The Naked Child Growing Up Without Shame

<< Chapter IX >>

Immediate Family

Sally Mann

Our Farm — And the Photographs I Took There

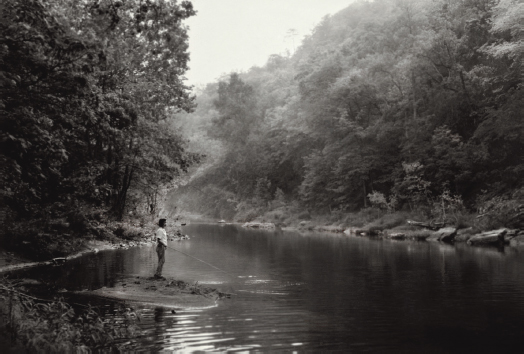

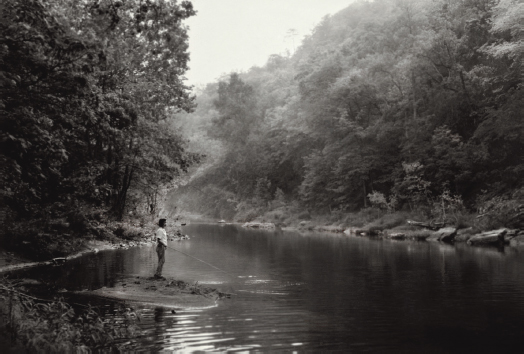

I recently flew down the Shenandoah Valley on my way home from New York. As we began our descent into Roanoke I easily picked out my own sweetly unassertive Maury River, which heads southeast about two-thirds of the way down the valley. For its entire forty-three miles it flows through Rockbridge County, during which it goes fairly efficiently about the riverine business of dumping itself into the mighty James. But about midway through its course, the Maury seems to pursue one extravagantly wasteful detour: the big, languid loop with which it almost encircles our farm.

Even from 15,000 feet this anomaly is easily seen, resembling the shape of a boot, with the hint of an unsubstantial heel at its nether end as the river straightens out again, heading single-mindedly toward the James at Glasgow.

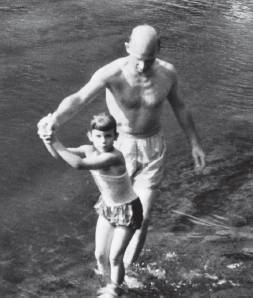

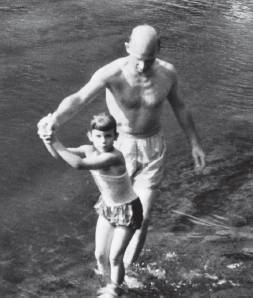

This beautiful river, and the cool of its overhanging sycamores, brought my father to the offices of a local veterinarian one Friday afternoon in 1960. Daddy was looking for a couple of acres on which to build a cabin for a family retreat, and the vet had a farm on the Maury. They had come to an understanding by phone about a stretch of bottomland and agreed to settle the deal after their respective office hours that afternoon.

Later that same evening, as my mother dressed for cocktails, turning in her full skirt before the mirror attached to the back of their bedroom door, Daddy announced that he had just purchased not the expected two acres on the river but three hundred and sixty-five. He spoke nonchalantly as he leaned over to buff his shoes, sitting on the miniature chintz-covered chair reserved for this purpose. In midturn, her skirts hissing to a standstill, my mother froze before the mirror, her startlingly teal-colored eyes staring at the reflection of the man unconcernedly putting the last swipes down on his brown Stride Rites.

I wonder if most marriages of that time, fulcrum-based as they always have been, were as lopsided as this one, or whether my parents’ was so lopsided because of the weight of my father’s personality on the marital seesaw. He certainly didn’t cause the asymmetry by displays of physical strength, anger, or unkindness. To the contrary, he moved quietly, his sinewy physical power concealed by the blocky way he dressed. Maintaining an air of distraction as though in profound thought, he seldom spoke, and, when he did, it was with a mannerly, almost tender gentleness. How is it, then, that we were all so intimidated and awed by him?

My mother, helplessly astride her insubstantial end of the seesaw, lacked the personal confidence and gravitas necessary for spousal balance with such a partner. Announcements to her of unilateral faits accomplis from the weighted side of the board, such as the purchase of the farm, were among the ways that my father further lightened her end, whether he meant to or not. What did he know about taking care of a large property with barns, tenant houses, pastures, forest trails, a rusting sawmill and fencing to maintain — and with what resources? He was, as we say about the novice farmer, all hat and no cattle, all hawk and no spit. But, as so often happened, this whimsical purchase was his decision alone. My father had never laid eyes on the farm he had just bought, writing without hesitation a personal check that Friday afternoon for the $75 an acre that the vet had spontaneously thrown out as a price, saying, “Oh hell, Bob, never mind the two acres. Why don’t you just take the whole thing?”

And so, the next day, Saturday morning, my parents drove out Route 39 to look at their sudden new farm. With trepidation, they turned off the pavement onto dusty Copper Road, at the end of which was a drooping gate. Unlocking it, they passed into land so rich in beauty and perfect in proportion that by the time they unwrapped the wax paper from their sandwiches, sitting opposite the cliffs on the sunny beach where later they built their cabin, they were speechless with relief and happiness.

Stunned as well (it turns out) was the vet’s wife when she found out that her husband, without consultation, had sold the very farm their sons were depending on for their future livelihood. I wonder if that shocking news was delivered to his wife with the same nonchalance that Daddy delivered his, but the vet heeded his wife’s distress and wasted no time in calling my father to back out of the deal.

Having seen what he had purchased, my father was not about to give it back. But, as a way to minimize the farming family’s disruption, he allowed their son to farm it for another forty years. Our family’s contact with the farm was generally limited to holidays, and the memories we made there were correspondingly intense. We cut our Christmas trees from the edges of the forest and spent summer weekends at the cabin, a simple structure my father and brothers began building in 1961.

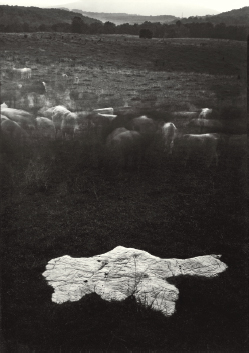

But, without anyone from our family living there, the farm went downhill. The pastures were a tangle of devil’s shoelace and stickweed, with a few gallant saplings trying to make a go of it in the played-out soil. All the barns were rickety, with unpainted and leaky roofs, the tenant houses unlivable, the fences trampled by hungry cattle, and the roads impassable with ruts. In spite of the superficially terrible shape it was in, the land still had what my mother called “good bones” — beautifully undulating pastures, partly the result of our sinkhole-prone karst geology, extensive, cliff-protected river frontage, mountain views, old-growth forests, and a sense of deep privacy and sanctuary. My father deeded the farm to my two brothers and me in the 1980s, but, of the three of us, I was the one with the closest proximity, the greatest ability to maintain it, and arguably the strongest feelings about it.

And boy, were they strong. My feelings were of the most vital, the sine qua non, the fight to the death, the lie down in front of the bulldozers, forgo all food and water, but never, ever lose the farm variety. I had loved that farm since the day we got it. At age twelve I galloped bareback through pastures mined with groundhog holes, swimming Khalifa in the river to escape the flies, and fishing until it was too dark even to see the pale albino carp floating in the shallows.

What momentous family event did we not celebrate on the farm, what birthday, holiday, anniversary? There is no sinkhole into which we have not poked our walking sticks, no time-stretched initials carved in smooth beech bark that we have not traced with our wondering fingers, no deer trails unfollowed, no cliff from which we haven’t dislodged medium-sized stones to make large-sized holes in our waiting canoe below, no deeply romantic swimming holes unsounded. The farm is a constant for all of us, glowing steadily in the unreliable, teasingly labile shadow of memory.

~

After I was sent to boarding school I wrote heartbroken love poems to the farm. Among my first curling, yellowed contact sheets of 35 mm images are dozens of pictures taken there.

When I began photographing with my 5 × 7 inch view camera, of course I hauled it out to the pastures, the woods, and the cabin.

Heartbreakingly, when I went to my storage box to pull the negatives of these images, the emulsion of every one was reticulate with cracks. They had been destroyed by vinegar syndrome, which afflicts certain “safety films” introduced early in the twentieth century to replace flammable nitrate film, the film on which my father made his images. Here’s what they all look like now.

~

My manifest farm passion did not put me in a good bargaining position when I approached my two brothers to buy out their parts of the mutually owned property. They, reasonably enough, thought of it as their patrimony, but a fungible one. It was clearly our only inheritance, as a very modest sum remained in my mother’s account after my father’s death in 1988. The farm was basically all that was left for the three of us.

Of the predictably biblical, epic, and divisive negotiations involved in establishing a value for the farm, the less said the better. Only a gorgeous piece of good land can provoke that kind of piercing despair and dispute. Failed loves, complicated family relationships, broken hearts, errant children, lost lives — nothing so engages a southern heart as a good piece of family land.

But, having agreed on a price many decimals removed from the now mythical, fairy-tale-sounding $75 an acre my father paid, in early 1998 Larry and I walked into the local Farm Credit office and asked to borrow 100 percent of the purchase price for a farm upon which we were immediately going to place a conservation easement, thereby lowering the value by 30 percent.

The loan officer looked skeptical. I explained winningly that we would surely be able to make the mortgage payments with the sales of as-yet-untaken images of the Deep South, a trip on which I would be embarking the afternoon of the closing. Bless his heart, taking a look at my camera, portable darkroom, provisions, and maps in the Suburban parked outside his office, and infected with my confidence, he said okay. We had the loan.

We celebrated that night at the cabin, the repository of so many memories, but before I pulled out the next morning to head south, I made sure the cattle-running tenant was notified to take his stock off the farm and never come back, remembering my two horses, Fleet and Khalifa, he sold to be slaughtered.

~

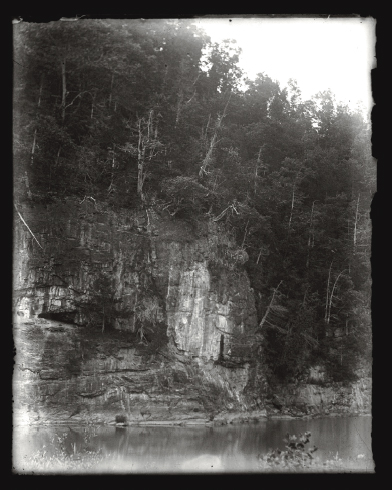

Featured in so many of my photographs, the cabin perches at the very apex of the Maury River’s exceptional oxbow around our farm. Emerging from the woods into the clearing where the cabin sits, the first-time visitor must crank back the noggin as the amazed eyes begin their long climb up the multicolored, New Mexico–looking cliff face towering over the river.

