The Naked Child Growing Up Without Shame

<< Chapter VIII >>

Family Ties: The Importance of Place

Sally Mann

One of the things my career as an artist might say to young artists is the things that are close to you are the things that you can photograph the best. And unless you photograph what you love, you're not gonna make good art. I've nothing but respect for people who travel the world to make art, who put exotic Indians in front oflinen backdrops. But it's always been my philosophy to try and make art out of the everyday and ordinary. It never occurred to me to leave home to make art.

William Carlos Williams is one of my favorite poets. And he makes the point that it's all about what he calls the “local”. He actually makes it a noun, and he's right. For me, the local has two parts: my family and the land. They give me comfort in times of failure and, of course, they're the wellspring and inspiration for all my work..

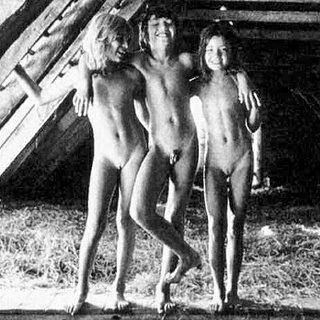

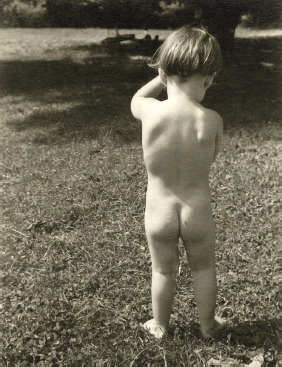

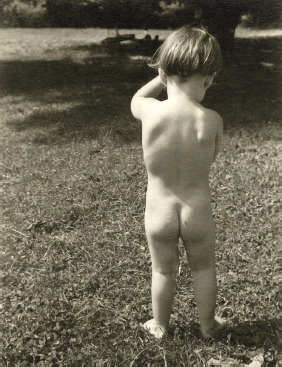

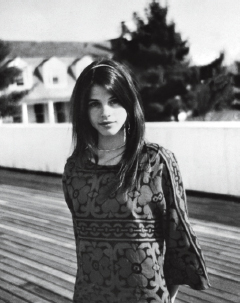

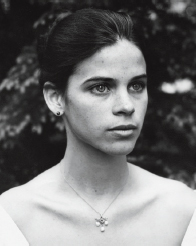

I photographed my family and my children in particular. I have seldom shied away from photographing what was performing and as a consequence many of the pictures are intimate and revelatory. The purpose was to take a picture of something that is in every family, and in every childhood memory, you know, it happens. Every mother in the world has seen this picture countless times, and I guess, I was just documenting something that was true, it was an absolute when it came to parenting and being a child. There are many pictures in which my children are nude or hurt or sick or angry. The children are participants who have been since infancy enveloped in my creative process. We are spinning a story based on fact but embracing fiction of what it is to grow up. I have until now told it without fear and without shame. But increasingly I am uncertain as to the ultimate consequences of this work.

I went back and tried to remember how I felt when I took the first pictures. I mean I was photographing in a vacuum there wasn't any of this controversy. So I was taking pictures of, you know, what was going on around me which involved a measure of nudity and it never ever occurred to me that I would get in trouble for them. It must sound like I'm speaking with a measure of guile but I'm not, it never occurred to me. On the other hand it may just be that the country has gotten more conservative in the 5-10 years I've been doing this.

I think a lot of these pictures show that people find so appealing is an utterly unspoiled kind of life where the children are allowed to be completely natural. I think that's pretty rare. And in American society obviously it's very rare because people's reactions, it's real clear, that they're surprised by these pictures and surprised by the the degree of freedom that the children are allowed to have, I guess, particularly in terms of their own dress.

Virginia: «There has never really been a time that my mom has told me to take off clothes. I at most pictures have been without clothes or have been willing to go without clothes and have had my mom asked me to put on clothes. I like to go without clothes and it's quite comfortable.»

So these pictures reflect that lifestyle. And to me it seems perfectly natural. I'd have to be an artist in a straitjacket not to take these pictures. It seems perfectly natural to do it. And that's why I'm a little nonplussed sometimes when people respond with, you know, at the nudity in a picture like that when that's really what she was doing at that exact moment, she was leaning up against a tree in a sunset.

No creative need, no monetary gain and no First Amendment rights supersede my responsibilities to my children. As an artist, I defend to the death my right to take and show these pictures, and yet as a mother I must ask myself if self-inflicted censorship would be in the children's best interests. Children derive their values and their strength from their parents. For me, to show ambivalence would be a capitulation and a form of treason. It is time for us to stand behind a lifestyle and a system of values that is strong and rare in its cohesiveness. And time to defend our right to live in such a way that these photographs can be taken. and fight for an artistic climate that allows them to be shown without fear.

I can't float these little pictures out in the world like so many little boats on a rough sea and then go charging after them saying, wait a minute, wait a minute, it was okay, it's just fine, she's not really hurt, or, you know, I didn't make her take her clothes off, or... I mean, I can't chase after these pictures and with apologies all the time. At some point you really have to ask yourself, this sort of Rosa Parks' question, you know, will I stand up or will I sit down in my seat in the bus.

The place is important; the time is summer. It’s any summer, but the place is home and the people here are my family.

I have lived all my life in southwestern Virginia, the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. And all my life many things have been the same. When we stop by to see Virginia Carter, for whom our youngest daughter is named, we rock on her cool blue porch. The men who walk by tip their hats, the women flap their hands languidly in our direction. Or at the cabin: the rain comes to break the heat, fog obscuring the arborvitae on the cliffs across the river. Some time ago I found a glass-plate negative picturing the cliffs in the 1800s. I printed it and held it up against the present reality, and the trees and caves and stains on the rock are identical. Even the deadwood, held in place by tenacious vines, has not slipped down.

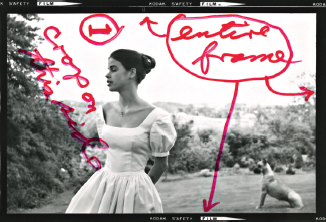

And the clothes: the Easter dress was made for me when I was six by my mother and her mother, Jessie Adams. When Jessie Mann, thirty years later, spreads out that skirt, the hills that surround her are the same modest ones of our home.

I remember the heat. My mother, a Bostonian, would retreat to her bedroom for the afternoon, tendrils of long black hair stuck to her neck. I’d stay out with Virginia, sitting in her great lap as she peeled the apples, a dozen fat boxers lazing at our feet. The year my parents went to Europe, Virginia took me to her church. All the women wore white gloves and worked their flowered fans. I stood when Virginia stood, and great waves of music rolled over me. They tumbled me like a pale piece of ocean glass, and I washed up outside, blinking in the sudden heat and sunshine of Main Street.

Ninety-three years separate the two Virginias, my daughter and the big woman who raised me. The dark, powerful arms are shrunken now, even as the tight skin of my daughter’s arms puckers with abundance. But, still, it seems that time effects slow change here. At the cabin, the river’s course is as invariable as the habits of its denizens: the great blue heron, who flies so fearlessly close that we can hear old gristle grind in his wing joints; the beaver; the eerie albino carp, almost fluorescent in the night water. In the fields above the river, cattle graze, turning toward us with those same dull faces, white like town children. And, across the county, my mother still lives in the same house, and the children roll in the new-mown grass down the same long hill. But my father is dead.

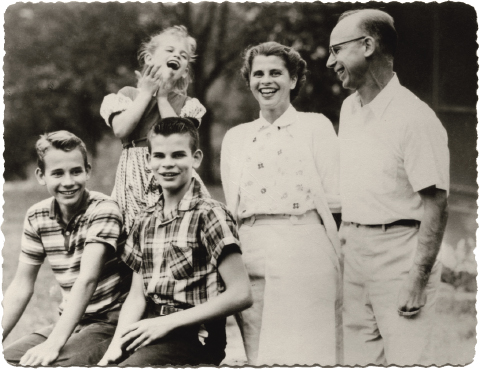

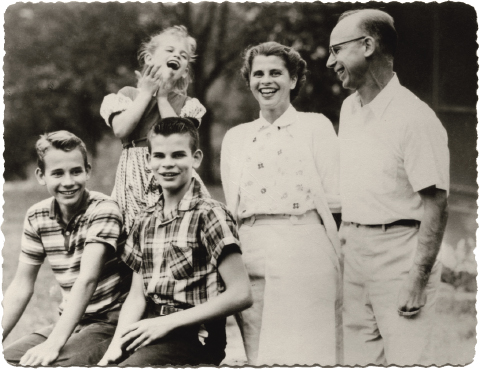

It was my father who gave me almost all my cameras, the first half-dozen, I guess. He was an atheist who practiced compassionate medicine, 60 hours a week. He was enough of a socialist to believe you shouldn't have to pay for it if you couldn't. But he was also an art collector, I mean, he bought Kandinsky in the '30s, and Twombly in the '50s. And he was quite an unusual man, and hell to live up to. But then, of course, my mother... In all different kinds of poses here. You couldn't have two more disparate backgrounds. My mother with this, like, blue-blood New England, and my father sort of a renegade Texan.

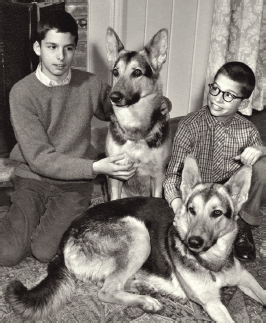

But I was the third child. Two older brothers... And I sort of think by the time I came along, everyone was tired of raising children. It wasn't that they neglected me, it was a benign neglect, I guess. I know I never wore clothes. They're all, every picture of me is naked. And they had 12 boxers, so I was always surrounded by a pack of dogs. I just ran wild for the first seven years of my life — and then went to school, and didn't take to it too kindly, but I was eventually civilized. I guess that's a little how I raised my own kids. And a little why I was so nonplussed when people were so surprised to see the pictures of my children without shirts and pants, and running wild, too. It seemed like a perfectly normal thing to do, to me.

His garden ... how to talk about it: thirty acres with giant oaks, ponds in the lowlands, and hillsides of orchard. It was wilderness when he bought it in 1950. I remember the grim energy with which he worked, ripping out the devil’s shoestring, stripped to the waist and sweating in the heat. As he cleared each acre, he planted trees he had purchased in England, the Orient — the rarest of the rare. He was a man possessed.

But the land was still wild when I grew up, a feral child running naked with the pack of boxers. The sound of the axe, the tractor, Daddy’s Indian call brought us back, panting and scratched from crawling through the tunnels we had made in the mounded honeysuckle. I was an Indian, a cliff-dweller, a green spirit; I rode my horse with only a string through his mouth, imagining flight.

The Sight of My Eye

Until my early twenties, I kept handwritten journals. As I filled each one, I would pile it on top of the others under my desk and discard the bottom one. The first to go, I remember, was a small, pink child’s journal with “My Precious Thoughts” in cursive gold lettering on the cover, those thoughts safeguarded by a pitifully ineffectual brass lock.

When I was eighteen, in the winter prior to my June wedding, I relinquished my room to my mother, who had huffily left her marital bed when Tara, a Great Dane, moved into it with my father. Cleaning out my stuff, I pulled out the journals accumulated so far and bundled them into a box I labeled “Journals, 1968–.”

