<<< >>>

{269}

Mammals

Primates

APES

Great Apes

Great Apes

BONOBO or PYGMY CHIMPANZEE (Pan paniscus)

IDENTIFICATION: Similar to the Common Chimpanzee, but more slender and with longer limbs, a uniformly dark face, and a slight "part" in the hair on top of the head. DISTRIBUTION: Central and western Congo (Zaire); endangered. HABITAT: Tropical lowland rain forest. STUDY AREAS: Wamba and the Lomako Forest, Congo (Zaire); Yerkes Regional Primate Research Center (Georgia); San Diego Zoo; Wild Animal Park (San Diego); Frankfurt and Stuttgart Zoos, Germany.

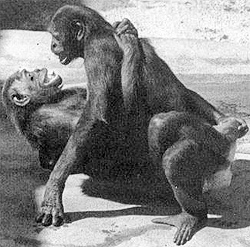

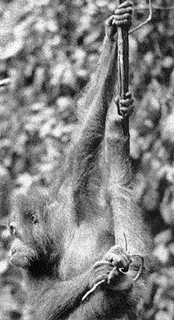

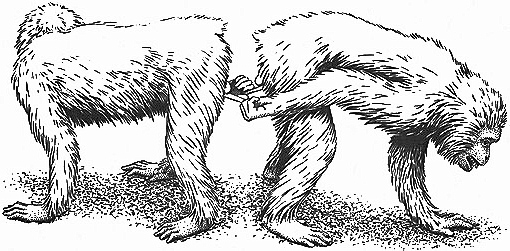

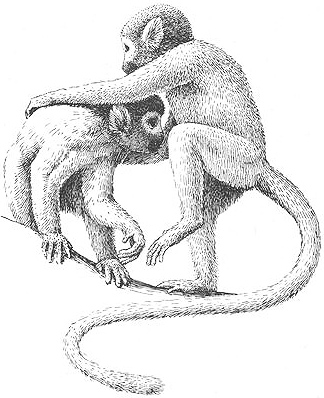

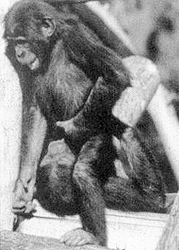

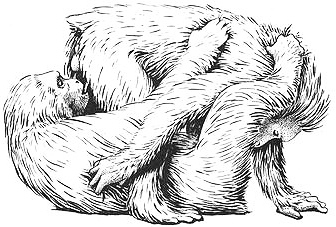

Two female Bonobos participating in "GG (genito-genital) rubbing"

Social Organization

Bonobos live in communities composed of large mixed-sex and mixed-age groups containing up to 60 or more individuals. These often divide into smaller, temporary subgroups that have a more fluid membership. On reaching adolescence (and becoming sexually mature), female Bonobos typically leave their home group and emigrate to a new one, while males usually remain in their home group for life. Females often form strongly bonded subgroups and are generally dominant to males. The mating system is promiscuous: males and females mate with multiple partners, and males do not generally participate extensively in raising their offspring.

Two female Bonobos in Congo (Zaire) "GG (genito-genital) rubbing"

Description

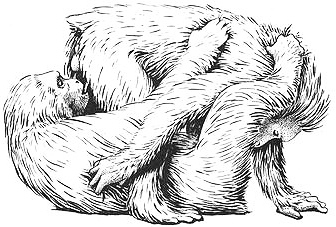

Behavioral Expression: Bonobos have one of the most varied and extensive repertoires of homosexual practices found in any animal. Females engage in an extraordinary form of mutual genital stimulation that, in many aspects, is unique to this species. Sometimes known as GG-RUBBING (for genito-genital rubbing), this behavior is usually performed in a face-to-face embracing position (heterosexual copulation is also sometimes done in this position, but not as often as in lesbian {270}

interactions). One female stands on all fours and literally "carries" or lifts her partner off the ground; the female on the bottom wraps her legs around the other's waist and clings to her as they rapidly rub their genitals against one another, directly stimulating each other's clitoris. Some scientists believe that the particular shape and location of the Bonobo's genitals have evolved specifically for lesbian rather than heterosexual interactions. During GG-rubbing, each female rhythmically swings her pelvis from side to side — precisely timed so that each partner is thrusting in opposite directions — at a rate of about two thrusts per second. This is comparable to the thrusting rate seen in males during heterosexual interactions, but males thrust vertically rather than sideways. In addition, although both homosexual and heterosexual copulations are quite brief, same-sex interactions generally last slightly longer — an average of about 15 seconds (maximum of 1 minute) compared to about 12 seconds (maximum of 45 seconds) for heterosexual matings. Sometimes females GG-rub with the same partner several times in a row.

As shown by their facial expressions, vocalizations, and genital engorgement, females experience intense pleasure — and probably orgasm — during homosexual interactions. Partners gaze intensely into each other's eyes and maintain eye contact throughout the interaction. Sometimes, females grimace or "grin" by baring their teeth wide and also utter screams or squeals that are thought to be associated with sexual climax. The Bonobo's clitoris is prominent and well-developed; during sexual arousal it undergoes a full erection of both the shaft and glans (in humans, only the glans of the clitoris becomes enlarged), swelling to nearly twice its regular size. Remarkably, clitoral penetration has occasionally been observed between females during homosexual interactions {271}

(in captivity). When penetration occurs, the females often switch to vertical thrusting (as in heterosexual mating) rather than the usual sideways hip movements.

Genital stimulation between females is sometimes performed in different positions: the two partners may both hang from a branch facing each other; one female may mount the other from behind; one female might lie on her back while the other stands facing away from her, rubbing her genitals on her recumbent partner's vulva; or both females may lie on their backs or stand rump-to-rump while GG-rubbing. In the face-to-face position, females may alternate between who is on bottom and who is on top; prior to interacting, they often "negotiate" positions by lying down with legs spread to see whether the other partner wants to be on top. GG-rubbing occurs among females of all ages, from adolescent to very old, but if an older and a younger female are interacting, often the younger female will be on top. Sexual activity may also be more common when the females are of different ranks. Homosexual interactions are often initiated with a characteristic series of "courtship" signals: approaching the partner and peering closely, standing on the hind legs and raising the arms over the head while making eye contact, and/or touching the shoulder or knee while staring. Among captive Bonobos, partners may also use a highly developed "lexicon" of manual gestures to help negotiate the position(s) to be used in sexual interactions (see pp. 66-69 for more detailed discussion).

Females may have multiple sexual partners. In one troop containing ten females, each female interacted sexually with five other females on average, and some had as many as nine different partners. Group sexual activity also occasionally takes place, with three to five females simultaneously rubbing their genitals together. Some females are considered especially {272}

"attractive" — usually because of the shape, size, and coloration of their genital swellings — and individuals may have preferred partners that they tend to interact with more often. In fact, females typically form strongly bonded, enduring relationships with one another that are fostered by sexual interactions and include such activities as mutual grooming, play, food-sharing, and alliance-formation (often for challenging males). Females generally prefer each other's company, and their same-sex bonds form the core of social organization. In addition, when new females (usually adolescents) join a troop, they often pair up with an older female with whom they have most of their sexual and affectionate interactions. These bonds need not be exclusive — either party may have sex with other females or males — but such mentorlike pairings can last for a year or more until the newcomer is fully integrated into the troop. In this species, a sort of homosexual "incest taboo" is in effect for these pair-bonds: most females are unrelated to the Bonobos in their new troop, but those who are related are not chosen as special partners. Some homosexual activity does, however, occur between mothers and their daughters.

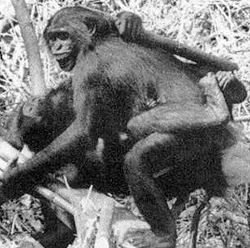

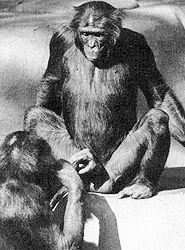

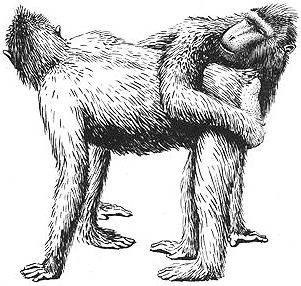

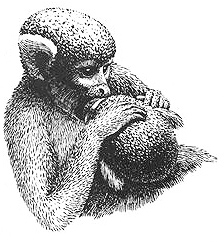

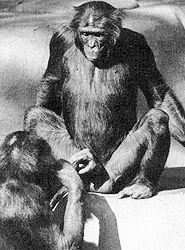

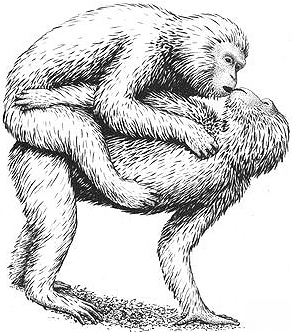

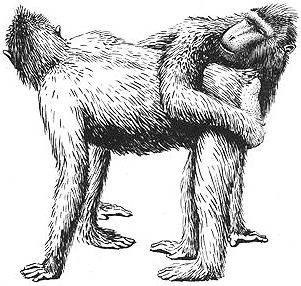

Male Bonobos also have a wide variety of homosexual interactions. Sometimes, two males mutually stimulate each other's genitals using a face-to-face position similar to GG-rubbing: one male lies on his back and spreads his legs while the other thrusts on him, rubbing their erections together (in this and all other male homosexual activity, anal penetration is not involved). If there is an age difference between partners, often the younger male will be on the bottom. Occasionally, two males hang from a branch facing each other and engage in what is known as PENIS FENCING, swinging their hips from side to side as they rub their erect penises on each other or cross them as if they were fencing with swords. Another activity is RUMP RUBBING, in which two males stand on all fours in opposite directions, pressing their buttocks against each other and mutually rubbing their anal and scrotal regions. Both males often have erections. Males also mount each other from behind and either mountee or mounter may make thrusting movements. Sometimes the males switch positions, and the mounter may scream or grin in sexual arousal as in lesbian or heterosexual interactions. Bonobo males have also been seen standing on their hind legs, one embracing the other from behind. Other sexual activities include oral sex, or fellatio, in which one male sucks another's penis at the initiation of either partner (usually seen only in younger males). Manual stimulation of the {273}