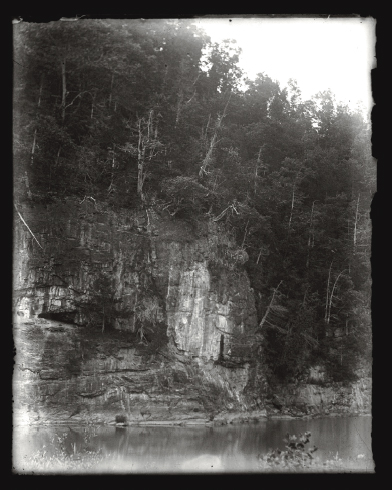

Scraggly arborvitae cling tenuously to it, or hang by their last roots — the same trees, in fact, that appear in a glass negative taken at this site in the 1860s by a returning Civil War veteran, Michael Miley.

Back in my early twenties, I had discovered some 7,500 Miley glass-plate negatives stored in an attic on the Washington and Lee campus. I knew Miley had photographed Robert E. Lee in retirement here, but the negatives I found included none of those relatively famous images. Instead I found pictures of familiar local places, many all but unchanged in the intervening century, among them several of the stretch of river where the cabin is now. This dark pool was a popular swimming hole in the 1800s, and it is easy to imagine that Lee himself swam there or, even more likely, Stonewall Jackson.

As I held those dusty Miley plates to the light, in the same careful way I now hold my own glass negatives, I found myself weirdly shifting between the centuries. In that same time-warpy way, the view we see now from the cabin deck has remained virtually unchanged for 150 years: the arborvitae pictured as a sapling in front of the cave opening in the Miley image almost certainly is the fallen, bleached tree trunk off to the left in this modern photo.

The grandson of a county native recently gave me a written account that describes a camp in the late 1800s where the cabin is now. Its name, the Covenanter Camp, would have pleased Stonewall Jackson, alluding to the religious and military history of the Scotch-Irish Presbyterians who first settled the area. The camp director, indeed, was a grizzled Confederate veteran who ran the place on rigid military lines. Surprisingly, it was coed, with twenty-five girls and seventy boys at the two-week session. A tent city was erected with a central “Main Street” dividing boys from girls, and a large cook tent anchored the operation.

Apparently, scheduled activities were few. Mostly the kids swam and raced and threw horseshoes, and once, for sport, in the absence of a pig, they greased and chased a kid named Tricky Johenning. Until the large beach along the river at the camp was literally sold out from under them to a man in need of sand to make brick mortar, the Covenanter Camp prospered and the kids played tirelessly on the beach and in the river.

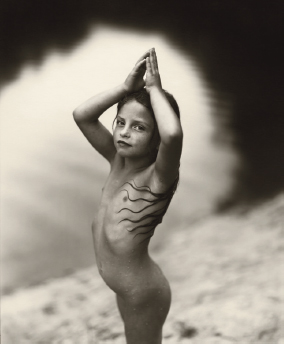

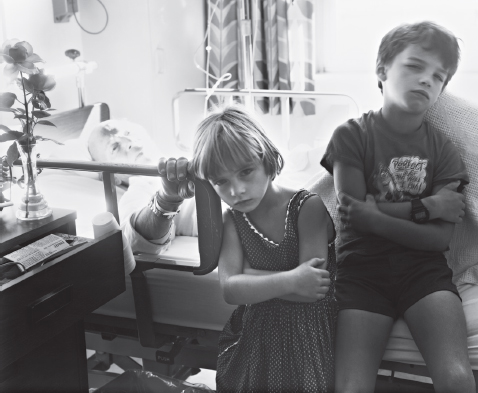

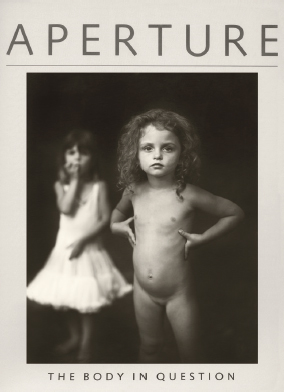

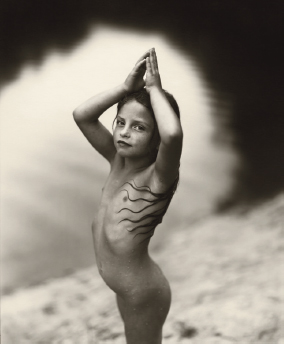

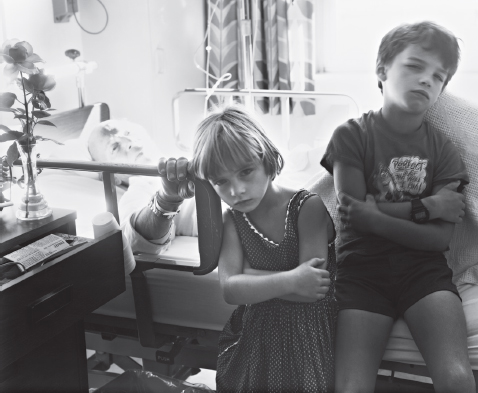

Nearly a century later, so did our three children, Emmett, Jessie, and Virginia, not nearly as well covered up and making do with a smaller beach, but enough of one to serve the purpose for sand burials, castles, and sunbathing. On that beach and by that same river I began taking the family pictures, consisting of at least two hundred final images, some sixty of which were published in 1992 in Immediate Family. These pictures cannot be understood without the context of the farm and the cabin on the river — the intrinsic timelessness of the place and the privacy it afforded us.

I was afraid that being in Lexington where there's no feedback and no stimulus was to make art in a complete vacuum. I was frustrated for four years, gave a lot of thought to moving to New York but ruled it out. This is a very compelling place to live.

Hold Still

The way I approach photography, it's very spontaneous. The children were there, so I took pictures of my children. It's not that I’m interested in children that much, or photographing them, it's just that they were there.

When I had my first child I began working on a project photographing children or what I thought were children, I began photographing 12 year olds. I started by photographing one girl and was struck by how compelling her inner turmoil seemed today, I mean, she just spoke to me and I took her picture and then I afterwards asked her how old she was and she said 12 and, of course, it made perfect sense to me that was the reason that she had this so much emotional power was because she was 12. Twelve being that transitory time between girlhood and womanhood where you're just like a little tiny fledgling bird on a wire where you're just taking flight and I tried to explore all those concepts: the concept of of their independence and the concept of their anxieties and their dependence on their parents and their independence from their parents, and it's a very complex time. And I tried to explore all the ramifications of that particular period in childhood just as I've been trying to explore the implications of being a very young child in this new series of artwork.

I get asked a lot by people whether or not these pictures reflect the children's actual life. And perhaps, maybe it's my past that I'm photographing. It's an intriguing thought, it's doubly intriguing, because I don't remember my past. I have almost no memories of my childhood, so that there's some question even in my mind as to whether or not I might be creating a past for myself in these pictures, a past which I otherwise don't have or wouldn't have. And that's it gets into really uncharted waters and I can't answer.

My feeling about the pictures I make hadn't really changed. There's a lot of emphasis on beauty and the pleasure of looking at the things I make, you know, I'm not trying to push buttons and I don't have a lot of social commentary, particularly, I don't mind making people think. I think the new show will make people think a little bit. And the family pictures made people think a little bit more than I really thought they were going to. If you were to look at the the product I think you would have to agree that at most of my work there's a great emphasis on beauty and invocation and sublimity of memory and loss and time and love and all that kind of stuff this is one would hope conjured up by this work. But it's hard to cough up a real philosophy behind the work I'm not even halfway done yet. What I'm looking for is an image that is pristine in its ability to evoke feelings from people.

On June 4, 1993, eight years into taking the pictures of my children, I wrote this to my friend Maria Hambourg:

«So, I have come to a quiet moment before my daily walk to meet the girls after school (surveillance and protection of children still in force) and I face the blue screen, trying to reconstruct what has happened since we sat at your dinner table.

«I’m stronger now, though I haven’t taken any new pictures, which is where my strength has usually come from. I am still afraid for the children, the boogeyman kind of fear that may not leave me until they have outgrown their present skins. And I’m still afraid that the good pictures won’t come, as usual.

«This year, though, the good pictures of the kids might not come. The fear may scare them off. My conviction and belief in the work was so unshakably strong for so many years, and my passion for making it was so undeniable. Now, it is no longer the same: I am frightened of the pictures, I am reluctant to push the limits. I suspect this work is dying its natural death: I sense fertile ground as I bury it, though, and a new kind of wisdom that comes with the acceptance of the limits I wanted to push for so long.»

The phenomenon of the last year spun me around and now leaves me wobbling, like a spent top, towards stasis. I am grateful for the peace that has finally begun to settle again in our lives: the phone calls are fewer, the list of sold prints within a year of being completed: I have the sense that I am getting control again. And I’m oh so much smarter now: I’ve had my 15 minutes and never has the sweet tedium of my life looked better.

The family pictures changed all our lives in ways we never could have predicted, in ways that affect us still. Their genesis was in simple exploration, at times of a documentary nature, at others conceptual or aesthetic and, in the best pictures, all at once. But the simplicity of intention and vision with which I began became complicated over time, by narrative, by defiance, by the natural evolution of an aesthetic, by doubt, and, yes, by fear.

Those pictures, rooted in our family’s domestic routines and our little postage stamp of native soil, had the unlikely effect of delivering the kind of overnight international celebrity that so many people, including many threadbare artists, desire. Clichés tell us that fame is a prize that burns the winner. The clichés are often right. As Adam Gopnik once remarked, when we hit pay dirt, we often find quicksand beneath it.

The wobbling-top analogy I used with Maria isn’t far off the mark; this brush with celebrity spun me near senseless. My refuge then, as it had been since childhood, was the farm, where within the sweet insularity of its boundaries I still find my equilibrium.

Never had I needed that equilibrium, the soothing balm of perfect proportion and beauty that I find on the farm, more than I did then. Most people who know me well, and even those who don’t but know my work, will eventually use the word “fearless” to describe who they think I am. Maybe it’s deserved, to a degree; certainly my horse-racing life qualifies, and sometimes, perhaps, my artistic life. But that mettle, the recklessness, self-possession, and hauteur — I know where that comes from.

I knew even in high school that I wanted to be an artist. That goes back to my parents and the acceptability ofbeing an artist in my family.

Part of my personality is that I was raised by a father who didn't allow disappointment. Whatever we did had to be done absolutely perfectly. It was a tacit demand. He never spoke it. He always just exemplified it. The thing about Daddy is, he was so courtly and so mannerly and so proper and so quiet. You would never know of his sort of eccentricities and idiosyncrasies and peculiarities. And he always looked like he had really important things on his mind. Yeah. l always thought he did. He was terrifying to us children, that's for sure. He was so remote. It's okay. I came out of it all right. I'm tough.