Ripping the desiccated masking tape off that box some forty years later, I wasn’t surprised to find that the first entry in the earliest journal was a paean to the formative Virginia landscape of my youth. It begins:

«It has been a mild summer, with more rain than most. We work hard and grow tired. The evening is cool as we watch the night slide in and hear each sound in the still blue hour. The silver poplar shimmers and every so often the pond ripples with fish. The mountains grow deep. They are darker than the night.»

Judging by the unembellished declarative sentences in those first paragraphs, it’s a safe bet I was reading Hemingway that summer, somewhere around my seventeenth. But read down a few more lines and I come over all Faulknerian, soaring into rhapsodic description:

«We reach the top pasture and you are ahead and spread your arms wide. I run to catch up and it opens to me. There is no word for this; nothing can contain it or give it address. There are no boundaries, no states. The mountains are long and forever and they give the names, they give the belief in the names. The mountains give the name of blue, the name of change and mist and hour and light and noise of wind, they are the name of my name, the hand of my hand and the sight of my eye.»

I have loved Rockbridge County, Virginia, surely since the moment my birth-bleary eyes caught sight of it. Not only is it abundant with the kind of obvious, everyday beauty that even a mewling babe can appreciate, but it also boasts the world-class drama of the Natural Bridge of Virginia, surveyed by George Washington and long vaunted (incorrectly, as it turned out) on local billboards as one of the Seven Natural Wonders of the World. Like any true native, I didn’t bother to investigate our local tourist draw until well into my thirties, and when I did I was chagrined, blown away by its airy audacity.

After checking out the Natural Bridge, visitors looking for a dose of the Ye Olde will usually make a stop in history-rich Lexington, the county seat (pop. 7,000), where I grew up. Plenty of interesting people have been born or passed time in Lexington, the artist Cy Twombly being among the more notable, but also Cyrus McCormick, inventor of the reaper; Gen. George Marshall; Tom Wolfe; Arnold Toynbee; Alben Barkley, vice president under Truman, who not only passed through here but passed away here, being declared dead on the dais in midspeech by my own physician father; and Patsy Cline, who lived just down the creek from our old house in town.

The young novelist Carson McCullers, burdened by the meteoric success of The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter and recovering in Lexington, was once hauled out of a bathtub at a mutual friend’s house, fully clothed, drenched, and drunk, by my mother. Thinking about it now, it’s probably a good thing that my mother is not around to receive the unwelcome news that her oft-told stories about Edward Albee writing Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? while in Lexington are likely apocryphal. Not only that, but she said he did so in a cottage on the grounds of my childhood home, Boxerwood, while visiting its occupant James Boatwright. I’m pretty sure her assertion that the Albee characters George and Martha had been based on a local faculty couple famous for their bickering and alcohol consumption is incorrect, too, but that probably wouldn’t stop her even now from deliciously persevering with it. Besides, it’s still believable to me, for I well remember the sounds of the drinking and bickering during Boatwright’s late-night literary parties at the cottage drifting down to my open bedroom windows during the early sixties.

The eye-filling Reynolds Price visited Boatwright often (as did, at various times, Eudora Welty, Mary McCarthy, and W. H. Auden), and on the night I attended my first prom at age fourteen, he and Boatwright emerged from the screen porch to drunkenly toast me, calling me Sally Dubonnet, a term I find baffling even today, as their gin rickeys sloshed over the glasses.

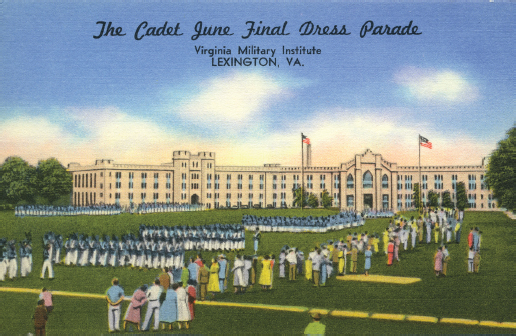

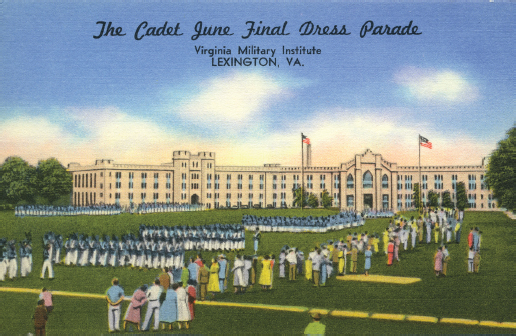

What brings both luminaries and regular visitors to Lexington are often the two handsome old colleges, Washington and Lee University and Virginia Military Institute, which coexist uncomfortably cheek by jowl, as well as the homes and burial places of Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee. The remains of those defeated generals’ horses, Little Sorrel and Traveller, are also here, one at VMI, the other at W&L.

When I was growing up, Traveller’s bleached skeleton was displayed on a plinth in an academic building at W&L, pinned together somewhat worryingly by wire and desecrated with the hastily carved initials of students. Just a few blocks north from Traveller at neighboring VMI, the nearly hairless hide of the deboned Little Sorrel was displayed in the museum. I was told that a local guide once explained to his clutch of credulous tourists that the skeleton was Little Sorrel as a mature horse and the stuffed hide was Little Sorrel when he was just a young colt.

The Shenandoah Valley attracts many visitors; some come for its history, especially its Civil War history, but even more for its undeniable physical beauty. It is said that as the radical abolitionist John Brown stood on the elevated scaffold in his last minutes, he gazed out at our lovely valley in wonderment. Eyewitnesses reported that before the hangman covered his head, John Brown turned to the sheriff and expressed with windy eloquence his admiration for the landscape before him. The sheriff responded laconically but with unambiguous agreement, “Yup, none like it,” and signaled the hangman to pull, pdq, the white hood over Brown’s valley-struck eyes.

John Brown was gazing south from the northernmost, and widest, part of the valley, but had he been standing on the scaffold in our part, some 150 miles south, his wonderment and fustian would have been tenfold. Everyone’s is, even without the scaffold and the imminent hood. Had Brown been in Rockbridge County, he would have begged the hangman for one more minute to experience the geologic comfort of the Blue Ridge and Allegheny mountain ranges as they come together out of the soft blue distance.

This effect is especially apparent as you drive down the valley on I-81, the north-south interstate that parallels I-95 to the east. As you approach Rockbridge, the two mountain ranges begin to converge, forming a modest geographic waist for the buxom valley. By the time you cross the county line, neither of them is more than a ten-minute drive in either direction.

If that weren’t enough extravagant beauty for one medium-sized county, then shortly after crossing into Rockbridge you are presented with the eye-popping sight of three additional mountains: Jump, House, and Hogback. Responding to Paleozoic pressure, this anomalous trio erupted like wayward molars smack in the central palate of the valley, each positioning itself with classical balance, as though negotiating for maximum admiration. When they come into view at mile marker 198.6, occasionally radiant with celestial frippery, you will stomp down on the accelerator in search of the next exit, which happens to be the one for Lexington.

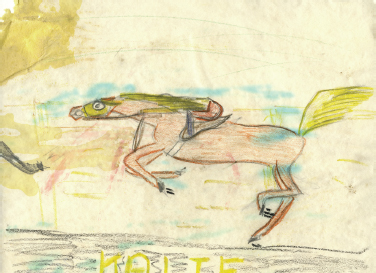

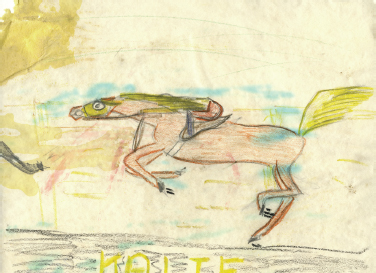

I had the good fortune to be born in that town. In fact, even better, I was born in the austere brick home of Stonewall Jackson himself, which was then the local hospital. Due to overcrowding, I bunked in a bureau drawer (maybe Jackson’s own?) for the first few days of my life. And when I was a stripling I rode my own little sorrel, an Arabian named Khalifa, out across the Rockbridge countryside just as Jackson did. I could ride all day at a light hand gallop through farm after farm, hopping over fences oppressed with honeysuckle and stopping only for water. Much of that landscape is now ruined with development, roadways, and unjumpable fencing, but the mysteries and revelations of this singular place, just as I observed in my earliest journal entries, have been the begetter and breathing animus of my artistic soul.

All the Pretty Horses

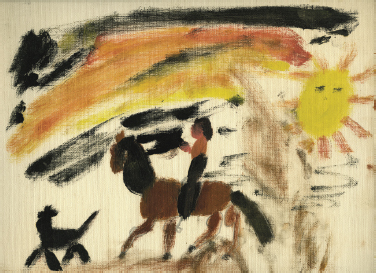

Except for a stretch in the middle of my life, horses have been either a fervent dream, as these childhood drawings attest,

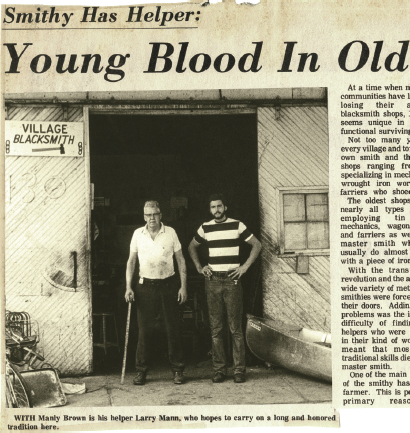

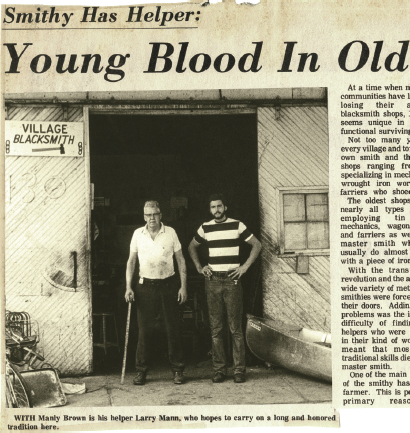

or a happily realized fervent passion. To write about how important place is to me, especially in my life with Larry Mann and in my photographs, I have to address how essential horses have been to it as well. Larry and I had three often cash-strapped decades when we had no horses in our lives, between our marriage in 1970 and our move thirty years later to our farm. But all that time my buried horse-passion lay still rooted within me, an etiolated sprout waiting to break greenly forth at the first opportunity.

And when at last that opportunity came in the spring of 1998 and Larry and I acquired our family farm from my older brothers, Chris and Bob, I bought the first horse I could find. With the purchase of that spavined old (re-)starter mount, my dormant obsession burst into full, extravagant leaf.

~

I’ve been said to be temperamentally drawn to extremes, in good ways and bad, and part of what I love about the kind of riding I do is the extreme physicality of it. Appropriately called “endurance riding,” the sport entails competitions of thirty, fifty, and one hundred miles, going as fast as you safely can and almost exclusively on tough little Arabian horses just like Khalifa.