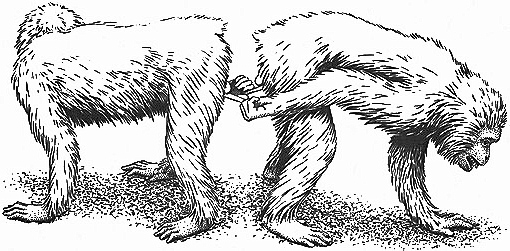

genitals by a partner also occurs: typically an adolescent male spreads his legs and presents his erect penis to an adult male, who takes the shaft in his hand and caresses it with up-and-down movements. Younger males (and occasionally females) also sometimes give each other openmouthed kisses, often with extensive mutual tongue stimulation. Although males do not appear to form pairlike bonds with sexual partners (as do some females), occasionally two or three males are intimately associated as companions, constantly accompanying each other and foraging together.

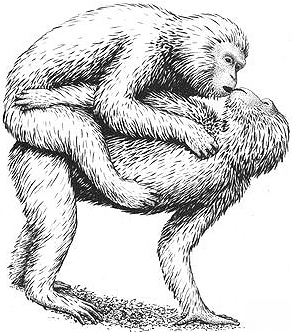

A male Bonobo mounting another male from behind

Frequency: Homosexual activity is nearly as common as heterosexual activity in Bonobos, accounting for 40-50 percent of all sexual interactions; two-thirds to three-quarters of this same-sex activity is between females (mostly GG-rubbing). Daily life among Bonobos is characterized by numerous relatively brief episodes of sexual activity scattered throughout the day, and homosexual interactions are frequent. Each female participates in GG-rubbing on average once every two hours or so, and some newcomers to a troop do so even more often, on an hourly basis.

Two younger male Bonobos engaging in fellatio

Orientation: Virtually all Bonobos are bisexual, interacting sexually with both males and females. In fact, motherhood and homosexual activity are fully integrated among Bonobos, as a female often GG-rubs with another female while her infant is clinging to her belly. Usually same-sex and opposite-sex activities are interspersed or alternated, although both may occur simultaneously during group sexual interactions. Nevertheless, it appears that — among some females at least — homosexual activity is preferred. Although females vary along a continuum, with one-third to nearly 90 percent of their interactions being with partners of the same sex, overall there is often a predominance of homosexual activity. An average of two-thirds of all sexual interactions among females are with other females, and individuals generally have more female than male sexual partners. In addition, females have sometimes been observed consistently ignoring males who are soliciting them for sex, preferring instead to GG-rub with each other.

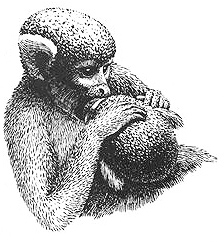

An adult male Bonobo (left) manually stimulating the penis of a younger male

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Variety, flexibility, and frequency of sexual interactions are not limited to contact between Bonobos of the same sex — heterosexual activity is replete with nonreproductive behaviors. Rump rubbing, fellatio, and manual stimulation of the genitals by either sex (including fondling of the scrotum) are all aspects of male-female sexual interactions. In addition, females occasionally mount males from behind (REVERSE mounts), and heterosexual copulation often does not involve penetration and/or ejaculation, but simply mutual rubbing of genitals. Both male and female Bonobos also masturbate (males sometimes using inanimate objects to stimulate themselves). Group sexual activity occurs as well, often with one individual thrusting against a pair who are copulating, and individuals may participate in several bouts of heterosexual activity in rapid succession. Sometimes, because of the frequency and persistence of sexual invitations — often associated with begging for food — individuals (especially males) may even become annoyed and try to avoid {274}

further heterosexual interaction. In addition, females occasionally cooperate with one another in harassing and attacking males, in some cases causing severe injuries by holding a male down and biting his ears, fingers, toes, or genitals.

Bonobos mate during all phases of a female's sexual cycle, and about a third of copulations occur during periods when fertilization is unlikely or impossible. Mating also takes place during pregnancy, sometimes as late as one month before delivery. Both adult males and females interact sexually with adolescents and juveniles (three-to-nine-year-olds). In fact, young females go through a five-to-six-year period sometimes referred to as ADOLESCENT STERILITY (although no pathology is involved) during which they actively participate in heterosexual mating (often with adults) but never get pregnant. Sexual behavior between adults and infants of both sexes is also common — about a third of the time it is initiated by the infant and may involve genital rubbing and full copulatory postures (including penetration of an adult female by a male infant). Another form of nonreproductive sexuality involves contact with other species: younger male Bonobos have occasionally been observed engaging in playful sexual interactions with redtail monkeys (Cercopithecus ascanius) in the wild.

Two male Bonobos "rump rubbing"

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

* Blount, B. G. (1990) "Issues in Bonobo (Pan paniscus) Sexual Behavior." American Anthropologist 92: 702-14.

* Enomoto, T. (1990) "Social Play and Sexual Behavior of the Bonobo (Pan paniscus) With Special Reference to Flexibility." Primates 31:469-80.

* Furuichi, T. (1989) "Social Interactions and the Life History of Female Pan paniscus in Wamba, Zaire." International Journal of Primatology 10:173-97.

* Hashimoto, C. (1997) "Context and Development of Sexual Behavior of Wild Bonobos (Pan paniscus) at Wamba, Zaire." International Journal of Primatology 18:1-21.

* Hashimoto, C., T. Furuichi, and O. Takenaka (1996) "Matrilineal Kin Relationships and Social Behavior of Wild Bonobos (Pan paniscus): Sequencing the D-loop Region of Mitochondrial DNA." Primates 37:305-18.

* Hohmann, G. and B. Fruth (1997) "The Function of Genito-Genital Contacts among Female Bonobos (Pan paniscus)." In M. Taborsky and B. Taborsky, eds., Contributions to the XXV International Ethological Conference, p. 112. Advances in Ethology no. 32. Berlin: Blackwell Wissenschafts-Verlag.

* Idani, G. (1991) "Social Relationships Between Immigrant and Resident Bonobo (Pan paniscus) Females at Wamba." Folia Primatologica 57:83-95.

* Kano, T. (1992) The Last Ape: Pygmy Chimpanzee Behavior and Ecology. Stanford: Stanford University Press. Translated from the Japanese by Evelyn Ono Vineberg.

* --- (1990) "The Bonobos' Peaceable Kingdom." Natural History 99(11):62-71.

* --- (1989) "The Sexual Behavior of Pygmy Chimpanzees." In P. G. Heltne and L. A. Marquardt, eds., Understanding Chimpanzees, pp.176-83. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

* --- (1980) "Social Behavior of Wild Pygmy Chimpanzees (Pan paniscus) of Wamba: A Preliminary Report." Journal of Human Evolution 9:243-60.

* Kitamura, K. (1989) "Genito-Genital Contacts in the Pygmy Chimpanzee (Pan paniscus)." African Study Monographs 10:49-67.

* Kuroda, S. (1984) "Interactions Over Food Among Pygmy Chimpanzees." In R. L. Susman, ed., The Pygmy Chimpanzee: Evolutionary Biology and Behavior, pp. 301-24. New York: Plenum Press.

* --- (1980) "Social Behavior of Pygmy Chimpanzees." Primates 21:181-97.

* Parish, A. R. (1996) "Female Relationships in Bonobos (Pan paniscus): Evidence for Bonding, Cooperation, and Female Dominance in a Male-Philopatric Species." Human Nature 7:61-96.

* --- (1994) "Sex and Food Control in the 'Uncommon Chimpanzee': How Bonobo Females Overcome a Phylogenetic Legacy of Male Dominance." Ethology and Sociobiology 15:157-79.