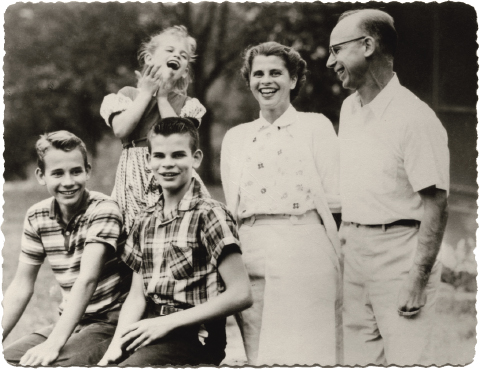

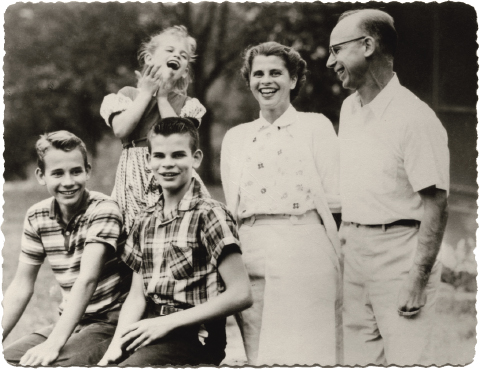

My father was a renegade Texan with an excellent northern education, an atheist, and an intellectual. He kept packs of big dogs, bought art (Kandinsky and Matisse in the 1930s, Twombly in the fifties) and drove fast foreign cars. As a southern family in the 1950s and sixties, we were simply different and we knew it.

He was an oddball, a character, an eccentric. To this day, he remains a paradox to us.

He was a physician who reminded me, even in his appearance, of the country doctor in W. Eugene Smith’s Life photo essay. But where that doctor wore a look of puzzled exhaustion, my father very often wore a look of impish certitude. Maintaining an often annoying system of compassionate ethics, he felt no conflict in the perceived contradiction of being both a moralist and an atheist. He was quiet and unassuming in his persona, and extravagant in his vision, his mannered and courtly behavior improbably paired with unapologetic self-indulgence. My mother’s frantic pleas fell on deaf ears as he routinely terrorized the family by driving 120 miles per hour in whatever was the fastest sports car made on any continent.

I know the pain of being different. I grew up with a pair of outspoken and visible parents. My father was the primary influence on my life. In our community his political beliefs, his commitment to the civil rights movement and his unabashed atheism were branded communists, and we children bore the brunt of other children's scorn. To make matters worse he was a complete oddball and as a child there was nothing I wanted so fervently as parents who belong to the country club and drove a wood sided station wagon and went to church.

As a family, we were simply different. My two brothers and I were the only children in our school required by our parents to sit in the hallways during Bible study. There was no wood-sided family station wagon, no membership in the country club, no church group, no colonial house in the new subdivision. Finally, we all came to believe what Rhett Butler told Scarlett: that reputation is something people with character can do without.

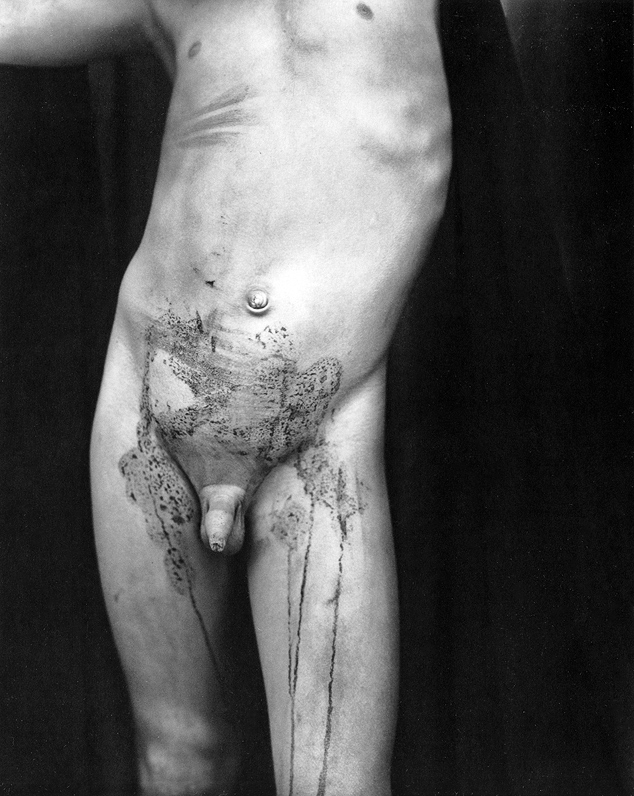

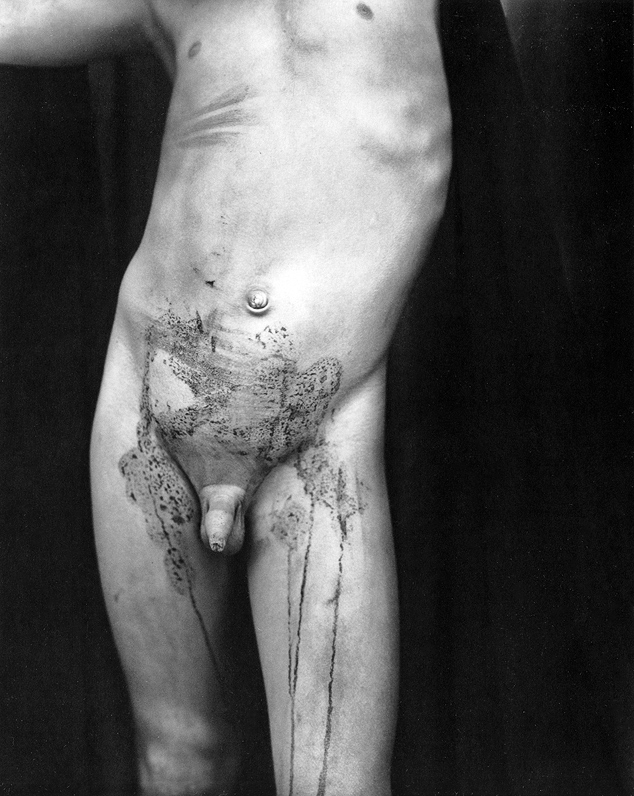

Other families had crèches at Christmas, but our living room had this decoration my father placed to my mother’s feigned mortification:

joined by Chastity the following year.

With Man Ray-like obsession, my father collected stuff and made singular art pieces late in the night in his workroom. He produced whimsical art from almost anything — this little snake, which once replaced an uninspired floral arrangement and was the centerpiece of the dining-room table, turned out to be a petrified dog turd:

On the morning that his gardens were open to the Virginia State Garden Tour (you remember how to pronounce garden, don’t you?), he put this sculpture on one of the back trails at the base of a big oak.

My father made a living as a country doctor but what he loved to do was make these weird sculptures. This is the kind of silly stuff he would do. He found a cedar tree trunk that had three branches that came out and each one of'em had a little sort of swelling on the end. So he did a little sanding and carving and cut it so that it looked exactly like a male torso with these three phalli coming out. His garden was on the garden tour and he put that out, sort of tucked away in some corner. And all the little women with their white gloves and hair were walking around. When my mother found out about it she just fell apart. It was her garden. It was open for the entire state of Virginia. And there was this thing. When my mother came upon it with her group of white-gloved ladies trilling with nervous laughter, she rued the day she’d fallen for that irreverent wag.

He called it Portnoy’s Triple Complaint. Portnoy’s Triple Complaint graced the backyard when his garden was on the state garden tour and after someone sent Philip Roth a photograph of it, Roth wrote back:

«I react with wonder and awe. None of us should complain, of course; art reminds us of that. Dr. Munger is a brave man to have such a thing in his garden. I would be tarred and feathered and thrown out of my town if I dared. Luckily people forgive me my books.»

But, while bodacious and impious, my father was also compassionate. He believed in socialized medicine, stating often that medical care is like education: everyone should have access to it. When the community doctors met and agreed to raise the rates for an office visit to seven dollars, Daddy lowered his to five. My mother, who at first kept his books, despaired of his refusal to charge those who could not afford to pay.

She once saw a patient who had not paid for the last several babies my father had delivered by lantern light at his remote home. The man was leaving the liquor store with an armload of bourbon as she was going in.

Indignantly she confronted my father about it at dinner that night and he responded flatly, “If you owed the doctor as much as that man owes me, you would want a drink, too.”

He had strongly held beliefs and was brave about asserting them. And he made us kids be brave, too, facing the little-understood challenges of civil rights, integration, and separation of church and state. During the early 1960s the schools we attended had daily Bible study and I was the only grade-school child who had to leave the classroom and sit outside the principal’s office while others studied Scripture. I can still remember the burning humiliation of having the younger students going single-file to lunch pointing and making fun of me. Never had I wanted more to be just like everyone else. But my father wouldn’t yield, and year after year I masked my mortification with indifferent cockiness.

Our family was considered fairly unconventional in our small-town Virginia community. My parents didn't support all the sort of middle-class things that everybody else's parents supported. That's what it came down to. Our family had no wood-sided station wagon. We didn't have a television. We didn't belong to the country club, no country club membership. We didn't go to church, and no colonial house in the new subdivision. We read the New York Times and used the sports pages to line the parakeet’s cage. I think my father came to believe long ago what Rhett Butler told Scarlett: reputation is something people with character can do without. And as a consequence, we were somehow different no matter how hard we tried to be normal. I wasn't an easy kid to raise. I'm not saying I was a bad seed, by any means but I think I was fairly headstrong, stubborn. It's all such a distant memory now since I'm such a different person.

I must say, we were totally intimidated by him. lt was part of that '50s thing where, Don't bother Daddy. Kind of that thing. But it was also just his personality. He really had some kind of peculiar power to him. And that was true right to the day he died. I remember, when he was sick, and he was standing back in the study and it took me all morning long, and I screwed up the courage to actually go over to him and I was gonna tell him I loved him, right? So I, like, walked up to him really quiet, and I said, Daddy? And he went, What? and I said, I love you. And he said, There, there. There, there, dear. Oh, I know this is an important moment in our relationship, and you know I'm dying and I know I'm dying, and you wanna say something really important to me. It was, There, there, dear. You'll get over it. Oh, man. But I said it. By God, I actually said, I, love you, Daddy. Yeah. Yep. Yep. Yeah.

Character and character building (other words, I guess, for sucking it up) were a big deal in our family. I have wondered whether my parents were right to expect me to suffer for a concept about which I lacked the maturity to form an opinion. Of course the fact that this parallels the situation of my own children, snickered at by their classmates for being in unconventional pictures, hasn’t escaped my notice. I think the lessons I learned from my father, as painful as they occasionally were, made me the character I am. I don’t regret them, especially as we could retreat to the farm, where who we were seemed normal.

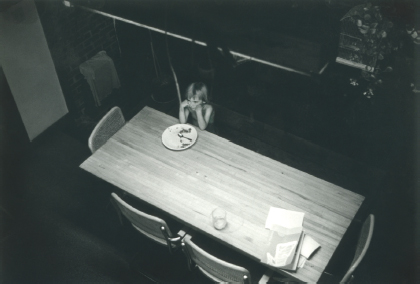

Even now, when I look at the arc of my work, those pictures taken on the farm and at the cabin seem more balanced, less culturally influenced and more universal, than those taken anywhere else — like this little honey of an image made years before I’d even identified my children as possible subjects.