The landscape through which we race is usually so remote it is just the horse and me for dozens of fast and sometimes treacherous miles, an elemental, mindless fusion of desire and abandon. Sometimes we are running alone in the lead, and at those times I can’t deny the observation of the writer Melissa Pierson that nothing may be fiercer in nature or society than a woman gripped by a passion to win. Nothing, that is, except a mare so possessed.

And in those moments I am wowed by the subtle but unambiguous communication between our two species, a possibility scoffed at by those unfortunates who haven’t experienced it, but as real and intoxicating as the smell of the sweating horse beneath me. That physical and mental bond — the trail ahead framed between my eager horse’s pricked ears, and the ground flying under her pounding hooves — can reset my brain the way nothing else does and, in doing so, lavishly cross-pollinates my artistic life.

This riding rapture, so essential to my mind and body, would never have been possible, and my slumbering horse passion would have remained buried and unrealized, were it not for our farm. And not just that: without the farm, many of the other important things in my life — my marriage to Larry, the family photographs, the southern landscapes — might never have happened either.

On our fortieth wedding anniversary, in June 2010, I received this email from our younger daughter, Virginia:

«Although you have said you don’t want to make a big fuss about this, I think you are both proud of what you have achieved today: it is a testament to love, to a commitment to equality, patience, selflessness and, of course, the farm.»

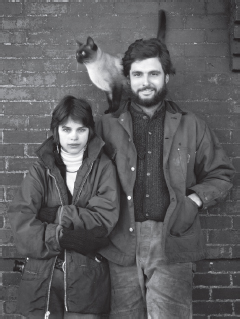

How odd it is that a piece of land should figure so prominently into her concept of our marriage, and yet how perceptive and accurate that observation is. I met Larry when I was 18. A freshman at Bennington. Came home for a Christmas break to see my boyfriend, who was Larry's best friend.

Before Larry and I met, in December 1969, our farm had been the setting for an Arthurian pageant of predestination, set in the aftermath of an epic flood. The flood of 1969 just almost leveled the cabin and in the process of doing so it deposited this huge stone like, five or six feet from the front door of the cabin — just mammoth.

In August 1969, Hurricane Camille rolled into Pass Christian, Mississippi, where she hit with Category 5 intensity, then made her way northeast and crossed the Appalachian Mountains into the Shenandoah Valley. Picking up moisture from heavy rains in the previous days, Camille dumped a staggering twenty-seven inches of rain in three hours onto the mountain streams that drain into the Maury River, the dozy midsized waterway that loops around our farm.

Our cabin on the Maury, built well above any existing flood line, was clobbered by a wall of water carrying logs, parts of buildings, cars, and detritus of every imaginable kind. The water reached the roofline, but a large hickory prevented the cabin from joining its brethren headed a hundred and fifty miles downstream to Richmond. As the flooding diminished, leaving angry snakes, a poignantly solitary baby shoe, tattered clothing, splintered wood, and nearly a foot of sand on its floor, the cabin subsided more or less where it had been before.

My parents wearily began shoveling out the sandy gunk, noting the many treasures washed away by the floodwaters. Most vexing was the loss of the large entry stone, concave like an old bar of soap, that had memorably required several men to put it in place at the cabin’s 1962 christening. Believing such a rock could not have been swept far, my father eventually located it under a mound of debris and shoveled it free. But he needed some help to move it back to the doorway. My father needed some help moving the stone so he called up my then W&L boyfriend C. Turner, and said, “Do you know anyone who could help me lift this stone?” And C. said, “I know just the person.” So he offered to come with his strong friend, Larry Mann, and brought Larry out. The three of them rode out to the farm on a fall afternoon in my father’s green Jeep.

Apparently, the rock’s smooth surface made it difficult to grip and several times it nearly mashed their toes. And C. and my father were trying to lift this stone. After one particularly close call, Larry asked the other two to stand back, “Here, let me do this,” and in a moment I imagine as bathed in a focused beam of mote-flecked sun streaming through the tree canopy, hoisted the rock onto his back.

My father and boyfriend surely stood openmouthed… no, indeed, in my mythically heroic replay, I am sure they knelt, shielding their eyes as they gazed up at the epic vision of luminous Larry Mann replacing the threshold stone.

But in prosaic truth, lusterless Larry reached down and lifted the stone by himself, put it up on his back, staggered to the cabin with the stone barely atop his back, moved it to the front door of the cabin and unceremoniously dumped it, put it down in reasonable proximity to the door, panting with the effort, and turned around and looked at them as if it was effortless for him. Still, even without the imagined heroism, my boyfriend said that when he glanced over at my father he was startled to see him looking at Larry with a bright gleam of acquisitiveness in his eye. Certainly it was more than just satisfaction at having the stone back in place. My boyfriend C. Turner told me that at that moment he knew right then that the result of this portent-laden moment was that Larry Mann would be marrying my father’s daughter and that I was gonna marry Larry Mann. It was like love at first sight. I mean, 33 years later it's hard to conjure it all up, but that's what it was. 'Cause by the time — see, I met him right before Christmas — and by New Year's Eve we decided we were gonna get married.

We get along really well. We just figured everything out from the beginning. We wanted to travel for a certain period of time, but then move back to Lexington. He thought of himself as an artist too. He was doing sculpture. But it sort of devolved to the person who could earn the money as an artist and it turned out to be me — not as an artist, but as a photographer. I was doing sort of the handshake and hand-over-the-check kind of pictures — the swim team, all that stuff. So Larry read the law and after three years he took the bar and he was a lawyer. So we saw things the same way. We had a very similar aesthetic and life dream which, I guess, ultimately played out.

I've taken pictures of Larry from the very beginning. What I'm trying to do in that series that I call — it has a little pet name: Marital Trust — is just do a portrait of a marriage. Everything from the commonplace — you know, working in a garden, cutting the dog's nails, to bathing, to sex, to just everything — all the things that we do in our life together. He's a good sport. Larry's just a really good sport. I mean, imagine the degree of trust that he has to have for me as an artist. I mean, he has to believe that I'm gonna make a good — enough picture to justify putting himself out that way.

In a funny kind of way, I think of this series as an aesthetic savings account. l know they're there, and l know they're good. You know, maybe they'll never come out. Maybe they'll come out after I kick the bucket. But it's a very comforting thought to know that those pictures are in that box in my darkroom.

And here is where the horses come back in. One of the tenuous links that my childhood had with Larry’s was that we both rode and loved horses. Without this link, my father’s marital hopes for his daughter might never have been realized. But, like so much of his childhood, Larry’s riding experience was a world apart from mine.

~

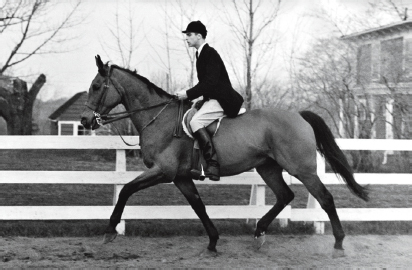

There’s a certain horse culture to which I yearned to belong when I was young — the culture of grooms, bespoke boots, imported horses, boozy hunt breakfasts, scarlet shadbellies, and grouchy, thick-bodied German instructors biting down on their cigars. This was Larry’s horse world.

Mine, more passionate and far less structured, revolved around a Roman-nosed plug and her companion, a bright chestnut Arabian yearling given to my father, a country doctor, in return for a kitchen-table delivery. The former was misnamed Fleet and we named the colt Khalifa Ibn Sina Demoka Zubara Al-Khor, which classed him up a little. There were no grooms to clean the boggy lean-to that housed this unlikely pair, I rode without a helmet in Keds sneakers and untucked blouses with Peter Pan collars, and I never had a real lesson.

At first I didn’t even have a saddle, as my parents assumed that if they made it miserable enough, this “horse-crazy” phase would pass. But I stuck with it, riding that old mare bareback, her withers so high and bony they could serve as a clitoridectomy tool. After six months of this, I decided that the nicely rounded back of the little Arabian colt looked awfully appealing.

So, one day I climbed up on the eighteen-month-old youngster who hadn’t had the first moment of training, and off we rode, a rope halter my only means of control. As one might imagine, Khalifa taught me the only thing I ever really needed to know about riding, and perhaps about life: to stay balanced. Never mind the heels down, the pinky finger outside the rein, or mounting from the left. This little red colt taught me how to ride like a Comanche.

And that’s what we did, flying hell-bent-for-leather across the nearby golf course, which my socialist-minded parents had taught me to disdain, sailing over barbed-wire fences and, when the heat softened the asphalt, racing startled drivers on flat stretches of the road. I rode Khalifa every day and, in a preview of my later miscreant teenage behavior, would set my alarm to ring under the pillow and climb out the window to ride under the wild, fat moon.

My parents, despite my obvious joy in riding, still refused to support it. I understand their indifference, or perhaps it was something stronger — disapproval. They were intellectuals; they hung out with artists and academics, not horse people. The thought of my proper Bostonian, New Yorker–reading mother resting her spectator pump on a muddied rail and chatting up a neatsfoot-oil-smelling horse mother is almost impossible for me to conjure. So antithetic is that notion that even then, when I suffered their indifference most painfully, I didn’t particularly resent it.

It would suit this narrative if I were to tell you that my mean and insensitive parents sent me to boarding school in the snowy north to separate me from my true love, Khalifa. But the truth is this: my confused and concerned parents sent me to the snowy north (that part is still true) because my reckless behavior on horseback had morphed into reckless behavior in other areas. The biggest threat to a young equestrienne is not the forbidden bourbon from the flask on the hunt field or a foot caught in the stirrup of a runaway horse. It is, of course, boys.

My first horse chapter ended badly. When I left for boarding school, my father shuffled Khalifa and Fleet out to the farm where they apparently harried the cattle belonging to a tenant. This cowpoke called our house one night and, with a bumpkin persuasion that could charm a snake into a lawn mower, convinced my father to give the horses to him for riding. Within a week he sent the old mare to be killed at the meat market. When we discovered this, I went in search of my fine little sorrel Khalifa, tracking his dwindling fortunes as he went from one horse trader to the next in Black Beauty–like abasement, before ending up, like the mare, as dog food.

The Bending Arc

As many people have remarked, I am lucky to have found Larry Mann when I did. Whether I was born this way or my personality was formed by circumstance, I don’t think anyone would call me an easy person to deal with, and by the time our paths crossed, the hormones of the teen years had only made things worse.

I had been a near-feral child, raised not by wolves but by the twelve boxer dogs my father kept around Boxerwood, the honeysuckle-strangled and darkly mysterious thirty-acre property where I grew up. The story of my intractability has been told and retold to me all my life by my elders, usually accompanied by a friendly little cheek pinch and a sympathetic glance over at my mother. Recently, in tracking down stories about Virginia Carter, the black woman who worked for my family for nearly fifty years, I visited Jane Alexander, a ninety-six-year-old who repeated to me, in a soft voice with a bobby-pin twang to it, the now familiar tale of my refusal to wear a stitch of clothing until I was five. Family snapshots seem to bear this out.