* Roth, R. R. (1995) "A Study of Gestural Communication During Sexual Behavior in Bonobos (Pan paniscus Schwartz)". Master's thesis, University of Calgary. {275}

Sabater Pi, J., M. Bermejo, G. Illera, and J. J. Vea (1993) "Behavior of Bonobos (Pan paniscus) Following Their Capture of Monkeys in Zaire." International Journal of Primatology 14:797-804.

* Savage, S. and R. Bakeman (1978) "Sexual Morphology and Behavior in Pan paniscus." In D. J. Chivers and J. Herbert, eds., Recent Advances in Primatology, vol. 1, pp. 613-16. New York: Academic Press.

* Savage-Rumbaugh, E. S., and R. Lewin (1994) Kanzi: The Ape at the Brink of the Human Mind. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

* Savage-Rumbaugh, E. S., and B. J. Wilkerson (1978) "Socio-sexual Behavior in Pan paniscus and Pan troglodytes. A Comparative Study." Journal of Human Evolution 7:327-44.

* Savage-Rumbaugh, E. S., B. J. Wilkerson and R. Bakeman (1977) "Spontaneous Gestural Communication among Conspecifics in the Pygmy Chimpanzee (Pan paniscus)." In G. Bourne, ed., Progress in Ape Research, pp. 97-116. New York: Academic Press.

* Takahata, Y., H. Ihobe, and G. Idani (1996) "Comparing Copulations of Chimpanzees and Bonobos: Do Females Exhibit Proceptivity or Receptivity?." In W. C. McGrew, L. F. Marchant, and T. Nishida, eds., Great Ape Societies, pp. 146-55. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Takeshita, H., and V. Walraven (1996) "A Comparative Study of the Variety and Complexity of Object Manipulation in Captive Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and Bonobos (Pan paniscus)." Primates 37: 423-41.

* Thompson-Handler, N., R. K. Malenky, and N. Badrian (1984) "Sexual Behavior of Pan paniscus Under Natural Conditions in the Lomako Forest, Equateur, Zaire." In R.L. Susman, ed., The Pygmy Chimpanzee: Evolutionary Biology and Behavior, pp. 347-68. New York: Plenum Press.

* de Waal, F. B. M. (1997) Bonobo: The Forgotten Ape. Berkeley: University of California Press.

* --- (1995) "Sex as an Alternative to Aggression in the Bonobo." In P. A. Abramson and S. D. Pinkerton, eds., Sexual Nature, Sexual Culture, pp. 37-56. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

* --- (1989a) Peacemaking Among Primates. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

* --- (1989b) "Behavioral Contrasts Between Bonobo and Chimpanzee." In P. G. Heltne and L. A. Marquardt, eds., Understanding Chimpanzees, pp. 154-73. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

* --- (1988) "The Communicative Repertoire of Captive Bonobos (Pan paniscus), Compared to That of Chimpanzees." Behavior 106:184-251.

* --- (1987) "Tension Regulation and Nonreproductive Functions of Sex in Captive Bonobos (Pan paniscus)." National Geographic Research 3:318-35.

Walraven, V., L. Van Elsacker, and R. F. Verheyen (1993) "Spontaneous Object Manipulation in Captive Bonobos." In L. Van Elsacker, ed., Bonobo Tidings: Jubilee Volume on the Occasion of the 150th Anniversary of the Royal Zoological Society of Antwerp, pp. 25-34. Leuven: Ceuterick Leuven.

* White, F., and N. Thompson-Handler (1989) "Social and Ecological Correlates of Homosexual Behavior in Wild Pygmy Chimpanzees, Pan paniscus." American Journal of Primatology 18:170.

{276}

Great Apes

Great Apes

COMMON CHIMPANZEE (Pan troglodytes)

IDENTIFICATION: The familiar small ape, with black, gray, or brownish fur, prominent ears, and variable facial coloring, from black to brown and pink (especially in younger animals). DISTRIBUTION: Western and central Africa, from southeastern Senegal to western Tanzania; endangered. HABITAT: Woodland savanna, grassland, tropical rain forest. STUDY AREAS: Mahale Mountains National Park and the Gombe Stream National Park, Tanzania; Budongo Forest, Uganda; eastern Congo (Zaire); Arnhem Zoo, the Netherlands; Anthropoid Station, Tenerife; Yale University Primate Laboratory and chimpanzee colony (New Haven, Conn., Franklin, N.H., and Orange Park, Fla.); ARL Chimpanzee Colony, N.Mex.; Delta Regional Primate Research Center, La.; subspecies

P.t. schweinfurthii.

Social Organization

Common Chimpanzees live in groups or communities of 40-60 individuals, usually with twice as many adult females as males. Within each group, smaller subgroups often form, and some individuals form longer-lasting bonds with each other as part of a complex network of social and communicative interactions. The mating system is promiscuous or polygamous: males and females each mate with multiple partners, and males do not generally participate in raising their own offspring.

The kiss: two male Chimpanzees

Description

Behavioral Expression: Female Common Chimpanzees participate in a variety of same-sex activities. One form of mutual genital stimulation is sometimes known as BUMPRUMP: two females, standing on all fours and facing in opposite directions, rub their rumps together (usually in an up-and-down motion), stimulating their genital and anal regions. Sometimes one female lies on top of the other in a face-to-face position — or the two sit facing one another — rubbing their genitals together. Mounting also occurs in the front-to-back position typical of heterosexual mating. Unlike male-female mountings, though, the angle and position of the mounting female's body and arms may be slightly different from that of a male, her pelvic thrusts may be slower or more perfunctory, and she may rub against the other female's genitals with her belly rather than her own genital region. Occasionally female Chimps also engage in cunnilingus: one individual presents her {277}

buttocks by crouching in front of the other, who stimulates her external genitalia with her lips and tongue.

Among males, several different kinds of same-sex interactions occur. Manual contact or stimulation of a partner's genitals, for example, can involve fondling, rubbing, or gripping of the penis and/or touching of the scrotum, sometimes while the partner makes pelvic thrusts that "bounce" his genitals on his partner's hand. Chimps occasionally also engage in fellatio, mutual penis-rubbing while sitting face-to-face, mounting in a front-to-back position (sometimes with pelvic thrusts or body shaking), and even insertion of a finger into the partner's anus and oralanal "grooming" in a 69 position. A number of these activities — notably genital touching, mounting, and anal contact — occur as ritualized sexual gestures in the context of greeting, enlisting of support, reconciliation, and/or reassurance. They are often combined with affectionate gestures between males such as embracing, kissing (including openmouthed contact), grooming, and genital kissing or nuzzling. Males who participate in such activities may be bonded together in a mutually supportive "friendship" or

COALITION. Occasionally male Chimpanzees also interact sexually with male Savanna Baboons in the wild. One adolescent Chimp, for example, was observed holding and fondling the penis of an adult male Baboon.

Transgendered or intersexual Common Chimpanzees occasionally occur as well. One individual who was physically and anatomically a male was chromosomally a mosaic, combining both the male (XY) and the female (XX) chromosome types.

Frequency: The prevalence of same-sex activities between male Common Chimpanzees is highly variable. Mounting between males constitutes anywhere from 1-2 percent to one-third or one-half of the behaviors involved in reassurance, enlistment of support, and other activities during or following conflicts. Kissing and embracing between males constitute from 12-30 percent of such interactions (depending on the population). Overall, 29-33 percent of all mounting activity occurs between males. Less detailed information is available for females, but a similar range of frequencies is probably involved. Other homosexual activities such as bumprump and oral or manual stimulation of genitals have so far been observed largely in captivity, where they may be fairly common.

Orientation: Most adult male Chimpanzees that participate in same-sex mounting, genital handling, or other activities also mate with females. Younger (adolescent or juvenile) males, who occasionally engage in such activities as fellatio or mutual genital rubbing, may be less heterosexually involved. In some populations, virtually all adult males participate in same-sex mounting, although such behavior may constitute anywhere from one-fifth to three-quarters of an individual's mounting activity. Females that participate in same-sex activities are also usually functionally bisexual, copulating with males as well. However, a few individuals appear to be more exclusively homosexual: one female, for example, refused to mate with males and was only involved sexually with other females for many years. She even developed a close relationship with another female and her {278}

offspring. Socially, she occupied an intermediate position between the male and female subgroups: she often associated with males and "ganged up" with them against other individuals, but she also maintained primary bonds with females and sometimes even defended them against the sexual advances of males. Later, however, she also mated with males.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Common Chimpanzees engage in a variety of nonprocreative heterosexual practices that parallel their same-sex behaviors. Heterosexual oral sex involves both cunnilingus (males licking the vagina or mouthing the labia) and fellatio (females sucking or nuzzling the penis). Manual stimulation of the genitals also occurs: males sometimes insert a finger into the vagina (the female may then move his hand in order to stimulate herself), while females occasionally fondle their partner's penis. In addition, bumprump takes place between males and females (sometimes including thrusting and scrotum handling), and both sexes masturbate — stimulating their own genitals manually or with various implements. Some males even perform AUTO-FELLATIO, i.e., they suck their own penis. Male Chimpanzees occasionally mount females without achieving penetration or ejaculate after withdrawing; they may also mate with females who are not in heat. Another form of nonprocreative sex is copulation during pregnancy: some females participate in heterosexual activity for 75-80 percent of the time that they are pregnant. In addition, male Chimps have been observed copulating with female Savanna Baboons in the wild.

