned the introduction to the new edition felt compelled to annotate the offending passages with the "modern" viewpoint that such activity is not really homosexual. And editors of the journal British Birds scrambled to try to "explain" a case of homosexual pairing in male Kestrels as actually involving a "male-plumaged female" (i.e., a female bird that looked exactly like a male). They added in their published postscript to the article that this putative plumage variation was, in their opinion, "of much more interest than the copulation or attempted one between the two males" that was the primary focus of the author's report.58

In a similar vein, one scientist who observed a pair of female Chaffinches hedged his bets by saying only that "female-plumaged" birds were involved, leaving open the possibility that one might still have been a male (and consequently part of a heterosexual pair) — even though there was absolutely no evidence that either bird could have been a male. He finally had to concede that the birds "were surely females." Sometimes this strategy backfires, as in the case of an early description of courtship display in Regent Bowerbirds (mentioned previously), in which the presumed "female-plumaged" birds both turned out to be males — and therefore still participants in homosexual activities.59 These cases show that scientists are sometimes reluctant even to commit to the sex of the animals they are observing if it seems that homosexuality might be involved — in stark contrast to the haste with which they usually judge (or assume) participants to be opposite-sexed on the scantiest of evidence.

The Love That Dare Not Bark Its Name

Although the first reports of homosexual behavior among primates were published >75 years ago, virtually every major introductory text in primatology fails to even mention its existence.

— primatologist PAUL L. VASEY, 199560

In the 1890s, Oscar Wilde's lover, Lord Alfred Douglas, characterized homosexuality as "the Love that dare not speak its name," referring to the silence and stigma surrounding disclosure of homosexual interests and discussion of same-sex activities. 61 An analogue to this silencing and stigmatization exists in the pages of zoology journals, monographs, and textbooks, and in the wider scientific discourse. Discussion of homosexual activity in animals has frequently been stifled or eliminated, and a number of examples can only be considered active suppression of information on the subject. When several comprehensive reference works devoted to every conceivable aspect of an animal's biology and behavior are published, including {104}

chapters by scientists who originally observed homosexuality in the species, and yet consistently no mention is made of that homosexual behavior, one has to wonder about the "objectivity" of these scientific endeavors.

At one extreme, there are cases of apparently deliberate removal of information. In 1979, a report on Killer Whale behavior was issued by the Moclips Cetological Society, a nonprofit scientific organization devoted to whale study. Sexual activity between males — classified explicitly as "homosexuality" in the report — was discussed at some length, concluding with the statement, "Homosexual behavior has been observed in many animals including cetaceans, canids, and primates, and, in some cases, it has significance for social order." A year later, when this report was published as a government document for the U.S. Marine Mammal Commission, all mention of homosexuality was eliminated even though the remainder of the report was intact.62 At the other extreme are cases where homosexuality is discussed but is buried in unpublished dissertations, obscure technical reports, foreign-language journals, or in articles whose titles give no clue as to their content. For example, the earliest reports of same-sex courtship and mounting in wild Musk-oxen appeared in an unpublished master's thesis at the University of Alaska and a (published) report for the Canadian Wildlife Service. Consequently, a study on homosexual activity in captive Musk-oxen conducted more than 20 years after the initial discovery fails to mention any occurrence of this behavior in the wild. Similarly, the first reports of Walrus homosexual activity, complete with photographs, were published in an article with the rather opaque title of "Walrus Ethology I: The Social Role of Tusks and Applications of Multidimensional Scaling," while all records of homosexual behavior in Harbor Seals are contained in unpublished reports and conference proceedings that are only available at a handful of libraries in the world. This perhaps explains why virtually every subsequent discussion of homosexuality in animals omits any mention of these two species.63

Between these extremes are numerous examples where homosexuality is "overlooked" or fails to gain mention. Describing itself as "the culmination of years of intensive research and writing by more than 70 authors" — all experts on the species — the massive book White-tailed Deer: Ecology and Management (1984) presents in minute detail every imaginable aspect of this animal's biology and behavior, no matter how obscure or rare. There's even room in the book's nearly 900 pages for lengthy discussion of "abnormal" and pathological phenomena (a category in which homosexual activity is often placed). Although the chapter on behavior was coauthored by the scientist who originally described homosexual mounting in White-tailed Deer, there is no mention anywhere in the book of this particular behavior. Nor is there discussion of the transgendered deer found in Texas, even though a whole chapter is devoted to this regional population. A decade later, the same scenario was repeated when another volume of the same scope and on the same species was put out by the same publishers. Similarly, a standard scientific source book, The Gray Whale, Eschrichtius robustus (1984), omits any reference to homosexuality in this species even though it includes a chapter by the first biologist to record same-sex activity in Gray Whales.64 Several comprehensive reference volumes on woodpeckers fail to mention homosexual copulations in {105}

Black-rumped Flamebacks, even though no other (hetero)sexual behavior has ever been observed in this species. This omission cannot be due to the putative rarity or "insignificance" of such behavior, since one book does mention another behavior that has only ever been observed once in wild woodpeckers — bathing.65 Other in-depth surveys of individual species follow suit, eliminating any mention of homosexuality even when they make direct use of other information from the very sources that describe same-sex activity.66