Why it took me so long to find the abundant and untapped artistic wealth within family life, I don’t know. I took a few pictures with the 8 × 10 inch camera when Emmett was a baby, but for years I shot the under-appreciated and extraordinary domestic scenes of any mother’s life with the point-and-shoot.

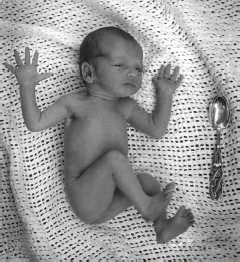

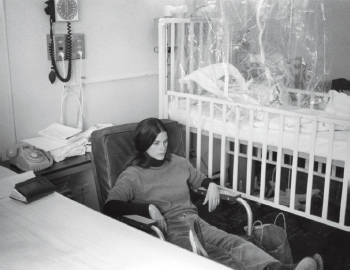

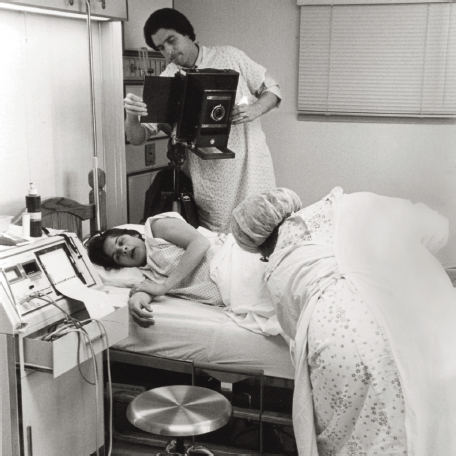

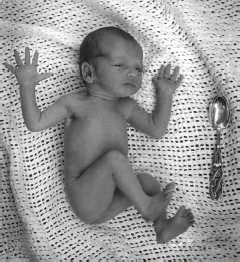

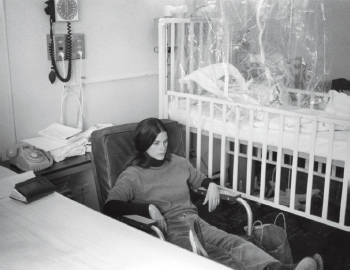

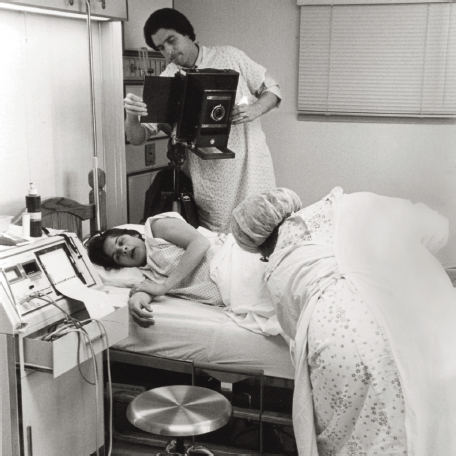

Like this one of my preemie Jessie, born in 1981, hardly bigger than the spoon with which I stirred my tea:

And her miraculous survival after countless bouts of pneumonia: Where was my camera then?

I missed so many opportunities, now tantalizingly fading away in the scrapbooks:

The puking,

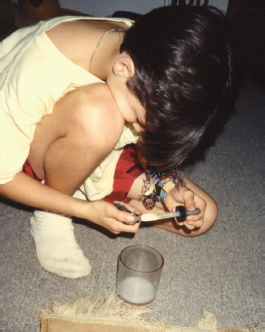

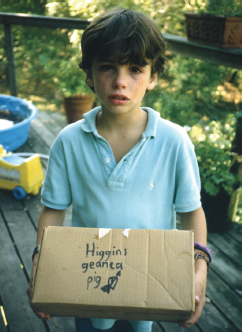

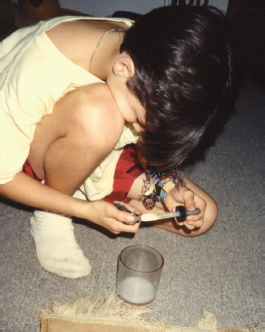

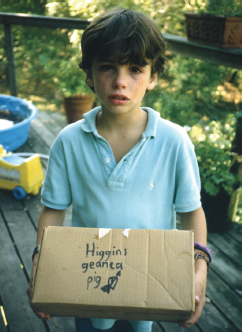

the pets:

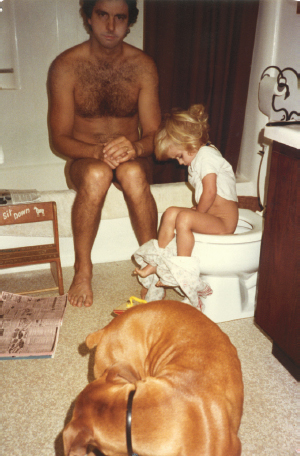

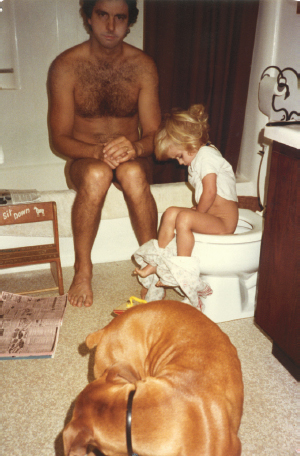

… and the toilet training, the never-ending toilet training.

Maybe at first I didn’t see those things as art because, with young babies in the house, you remove your “photography eyes,” as Linda Connor once called the sensibility that allows ecstatic vision. Maybe it was because the miraculous quotidian (oxymoronic as that phrase may seem) that is part of child rearing must often, for species survival, veil the intensely seeing eye.

I know for sure that the intensely seeing eye was different from the one I used to quarter thousands of school-lunch apples and braid miles of hair through my decades of motherhood. I had to promote this form of special vision and place myself, with deliberate foresight, on a collision course with felicitous, gift-giving Chance. I described this state in a 1987 letter:

«I am working, every day,… on new photographs. This body of work, family pictures, is beginning to take on a life of its own. Seldom, but memorably, there are times when my vision, even my hand, seems guided by, well, let’s say a muse. There is at that time an almost mystical rightness about the image: about the way the light is enfolding, the way the [kids’] eyes have taken on an almost frightening intensity, the way there is a sudden, almost outer-space-like, quiet.

«These moments nurture me through the reemergence into the quotidian… through the bill paying and the laundry and the shopping for soccer shoes, although I am finding that I am becoming increasingly distant, like I am somehow living full time in those moments.»

And again to Maria Hambourg in April 1989:

«Good photographs are gifts.… Taken for granted they don’t come. I set the camera up and… suspend myself in that familiar space about a foot above the ground where good photographs come. I wait there, breath suppressed, in that trance, that state of suspended animation, the moment before the frisson.…

«It has always worked before and the moment when it starts to come is unlike anything else: when it falls so perfectly into place and Jessie cocks her hip and doesn’t move out of the 1 inch of focus I have: when the wind blows up just the right little tracery in the water behind the alligator. That moment possesses such a feeling of transcendence: it’s the ecstatic time: better than sex. The parallels are all too obvious and can only be understood, I maintain, by a woman.»

But it wasn’t really until 1985 that I put on my photography eyes, and began to see the potential for serious imagery within the family. I began, as I often do, with a promising near miss, using the 8 × 10 view camera to photograph Virginia’s birth.

I had delivered both Emmett and Jessie without any drugs at all, damn near the hardest things I have ever done in my life. It was especially painful with the first child, Emmett, a relative porker at over six pounds, but easier with Jessie, who weighed in at only four pounds and change. Both were fairly fast deliveries, but with intense and unrelenting contractions that I barely managed with Lamaze breathing, Larry at my side. I figured I could do it one more time, and why not try a picture?

Two weeks before Virginia’s due date, I took my 8 × 10 to the birthing room and set it up, pressing into service as my stand-in a bewildered candy striper who lay on the bed in what we assumed would be my posture at delivery. I focused on her hands demurely pressing her skirt down between her legs, which were elevated in steel stirrups the way we gave birth back then. Leaving the camera bellows at exactly that extension, I removed the camera from the tripod, and bent over my balance-destroying belly to make grease-pencil circles on the floor where the tripod legs were. Then I packed up, carried the equipment to the car, and went home to wait it out.

I didn’t have long; my water broke in the early morning a week before my due date. I made the kids’ lunches, walked them to school as usual, and Larry went off to work. The pre-focused camera, tripod, and film were waiting in the car, so I drove to the hospital, hauling my leaking bulk, plus the equipment, down the corridors to the OB floor. More accustomed to seeing a woman in labor carrying a floral overnight bag, the nurse on duty jumped up to help me in.

I was uncomfortable and it took more time than it should for me to get the camera set up on the black marks, insert the film holder, and do a quick light-meter reading, taking into account the wall of sun-filled glass into which I would be shooting. At noon my redheaded nurse, Mrs. Fix, was supposed to leave for her thirty-minute lunch break, but she eyed me, lying under the view camera, blowing and glassy-eyed with pain, and announced that she was calling Larry and the doctor right then. To hell with lunch.

Larry got there first. I was in labor delirium by then, breathing fiercely and speechless with hard contractions. At 12:30 I saw Dr. Harralson’s white coat come flapping up the hill outside the windows and suddenly the room was filled with activity. Trying not to push, I signaled Larry to take the black slide out of the film holder and cock the shutter at the pre-set speed. He knew not to let the camera move an iota in that process, which is harder than you might think with shaking hands.

Larry: «The thing that people need to realize when they think about these kids getting photographed as much as they are is that they've been photographed from not only day one but from the moment of birth and actually in the case of Virginia the moment of birth. Sally actually had the 8 by 10 cameras set up next to the bed (it was a birthing room) and was able to snap a picture just as Virginia was born. So I mean these kids have been photographed. It's part of their life, it's almost like having a film, it's there, it's part of what you're doing, it's running basically, it's... you may hear the click and may register the fact that a photographs been taken but usually you're not self-conscious about it because it's just so much a part of what we do.»

At 12:37 the baby crowned and I reached up to the camera, thinking, “Dammit, Lois Conner gave me a shutter release and if ever there was a time for one, this is it. How could I have forgotten it?”

But it wasn’t camera shake from my fitful finger on the shutter that made the resulting image not all that interesting. I had correctly figured that Dr. Harralson’s body would block the light from the windows so I’d have to use a slower shutter speed. Anticipating the likely light levels, I had calculated the aperture at f/4.5, wide-open, for a fifth of a second, and I was right.

But at such a slow speed, the barreling baby was blurred as she slid out.

The picture was a dud.

But… maybe not a total loss. Perhaps, in hindsight, it was the birth of the family pictures, breathing life into the notion that photographs, and sometimes good ones, could be made everywhere, even in the most seemingly commonplace or fraught moments.