When females are in heat, they typically mate numerous times and with multiple partners — as often as six or more times a day (sometimes with two to seven males in quick succession), for a total of several hundred times for each baby conceived. In some cases, though, heterosexual relations are less than amicable: males occasionally try to force females to consort and mate with them by threatening and even violently attacking them, and females often display "blunt refusal" or "abhorrence" reactions toward the advances of older males. Copulations are often interrupted or harassed by other Chimps trying to disrupt the sexual activities. In addition, infanticide and even cannibalism occasionally occur. For example, infants conceived outside the community may be killed by the resident males, and most females mate with males belonging to their own social group. However, in some populations a considerable number of females seek partners outside their group, engaging in "furtive" matings with them. In one community, for example, more than half of all offspring were sired by males living in other groups.

Although incestuous matings between adults are not common, mothers engage in sexual activity with their infant sons fairly often. Young females typically experience a one-to-three-year period of ADOLESCENT STERILITY after their first menstruation, during which time they mate heterosexually without conceiving. Some adult females practice a unique form of birth control: they simulate the contraceptive effect of nursing by stimulating their own nipples, in some cases preventing pregnancy for up to ten years. Females may also experience a postreproductive or "menopausal" period later in their lives, lasting up to two years (about 4-5 percent {279}

of the maximum life span). During this time they often continue to mate, accounting for up to 20 percent of all female sexual activity in a group.

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

* Adang, O. M. J., J. A. B. Wensing, and J. A. R. A. M. van Hooff (1987) "The Arnhem Zoo Colony of Chimpanzees Pan troglodytes: Development and Management Techniques." International Zoo Yearbook 26:236-48.

* Bingham, H. C. (1928) "Sex Development in Apes." Comparative Psychology Monographs 5:1-165.

Bygott, J. D. (1979) "Agonistic Behavior, Dominance, and Social Structure in Wild Chimpanzees of the Gombe National Park." In D. A. Hamburg and E. R. McCown, eds., The Great Apes, pp. 405-28. Menlo Park, Calif.: Benjamin Cummings.

* --- (1974) "Agonistic Behavior and Dominance in Wild Chimpanzees." Ph.D. thesis, Cambridge University.

Dahl, J. F., K. J. Lauterbach, and C. A. Duffey (1996) "Birth Control in Female Chimpanzees: Self-Directed Behaviors and Infant-Mother Interactions." American Journal of Physical Anthropology supp. 22:93.

* Egozcue, J. (1972) "Chromosomal Abnormalities in Primates." In E. 1. Goldsmith and J. Moor-Jankowski, eds., Medical Primatology 1972, part I, pp. 336-41. Basel: S. Karger.

Gagneux, P., D. S. Woodruff, and C. Boesch (1997) "Furtive Mating in Female Chimpanzees." Nature 387:358-59.

* Goodall, J. (1986) The Chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of Behavior. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press.

(1977) "Infant Killing and Cannibalism in Free Living Chimpanzees." Folia Primatologica 28:259-82.

* --- (1965) "Chimpanzees of the Gombe Stream Reserve." In 1. deVore, ed., Primate Behavior: Field Studies of Monkeys and Apes, pp. 425-73. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

* Kohler, W. (1925) The Mentality of Apes. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

* Kollar, E. J., W. C. Beckwith, and R. B. Edgerton (1968) "Sexual Behavior of the ARL Colony Chimpanzees." Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 147:444-59.

* Kollar, E. J., R. B. Edgerton, and W. C. Beckwith (1968) "An Evaluation of the Behavior of the ARL Colony Chimpanzees." Archives of General Psychiatry 19:580-94.

* Kortlandt, A. (1962) "Chimpanzees in the Wild." Scientific American 206(5):128-38.

* Lawick-Goodall, J. van (1968) "The Behavior of Free-Living Chimpanzees in the Gombe Stream Reserve." Animal Behavior Monographs 1:161-311.

* Nishida, T. (1997) "Sexual Behavior of Adult Male Chimpanzees of the Mahale Mountains National Park, Tanzania." Primates 38:379-98.

--- (1990) The Chimpanzees of the Mahale Mountains: Sexual and Life History Strategies. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press.

--- (1979) "The Social Structure of Chimpanzees of the Mahale Mountains." In D. A. Hamburg and E. R. McCown, eds., The Great Apes, pp. 73-121. Menlo Park, Calif.: Benjamin Cummings.

* --- (1970) "Social Behavior and Relationship Among Wild Chimpanzees of the Mahali Mountains." Primates 11:47-87.

* Nishida, T., and K. Hosaka (1996) "Coalition Strategies Among Adult Male Chimpanzees of the Mahale Mountains, Tanzania." In W. C. McGrew, L. F. Marchant, and T. Nishida, eds., Great Ape Societies, pp. 114-34. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

* Reynolds, V., and F. Reynolds (1965) "Chimpanzees of the Budongo Forest." In 1. deVore, ed., Primate Behavior: Field Studies of Monkeys and Apes, pp. 368-424. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Takahata, Y., N. Koyama, and S. Suzuki (1995) "Do the Old Aged Females Experience a Long Postreproductive Life Span?: The Cases of Japanese Macaques and Chimpanzees." Primates 36:169-80.

Tutin, C. E. G., and P. R. McGinnis (1981) "Chimpanzee Reproduction in the Wild." In C.E. Graham, ed., Reproductive Biology of the Great Apes, pp. 239-64. New York: Academic Press.

* Tutin, C. E. G., and W. C. McGrew (1973a) "Chimpanzee Copulatory Behavior." Folia Primatologica 19:237-56.

--- (1973b) "Sexual Behavior of Group-Living Adolescent Chimpanzees." American Journal of Physical Anthropology 38:195-200.

* de Waal, F. B. M. (1982) Chimpanzee Politics: Power and Sex Among Apes. New York: Harper & Row.

* de Waal, F. B. M., and J. A. R. A. M. van Hooff (1981) "Side-directed Communication and Agonistic Interactions in Chimpanzees." Behavior 77:164-98.

Wrangham, R. W. (1997) "Subtle, Secret Female Chimpanzees." Science 277:774-75.

* Yerkes, R. M. (1939) "Social Dominance and Sexual Status in the Chimpanzee." Quarterly Review of Biology 14:115-36.

{280}

Great Apes

Great Apes

GORILLA (Gorilla gorilla)

IDENTIFICATION: A massive ape (adult males generally weigh over 300 pounds) with black fur; old males are called silverbacks because of the silvery-gray fur on their backs. DISTRIBUTION: Central Africa including Congo (Zaire), Uganda, Rwanda; southeastern Nigeria to southern Congo; endangered. HABITAT: Bamboo forests, rain forests. STUDY AREAS: Virunga Mountains, Rwanda and Congo (Zaire), subspecies G.g. beringei, the Mountain Gorilla; Basel, Metro Toronto, and St. Louis Zoos, subspecies G.g. gorilla, the Lowland Gorilla.

Social Organization

Gorillas live in small groups of eight to fifteen individuals, usually consisting of three to six adult females, one mature male, one to two juvenile males, and five to seven immature offspring. All-male groups also regularly occur. The mating system is polygynous, i.e., the mature male mates with all of the females in the group. The females are usually not related to each other, since they generally leave their family group once reaching adulthood — in many other group-living primates, males leave a core group of (usually related) females.

Description

Behavioral Expression: Within her group, a female Gorilla sometimes forms an intense pairlike friendship with another female, spending as much time with her as with the breeding male of the group. Her interactions with this "favorite" female consist of constant touching while they spend time together, sitting with each other or lying one against the other, and frequent mutual grooming. Female Gorillas also frequently have sex with other females in their group. In a typical lesbian interaction, one female approaches another directly, often making copulatory vocalizations, after which they may sit quietly together for a while. Often they will begin to fondle each other's genitals or bring their face into intimate contact with the other's vulva, smelling or touching with their mouths. This is usually followed by embracing in a face-to-face position (usually lying down) with rubbing of the genitals against each other, sometimes accompanied by growling, grunting, screaming, or pulsing whimpers. The animals may also pause during periods of pelvic thrusting to caress each other, shift their positions, or masturbate themselves. {281}

Lesbian sexual activity is notable for its differences from heterosexual copulation, probably related to an emphasis on achieving mutual pleasure. First of all, the more intimate face-to-face position is rarely used between males and females, who instead mate with the male mounting from behind (and often with the male thrusting and vocalizing significantly less than his partner). Sexual interactions between females are also generally more affectionate, involving much more embracing and grooming, and they usually last longer. One study revealed that sexual interactions between females last on average five times longer than heterosexual ones, and that lesbian activity involves considerably more thrusting and genital stimulation.