Elizabeth Munger, Sally's mother: «The first two years ofher life she refused to wear any clothes. And l wouldn't take her to town unless she put on some clothes. Most of the time she said she didn't wanna go to town. She wouldn't make that concession to going to town. She liked being naked. She had temper tantrums and she would hold her breath until she got blue. That was her way of showing her rage 'cause she wasn't getting her way.»

I know that my mother tried to raise me properly, but I made her cross as two sticks, so she turned the day-to-day care of her stroppy, unruly child over to Virginia, known to everyone as Gee-Gee, a name given her by my eldest brother, Bob. Jane Alexander reminded me about the beautiful, often handmade dresses that Gee-Gee would lovingly press for me, in hopes that they would soften my resolve to live as a dog. I have them still, pristine and barely worn.

If my early years sound a bit like those legends of wolf-teat sucklers, I guess they were. But, all the same, when I compare the lives of children today, monitored, protected, medicated, and overscheduled, to my own unsupervised, dirty, boring childhood, I believe I had the better deal. I grew into the person I am today, for better or worse, on those lifeless summer afternoons having doggy adventures that took me far from home, where no one had looked for me or missed me in the least.

Looking back, though, it could be that my parents were a bit on the less-than-diligent side, even for the times. Once, when I was with my mother in the dry-goods section of Leggett’s department store, we saw the distinctive going-to-town hat worn by Mrs. Hinton bobbing above the bolts of cloth. She was the mother of my brother Bob’s best friend, Billy Hinton. When she saw my mother she brightened and said, “Oh, Billy just received a postcard from Bob. Apparently he loves his new school!”

My mother, rubbing some velveteen between forefinger and thumb, responded distractedly, “Oh, that’s good, we hoped he had gotten there okay.”

Turns out that ten days before, my parents had packed a steamer trunk full of warm clothes for my fifteen-year-old brother and driven him to the Lynchburg, Virginia, train station. After eight hours on the Lynchburg train, he had to change stations in New York. My parents told him to carry his trunk from Penn Station to Grand Central and to locate the overnight train to a town near the Putney School, the Vermont boarding school he was to attend. Then they left him and apparently never wondered if those connections had worked for the boy, who had not traveled alone before, or even if he had made it to Putney at all. They had heard nothing since dropping him off and had never called the school to check.

My mother told that story countless times, laughing gaily at her recollection of Mrs. Hinton’s shock.

The assumption back then, in the palmy, postwar Eisenhower years in America, was that everything was fine now — and that was true, for the most part. I think my parents were fairly untroubled by child-rearing issues, except for the constant battles over clothing their stubborn hoyden; my father called me “Jaybird” because I was that naked. But eventually even that was solved by the arrival, in 1956, of Mr. Coffey’s carpentry crew, there to build a cottage for my grandmother Jessie on the property. My mother proposed a deal: if I wanted to hang out with the carpenters, I had to wear clothes of some sort. I was so lonely I took it.

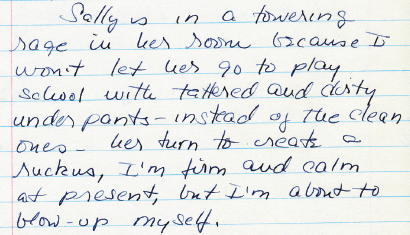

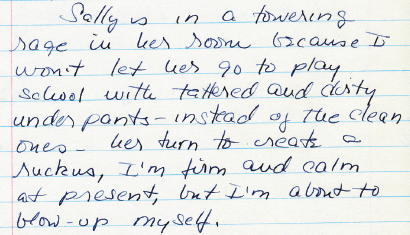

Even though I finally agreed to wear clothing, I had some difficulty working out the details, as my mother’s exasperated journal entries report.

Despite being kicked out several times for not wearing any underwear, never mind tattered and dirty, a few mornings a week I began to attend Mrs. Lackman’s preschool, where I worked on my socialization skills.

When I was about six, my father gave me a book called Art is Everywhere. It was one of those kid's books where it tells you to crawl under the tablecloth of your dining room table and look for the intriguing little crumbs that you find on the floor just to appreciate the quotidian. And I guess I must have taken it to heart 'cause I've never forgotten the book and the concept is as valid to me now as it was then..

By springtime, I had managed to make some human friends whose parents drove them out to my house for a birthday party presided over by Gee-Gee.

By the time I began real school, I was almost normal: I no longer spent my days poking at snapping turtles in the pond, or hiding out with my grubby blanket in my honeysuckle caves, or following my unneutered beagle on his amorous adventures down the paved road, from which, when I was hungry, I would pull stringy hot tar to chew like gum.

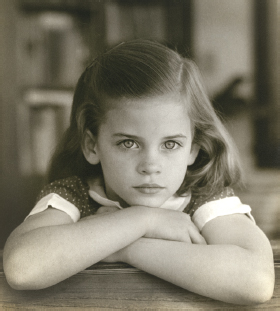

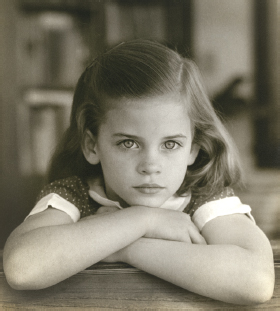

I now wore crinolines, little white socks, and gauzy dresses.

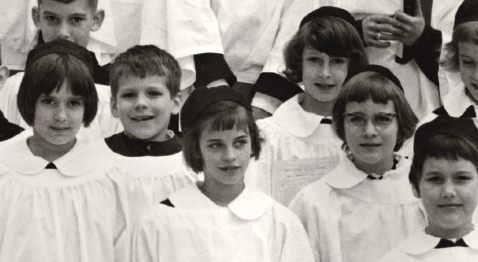

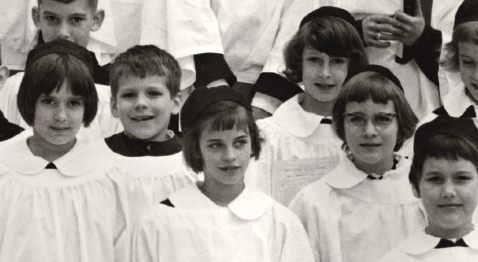

I joined the Brownies

and the Episcopal Church choir.

But look closely: if you study the choir picture, something is still not quite tamed in the child pictured there.

And what is this? What is in those Brownie eyes?

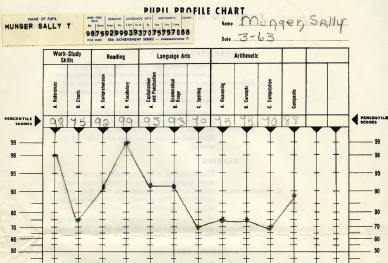

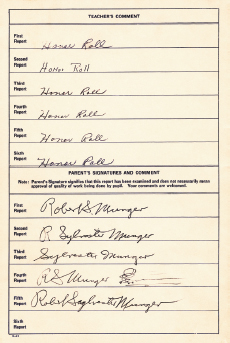

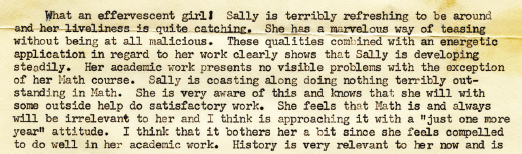

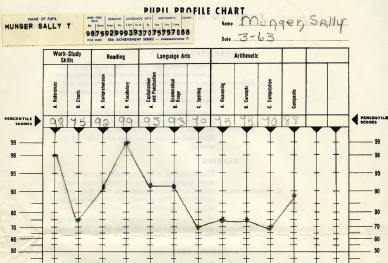

If you had to judge by my average test scores, I suppose it’s not raw intelligence you see in them. I was always a pretty bad test taker, especially so where math was concerned.

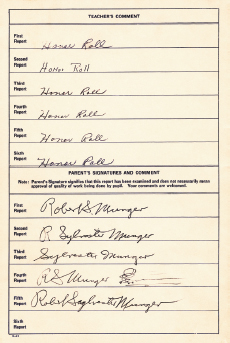

Still, I had enough gray matter in the brainpan and was a diligent and hard worker once I got fired up. As I went through school I discovered I was also competitive, on the honor roll all the way until high school:

(Note my father’s whimsically varied signatures. I lined up eight years of report cards, all signed by him, and all signed in a different way. He was a busy man, a practicing medical doctor: how did he manage to keep this silly conceit going?)

In those years and the horse years that followed (the pre–driver’s license years), I had as halcyon a life as any rural girl, despite the obstacles my horse-insensitive parents placed in my way. My natural, unquenchable rebellious streak played out on horseback, and, as I am still engaging in irresponsible, high-speed horse behavior, who am I, now in my sixties, to condemn that high-flying wild child?

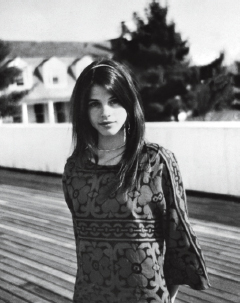

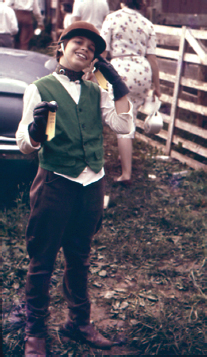

Not so easily forgiven is the girl who dismounted for the last time from her exhausted horse and, learner’s permit in pocket, peeled out of the driveway, double clutching and burning rubber. This is a chapter we’ll cut short: the bleached hair and blue eye shadow, tight pants with what little tatas I had pushing up out of my tank top above them, the many boyfriends, the precocious sexual behavior, the high school intrigues, the vulgar, sassy mouth, the very deliberate anti-intellectualism and provocation.

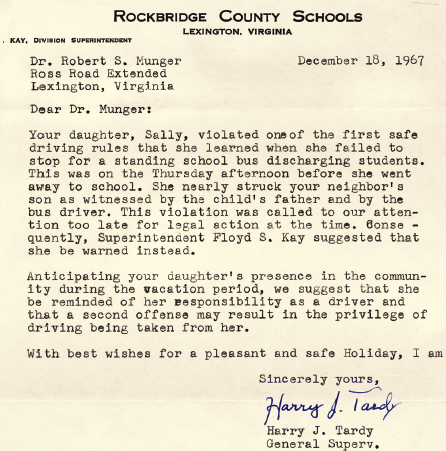

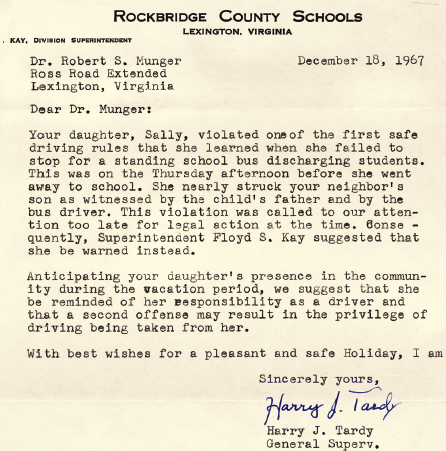

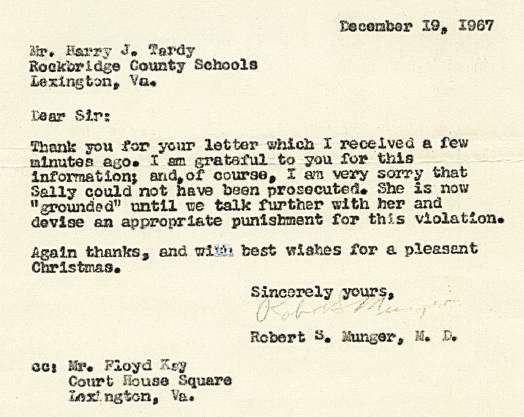

My poor parents. What else could they do but adopt the posture of benign obliviousness that had served them so well in the past? They gave me rules, of course, but at every turn they must have despaired of ever enforcing them. The law, or at least the superintendent of schools, Mr. Tardy, stepped in at one point to whack me for my irresponsible driving, and my father embraced his efforts with what I thought of at the time as unseemly prosecutorial zeal.