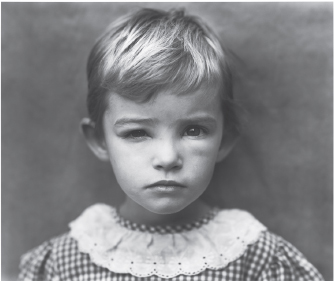

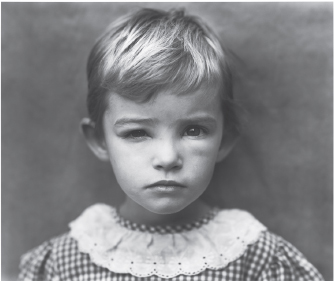

A few months later, while I was working on the 12 year olds and I had by that time two children, toward the end of the 12 year old series, I took what I think of as my first good family picture. It was of Jessie’s face, swollen with hives from insect bites, to which she is especially sensitive. One day Jesse came home with us gnat bite on her face and it was all swollen up and actually it had bruised, it really looked like she's been beaten up, she was so striking that it occurred to me that right here, right under my nose was a was a picture, I mean a real picture. It was so powerful, it just begged for a new camera, to take it up. This was the one I started with, when she showed up that afternoon:

Up until that point I thought that the children were snapshot material so that's how I started. But she was so striking that it occurred to me that right here, right under my nose was a picture — I mean, a real picture. As soon as I had that realization that there was art right under my nose that I was missing, I started seeing things differently. And I would photograph both things that happened and I would set things out. I really wasn't trying to push anybody's buttons. I just was responding to things that appealed to me.

Looking at this picture now, I realize it is just a continuation of the soft, gauzy still lifes of flower petals and chiffon I had been working on for years, except this one had a kid in it.

I had done some earlier abstracts of Emmett with the same idea, chiffon, flowers,

but, in the chiffony picture of Jessie, I sensed a new direction. I don’t know if I’m all that different from other people, but for me great artistic leaps forward are not accompanied by thunderclaps of recognition. In truth, they aren’t even usually great leaps. They are tentative toe testings accompanied by an ever-present whisper of doubt.

Despite that whisper, I went ahead and took another picture of Jessie that day, which I called “Damaged Child.”

I just put her up against the wall and documented it. So that's how I started.

As soon as I printed it, I noticed its kinship with the familiar Dorothea Lange picture “Damaged Child, Shacktown.”

In both, the girls have a look of battered defiance. Just in case anyone could miss it, I made sure that the title drove the comparison home.

As strange as it sounds, I found something comforting about this disturbing picture. Looking at the still-damp contact print, and then looking at Jessie, completely recovered and twirling around the house in her pink tutu, I realized the image inoculated me to a possible reality that I might not henceforth have to suffer. Maybe this could be an escape from the manifold terrors of child rearing, an apotropaic protection: stare them straight in the face but at a remove — on paper, in a photograph. So I started working with the children, they didn't seem to mind.

Virginia and the Sun is an example of putting Virginia under a little bit of cloth netting but gave it a really eerie effect.

With the camera, I began to take on disease and accidents of every kind, magnifying common impetigo into leprosy, skin wrinkles into whip marks, simple bruises into hemorrhagic fever. Even when a scary situation turned out benign, I replayed it for the camera with the worst possible outcome, as if to put the quietus on its ever reoccurring.

Once at about age five, Jessie took a mind to hop across the creek on the big rocks with which we’d dammed it, and walk the half mile or so to Emmett’s school. I was a pretty vigilant mother and had glanced out the window to see her, just a moment before, playing with her doll Maria on the tire swing, but suddenly I looked down at the bottomland and… no Jessie. Being the hysteric and fatalist that I am, I went into full panic mode, calling and running up and down the creek banks. By this time, Jessie was long gone, carefully looking both ways as she carried Maria across the nearby street on her way to Waddell School. I called the neighbors and my friends, and pretty soon we had a group of searchers fanning out into the woods. I stuck to the creek edge, certain I’d see a flash of gingham, of white sock and patent leather Mary Janes in the water.

Before long, the school secretary showed up with a beaming Jessie, and I sank into the bone-deep exhaustion of relief. The next day I set up the camera, cajoled seven-year-old Emmett into putting on a dress, and made this picture, almost too awful to look at, even now. I called it “The Day Jessie Got Lost” and I prayed it would protect us from any such sight, ever.

In fact, it didn’t.

A short time later, on a hot afternoon in early September 1987, I walked to the road at the top of our driveway to meet Emmett, who was on his way home from playing with a friend. That crossing was then especially busy because of nearby construction, and I always went up there to help the kids get across. An idling bulldozer blocked my sightline, but I spotted Emmett as he approached the road where a flagman was holding back oncoming traffic. Emmett paused on the other side of the street by the bulldozer.

The noise it was making was such that I couldn’t yell to him to wait, so instead I held up my hand, palm forward, in the universal “stop” sign. Not schooled in international hand gestures, Emmett mistook it for a “come to me in a hurry” sign and did just that. A second before he sprang forward, the flagman signaled the impatiently waiting cars to come ahead. The first car in the queue was a 1970s Chevelle, a heavy, powerful car driven by a seventeen-year-old who was only too willing to oblige the flagman’s command. He didn’t exactly gun it, but he wasn’t going to miss the opportunity to show the workmen lining both sides of the road what his car could do.

The poor kid couldn’t possibly have braked to avoid Emmett, who had leapt out from his side of the road, his happy eyes on mine. The car, going about thirty-five miles per hour, caught him midleap. Emmett’s head slammed into the hood and he was catapulted more than forty feet, where he lay crumpled and bleeding in the middle of the road.

Of course nobody had cell phones then, but even if they had, everyone who witnessed this seemed frozen in place. I screamed for someone to call the rescue squad, and no one moved, so I ran back down to the house and did it myself, worrying that while I was gone another car might hit Emmett. Then I ran back up the driveway and down along the forty-seven feet of skid marks to the splayed figure in the road.

I have said many times that the image of Emmett lying there is burned in my mind, but that is not true. In fact, I can’t tell you what he was wearing without consulting the photographs I took later in the hospital or even exactly how he had fallen. I remember lying in the sticky tar, I remember seeing the figures of the workmen in their hard hats standing on the hill above us, silent like a herd of curious bovines, and I remember knowing not to move the body. I also remember that I thought about photography in the eleven minutes it took for the first-aid crew to arrive.

When they did, Emmett was semiconscious, and when he was asked what his name was he spelled it out in a steady voice: E-M-M-E-T-T.

A glimmer of hope.

A few days after the accident came a knock on my door. Several of the workmen were standing there, yellow hard hats tucked under their elbows, one with a rose wrapped in cellophane from a convenience store. They stammered out their condolences and I then realized that they thought Emmett was dead from the minute they saw him hit. How could he not have been? That was why they never moved.

I thought he was dead, too. Seeing the Chevelle a few days later only reinforced the miracle of his survival. The still-shaken kid who had hit him drove the car over to our house and to demonstate the toughness of its metal suggested that Larry hit the hood as hard as he could. So Larry summoned up all his blacksmithing muscles and slammed his fist into the hood. Nothing.

Where Emmett had hit was a stomach-turning, head-sized dent.

After having made that dent and been catapulted down the road, Emmett, other than some vomiting and general pain, was found to be unharmed and was released from the hospital after just a few days. It is generally thought that what saved his life was that he was in midleap, airborne when he was hit, but who knows? To me, and I am sure to all of those who saw it, it is still inexplicable.

So in those eleven minutes, what was it about photography that I was thinking? Here’s what I wrote to a friend a month later, in October 1987:

But now, the real image of Emmett lying in a pool of blood has come to make the family pictures seem, ummm, trivial to me.

I lay there certain that his life was ebbing from his unconscious form and thought about… the real meaning of photographing my children. About whether I actually could have brought myself to photograph what is now so horribly burned into my mind. About what kind of photographer I really am… who exhorts her students to “photograph what is important to you, what is closest to you, photograph the great events of your life, and let your photography live with your reality” but who is paralyzed by that very reality. I actually wondered as I lay there, with my dying son, (or so I thought) if I could even hold a camera up. And, of course, there was no way. I am just not that kind of photographer.

I thought during that eleven-minute eternity that the world of motherhood is a far more complex thing than you and I ever imagined when we plunged so willingly into it, and that the fear and… joy I have encountered have staggered me.

How I love those children.

And how much I fear for them. And how real those fears can become, in just an instant. Right before my eyes, even, my horrified eyes. And, what’s worse is that I had imagined that scene, imagined it countless, terrible times and shaken myself out of it.

That is what those photographs were and now, of course, I am afraid of them. Afraid that by photographing my fears I might be closer to actually seeing them, not the other way round. Irrational, I know, but Emmett’s accident has turned a woman who lived on the edge into one who slips periodically into the depths and is only retrieved by a thread.

So, I have reached some sort of emotional impasse, I suppose, with these pictures. These last few weeks the new ones are suffused with the late summer light and they are gentler, more Southern, perhaps. I know all this will pass and that the image of him will stop arising, unbidden, to my mind and that the photographs will work themselves out. But it often is quite hard to reconcile one’s work with one’s life, isn’t it?

I had tried to exorcise the trauma of the experience by following my own commandment to “photograph what is important, what is closest to you, photograph the great events of your life.” I had taken my view camera into the hospital the night of the accident, but got nothing special there.

Then, a few weeks later I tried to make a photograph of the way Emmett looked when he was hit, or the way I felt he looked.

No go.

Emmett: «It's almost like she sees something happening and she just thinks to herself, I know that this is special, what I'm seeing right here. She sees something that she just doesn't want to forget.»

Emmett was completely recovered within a week, but I was still grievously wounded. I couldn’t shake from my memory the image of his sunlit, smiling face as he sprang toward me. And each time it came to me, I would suffer the sickening realization of the inevitable, the unstoppable that played out in that interminable split second. I would wake gasping and weeping from dreams, my concrete legs refusing the bidding of my panicked brain, horrified eyes turned to marble.

I tried a self-portrait. Another loser.

At the farm, the honeyed September light and the lazy, limpid river offered, as always, the cure, the balm for my bunged-up soul. At the farm, there is no reason for photography-as-inoculation, no fear and no danger. Just the land and the river and the sheltering cliffs, the comfort of the colossal trees.

Still, and not surprisingly, I concentrated on Emmett.

Emmett: «When I was young and Mom would get the idea to take a picture, you knew it was coming on and you'd better make yourself scarce or else you were gonna be in a picture. I mean, she would just get this look like she saw something we were doing that really struck her as being poignant and she had to have it.»