Female Gorillas also exhibit clear preferences for particular female sexual partners within their group. Although lesbian activity generally occurs among all members of a group, each female usually has a favorite partner with whom she interacts more often. Homosexuality is also integrated into the general reproductive cycle of the group: breeding females (including mothers) have sex with other females as much as do nonbreeding females, and lesbian sex is common even during pregnancy, sometimes as late as a week or two before birth.

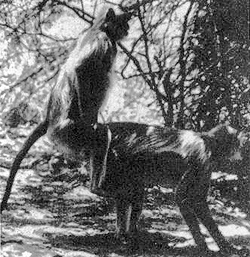

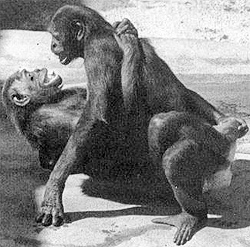

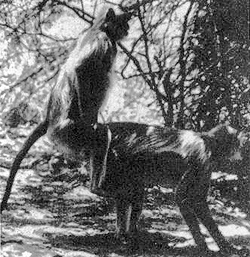

Although male Gorillas (especially younger animals) sometimes mount each other in cosexual groups, homosexuality occurs most commonly in all-male groups, where probably more than 90 percent of all same-sex activity between males takes place. Such groups result when females leave their home group to join another, or when males occasionally leave their own group upon reaching maturity and band together. All-male groups persist for many years and have a complex network of homosexual pairings. Each male has preferred partners whom he courts and has sex with; some interact with only one other male in the group, while others have multiple partners (up to five have been recorded for one individual). Durations of individual pairings can be anywhere from a few months to a year or more. Participants are sometimes related to each other: in one all-male group, about 40 percent of all homosexual activity occurred between half brothers. There is often intense competition among the males for "preferred" partners — often the younger males — and older, higher-ranking males frequently "guard" their favorite males and fight to protect them from the advances of other males. Nevertheless, rates of aggression are significantly lower in all-male groups than in cosexual groups, and some male groups exhibit a high degree of cohesiveness attributable to the sexual bonding and mediating activities of their members.

When one male Gorilla is courting another, he approaches while making intense panting sounds; sometimes contact is initiated with one (or both) males reaching out to touch the other, or one may make a more subtle soliciting approach. Sexual activity involves one male mounting another and thrusting, in either the face-to-face or front-to-back position; both males often emit grumbling, growling, or panting sounds. Orgasm is signaled when the animal emits a deep sigh on dismounting, and often there is direct evidence of ejaculation (e.g., semen spilled on his partner). Most males both mount and are mounted, except for the oldest silverback males, who only mount. Like lesbian interactions, male homosexual encounters tend to last, on average, longer than heterosexual ones and to use the {282}

face-to-face position more often than in male-female interactions (though less often than between females). Male Gorillas also touch and fondle each other's genitals in addition to mounting one another.

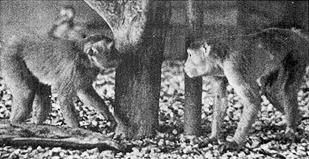

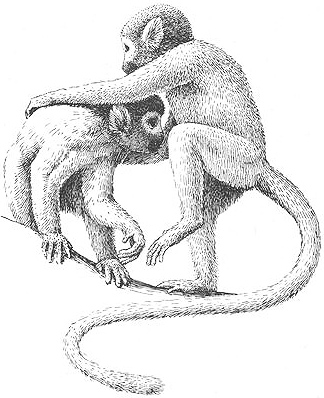

Male Gorillas having sex with each other in the mountain rain forests of Rwanda, showing two mounting positions: front-to-back (left) and face-to-face

Frequency: In cosexual groups, 9 percent of all sexual activity is lesbian and 58 percent of all social/affectionate interactions of females are with other females (mostly with their "favorite" partner); about 2 percent of mounting episodes occur between adult males in such groups. Among younger animals (e.g., adolescents and juveniles) in cosexual groups, 7-36 percent of mounts are between males and 9-14 percent between females. Male homosexual courtship and copulation occur daily in some all-male groups and are thought to exceed the amount of heterosexual activity that takes place in cosexual groups. Some males may engage in homosexual copulation more than 75 times a year in such groups, and homosexual courtship, at its peak, can take place as often as 7 times an hour. Up to 10 percent of groups in some populations are all-male, and Gorillas spend an average of six years in such groups, with some males staying ten or more years (and even occasionally remaining until their death).

Orientation: Many female Gorillas are bisexual, having sexual and affectionate relationships with both males and females, but there are clear differences in the extent to which various individuals participate in homosexual versus heterosexual activity. In general, it appears that a continuum exists from those females who prefer lesbian activity (they account for a large proportion of the same-sex interactions), to those who have a fairly equal amount of interaction with both males and females, to those who interact primarily with males. Many male Gorillas are probably sequentially {283}

bisexual, spending portions of their lives having only homosexual encounters (in all-male groups), followed by periods of only heterosexual interactions, and so on. Other males, especially younger ones, may be simultaneously bisexual. Depending on the circumstances (such as the particular group composition), some males may also have primarily or exclusively homosexual interactions throughout their lives, while others may have only heterosexual ones, but it appears that all males at least have the capacity for bisexuality.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

As noted above, sex (both heterosexual and homosexual) during pregnancy is common among Gorillas. Both males and females also engage in masturbation, and younger animals frequently participate in nonpenetrative sexual activity. Mountings of the latter type are usually incestuous, involving siblings, half siblings, or (more rarely) parents and their offspring (or their siblings' offspring). In captivity, oral sex and manual stimulation of genitals have also been observed in heterosexual interactions. Male Gorillas generally appear to have less interest in sex than females and are sometimes rather reluctant or perfunctory participants in mating. Heterosexual interactions are nearly always initiated by females (whose advances are often initially ignored by the males), males often thrust and vocalize much less than females during copulation (often for no more than 20 seconds), and females generally determine when a particular sexual interaction is finished. However, females may be sexually inactive for up to three or four years while nursing their young. Infanticide is quite common among wild Gorillas: more than 40 percent of all infant deaths in one population were due to infanticide, usually by an adult male trying to gain breeding access to a female (although females have been known to kill infants as well). Probably all adult males commit infanticide at least once during their lifetime, while most females are likely to lose at least one infant during their lifetime to killing by another of their own species.

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

* Coffin, R. (1978) "Sexual Behavior in a Group of Captive Young Gorillas." Boletin de Estudios Medicos y Bi-ologicos 30:65-69.

* Fischer, R. B. and R.D. Nadler (1978) "Affiliative, Playful, and Homosexual Interactions of Adult Female Lowland Gorillas." Primates 19:657-64.

* Fossey, D. (1990) "New Observations of Gorillas in the Wild." In Grzimek's Encyclopedia of Mammals, vol. 2, pp. 449-62. New York: McGraw-Hill.

(1984) "Infanticide in Mountain Gorillas (Gorilla gorilla beringei) with Comparative Notes on Chimpanzees." In G. Hausfater and S. B. Hrdy, eds., Infanticide: Comparative and Evolutionary Perspectives, pp. 217-35. New York: Aldine.

* --- (1983) Gorillas in the Mist. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

* Harcourt, A. H. (1988) "Bachelor Groups of Gorillas in Captivity: The Situation in the Wild." Dodo 25:54-61.

* --- (1979a) "Social Relations Among Adult Female Mountain Gorillas." Animal Behavior 27:251-64.

--- — (1979b) "Social Relationships Between Adult Male and Female Mountain Gorillas in the Wild." Animal Behavior 27:325-42.

* Harcourt, A. H., D. Fossey, K. J. Stewart, and D. P. Watts (1980) "Reproduction in Wild Gorillas and Some Comparisons with Chimpanzees." Journal of Reproduction and Fertility suppl. 28:59-70.

Harcourt, A. H., and K. J. Stewart (1978) "Sexual Behavior of Wild Mountain Gorillas." In D. J. Chivers and J. Herbert, eds., Recent Advances in Primatology, vol. 1, pp. 611-12. New York: Academic Press. {284}

* Harcourt, A. H., K. J. Stewart, and D. Fossey (1981) "Gorilla Reproduction in the Wild." In C. E. Graham, ed., Reproductive Biology of the Great Apes, pp. 265-79. New York: Academic Press.

* Hess, J. P. (1973) "Some Observations on the Sexual Behavior of Captive Lowland Gorillas, Gorilla g. gorilla (Savage and Wyman)." In R. P. Michael and J. H. Crook, eds., Comparative Ecology and Behavior of Primates, pp. 507-81. London: Academic Press.

* Nadler, R. D. (1986) "Sex-Related Behavior of Immature Wild Mountain Gorillas." Developmental Psychobiology 19:125-37.

* Porton, I., and M. White (1996) "Managing an All-Male Group of Gorillas: Eight Years of Experience at the St. Louis Zoological Park." In AAZPA Regional Conference Proceedings, pp. 720-28. Wheeling, W.V.: American Association of Zoological Parks and Aquariums.