I remember this event as if it were yesterday — hell, better than I remember yesterday. We lived at the top of a big hill on Ross Road, and I had been allowed the car to run afternoon errands (who knows what trouble I was really getting into). On the way home, when I got to the hill, I found myself lugging along behind the exhaust-spewing school bus. I knew that bus well, Rockbridge County #54, and knew it was mostly filled with country children often smelling of urine, their teeth rotten, one of them subject to epileptic fits in the aisle of the bus, painfully arcing and frothing until she subsided into a pool of pee, while the bus driver indifferently flicked his eyes up to the mirror and the rest of us exchanged helpless, anxious glances. I had ridden that bus for years and wanted to send it and its occupants the message that I was on my own now, in my own car. When the hill leveled off and the bus began to brake at our neighbor’s house, I downshifted hard into second gear and gunned the car past the bus, not even glancing to see if the folding doors on the far side had been opened to let the three Feddeman children out.

Turns your blood to ice, doesn’t it? It certainly did my father’s, who wrote back to Mr. Tardy, as he says, within minutes. And that was a Tuesday, a full office day with a waiting room overflowing with patients; he was plenty pissed. I’m sure he punished the hell out of me, but I don’t remember it in the way I remember being the asshole who pushed that accelerator.

On the weekends I would head off with my date in his Chevelle or El Camino, my hair rat’s-nested and lacquered into ringlets atop my heavily made-up face, eyelashes curled and matted with mascara, heavy black lines drawn across and well past my eyelid in a Cher-like Cleopatra imitation, lips shiny with cheap lipstick, Jungle Gardenia flowering at my throat, on my wrists, and between my A-cup breasts, which did their best to swell out of a padded bra.

I would generally heave in pretty close to my absolute curfew so as not to enrage my punctilious father unduly and find my parents serenely sitting on the couch in the living room. My mother, with her stockinged legs tucked beneath her, would be wreathed in blue cigarette smoke, deep in the New York Times or Harper’s. My father, a well-sharpened yellow pencil in hand, would be reading with pointy intensity some scholarly paper or plant catalog from the Far East and wouldn’t deign to raise his eyes. Stripping off her reading glasses, my mother would squint through the smoke at me with vague confusion, as though an unexpected stranger had just appeared.

Weaving slightly, I would stand not in front of them but off to the side, as if eager to head down the hall to my bedroom to get some last-minute studying done. My hair, trailing bobby pins, would be matted and tendriled against my hickey-spotted neck, and the skirt of my dress would be wrinkled, the taupe toes of pantyhose peeking out from my purse. My swollen lips were now a natural, chapped red, and my cheeks blushed with beard burn. Peering over the angry marks on either side of her nose left by her glasses, my mother, studying the stone fireplace four feet behind me, would ask casually: “Oh, did you have a nice time, dear?”

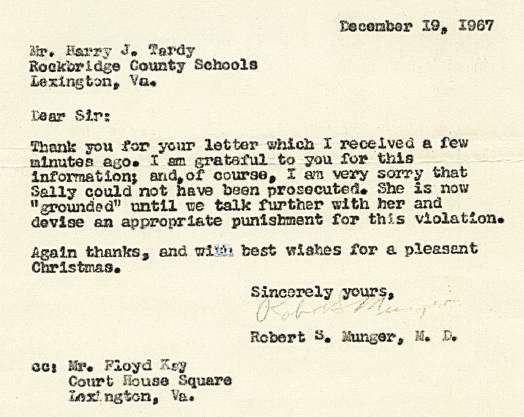

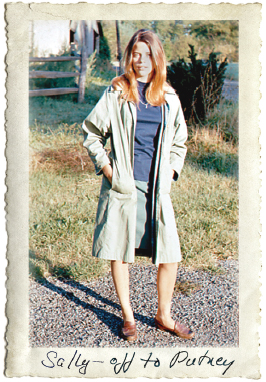

Really, what choice did they have but to send me away to school? My brothers, nine and seven years older than me, were hectoring them to send me to Putney, which they’d both attended and loved. Even I knew, on some level, that I needed to get out of the high school world whose horizon stopped at cheerleader tryouts and drag races on the bypass.

Ray Goodlatte, the admissions director at Putney, must have waived a few of their policies to get me in. In a pattern that has remained constant all my life, my verbal scores were in the ninety-ninth percentile but, oh god, were my math scores abysmal; and my high school grades were only so-so, not always on the honor roll anymore. Most of the kids at Putney were sophisticated children of urban intellectuals with good scores and good grades, fewer than 20 percent from below the Mason-Dixon Line.

Not one would have known, as I did, what a whomping a four-on-the-floor GTO could give a Barracuda in the quarter-mile on the bypass.

So in September of 1967 my mother packed me and my brass-cornered trunk, the same one that my brother Bob had lugged from station to station in New York, into her powder-blue Rambler station wagon and we set off for Vermont.

Halfway there, the car blew a head gasket and died, so we rented a much newer car. In it, as we pulled up to White Cottage, my new dorm, I unknowingly enjoyed the last moment of personal confidence that I was to feel for a long time.

The first week, I raised my hand in Hepper Caldwell’s history class and asked what a Jew was. Hepper (we were allowed to call our teachers by their first names), though startled, refrained from making fun of me, but no such luck from the rest of the class, many of whom were Jews. I was the most ridiculed minority of all: a dumb cracker, with a trunk full of very uncool reversible wrap-around skirts my mother had sewn herself, Clarks desert boots with crepe soles from Talbots, and variably sized pink foam hair rollers. Nobody at Putney had hydrogen peroxide blond hair teased into a beehive, nobody at Putney wore makeup, and nobody at Putney listened to the Righteous Brothers or wore her boyfriend’s letter sweater and heavy class ring, its band wrapped with dirty adhesive tape.

In fact, hardly anybody at Putney even had boyfriends and girlfriends. I was suddenly living in another country where my currency was worthless, where all my hard-earned stock was downgraded. I tried to interest a few of the more likely boyfriend prospects in my wheelbarrow loads of devalued charm and sexual allure, but was met with perplexity and occasionally humiliating disdain.

Confused, but not defeated, I began to mint a new currency based on qualities valued at Putney: creativity, intellect, artistic ability, scholarship, political awareness, and, most important, cool emotional reserve.

Through it all, trying to sort out a whole new life, I ached for home. I missed the embrace of the gentle, ancient Blue Ridge and the easy sufferance of the gracious Shenandoah Valley. I missed Virginia, where sentimentality was not a character flaw, where the elegiac, mournful mood of the magnolia twilight quickened my poetry with a passion that, even read in the hot light of the next day, was forgiven, where the kindness of strangers was expected and not just a literary trope, where memory and romance were the coin of the realm. There I was, desolate with longing, in rawboned, doubt-inducing, unpoetic, chapped-cheeked, passionless Vermont.

The letters I wrote to my parents from that time, cringe-inducing and excruciating to reread, show a clear progression. First come uncertainty and loneliness, but in bouncy teenybopper talk, punctuated with what we now call emoticons, hearts and flowers drawn in the margins. But as months go by, the tenor of those letters changes, and they begin to explore existential questions about the nature of man, the nature of revolution, much discussed at Putney, and the “Negro problem,” as the white problem was termed at the time.

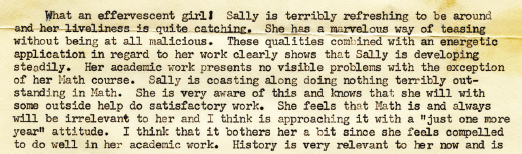

By the time I went home for Christmas break, I had largely sorted myself out. The official reports from my teachers and counselors were all good…

and my brothers and parents were relieved.

I had set the course for what proved to be the rest of my life.

Writing came first. I was frequently the poet on duty when the Muse of Verse, likely distracted by other errands, released some of her weaker lines, but that didn’t stop my passion for it. Beginning in that first year at Putney, I could be found, way after lights-out, crouched in the closet earnestly composing long, verbally dense poetic meditations, almost always in some way relating to the South.

These are the last lands: My blood and heritage.

The seasons, the sky and the soil are within me…

I have asked of the sky

And it gives me the reply of the cyclic ages —

Blistering sun and the cool blink of nightfall…

It offers its knowledge on the flat palm of morning,

For what has not been drawn into its black fist at nighttime?

I return to these lands for the last time.

Languid days of mottled light and sycamore

and nights of thick, sweet violet.

With this sky, this soil, these seasons,

with the Southlands I was born

and with them I grew, and now

I return to them

and to the past which composes them.

I am called by the frail and intangible thread of…

… and so on. You get the drift.

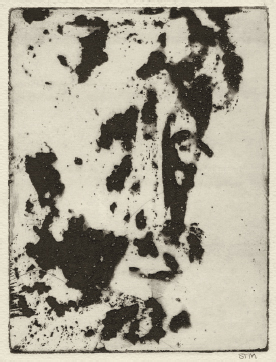

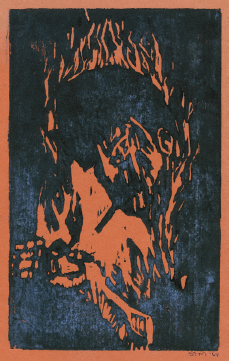

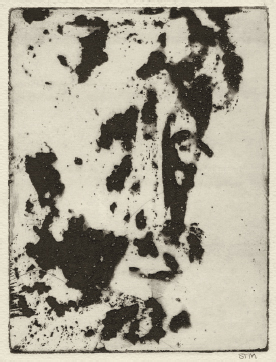

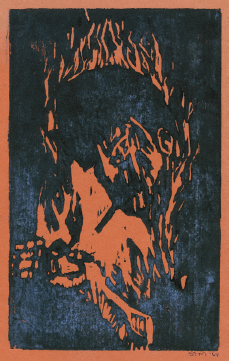

Early on I tried my hand at the traditional arts — painting, woodcuts, pottery, and etchings.

But in none of them was there a glimmer of talent.