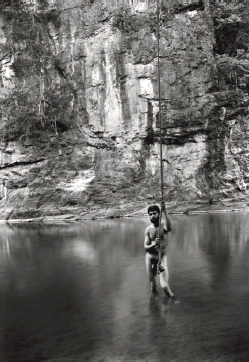

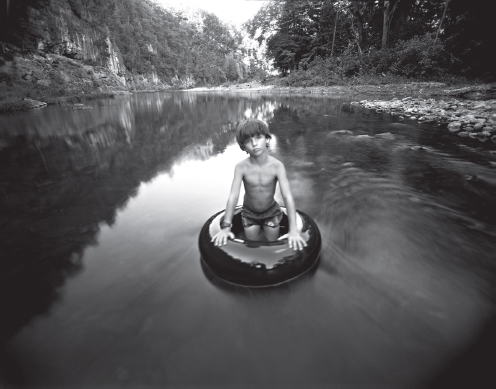

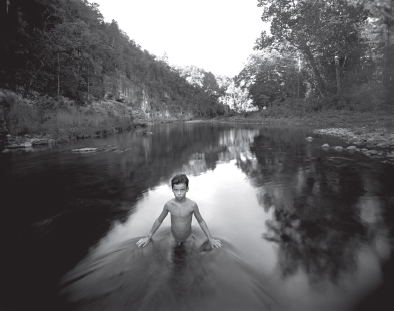

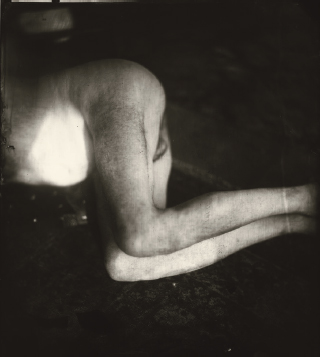

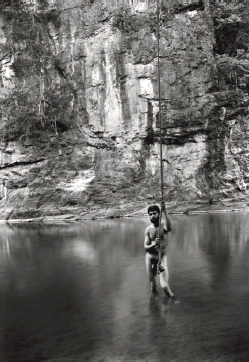

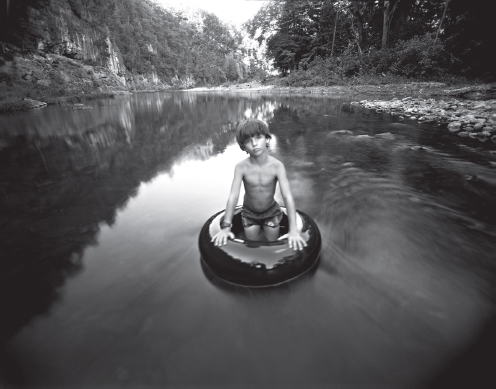

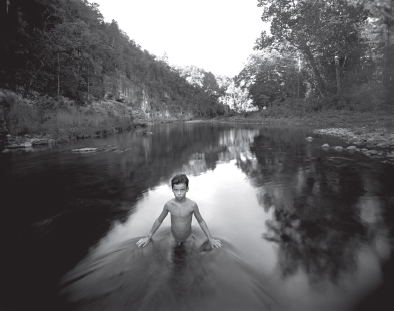

In each of these three pictures I saw something I liked: in the first, the solitary figure of the boy, in the next, the rush of water, made satiny by the slow shutter speed, and in the third, the V of the sky and the river.

Terrier that I am, at least in the pursuit of an elusive picture, I set out to marry all those features in one image, hauling the 8 × 10 camera and heavy tripod out into the river, slipping on the rocks, buffeted by the current, to set up in the riffling water at the lower rapids.

I somehow managed to cut out the sky part of the picture in the next try, but still saw the potential for a good image.

Maybe lose the snorkel, I decided.

Emmett: «The Last Time Emmett Modeled Nude was when mama need to take a picture and we were at my cabin. One summer mom took her camera out into the water and she just took pictures of me. I was just starting to become modest and I didn't I was like a little like that about taking my clothes off but I liked it because my expression captures what I was doing, I was cold and I was tired taking pictures and I was pretty grim and so my expression really took that as well.»

Now that I was on the scent, I was obsessed with getting this damn picture right.

Day after day that balmy September I carried the camera and one film holder to the middle of the river across the mossy rocks. The water was waist-deep where I set up for the picture, with treacherous drop-offs into dark, fishy holes.

After shooting the two sheets of film in each holder, I would swim, the holder high above my head, and get another, while dear, patient Emmett waited. I had six film holders, so we’d generally take twelve negatives each day — and most of them were failures.

They failed in many ways, sometimes because my wet fingers ruined the film, once when I dropped the film holder in the river, once because a flotilla of canoes came through, but usually because of dumb compositional mistakes on my part.

In this one he’s too far out of the water,

then here there’s too much light on the trees behind him,

plus he’s too far back, but I liked the satiny water.

Off-center here and don’t like those clouds, or his hair.

Damn light-meter strap in the way here:

But now we’re getting closer, got the hands right, still too far out of the water and the light is too bright behind him…

Okay, the hands are almost right here, but an awkward stance, still not a keeper.

Emmett: «You know, my mother's vision, she had an idea, it was almost like a dream. I think she has a dream picture, and she just gradually, like, refines it until it's exactly what she's looking for. It took like five separate trips out here, and taking, probably, looked like 15 to 20 pictures every single time. She was looking, every time she took a picture of me, I knew she was looking for that intensity that I feel my sisters and I have, my mother has — it's just like this intensity, Mann intensity, I don't know what it is, it plagues me to this day.»

I have to say, it's unfortunate how many of my pictures do depend on some technical error. It's not something I do to the negatives but on the other hand it's not a negative that I toss in the trash bin either. I've taken some pictures in the past that were miraculously transformed by some hand other than my own and made a better image. And I really welcome those interventions. Proust once wrote that what he prayed for in his work was the angel of certainty. But I'm sort of praying for the angel of uncertainty to visit my plate.

Another one...

Then, eureka.

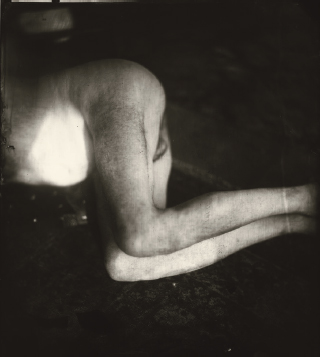

The Last Time Emmett Modeled Nude

Until you actually set up the camera — it's so funny — you don't see the picture until you commit the camera to it. And then suddenly something that was just a feeling turns into a photograph. It's the oddest phenomenon.

Seven different days we had tried, maybe eight — but I knew we had it at last. No one was more relieved than Emmett, who had given up all those afternoons to the demands of the light — and of his mother. Children cannot be forced to make pictures like these: mine gave them to me. Every picture represents a gesture of such generosity and faith that I, in turn, felt obliged to repay them by making the best, most enduring images that I could. The children, picture after picture, had given of themselves when the dark slide was pulled, firing off a deadly accurate look into the lens; a glare, a squinty-eyed look, a sad expression, whatever I asked for, as professional as any actor. And in many cases, they did this while hot, hungry, tired, or, like Emmett, shaking with cold.

It was not unreasonable when he announced that it was the last damn time he would model in the freezing river (by then it was October), and for some reason I titled the picture “The Last Time Emmett Modeled Nude,” although I knew the nudity was completely beside the point. That certainly came back to bite me in the ass.

Not every picture required this Herculean kind of effort, but more than a few did. When I sensed that a good picture lurked just beyond my range of vision, I went after it with dogged intent. I’d get a whiff of a good one in an odd snapshotty picture, like this one of Virginia about to dive off the cliffs,

and after considerable effort and multiple tries, finally got it right:

Virginia: «She would call us her models, but usually it was just something where she'd say "freeze," and we'd stop what we were doing. Sometimes she'd make some small alteration, but that was all. The one where my hair is on my ribs, I remember that I had to keep going back and wetting my hair, because it would dry and then slip so. That's the only thing that I remember.»

Do you remember how many times we took that picture? That was a production, because someone had to sit behind you in the river and thwack the river with the canoe to make those little ripples that are behind you. Yeah, Larry were thwacking the river, and she was standing there keeping her hair from falling off her ribs. And still maintaining a beatific expression. That was a really hard picture to take.

I wanted those family pictures to look effortless. I wanted them to look like snapshots. There is something about the whole 8 x 10 business. The sort of reverence that goes along with it, that you have to, you have to pay your dues to the photo gods, I guess.

That’s the way many of these pictures evolved, their genesis in a failed image but one that had some rudiment of the eternal in it — like the hair plastered across the ribs, or the V of sky and river with Emmett.

But others came completely spontaneously; the camera was almost always set up off to the side and when something interesting happened, I would ask for everyone to hold still, maybe quickly tweak something, and then shoot.

I wrote about it in a letter back then:

«You wait for your eye to sort of “turn on,” for the elements to fall into place and that ineffable rush to occur, a feeling of exultation when you look through that ground glass, counting ever so slowly, clenching teeth and whispering to Jessie to holdstillholdstillholdstill and just knowing that it will be good, that it is true. Like the one true sentence that Hemingway writes about in A Moveable Feast, that incubating purity and grace that happens, sometimes, when all the parts come together.

«And these pictures have come quickly, in a rush… like some urgent bodily demand. They have been obvious, they have been right there to be taken, almost like celestial gifts.»

Gifts, indeed. Many pictures came to me in that lucky rush of exultation, the ones for which I had time to shoot only one, one sheet of film, those where I sank to my knees after shakily replacing the dark slide, eyes shut tight in thanksgiving and fear, fear that I’d screw it up in the developer, fear that the fraction of a second I saw was not the one on film, and in exhaustion, too, from the breath-bated moment, a tenth of a second with the expansive, vertiginous properties of Nabokovian timelessness, while before me the brilliant angel no longer radiant with the sun snatches up the towel and heads to the beach, the tomatoes are imperfectly carved up for supper, and my heart, my pounding heart, sends from my core the bright strength for me to rise.

This, I think, it's the best picture I've ever taken in my life. It's called The Perfect Tomato and, again, it's a snapshot.

The Perfect Tomato.

I was photographing something else I can't even remember and the camera was just set up next to the table and Jessie was dancing, was doing like her ballet on the railing behind her and she stepped from the railing on to the table and that wonderful gesture and Virginia's mouth is open and wonder and she's just doing that little dance and the sun is behind her and I got the picture. And I'm more proud of that picture than anything I've ever taken and, I think, I really loved it. This to me is one of the most angelic ethereal pictures I've ever taken, it doesn't even deal with the body, it deals with some transformation into spiritual things.

Jessie: «In the picture of The Perfect Tomato I was dancing around them, the little, um, banister out at the cabin and I am turned into a pose like this and my mom just told me to freeze like this for just hold it, don't move at all, don't move a muscle, so I didn't move and my mom took the picture. But she didn't want to waste time because the sun was just right and everything was perfect so she didn't have enough time to focus so she just went ahead and took the picture. And when it was printed, well, you know, the only thing that was in focus was the tomato, so she called it The Perfect Tomato and it also looked like I had stepped down from heaven and bless that tomato.»

You can interpret those pictures any way you want. That's what gives them a lot of their power. And if you choose to interpret them as clear examples of child abuse and miserable depravity, well, you know, I can't debate, unless I'm there.