* Robbins, M. M. (1996) "Male-Male Interactions in Heterosexual and All-Male Wild Mountain Gorilla Groups." Ethology 102:942-65.

* --- (1995) "A Demographic Analysis of Male Life History and Social Structure of Mountain Gorillas." Behavior 132:21-47.

* Schaller, G. (1963) The Mountain Gorilla. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

* Stewart, K. J. (1977) "Birth of a Wild Mountain Gorilla (Gorilla gorilla beringei)." Primates 18:965-76.

Watts, D. P. (1990) "Mountain Gorilla Life Histories, Reproductive Competition, and Sociosexual Behavior and Some Implications for Captive Husbandry." Zoo Biology 9:185-200.

--- (1989) "Infanticide in Mountain Gorillas: New Cases and a Reconsideration of the Evidence." Ethology 81:1-18.

* Yamagiwa, J. (1987a) "Intra- and Inter-Group Interactions of an All-Male Group of Virunga Mountain Gorillas (Gorilla gorilla beringei)." Primates 28:1-30.

* --- (1987b) "Male Life History and the Social Structure of Wild Mountain Gorillas (Gorilla gorilla beringei)." In S. Kawano, J. H. Connell, and T. Hidaka, eds., Evolution and Coadaptation in Biotic Communities, pp. 31-51. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press.

Great Apes

Great Apes

ORANG-UTAN (Pongo pygmaeus)

IDENTIFICATION: A medium-sized ape (adult males generally weigh around 170 pounds) with a long, reddish brown coat; some older males develop prominent cheek pads or "flanges." DISTRIBUTION: Sumatra, Borneo (Indonesia); vulnerable. HABITAT: Swamps, lowland and mountain rain forests. STUDY AREAS: Ketambe region of North Sumatra, Indonesia, subspecies P.p. abelii, the Sumatran Orang-utan; Regent's Park Zoo and Singapore Zoological Garden, including subspecies P.p. pygmaeus, the Bornean Orang-utan.

{285}

Social Organization

Adult Orang-utans are largely solitary — males and females live separate from each other and interact only when the female is ready to mate. Younger Orangs, however, are more sociable and may actively seek each other's company and interact in groups. The mating system is polygynous: males copulate with multiple females and no long-lasting heterosexual pairing occurs, although males and females may "consort" together for shorter periods during mating. Males do not participate in parenting.

Description

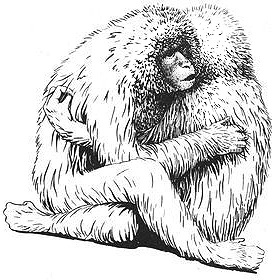

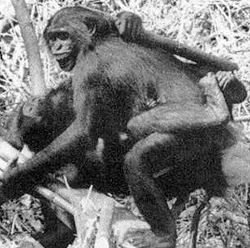

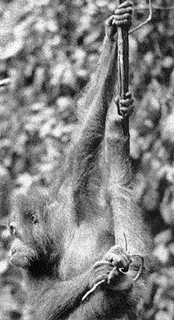

Behavioral Expression: Orang-utans engage in a variety of homosexual activities, including a range of different sexual techniques and various affectionate and pairing behaviors. Mounting among male Orangs, especially younger adults (10-15 years old) and adolescents (7-10 years old) often develops into full anal intercourse, with erection of the penis, pelvic thrusting, penetration, and ejaculation. In a more unusual type of homosexual penetration, a male sometimes tries to insert his penis into the small hollow formed when his partner's penis retracts. Another prominent homosexual activity is fellatio (oral-genital contact): one male will lick and suck another's erect penis. In some cases, males take turns fellating each other. Males occasionally also fondle and touch the erect penis of another male, often examining the organ closely by parting the hairs in the genital region. Lesbian activity in Orangs usually involves one female fondling the genitals of another female, often inserting her fingers (thumb or other digits) into the vagina of the other. Sometimes she also masturbates herself with her foot while she is penetrating the other female. Mounting rarely, if ever, occurs among female Orangs, unlike in many other animals in which females engage in homosexual behavior. Female homosexual encounters may last for up to 12 minutes, comparable to the 10-15 minute duration of most heterosexual copulations. Although Orang-utans are usually willing participants in homosexual encounters, sometimes one animal is more reluctant and the partner will then attempt to restrain him or her, for example by using the feet to hold him or her down. However, this contrasts sharply with heterosexual encounters, in which females often scream and struggle violently while males attempt to forcibly mate with them (see the discussion on heterosexualities below).

Sexual behavior often occurs within a "bonding" or special friendship-like pairing between younger animals of the same sex. Two males or two females may become quite attached, following one another over several days, playing together (including play-wrestling), sharing food, and generally spending a great deal of time together and coordinating their activities. One partner may even throw a "temper tantrum" when the other ventures too far away or fails to wait for its companion. Female Orangs have also been known to compete with males for sexual access to a favorite female partner with whom they later develop a bonded relationship. Same-sex companions demonstrate a number of affectionate behaviors toward each other — females, for example, may embrace, cling to one other, walk in tandem, or groom each other, and males may "kiss" each other. While in {286}

some cases this mouth-to-mouth contact may be for the exchange of food or drink, in other cases it appears to be more of an affectionate or greeting gesture. Such companionships also develop between animals of the opposite sex, and indeed they resemble in many ways the "consortships" that sometimes characterize heterosexual mating relations. Companionships, however, need not involve any sexual contact, whether between animals of the same or opposite sex.

Homosexual interactions sometimes also occur between male Orangs and Crab-eating Macaques. These monkeys often associate with Orangs, feeding in the same areas and interacting nonaggressively. Orangs and Crab-eating Macaques may groom each other, and male Orang-utans will occasionally suck the penis of an adult male Crab-eating Macaque.

Transgendered Orang-utans occasionally occur as well: individuals have been found who are physically male yet have a female (XX) chromosome pattern.

Fellatio in two younger male Orang-utans in Sumatra: the male on the lower right is sucking his partner's penis

Frequency: Approximately 9 percent of all Orang-utan sexual encounters in some populations involve males mounting each other; the proportion of same-sex activity is probably even higher, since male oral-genital contacts and female homosexual encounters are not included in this figure. Females who engage in lesbian activity may do so frequently and repeatedly over several days, similar to the repeated sexual interactions in a heterosexual consortship.

Orientation: Male homosexual behavior is characteristic of younger Orang-utans. Not all younger males engage in same-sex activity, but those who do are probably bisexual, since most such individuals are also involved in heterosexual pursuits. Mature adult males probably have a bisexual potential: although they rarely engage in homosexual activity in the wild, in captivity they often do (even in the presence of females). Female Orangs are probably also bisexual — for example, one female who was sexually active with another female later mated heterosexually and raised young. However, while engaged in homosexual behavior, she was exclusively lesbian, since she completely ignored males and focused her attentions entirely on other females.

A female Orang-utan in the forests of Sumatra masturbating with a tool she made from a piece of liana

{287}

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

A wide variety of nonprocreative heterosexual activities are found in Orang-utans. Both males and females often stimulate their partner's genitals with their mouth or hands, and females may also rub their genitals against the male. The female has a prominent clitoris that is stimulated during intercourse, and she often takes the initiative in heterosexual activity, actually mounting the male, manually guiding his penis into her, and performing pelvic thrusts while he lies on his back. A variety of positions are used for heterosexual copulation, including face-to-face (the most common), front-to-back, and sideways. In almost 30 percent of mounts, vaginal penetration and/or ejaculation do not occur. Anal stimulation can be a component of heterosexual interactions as well: both males and females lick, suck, blow on, insert fingers into, and rub their genitals on their partner's anus; males have also been known to engage in anal intercourse (penetration) with females. Females may consort and copulate with multiple male partners, and copulation can occur throughout pregnancy up to the time of birth. Masturbation is also common among Orangs — females rub their fingers or foot on their clitoris or insert a finger or toe into their vagina, while males rub their penises with their fist or foot. Both males and females also use inanimate objects or "tools" to masturbate. Males sometimes become sexually aroused and spontaneously ejaculate during long-calling (a courtship and territorial vocalization used by mature males). Mothers frequently engage in incestuous contact with their infants, manually or orally stimulating the penis or clitoris (or being stimulated by the infant), and may even mount the infants.

Heterosexual relations are sometimes characterized by aggression and violence rather than pleasure and consensuality. Younger males often chase, harass, and rape females. During such interactions, which may account for the majority of copulations in some populations, the male may grab, slap, bite, and forcibly restrain the female, who struggles violently while screaming or whimpering. Occasionally (about 7-8 percent of the time) she does manage to break free. An unusual form of reproductive suppression also occurs among male Orangs. Although they become sexually mature at seven to ten years old, males generally fail to develop the full range of secondary sexual characteristics (such as the large cheek pads or "flanges," a throat pouch, and a general weight increase) for another seven years, and sometimes this is delayed for as long as two decades. It is thought that this development is suppressed by the presence of a mature male, perhaps through social intimidation or stress, although the exact mechanism is not known. Nonbreeding males have been found to have higher estrogen levels than breeding males, so perhaps a physiological effect is also involved. Interestingly, nonflanged younger males have been observed copulating repeatedly with females without resulting in any pregnancies; perhaps this is related to their arrested sexual development, although it is also possible that they were simply mating during the nonovulatory phase of the female's cycle. In addition, adolescent females experience ADOLESCENT STERILITY, lasting a year or longer, during which they can copulate without becoming pregnant. In fact, adolescent females have higher copulation rates than adult females, accounting for more than 60 percent of heterosexual mating. Adult females breed {288}

relatively infrequently, perhaps once every four to eight years. Because females in some populations tend to have synchronized reproductive cycles, there may be periods of up to two years when no adult females are available for mating.