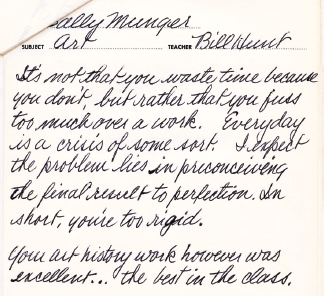

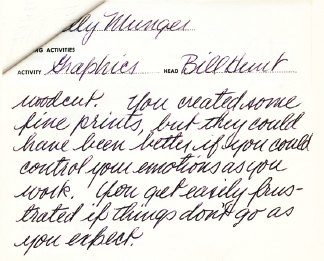

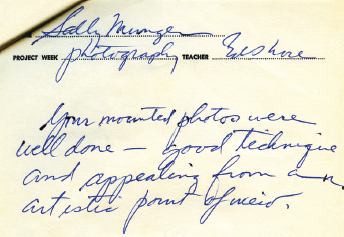

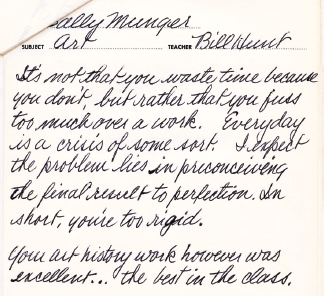

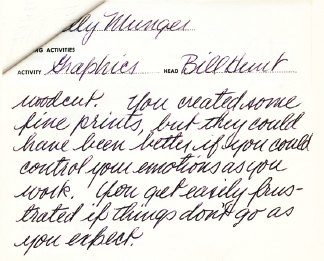

Bill Hunt, my Putney art teacher, had this to say about my artistic practices:

So, so true, Bill.

And then came photography.

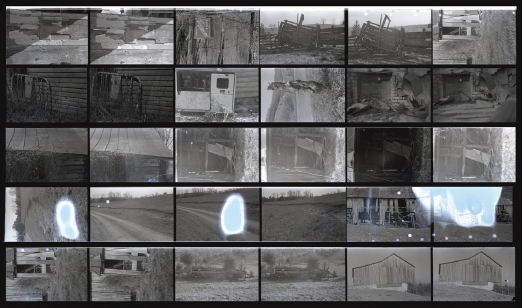

Here is a paragraph from the sprawling, excited letter I wrote to my parents from Putney in April 1969 after I developed my first roll of film, which had been shot on spring break in Rockbridge County with an old Leica III my father had given me.

«I have just returned triumphant from the darkroom. The best photographer in the school helped me develop my film and both he and I were absolutely ecstatic with the results. A lot of the pictures were of patterns of boards, textures of peeling paint on walls and some vines and old farm machinery. But their composition and depth and focus were all really good. I am absolutely frantic with… happiness and pride.… It’s all rather unbelievable and perhaps a total fluke, but really very exciting anyway. God!!»

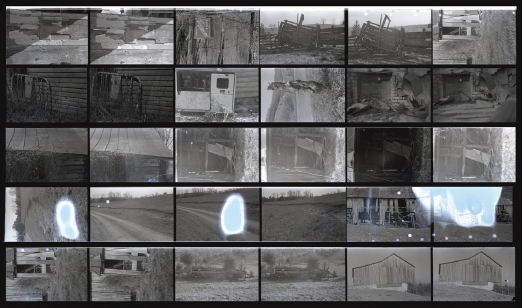

This is the contact sheet of the exposures that survived from that first roll.

Maybe I was high that night, or maybe my expectations were low, but either way, from this vantage point, it’s hard to see what all the commotion was about. All the same, I shouldn’t make fun here of the loopily excited girl who wrote that letter after developing her first roll of film.

Because I am still that girl when it comes to developing film. There is nothing better than the thrill of holding a great negative, wet with fixer, up to the light. And, here’s the important thing: it doesn’t even have to be a great negative. You get the same thrill with any negative; with art, as someone once said, most of what you have to do is show up. The hardest part is setting the camera on the tripod, or making the decision to bring the camera out of the car, or just raising the camera to your face, believing, by those actions, that whatever you find before you, whatever you find there, is going to be good.

And, when you get whatever you get, even if it’s a fluky product of that slipping-glimpser vision that de Kooning celebrated, you have made something. Maybe you’ve made something mediocre — there’s plenty of that in any artist’s cabinets — but something mediocre is better than nothing, and often the near-misses, as I call them, are the beckoning hands that bring you to perfection just around the blind corner.

So, there I was, age seventeen, holding my dripping negatives to the lightbulb, and voicing to my parents in exuberant prose my roiled-up feelings. Maybe I didn’t know it at the time, but I had found the twin artistic passions that were to consume my life. And, in characteristic fashion, I threw myself into them with a fervor that, from this remove, seems almost comical. I existed in a welter of creativity — sleepless, anxious, self-doubting, pressing for both perfection and impiety, like some ungodly cross between a hummingbird and a bulldozer.

Not so different, really, from the way I am now.

My writing instructor, Ray Goodlatte (the same admissions officer who allowed me to squeak into Putney in the first place), prophesied greatness for me in a nearly illegible Putney report:

«You are launched on a lifetime writer’s project. I feel privileged to have seen your work in progress. Your splendid critical intelligence qualifies you, as maker, to receive a high order of gift.… You are a person by whom language will live. I shall look forward to reading you.»

It would seem that having discovered my True Calling(s), writing and photography, and enjoying some academic success, I might tone down the cussedness and rebellious behavior that had defined my life thus far.

But no, not really.

I smoked, I drank, I skipped classes, I snuck out, I took drugs, I stole quarts of ice cream for my dorm by breaking into the kitchen storerooms, I made out with my boyfriends in the library basement, I hitchhiked into town and down I-91, and when caught, I weaseled out of all of it.

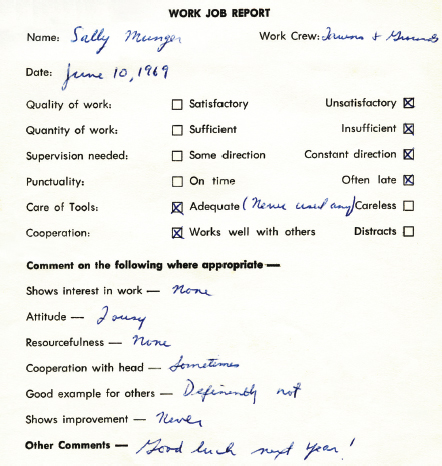

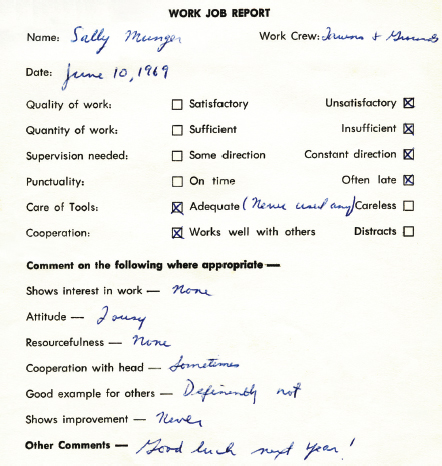

My attitude sucked about the farmwork required at the school.

There is no need to switch on the fog machine of ambiguity around these facts: I was still a problem child.

I got in big, real-world trouble a few times, the kind of trouble that I was barely able to flirt my way out of. Once, while visiting my boyfriend at Columbia, I shoplifted a blouse in Macy’s. I did it in the crudest kind of way, just as I had tucked those quarts of ice cream under my winter cape. Of course, I was immediately apprehended and taken down to the basement, where my dramatic memory has me passing a series of Hollywood-worthy interrogation rooms, painted a celadon color just a bit too far on the olive side, whose lone wooden tables were illuminated by a single bulb dangling from the ceiling. Past those I was apparently led, trembling, to a small, cluttered office. The head of security, an ex–New York cop, stared at me with lowered lids, a cigarette burning in the ashtray.

He’d clearly seen my type before and he let me know, with a snort of derision, what he thought of us. Eyes averted, in a soft southern voice with a goodly amount of throb in it, I tried the “But I’m just a poor Appalachian girl…” routine and he interrupted me by finishing my sentence: “… who just happens to go to one of the most expensive private boarding schools on the East Coast.” I fell to pieces like a dollar watch; I was fucked. I wasn’t scared in the least of this ex-cop, or of the New York legal system. No, I was terrified that this talking piece of dry ice was going to pick up the phone and call my no-gray-ever, all black or white, absolutely moral, never-an-inch-of-wiggle-room-for-equivocations-or-excuses, King of Perfect Rectitude and Repercussions, father.

The ex-cop knew that, of course, and played with me for a while, a well-fed and uninterested cat with a mouse. Then, with a surprisingly avuncular, weary little smile, he stood up, stubbed out his cigarette, and walked me back to the main entrance, keeping his eye on me as I went through the revolving door and out onto the street.

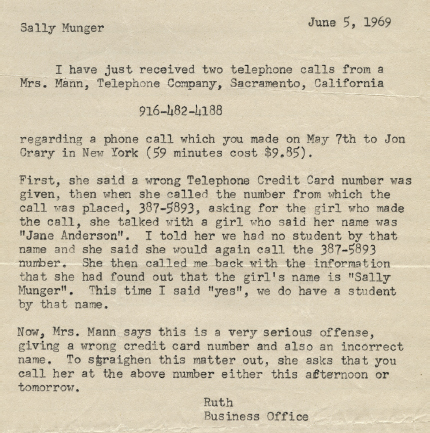

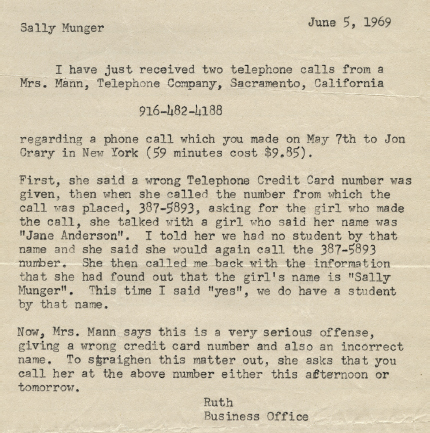

The next time I got into bad trouble, of the full-tilt terror with teeth variety, was when I was given a credit card number said to be that of Dow Chemical, on which to charge my long-distance phone calls to my boyfriend in New York. Of course all of us antiwar radicals hated Dow, so, the way I saw it, it was fine to be charging my calls to their number. After all, Dow Chemical was burning babies alive with flaming jelly. How bad were a few little phone calls within the scope of that evil?

And besides, they were never going to catch me.

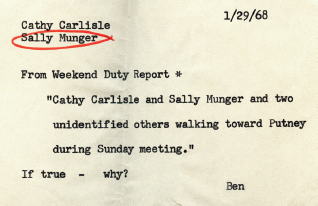

Of course, it’s only now, finding this letter stuffed into the pages of my journal, that I note the irony in the name of the telephone operator.

So, my parents, with ostentatious righteousness, paid up and punished the snot out of me, again. For two weeks when I got home after graduation they worked me like a rented mule, making me haul thorny brush and all uphill, too.

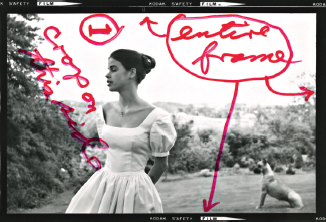

I even got in trouble at Putney with photography, and right about the same time as that phone call, a week or so before graduation. Having loaded my second-ever roll of film into the Leica on a beautiful sunny afternoon, I headed off with my friends, my roommate Kit and her boyfriend (let’s call him) Calvin to a stand of pines adjoining the school. There they stripped down and let me photograph them in a series of completely harmless nude poses.