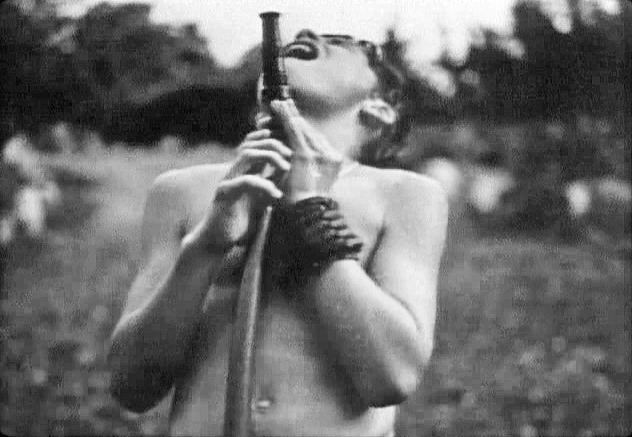

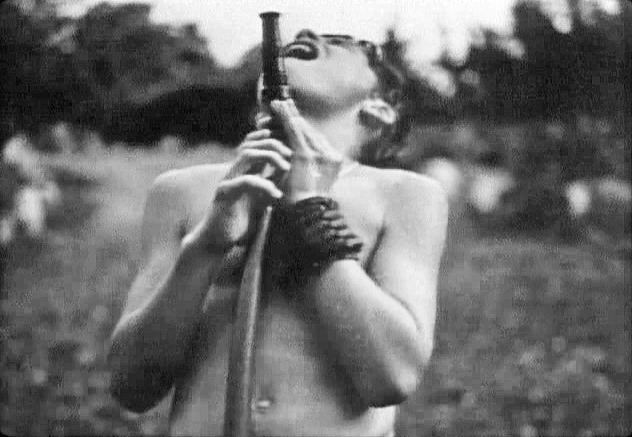

Maria Hambourg, Curator of Photography Metropolitan Museum of Art: «It the content of the picture is precisely what you see. For example in the picture like this one of Emmett with a hose what you have is a boy with a garden hose, he's clearly enjoying this marvelous freedom and this sense of elation of standing underneath this jet of water at the same time there's no doubt that this hose is like a snake but it's also phallic and so there's there's several layers of a reverberating meaning. I think that Sally's work suggests that there may be something much more pervasive that most of us ignore, which is a kind of sensuality and sexuality amongst all people.»

I've been asked if if it's cheating somehow to pose the pictures. And my response is unequivocally no, it's not cheating at all. In order to get the pictures that I get, that carry the weight that they do, they often have to be post. Things like that just don't happen quite that way. Most of these pictures are true to their life, to a large extent. I mean, they dress up, they dance on the picnic table, they lie in their father's arms the often the mood or the feeling or the pose, itself is absolutely real.

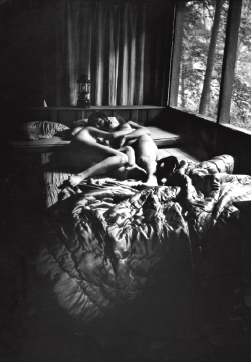

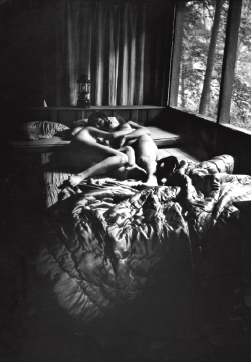

These are photographs of my children living their lives here too. Many of these pictures are intimate, some are fictions and some are fantastic, but most are of ordinary things every mother has seen — a wet bed, a bloody nose, candy cigarettes. They dress up, they pout and posture, they paint their bodies, they dive like otters in the dark river.

This one called Emmett's Bloody Nose and that's the one that drives people nuts, they look at that and they say, why are you taking a photograph of a child with a bloody nose, why aren't you? You know, I came bracing him to your maternal breast, why aren't you making sure that he, you know, is getting medical attention? Well, when a child walks in with a bloody nose that's so old, that it's like hardened chocolate on their face and he's perfectly fine, didn't you take a picture of it? So I've done that in the past and I've gotten some I've been people who were concerned I've gotten in some trouble for it, but you know I have to answer to myself and I know what happened.

Virginia: «I think what makes Mom different is that she can look at the same object that I would consider commonplace and ordinary but she'll make a print of it and suddenly I see the beauty of it.»

Taking pictures deepens the transaction between me and family members that I photograph and it in a certain sense can complicate it a little bit but I feel that it also strengthened it a great deal as we were putting the work together over the years. They would say, “Oh I don't want that one in, you know, I look stupid” or they've refined their vision and their way of seeing how photographs work. So in a certain sense doing that work raised my stock with my family. There's no way that I can get the pictures I do without the children working their particular magic in the picture either by the way they shift their weight or by the expression they give or just look, just some small gestural thing that becomes the punctum of the image. You don't get pictures like that with expressions like that, you can't force someone to do that, they have to give you the picture, there's injury and there's pain and there's anger and there's resentment in their faces and there's, you know, pouting and there's the runs the gamut... Yeah, I certainly wanted to include all of that as well as happy moments but family life is of course, this we all know, far more complex than it's usually portrayed.

They have been involved in the creative process since infancy. At times, it is difficult to say exactly who makes the pictures. Some are gifts to me from my children: gifts that come in a moment as fleeting as the touch of an angel’s wing. I pray for that angel to come to us when I set the camera up, knowing that there is not one good picture in five hot acres. We put ourselves into a state of grace we hope is deserving of reward, and it is a state of grace with the Angel of Chance.

When the good pictures come, we hope they tell truths, but truths “told slant,” just as Emily Dickinson commanded. We are spinning a story of what it is to grow up. It is a complicated story and sometimes we try to take on the grand themes: anger, love, death, sensuality, and beauty. But we tell it all without fear and without shame.

Memory is the primary instrument, the inexhaustible nutrient source; these photographs open doors into the past but they also allow a look into the future. In Samuel Beckett’s Endgame, Hamm tells a story about visiting a madman in his cell. Hamm dragged him to the window and exhorted: “Look! There! All that rising corn! And there! Look! The sails of the herring fleet! All that loveliness!” But the madman turned away. All he’d seen were ashes.

There’s the paradox: we see the beauty and we see the dark side of things; the cornfields and the full sails, but the ashes, as well. The Japanese have a word for this dual perception: mono no aware. It means something like “beauty tinged with sadness.” How is it that we must hold what we love tight to us, against our very bones, knowing we must also, when the time comes, let it go?

For me, those pointed lessons of impermanence are softened by the unchanging scape of my life, the durable realities. This conflict produces an odd kind of vitality, just as the madman’s despair reveals a beguiling discovery. I find contained within the vertiginous deceit of time its vexing opportunities and sweet human persistence.

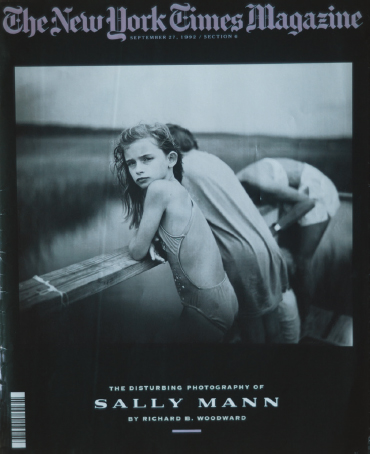

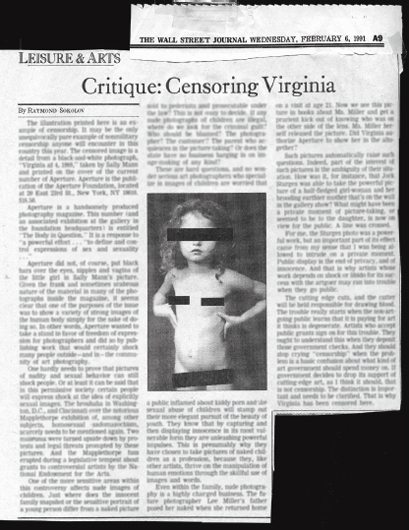

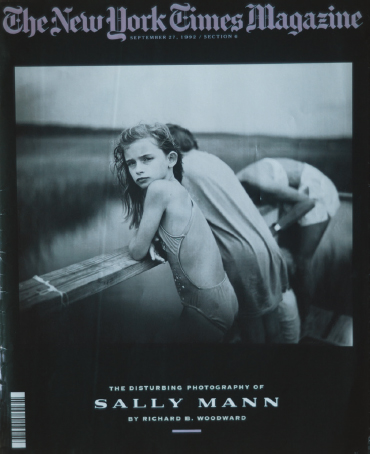

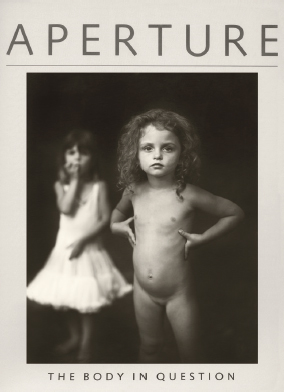

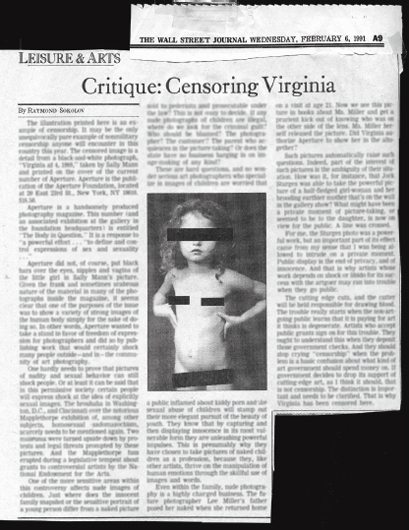

I think what I realized is that I had children who had, as individuals extremely potent personalities. From the minute I took those first 10 pictures, I knew they were good pictures. Lots of people take good pictures, and they don't sell 'em, don't get famous and they don't get on the cover of The New York Times Magazine. But at the very least I knew they were strong pictures that hadn't been done before. At the same time I was building up this body of work there was this outrage in the religious and right-wing community against child pornography and they finally just collided. l think the work just became a victim of that hysteria. It may be that the controversy had the inarguably beneficial effect of bringing the work to the public consciousness. I think a lot more people saw the work as a consequence. Do people buy prints because they're controversial? Do they buy prints because they've seen them and they like 'em? I like to think it's the latter, but they did buy them. I don't know. I just have real mixed feelings about what happened during that time. I mean, if I could do it over in some way I would not wish for that kind of backdoor celebrity. It brought my name to the public but I think good work eventually gets to the public anyway.

In this confluence of past and future, reality and symbol, are Emmett, Jessie, and Virginia. Their strength and confidence, there to be seen in their eyes, are compelling — for nothing is so seductive as a gift casually possessed. They are substantial; their green present is irreducibly complex. The withering perspective of the past, the predictable treacheries of the future; for the moment, those familiar complications of time all play harmlessly around them as dancing shadows beneath the great oak.