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

* Dutrillaux, B., M.-O. Rethore, and J. Lejeune (1975) "Comparaison du caryotype de l'orang-outang (Pongo pygmaeus) a celui de l'homme, du chimpanze, et du gorille [Comparison of the Karyotype of the Orang-utan to Those of Man, Chimpanzee, and Gorilla]." Annales de Genetique 18:153-61.

Galdikas, B. M. F. (1995) "Social and Reproductive Behavior of Wild Adolescent Female Orangutans." In R. D. Nadler, B. M. F. Galdikas, L. K. Sheeran, and N. Rosen, eds., The Neglected Ape, pp. 183-90. New York: Plenum Press.

--- (1985) "Orangutan Sociality at Tanjung Puting." American Journal of Primatology 9:101-19.

--- (1981) "Orangutan Reproduction in the Wild." In C. E. Graham, ed., Reproductive Biology of the Great Apes, pp. 281-300. New York: Academic Press.

Harrisson, B. (1961) "A Study of Orang-utan Behavior in the Semi-Wild State." International Zoo Yearbook 3:57-68.

Kaplan, G., and L. Rogers (1994) Orang-Utans in Borneo. Armidale, Australia: University of New England Press.

Kingsley, S. R. (1988) "Physiological Development of Male Orang-utans and Gorillas." In J.H. Schwartz, ed., Orang-utan Biology, pp. 123-31. New York: Oxford University Press.

--- (1982) "Causes of Nonbreeding and the Development of the Secondary Sexual Characteristics in the Male Orang Utan: A Hormonal Study." In L. E. M. de Boer, ed., The Orang Utan: Its Biology and Conservation, pp. 215-29. The Hague: Dr W. Junk Publishers.

* MacKinnon, J. (1974) "The Behavior and Ecology of Wild Orang-utans (Pongo pygmaeus)." Animal Behavior 22:3-74.

* Maple, T. L. (1980) Orang-utan Behavior. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Mitani, J. C. (1985) "Mating Behavior of Male Orangutans in the Kutai Game Reserve, Indonesia." Animal Behavior 33:392-402.

* Morris, D. (1964) "The Response of Animals to a Restricted Environment." Symposia of the Zoological Society of London 13:99-118.

Nadler, R. D. (1988) "Sexual and Reproductive Behavior." In J. H. Schwartz, ed., Orang-utan Biology, pp. 105-16. New York: Oxford University Press.

--- (1982) "Reproductive Behavior and Endocrinology of Orang Utans." In L. E. M. de Boer, ed., The Orang Utan: Its Biology and Conservation, pp. 231-48. The Hague: Dr W. Junk Publishers.

* Poole, T. B. (1987) "Social Behavior of a Group of Orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus) on an Artificial Island in Singapore Zoological Gardens." Zoo Biology 6:315-30.

* Rijksen, H. D. (1978) A Fieldstudy on Sumatran Orang Utans (Pongo pygmaeus abelii Lesson 1827): Ecology, Behavior, and Conservation. Wageningen, Netherlands: H. Veenman & Zonen b.v.

Rodman, P. S. (1988) "Diversity and Consistency in Ecology and Behavior." In J. H. Schwartz, ed., Orang-utan Biology, pp. 31-51. New York: Oxford University Press.

Schurmann, C. (1982) "Mating Behavior of Wild Orang Utans." In L. E. M. de Boer, ed., The Orang Utan: Its Biology and Conservation, pp. 269-84. The Hague: Dr W. Junk Publishers.

Schurmann, C., and J. A. R. A. M. van Hooff (1986) "Reproductive Strategies of the Orang-Utan: New Data and a Reconsideration of Existing Sociosexual Models." International Journal of Primatology 7:265-87.

* Turleau, C., J. de Grouchy, F. Chavin-Colin, J. Mortelmans, and W. Van den Bergh (1975) "Inversion peri-centrique du 3, homozygote et heterozygote, et translation centromerique du 12 dans une famille d'orangs-outangs. Implications evolutives [Pericentric Inversion of Chromosome 3, Homozygous and Heterozygous, and Transposition of Centromere of Chromosome 12 in a Family of Orang-utans. Implications for Evolution]." Annales de Genetique 18:227-33.

Utani, S., and T. M. Setia (1995) "Behavioral Changes in Wild Male and Female Sumatran Orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus abelii) During and Following a Resident Male Take-over." In R. D. Nadler, B.M.F. Galdikas, L.K. Sheeran, and N. Rosen, eds., The Neglected Ape, pp. 183-90. New York: Plenum Press.

{289}

Gibbons or Lesser Apes

Gibbons or Lesser Apes

WHITE-HANDED GIBBON (Hybolates lar)

IDENTIFICATION: A small ape (weighing up to 13 pounds) with a variable coat color (cream, black, brown, or reddish) and a white face ring, hands, and feet. DISTRIBUTION: China, Thailand, Laos, Burma, Malay Peninsula, Sumatra. HABITAT: Lowland and mountain deciduous and rain forests. STUDY AREAS: Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, Thailand.

SIAMANG (Hybolates syndactylus)

IDENTIFICATION: Similar to White-handed Gibbon, but larger (up to 24 pounds), with all-black fur and a prominent throat sac. DISTRIBUTION: Sumatra, Malay Peninsula. HABITAT: Lowland and mountain forests. STUDY AREA: Milwaukee County Zoo, Wisconsin.

Social Organization

Gibbons generally live in family groups consisting of a paired male and female and their offspring. Siamang heterosexual pairs may be more closely bonded than those of White-handed Gibbons. Both males and females perform complex vocal duets as part of bonding and territorial displays, although separate family groups have relatively little interaction with one another.

Description

Behavioral Expression: Within their nuclear family groups, male Gibbons sometimes engage in homosexual activities with each other. This incestuous activity often takes place between an adolescent or younger male and his father (or stepfather, if his parents have divorced and re-paired); in Siamangs it may also occur between brothers. A typical homosexual encounter between father and son in White-handed Gibbons occurs in the trees in the morning or early afternoon, while the family is resting or feeding. The mother is generally nonchalant about such encounters, ignoring the sexual activity even if she is close at hand. The two males often groom each other or engage in playful wrestling or chasing as part of their interaction. During such activities, either male may approach the other to initiate sex, which consists primarily of the two males rubbing their erect penises together, {290}

often leading to orgasm. This is done face-to-face (unlike heterosexual copulation, which is typically performed front-to-back). The father lifts up his knees and spreads his legs wide while sitting on a branch or hanging by his arms — this is an invitation to his son to have sex. The adolescent male embraces his father around the waist with his legs, then lowers his body until he is, in effect, sitting in his father's lap, with his legs resting on top of the older male's thighs. This allows their genitals to come into direct contact, and the younger male usually begins rapidly thrusting against his father; sometimes the older male will make pelvic thrusts as well. If his son ejaculates on him, the father may scoop up the semen and eat it. Genital contact can last for up to a minute, although the average is about 20 seconds; in comparison, heterosexual copulations in this species average only about 15 seconds.

A similar form of genital rubbing occurs between father and son in Siamangs. While both males are hanging by their arms, the younger grasps his father around the waist with his legs and both thrust against each other (in this species, heterosexual mating is occasionally also performed face-to-face). Unlike in White-handed Gibbons, this activity is sometimes accompanied by threats between the two males, and it appears that the younger male may on occasion want to terminate the activity before his father does. Sometimes two brothers — juveniles or adolescents, four to nine years old — thrust against each other face-to-face as well. Brothers are also generally affectionate with each other, touching and grooming one another, putting their arms over each other's shoulders, and wrestling together. Fellatio also sometimes occurs in Siamangs: usually an older brother will lick and gently nibble on the penis and groin of his younger brother (who may be only one to three years old) while the latter dangles by his arms above him or sits with his legs spread. The older male may also masturbate the younger by pulling on his erect penis; if ejaculation occurs, the semen may be eaten. Occasionally, a son will lick and groom his father's genital area, or the father might insert one of his fingers into his son's anus.