I shot only twenty-four images, eight of which were of Kit lying alone in the grove, my attempt to imitate one of my favorite images, that of an incandescent bare-naked child in a forest clearing by Wynn Bullock in The Family of Man. Afterward they dressed and we settled down to the real business of rolling cigarettes and drinking gaggingly sweet sherry out of a clay jar I had made in pottery class.

With the same dumb naïveté to which I am unfortunately still susceptible, I never considered the images anything other than a sweet meditation on the figure. And, indeed, that is all they were. Both Kit and Calvin were strikingly beautiful; sunlight dappled the pine-needled forest floor, and I was keen to expand upon the successes of my first roll of film. Nothing in the pictures suggests that anything of a sexual nature had taken place.

So, you might wonder why I’m not showing you the contact sheet of this photo shoot, as I had originally intended. That’s an interesting question.

And the answer, as ever, hinges on the power, interpretative lability, and multifarious hazards of photography itself. In preparing this book for publication, I contacted Kit and Calvin about using the pictures. Kit, now a semiretired medical doctor, responded with alacrity, saying she was honored. Not so easy with Calvin, who was at first delighted to hear from an old school chum but then had second thoughts. He wrote that he was no longer a happy-go-lucky youth, and that he was now working “in a corporation with political colleagues,” and that “the photos could suggest that teenaged sex has or is about to take place.”

So, respecting Calvin’s fear of being mistaken for someone who might have had teenaged sex forty-five years ago, I won’t show you the tender and unambiguously nonsexual pictures I decided to print up that spring at Putney. Images can have consequences.

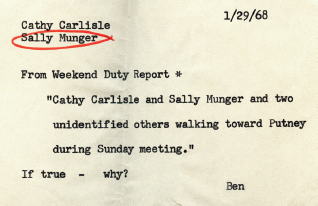

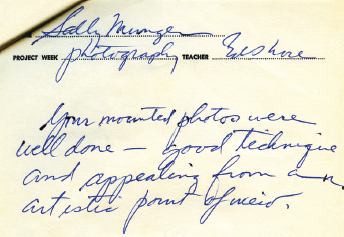

They had consequences then: within thirty-six hours there I was sitting, not for the first time, before furrow-browed Ben Rockwell, the headmaster. I wasn’t surprised to discover that it had been the photography teacher, Ed Shore, who had turned me in. My photography teacher took pictures to the headmaster and said, I think this girl is violated the honor code not to be kicked out. He had submitted this report on my work a few weeks before:

Oversensitive and insecure, I felt it to be lackluster and somehow read “appealing from an artistic point of view” as a pejorative.

Shore turned me in for inappropriate subject matter but also probably for sexual misconduct, of which I was guilty in a general sense, but it was a charge I resisted vehemently in the case of this perfectly innocent afternoon. That actually did kind of shake me up because I didn't want to get kicked out of school.

I showed absolutely no talent whatsoever. If I was one thing, I was incompetent, I just could never quite master the technique but I thought I wanted to be a writer and probably a poet and the photography was just something that I did as a pastime. It was easy compared to the poetry, that's for darn sure.

With the force of that conviction I oiled with charm and denials the choppy administrative waters and despite the now-familiar threat of expulsion ultimately took my seat, to the strains of Bach’s Magnificat, in the graduation procession.

Many times on my account that bending arc of the moral universe has allowed me a bypass in its route toward justice, maybe because I was flat lucky or maybe because, if you want to think cosmically, some redeeming attributes justified the detour. Difficult I was, conniving I was, without a doubt rebellious I was, but six months after squeaking out of Putney the universe gave me a pass on all of those things, bringing me face-to-face with Larry Mann.

Those who say I am lucky to have found him are right.

The Family of Mann

After Putney and a wayward summer writing poetry and taking pictures in Mexico, I enrolled at Bennington College, figuring it would be pretty much the same as Putney, forty-eight miles away. I wasn’t any fonder of being way up north, but it was a known quantity, as opposed to Sarah Lawrence or Barnard, schools that I decided were too urban for me.

Flying the familiar route on Piedmont Airlines to tiny Weyers Cave airport, I arrived home for Christmas in 1969 and finally met Larry, three months after our destiny, unbeknownst to us, had been sealed on the afternoon he moved the epic stone. The farmhouse where my Lexington boyfriend lived had an odd layout, and one night as I slouched in a satanically bad mood on the edge of his bed, Larry walked through the room to the shared bathroom. I had no idea who he was, he did not so much as glance in my direction, but my eyes followed him with a warm, glittering interest. We were married six months later.

~

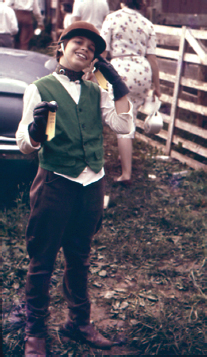

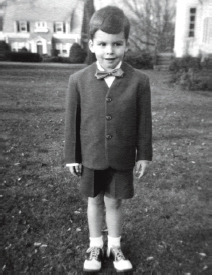

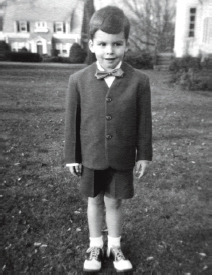

Everything about Larry’s past, not just his horse history, was the opposite of mine. Where I had that laissez-faire, semi-neglected, rural upbringing, he had a suburban New Canaan, Connecticut, childhood of parental pressure, social climbing, and embarrassing excess. As a toddler he was dressed in starched sailor suits, brass-buttoned, double-breasted jackets, and bow ties.

Just by way of comparison, at roughly the same time, this is what I was doing.

By the time I met him at twenty-one, he owned five custom tuxedos: white ones, everyday ones (apparently there is such a thing as an everyday tuxedo), and a black one with tails. His starchy tuxedo shirts hung in his closet like expectant armor, and blue boxes with engraved cuff links shared his dresser drawers with freakishly uncool madras cummerbunds.

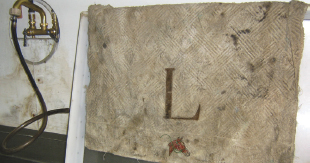

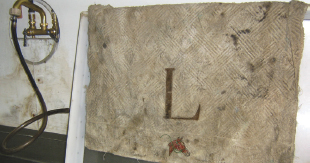

Since the age of fourteen he had been instructed to hand out embossed Tiffany calling cards. His sterling silver hairbrushes were monogrammed, and it wasn’t just them. Everything was monogrammed: the Brooks Brothers shirts, his sheets, towels, even the most diminutive washcloths. And of high quality, too. This one is still serving me as a darkroom towel some fifty years later.

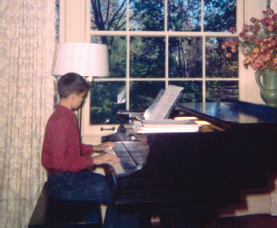

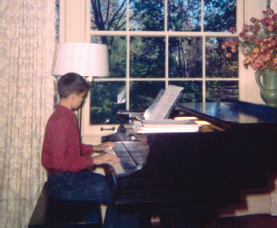

Since the time he could stand up to pee, he had been given dance and etiquette instruction, and then came private piano, tennis, swimming, skiing, and art lessons. To appear to have been born into the upper classes, Larry had to memorize Emily Post right down to the footnotes. He knew how much to tip the washroom attendant at the opera, when to pick up the fish fork, how to cut in on the dance floor. His diction was perfect.

The rules were smacked into him by his mother, Rose Marie. She was a commanding woman, tall enough to hold her own against Larry’s six-foot-five father, and she had glossy black hair that in middle age sprouted a striking white forelock.

Formidable enough right there, but by the time she was getting down to the serious work of beating on Larry she was quite hefty. She hadn’t started out that way; in fact most of the pictures we have of her in her youth show a beautiful and slender young woman. But she bore a torment within her. She had been born in 1925 to a young, unmarried Little Rock woman and put up for adoption at birth. That in itself should not be a problem, but for some reason her adoptive mother passed her on a few years later, like a hand-me-down dress, to her younger sister.

Just guessing, but I’d say that might make her want to light into someone with an oversized wooden spoon, as she did with Larry. And maybe the fact that after she moved to Chicago and fell in love with the jazz that she heard there, her priggish young medical student boyfriend, Warren Mann, insisted that she throw away all her 78 rpm jazz records, reminders of those good times, and attend to the business of being a doctor’s wife — that also might make one want to bring out the spoon.

But which of the two newlyweds was more dedicated to improving their social status is hard to say. They both appeared to be scrambling up the ladder in tandem and with a similar and relentless desire for a higher rung. Warren was a young shrink on the rise, and during the years when Larry was still small enough to be smacked around, Dr. Mann was enjoying a stimulating and prosperous practice with some highly placed Greenwich and New Canaan socialites under his care. Rose Marie was, even for a socially conscious town like New Canaan, stunningly class-conscious and all too aware of her humble and murky origins.

Whatever the reason for her fury, she vented it so often upon Larry that when I first met him he would still flinch at a sudden movement of my hand toward his face. If he inadvertently allowed his forearm to stray from its proper position at the family dinner table, his mother would stab it with her fork. To this day, there are tine marks in that cherry-veneer dining table testifying to the quickness of Larry’s reflexes.

Gangly, solitary, over-mannered, mistreated at home, Larry was painfully aware of what his parents were doing, their obvious ambitions for him, their manipulations and control. He describes himself during this time of his life as a prisoner, and like all prisoners, he contrived subtle ways to preserve some independence. For a time he was allowed to go to school and return on his own, but his mother insisted on dressing him in Lord Fauntleroy–like outfits. Trying to fit in at school, he would switch them out at the end of the driveway for cooler clothes he kept stowed in a bag under a bush, reversing the process at the end of the day.

In general, when he was not in school or at after-school lessons, he was confined to the home, where he could be protected from the influences of the common world. But the fatal mistake in that strategy was that, alone in his room, he found the prisoner’s treasured sliver of daylight, the soft tapping at the walls, the hidden hacksaw: he found books.

Along with a purchase of the Encyclopedia Britannica his parents had also bought, as library ornaments, the fifty-four Great Books of the Western World. They never suspected the subversive potential behind all that gleaming leather and gold. Larry read damn near every one of them, methodically moving along the shelf: Homer, Sophocles, Plato, Aristotle, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, Locke, Hegel, Melville, Tolstoy, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Dickens, Twain, and Heidegger. These great minds cracked open the door and gave him a peek at his legal future, although at the time, of course, he didn’t recognize it as such. He became a philosophy major in college and eventually, through a program started by Thomas Jefferson encouraging self-disciplined but impoverished Virginians to become lawyers in that state, he “read the law” for three years to become an attorney.

As though he were practicing for the long hours in his future with dense law books, Larry would read alone as the afternoon sun leveled its rays through the gap in his curtains and the sounds of the children playing outside diminished. He would be so lost in reading that he would miss the call from his mother to change to the more formal dinner clothes that were expected at every evening meal. In the exhilarating world of ideas, he found himself free for the first time in his life, teaching himself in the process to be content alone, to read carefully and to reason, and most of all, to watch and listen.