Ubi Amor, Ibi Oculus Est

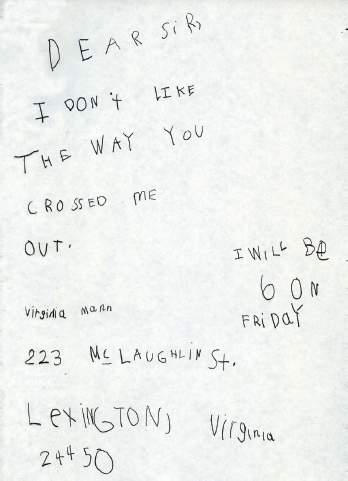

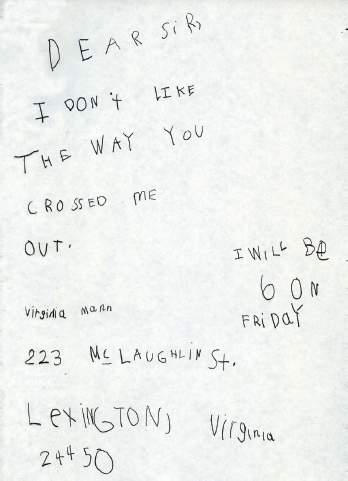

Remember that the file for the Mann murder-suicide was not deep in cold-case storage at the New Canaan police station? And that after thirty-five years it was sitting out on the desk in the records office when I asked for a copy? Wonder why? It’s a strange story that speaks to the hazards of public exposure, which in turn illustrates what ultimately was for me the most chilling aspect of showing and publishing the family pictures.

In 2010 anonymous letters began arriving at a variety of places — mailboxes of art critics, museum and gallery directors, college presidents, art professors, book publishers, collectors, newspaper offices, and, to the point of this particular narrative, the chief of the New Canaan Police Department, the head of the state police, and the attorney general of Connecticut.

The letters raved, in varying degrees of readability, that I had made my career by appropriating the work of an underappreciated and unnamed Virginia artist and that I was a fraud, a liar, a thief, and a murderer. Almost all were postmarked Richmond, Virginia, and typed on a computer, including the address labels. At first they were merely an annoyance to me and to those who received them, but as years went by and it grew clear they came from a committed and possibly deranged stalker, I became alarmed.

Various law enforcement authorities in Connecticut were also alarmed. Here is one of the letters they received, with redundant passages excised:

«This letter is concerning the July 1977 case of Dr. Warren Mann and his wife Rose-Marie Mann in New Canaan, CT that was listed as a murder-suicide. I have come across some recent information that I believe is extremely important that could prove it was not a murder-suicide but indeed a double homicide. The culprits being Larry Mann the oldest son of Warren and Rose-Marie and Larry’s wife the controversial photographer Sally (Munger) Mann.

«Someone needs to check if Larry Mann was born having Arthur as his middle name. Arthur is what he uses as his middle name and it makes sense considering his father was Warren Arthur Mann. If so, we need to ask the question what the “TE” stands for in Laurence TE Mann, one of his aliases.

«Logically with Larry Mann being a philosophy major in college and with what happened to Warren and Rose-Marie Mann Larry is taking the TE Mann as Teman, grandson of Esau from the bible, a.k.a. descendent of Esau. Larry Mann is relating himself as Esau and his brother as Jacob.

«One of Larry Mann’s other aliases Laurence A. Mannba a.k.a. Larry Mamba is a bold statement in itself. Esau was known to represent the hunter and bloodshed, he was the man known to have the love of violence and murder. Mamba — the deadly snake. Larry Mann, like his wife Sally, receives a natural buzz taunting the law to see how far he can go without being caught. The aliases would help him achieve this high.

«If Sally’s father Dr. Robert Munger or any Munger was used as alibis for Sally and Larry Mann’s whereabouts at the time of Warren and Rose-Marie’s death it would be a drastic mistake.

«Dr. Munger is known as the devil in human skin and he would do anything to help his daughter continue the chain of destruction to destroy anyone and anything of goodness. He was known to make his extra money as the abortionist in the area when it was illegal.

«Sally Mann hates Catholics and tries to set them up anytime she can. Someone needs to check if Rose-Marie Mann grew up Catholic since Sally and Larry chose to set up Rose-Marie during the crime scene. There is some crucial reason they chose Rose-Marie.

«Rose-Marie and Warren Mann have been deceased now for over 34 years. Rose-Marie is innocent and she cannot speak in her defense about what really happened that July of 1977. Sally Mann has finally made the mistake to prove that she and her husband Larry Mann were responsible for a double murder.

«It is time to clear Rose-Marie’s name so she and her husband Warren can both rest in peace.»

(The end of the letter noted that copies were sent to the FBI resident agency in Bridgeport, to the New Canaan police, to the Connecticut State Police, to various named public officials, and to a journalist at The Hour newspaper in Norwalk.)

Crazy as these letters seemed, the authorities who received them couldn’t ignore what they were claiming. Late in 2011, unbeknownst to us, the New Canaan police reopened the case of the murder-suicide of Warren and Rose Marie Mann. At the same time, a capable detective for the Rockbridge County Sheriff’s Department, Tim Hickman, began a local investigation into the origin of the letters, and proposed a long-shot request for help from the FBI at Quantico, Virginia.

The FBI has bigger fish to fry than a disgruntled would-be artist on a letter-writing campaign. It gets thousands of requests for help from local law enforcement nationwide and takes only a handful, so we were surprised when the Threat Assessment Unit agreed to meet Hickman at Quantico. They put several agents on the case and, together with Hickman, worked up a profile. It was a relief that they believed the immediate physical threat to me was minimal, but all the same the letters were getting crazier and more frequent. I worried when I appeared in public for speaking engagements or openings, and even found the seclusion of my life on the farm, which had always offered me protection and comfort, becoming a source of disquiet.

In the end, Hickman’s open ears and old-fashioned gumshoe investigation cracked the case. The fruit bat letter writer was exactly the person the FBI profile suggested she’d be: older with an unsuccessful artist-daughter who lived at home, but (the Threat Assessment Unit got this one wrong) she also had a history of instability and physical violence. Once local law enforcement and the FBI confronted and strenuously warned her off in spring of 2012, the letters stopped.

Even now, writing this a year later, I still feel vulnerable and exposed, and I am even more mistrustful of our culture’s cult of celebrity. Of the many unexpected repercussions surrounding the exhibition and publication of the family pictures, the widespread public attention and our seeming accessibility are still the most disturbing to me.

Looking back on that tumultuous decade, during which the skirmishes of the culture wars spilled into my territory, I have come to appreciate the dialog that took place, but at the time I occasionally felt that my soul had been exposed to critics who took pleasure in poking it with a stick. Many people expressed opinions, usually in earnest good faith but sometimes with rancor, about the pictures: my right to take them, especially my right as a mother, my state of emotional health, the implications for the children, and the pictures’ effect on the viewer. I was blindsided by the controversy, protected, I thought, by my relative obscurity and geographic isolation, and was initially unprepared to respond to it in any cogent way.

For starters, I didn’t realize the implications of allowing unfettered access to a journalist whose attentions I found flattering and whom I assumed to be a friend. Janet Malcolm wrote this wry assessment of the journalistic subject in her provocative book The Journalist and the Murderer:

«Like the young Aztec men and women selected for sacrifice, who lived in delightful ease and luxury until the appointed day when their hearts were to be carved from their chests, journalistic subjects know all too well what awaits them when the days of wine and roses — the days of the interviews — are over. And still they say yes when a journalist calls, and still they are astonished when they see the flash of the knife.»

I said yes when the journalist Rick Woodward called and I was astonished at the flash of the knife. But unlike the Aztec youth, I wasn’t expecting it; that’s how naïve I was. In my arrogance and certitude that everyone surely must see the work as I did, I left myself wide-open to journalism’s greatest hazard: quotes lacking context or the sense of irony or self-deprecating humor with which they had been delivered. During the two days of interviews, not exactly “wine and roses,” that resulted in a cover story for the New York Times Magazine, I was a sitting duck preening on her nest with not the least bit of concealment. So I can hardly fault Woodward for taking his shots at me.

He wrote me afterward that he had “dined out for months” on the story, and I’m sure he did. It generated a large amount of mail to the magazine, all of which the editor was kind enough to send me, although reading it caused me the same furious pain that the article had, and that it was essentially self-inflicted made it the worse.

My intern and I read all the letters and divided them up into three crude piles: For, Against, and What the Fuck?

The Against pile (thirty-three) beat the others out, but not by much. Despite what I thought of as Woodward’s unnecessarily heavy foot on the controversy throttle, nearly half were positive (twenty-eight), and not in the creepy way you might expect (an example of semi-creepy: “As an editor and publisher of a nudist related publication, I too am subject to public humiliation…”).

Here’s how the more negative, or in most cases, critical-but-trying-to-be-helpful, letters broke down:

Seven were from people who had either been abused as children or were themselves treating abused children. These were thoughtful, concerned, sometimes fraught letters. This opening sentence from a psychotherapist in Colorado is typical of the heightened feeling: “The cover article on Sally Mann stirred me greatly.” Several recounted the writers’ own painful life stories.

«I went into therapy 14 months ago because of depression never thinking for one moment that there were incest issues in my past. After five months the horror of flash-backs and memories began. I was incested [sic] over and over and horribly tortured.»

Much was made of the distinct personalities of my parents:

«Her mother is described as having a sense of propriety; her father is described as being an aloof man and as having a sense of perversity. This contrasting parental style is regularly found in abusive families.…

«She keeps a picture of her dead father in his bathrobe on her wall. Why a picture of him dead, why in his bathrobe, and why are the two combined?»

All seven letters suggested that my father had abused me, and that I had repressed the memory and was unconsciously working out some kind of psychic pathology in my photographs. The then-popular theory that repressed childhood sexual abuse can remain susceptible to therapeutic recovery was, by 1992, beginning to wobble under scientific scrutiny (though you sure wouldn’t know it from the confident assertions in the Times mailbag). I had stupidly planted this repressed-memory idea by telling Woodward that I had very few memories of what was, basically, an unmemorable childhood, and that my father had taken “terrible art pictures” of me in the nude.

A particularly agitated letter from Staten Island, with a postscript apology for the correspondent’s “primitive method of handwriting,” queried me from page one:

«Was it really art, Ms. Mann, or was it covert incest?»

It was neither. Not incest, not art, and, it turns out, not even nudity. I have now organized and scanned all my father’s large-format negatives (as distinct from the casual snapshots he and my mother took) and am chagrined to report that they contain not a single nude photograph of me — an impressive feat of discretion on my father’s part, given how much time I spent naked as a kid. I have no idea why I said that to Woodward, and I’m resigned to present-day readers making what they will of the apparent fact that I falsely remembered being photographed nude.

But so be it. Their concerns that my “inner child” is “harboring deep reservations” and that the pictures “speak more about the photographer’s repressed memories of her own childhood than of her present relationship with her children” were misplaced. The facts are pedestrian and simple: what I had intended to convey to Woodward was that my pitifully few childhood memories were primarily based on photographs, and this was true.

And not just for me, either: I believe that photographs actually rob all of us of our memory. But having few childhood memories, and those being rooted in deckle-edged, curling snapshots, does not automatically qualify me for the repressed-memory club. If that were the case, nearly all the people my age would be spilling their guts on the couch about being “incested over and over again.” We’re not. We’re just admitting that we’re old, childhood was a long time ago, and we don’t remember all that much because our human brains find only certain things, and sometimes odd ones, worthy of encoding as long-term memories.