Because of the omission and inaccessibility of information on animal homosexuality in the scientific literature, many zoologists are themselves unaware of the full extent of the phenomenon. One of the most unfortunate consequences of this is that misinformation (and absence of information) about the subject is widely disseminated and perpetuated from one source to the next. On discovering homosexual activity in a particular species they are studying firsthand — and being unable to find more than a handful of comparable examples in a cursory literature search — many zoologists acquire the mistaken impression that their observations of this behavior are somehow unique or unusual. At that point they may issue blanket statements to the effect that homosexual activity is rare or previously unreported in the form or species they are observing. Such statements are then often repeated by other biologists and become definitive pronouncements on the subject. As recently as 1993, for example, a scientist reporting on Hooded Warblers could claim that male homosexual pairs had not previously been seen in wild birds — when, in fact, such pairs were documented more than a quarter century earlier in Antbirds, Orange-fronted Parakeets, Golden Plovers, and Mallard Ducks, and thereafter in Black Swans, Scottish Crossbills, Black-billed Magpies, and Pied Kingfishers, among others.67 Scientists studying same-sex pairs of Black-headed Gulls in captivity asserted in 1985 that this behavior had yet to be seen in this species in the wild — apparently unaware of a description of a male homosexual pair in wild Black-headed Gulls published in a Russian zoology journal just a year earlier. And researchers who discovered same-sex matings in Adelie and Humboldt Penguins and in Kestrels stated that they did not know of any comparable phenomena in other species of penguins or birds of prey, when in fact homosexual activity in King Penguins, Gentoo Penguins, and Griffon Vultures had previously been reported in the literature.68

Sadly, omission and misinformation on the subject of animal homosexuality have ramifications far beyond the individual scientific articles in which they occur. Reference works such as those mentioned above are frequently consulted by researchers in other fields, and they are also the source of much of the information on animal behavior that is presented to the general public. As the quote at the beginning of this subsection indicates, the cycle is also perpetuated through each new generation of scientists as the textbooks they use (or the professors who instruct them) continue to offer inaccurate or incomplete information on the subject (when they aren't completely silent on the topic). It is no surprise, then, that many scientists — and, by extension, most nonscientists — continue to harbor the erroneous impression that homosexuality does not exist in animals or is at best an isolated and anomalous phenomenon. When erasure and silence surround the subject {106}

among zoologists, misinformation and prejudice readily fill in the gaps — both in the scientific community and beyond.

To conclude this examination of homophobic attitudes in the scientific establishment, one simple observation can be made: given the considerable obstacles encountered in the recording, analysis, and discussion of the subject, it is remarkable that any descriptions of animal homosexuality make it to the pages of scientific journals and monographs (or to a wider audience). A great deal of progress is being made, and the situation today is certainly improved over that of even a decade ago. Moreover, none of this discourse would even be possible without the invaluable work of zoologists and wildlife biologists who study animals firsthand and report their findings — however flawed that study and reporting may be at times. Nevertheless, the examples of animal homosexuality currently contained in the zoological literature represent only the tip of the iceberg. Many more remain to be discovered, recorded, and granted the scientific attention that has so repeatedly been denied them in the past.

Anything but Sex

As we have seen, one way that zoologists have tried to avoid classifying same-sex activity as "homosexuality" is by using terminology and behavioral categories that deny it is sexual activity at all. This approach also extends to the interpretations, explanations, and "functions" attributed to same-sex behavior, even when it involves the most overt and explicit of activities. Astounding as it sounds, a number of scientists have actually argued that when a female Bonobo wraps her legs around another female, rubbing her own clitoris against her partner's while emitting screams of enjoyment, this is actually "greeting" behavior, or "appeasement" behavior, or "reassurance" behavior, or "reconciliation" behavior, or "tension-regulation" behavior, or "social bonding" behavior, or "food exchange" behavior — almost anything, it seems, besides pleasurable sexual behavior. 69 Similar "interpretations" have been proposed for many other species (involving both males and females), allowing scientists to claim that these animals do not really engage in "genuine" (i.e., purely sexual) homosexual activity. But what heterosexual activity is ever "purely" sexual?

{107}

Most biologists are not as candid as Valerius Geist, who, in Mountain Sheep and Man in the Northern Wilds, readily admits to his discomfort and homophobia in trying to "explain" homosexuality in Bighorn Rams as "aggressive" or "dominance" behavior:

«I still cringe at the memory of seeing old D-ram mount S-ram repeatedly ... . True to form, and incapable of absorbing this realization at once, I called these actions of the rams aggressosexual behavior, for to state that the males had evolved a homosexual society was emotionally beyond me. To conceive of those magnificent beasts as "queers" — Oh God! I argued for two years that, in [wild mountain] sheep, aggressive and sexual behavior could not be separated ... . I never published that drivel and am glad of it ... . Eventually I called the spade a spade and admitted that rams lived in essentially a homosexual society.»70