~

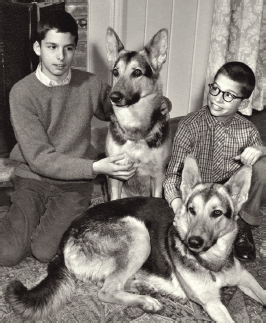

You’d never know it by looking at the parents’ allocation of resources and time, but there were two sons in the Mann family, Larry and Chad, two years younger.

The Manns had chosen to concentrate their efforts on Larry, probably because of his exceptional good looks, tractability, and general social ease. Directly inside the front door of their home was a large, gilt-framed painting of Larry the equestrian executed in the fawning style of an ancien régime court artist. Nowhere in the house was there any sign that there was another child in the family, no pictures or trophies or framed diplomas. Chad also came in for physical abuse by his mother, but he surmises that because he wore glasses he didn’t get the hard facial slaps that sent Larry to school with his ears ringing and reddened, and instead got just the spoon and the brush. Except for the beatings, Chad was basically ignored, which in a way was a blessing.

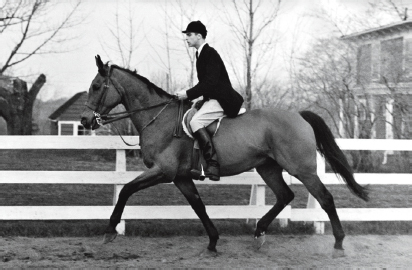

The Manns zeroed in on the horse world as the best place to show off their handsome son and to make contacts with the right kind of people. Every afternoon after school, Larry was picked up by his mother in a Mustang convertible, her bouffant covered by an Hermès scarf, and driven to Ox Ridge Hunt Club for intensive lessons in dressage and jumping by their top instructors. In fact, he loved horses and riding, even ring work and the fancy horse shows. Like me, he found time on a horse transcendent and healing in some way, but especially in the less structured disciplines, playing polo, fox hunting, or occasionally just galloping on the cinder paths that lined the fields.

While his mother drank martinis at the club bar, Larry hung out with the forbidden groom underclass and realized, all the more clearly, the trap into which he had been born. But even into his late teens he remained pliant, escorting the daughters of the rich to balls at the Ritz while, with the avidity of a Spanish conqueror seeking Inca gold, his mother scoured the hunt clubs and society pages for just the right wealthy daughter-in-law.

The girl Larry brought home in spring 1970 was far from meeting any of their criteria.

“She goes to Bennington??” they had asked incredulously, responding to the news of our romance as if he had found me in a leper colony outside Baton Rouge. Implacably, Larry said yes. Bending to his unexpected defiance, they offered a grudging invitation for me to visit. When Larry and I arrived over Easter, his mother placed a Lilly Pulitzer outfit on the bed in my room as an alternative to my 501s and Frye boots. I decided right there that she was a ring-tailed yard bitch. The feeling was clearly mutual.

At the midday Easter dinner, when we announced we were going to get married in six weeks, his parents and grandparents burst into tears and left the table. We looked over at Chad, who raised an eyebrow and smiled, then, spooning mint jelly onto his plate, continued eating. We did the same and, that night, Larry crossed from his bedroom to mine and we made noisy love before leaving at dawn. We found out later that after that week his parents made an appointment with their lawyer to cut Larry out of their will.

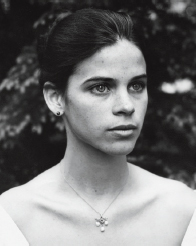

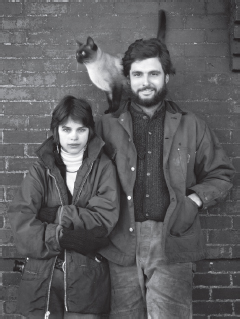

Their disapproval only increased our determination and the perverse pleasure we took in our unacceptable love. The preparations for the wedding were easy: we bought two simple gold rings at Ed Levin’s shop in Bennington and I designed a demure cotton dress that I had a local seamstress stitch up. My father dusted off his Linhof and shot a few pictures, one of which Larry’s parents grudgingly put in the New Canaan newspaper.

The one that didn’t make it into the paper is the real portrait, capturing the fey, Golightly feeling of the weeks before the wedding and, not incidentally, the Great Dane Tara in the background, the dog that had run my mother out of her marriage bed. My mother salved her injured feelings by purchasing the biggest Zenith that Mr. Schewel had in his showroom and moving it into my old bedroom, in defiance of my father’s rip-snorting disdain for and prohibition of television in our home. My brother Chris and I date the moment when a TV was allowed in the house as the end to the family dynamic as we knew it, and the beginning of a corresponding decline in our mother’s intellectual acuity.

Meanwhile, Larry’s parents ostentatiously refused to come to the wedding, making a point of starting every phone conversation with, “Don’t think for a minute that we’re coming for your wedding.” Certainly they sensed our see-if-we-care shrugged shoulders as we replied, “It’s okay, don’t.”

So they did. Two days before the June twentieth wedding they announced they’d come but only, in their exact words, “tanked up on Miltown.” I dreaded to see the bagful of spiders they would surely pull over our heads but, sedated, they were the picture of probity and forced good cheer. At dinner the night before the wedding, they made a show of announcing that they were giving us a car as a wedding present, and around the table was rejoicing — and relief. It seemed that they had made peace with the marriage and would finally embrace our union, as disappointing as it was to them.

The wedding was held a little after dawn in my parents’ garden. It was modest; only our two families and a few friends attended — there couldn’t have been more than two dozen people, tops. We had some difficulty finding someone to marry us because there was no mention of “God the Father” or “the Holy Spirit” in our handwritten vows. We solved it by reading aloud the E. E. Cummings poem “i thank You God for most this amazing day,” that first line satisfying the God requirement, and, as for the Holy Spirit, we figured Cummings had it covered in “the leaping greenly spirits of trees.” The almost childlike lack of punctuation and capitalization that characterizes Cummings’s poetry and his affirmation of the natural “which is infinite which is yes” somehow caught the innocent spirit of those barefoot nuptials, our green optimism, and the wingding gaiety of the day.

Another sure proof of the divine presence was that the man who married us, David Sprunt, looked like the brilliant offspring of a coupling among God himself, Judge Parker from the funny papers, and Atticus Finch.

A small reception followed and, for a moment at least, Larry’s parents, there on the left with Chad, deigned to step into the picture with their new in-laws, whose heedlessness of status, unconventional tastes, and political liberalism they despised.

It was a near-perfect day from our point of view: low-key, modest, and relaxed. And cheap, as my delighted mother would report afterward: the most expensive part of the whole thing was the wheel of Brie.

We honeymooned at the cabin on the Maury, of course.

The wedding may have been cheap, but my parents were generous with their gift to us, a check for $1,000. Right away, we deposited it in our newly opened joint account, and it comprised every cent we had. We were nineteen and twenty-two, and for us this was a fortune. Now I look back at that endearingly optimistic, cash-flush young couple with the rueful headshake of an old marital veteran, many cash-flow wars behind her.

We still needed the promised car and a few months after the wedding found one that would suit our needs: a used front-wheel-drive Saab station wagon. With the taxes, it topped out at $990. Perfect! We called Larry’s parents, told them about our choice, and they said airily, “Just go ahead and pay for it and we’ll pay you back.”

Of course we should have known what was going to happen next, so eager still were his parents to sabotage the marriage, but when it did, we were knocked flat with the disaster it meant to our young lives together. I have not forgotten the cruelty in his mother’s voice when we called to see when they could repay us. Mockingly, she began the predictable sentence with something like, “Oh, please, did you really expect we’d…”

Despite this treachery and its damning financial consequences for the start of our marriage — a ten-dollar bank balance being all that remained from our wedding present — we toughed it out. Larry’s parents continued to do everything they could to undermine our relationship, such as giving us expensive carving sets for Falstaffian cuts of meat that we could not afford, knowing full well we were eating out of a twenty-five-pound bag of soybeans that also served as a beanbag chair in our basement apartment.

Through those rough years we clung to each other tenaciously: I sure wasn’t going to give them the satisfaction of seeing us come apart. We were flat broke, always, and my parents, for reasons I have never quite figured out, did not offer to help, paying only my tuition and a small food and housing allowance. But now, in retrospect, I believe that made us stronger. Not that any of it was fun. Not at all.

After we had been married seven years, late on the night of July 21, 1977, Larry’s mother rose from bed and stepped over her underwear lying on the floor, its crusty yellow crotch facing upwards. She walked to the closet across the room and pulled out a Stevens single-barrel 410 shotgun and a box of shells. Returning to her side of the bed, she sat next to her husband, who was covered up to his chin with a light summer blanket, sleeping on his back, his left foot casually crossed over his right. Breaking open the gun, she loaded one shell and clicked shut the breech. Then she pressed the muzzle tight against the back of his head between the ear and the midline and blew his brains out the other side.

We’ve wondered whether he registered the lock of the breech or if his eyes foggily flicked open at the cold touch of the barrel against his head. And we’ve speculated on how long she sat there afterwards, ears ringing with the blast, the air pinkly misted with blood. The pillow and sheets were a ruin of tissue and bone, and a dark stream was running from her husband’s right nostril. Except for the slightly elevated left eyelid revealing a sliver of dull eye, the crime-scene photos show that his face was intact and looked to be that of a handsome deep sleeper, an incongruously debonair Superman curl of black hair drifting across his forehead.

Here’s the thing, buried in the police report, that I thought strange: after she fired the gun, Larry’s mother picked up the ejected shell casing and carried it, still warm, across the room to the trash can. As if, in that scene of murderous disorder, one spent shell casing was just too much mess.

Who knows how long it took her to reload the gun with the second shell, and adjust the two pillows behind her head so her upper torso was slightly elevated. Placing the stock between her legs, she fed the gun barrel up into her mouth. When she pulled the trigger with her left forefinger, the wad of the shell exited ferociously from her forehead.

The air conditioner continued to run for three days until a friend who had come to the unlocked front door heard the barking of the frantic, starving German shepherds who had the run of the downstairs. He called the police, who somehow pushed the dogs into the kitchen and went upstairs to find the bodies.

When we arrived at the house the next day, nothing except the bodies and bedclothes had been moved. On the living room rug were several weeks of unopened mail, each day in its own pile, and dog shit smeared by frantic paws. The curtains were all closed tight, just as they had been for weeks. Upstairs, the underwear, somehow for me the most disquieting thing, was still untouched on the floor. Was it a testament to her suicidal state of mind that she hadn’t reached out with her big toe on the way to the closet to flick them over into the corner? Or was it her final Fuck You to leave them there?

The contents of the bathroom said Fuck You, too, fuck the New Canaan society she so wanted but couldn’t get into, fuck the country club, and fuck her husband’s medical reputation. It was awash with prescription drug bottles, many empty, the mirrored medicine cabinet door hanging ajar. A deep, multishelved bathroom closet and a closet outside in the hall each held a cornucopia of prescription drug bottles, way more than any two people could use in a lifetime.