Frequency: In those Gibbon families where homosexual activity takes place, it occurs quite frequently, and at rates that may equal or exceed heterosexual activity. In one White-handed Gibbon family, the father and son sometimes had sexual encounters as often as 8 times a day — although they averaged about twice a day — and homosexual activity took place on more than a third of the days that the family was observed. In fact, during one 18-day period, 44 homosexual interactions were recorded. In comparison, 23 heterosexual copulations were observed in another family over 18 (different) days, at a rate of 1-3 per day; other studies have found rates of 2 heterosexual matings per day (equivalent to heterosexual activity on about a third of the observation days). In a Siamang family observed in a zoo, about 30 percent of all sexual interactions were between males. It is not yet known, however, in what proportion of families homosexual activity occurs (in either of these species).

Orientation: Male Gibbon sexual life is probably sequentially bisexual, characterized by alternating periods of heterosexual and homosexual activity, with {291}

occasional long-term exclusive homosexuality. Younger males may experience entirely homosexual interactions with their fathers, or sexual activity with both parents (see below) while they are growing up, and then go on to mate heterosexually as adults. Once paired with a female, they may engage in incestuous encounters with their offspring of both sexes or have extended periods of exclusive homosexuality. In one White-handed Gibbon family, no heterosexual interactions were observed between the father and his female mate during the entire two years that homosexual activity was taking place between him and his son.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Like many other species where homosexual activity occurs between related individuals, heterosexual incest is also prominent among Gibbons. Siamang mothers and fathers both interact sexually with their offspring of the opposite sex, as do siblings. Adult males sometimes perform copulation-like thrusting with their daughters, as well as oral and manual stimulation of their genitals. In one case, a Siamang father was observed fondling his adolescent daughter's vulva with his fingers while her younger brother licked her clitoris. Mothers may invite their juvenile sons — as young as four to five years — to lick and groom their genitals (usually with no hostile reaction from the father). When offspring grow up, mother-son pairs (and occasionally, brother-sister pairs) may sometimes develop in both White-handed Gibbons and Siamangs, often when a father dies and is replaced by his son. Nonreproductive sexual behaviors such as oral sex are also commonly performed in non-incestuous contexts, e.g., between a pair-bonded male and female. Cunnilingus (including direct clitoral licking), manual fondling of the vulva, and vaginal penetration with the fingers have all been observed in mated pairs. Females probably also experience orgasm during heterosexual encounters: in one episode in which a male and female were thrusting against each other, a shudder coursed through the female's body, and she remained still for almost half a minute after a period of intense stimulation. Female White-handed Gibbons sometimes masturbate by rubbing their genitals against a surface, and they may experience orgasm this way; male Siamangs also masturbate, though not necessarily to orgasm.

In White-handed Gibbons, about 6-7 percent of heterosexual copulations occur when the female cannot conceive, e.g., during pregnancy or lactation. Some of these matings may be with males other than her mate. Although most Gibbon pairs are monogamous, it is estimated that 10-12 percent of White-handed Gibbon copulations are promiscuous. Nonmonogamous sexual activity also occurs in Siamangs and may be initiated by the female. Similarly, although many Gibbons (of both species) pair for life, divorce also occurs. In one study that followed 11 Gibbon heterosexual pairs over six years, 5 of them split up — usually when one partner left his or her mate to be with another individual. As a result, many White-handed Gibbon families — perhaps up to a third — involve step-parenting. Interestingly, even though there is a wide variety of possible sexual and pairing activities in these species, heterosexual activity is a relatively rare occurrence in wild Gibbons. For example, sexual behavior between male and female White-handed Gibbons generally occurs only once every two years or so, and for periods of only four or five months {292}

at a time when it does (females generally breed only every two to three years). In Siamangs, females go through regular periods of asexuality in which they delay breeding and turn over the care of their young to males. Females of this species look after their young only until they are 12-16 months old; at that time, males assume full responsibility for the offspring, but females do not reproduce again for another year. It is thought that this period of nonreproduction enables them to assume leadership roles in their group.

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

Brockelman, W. Y., U. Reichard, U. Treesucon, and J. J. Raemaekers (1998) "Dispersal, Pair Formation, and Social Structure in Gibbons (Hylobates lar)." Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 42:329-39.

Chivers, D. J. (1974) The Siamang in Malaya: A Field Study of a Primate in Tropical Rain Forest. Contributions to Primatology, vol. 4. Basel: S. Karger.

--- . (1972) "The Siamang and the Gibbon in the Malay Peninsula." In D. M. Rumbaugh, ed., Gibbon and Siamang, vol.1, pp. 103-35. Basel: S. Karger.

Chivers, D. J., and J. J. Raemaekers (1980) "Long-term Changes in Behavior." In D. J. Chivers, ed., Malayan Forest Primates: Ten Years' Study in Tropical Rain Forest, pp. 209-60. New York: Plenum.

* Edwards, A.-M. A. R., and J. D. Todd (1991) "Homosexual Behavior in Wild White-handed Gibbons (Hylobates lar)." Primates 32:231-36.

Ellefson, J. O. (1974) "A Natural History of White-handed Gibbons in the Malayan Peninsula." In D. M. Rumbaugh, ed., Gibbon and Siamang, vol. 3, pp. 1-136. Basel: S. Karger.

* Fox, G. J. (1977) "Social Dynamics in Siamang." Ph.D. thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

--- (1972) "Some Comparisons Between Siamang and Gibbon Behavior." Folia Primatologica 18:122- 39.

Koyama, N. (1971) "Observations on Mating Behavior of Wild Siamang Gibbons at Fraser's Hill, Malaysia." Primates 12:183-89.

Leighton, D. R. (1987) "Gibbons: Territoriality and Monogamy." In B. B. Smuts, D. L. Cheney, R. M. Seyfarth, R. W. Wrangham, and T. T. Struhsaker, eds., Primate Societies, pp. 135-45. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mootnick, A. R., and E. Baker (1994) "Masturbation in Captive Hylobates (Gibbons)." Zoo Biology 13:345- 53.

Palombit, R. (1996) "Pair Bonds in Monogamous Apes: A Comparison of the Siamang Hylobates syndacty-lus and the White-handed Gibbon Hylobates lar." Behavior 133:321-56.

--- (1994a) "Dynamic Pair Bonds in Hylobatids: Implications Regarding Monogamous Social Systems." Behavior 128:65-101.

--- (1994b) "Extra-pair Copulations in a Monogamous Ape." Animal Behavior 47:721-23.

Raemaekers, J. J., and P. M. Raemaekers (1984) "Vocal Interaction Between Two Male Gibbons, Hylobates lar." Natural History Bulletin of the Siam Society 32:95-106.

Reichard, U. (1995a) "Extra-pair Copulation in Monogamous Wild White-handed Gibbons (Hylobates lar)." Zeitschrift fur Saugetierkunde 60:186-88.

--- (1995b) "Extra-pair Copulation in a Monogamous Gibbon (Hylobates lar)." Ethology 100:99-112.

{293}

LANGURS AND LEAF MONKEYS

Langurs

Langurs

HANUMAN LANGUR (Presbytis entellus)

IDENTIFICATION: A medium-sized monkey with a silver-gray or brown coat, black face, slender limbs, and a long tail (over 3 feet). DISTRIBUTION: Throughout India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Burma. HABITAT: Scrub and deciduous forests. STUDY AREAS: Numerous locations in India, including Jodhpur, Abu, Kumaon Hills; Polonnaruwa, Sri Lanka; Melemchi, Nepal; University of California-Berkeley.

NILGIRI LANGUR (Presbytis johnii)

IDENTIFICATION: Similar to Hanuman Langur but with shiny black fur, a light brown hood, and a prominent brow tuft. DISTRIBUTION: Southwestern India; vulnerable. HABITAT: Montane evergreen rain forests, woodlands. STUDY AREAS: Nilgiri district, Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve, Anaimalai Wildlife Sanctuary, India.

Social Organization

Hanuman Langurs live in cosexual troops (some contain only one male) and also in all-male groups. The latter typically include up to 30 or more individuals; about 20 percent of the population in some areas lives in male-only groups. Nilgiri Langurs live in both cosexual troops (usually eight to nine monkeys each, with one or two adult males) and same-sex groupings (usually two or three males, occasionally more, constituting about a quarter to a third of the adult males). Troop life and stability generally revolve around the females; males are distinctly peripheral to the overall social system, playing only a minor role in defending the troop and minimally helping raise the young.

A female Hanuman Langur in India mounting another female

{294}

Description

Behavioral Expression: Homosexual mounting is a prominent feature of female interactions in Hanuman Langurs. One female climbs on the back of another and begins pelvic thrusting. Unlike in other species that engage in homosexual mounting, the female does not rub her genitals on the rump of the other female, but rather thrusts against her buttocks. The mounter may experience indirect stimulation of the area surrounding her clitoris, while the mountee may have direct clitoral stimulation from the female on top of her. In many ways such mounts resemble heterosexual matings, for example in their duration (5 to 10 seconds), number of pelvic thrusts (two to eleven), the grunting and grimacing of the mounter, and the JUMPING DISPLAY, which often precedes or follows. In other respects, however, homosexual mountings are strikingly different. For example, most heterosexual matings are solicited by the female, who lowers her head and shakes it while presenting her hindquarters to the male. While a similar solicitation occurs in about 13 percent of mounts between females, the majority (79 percent) are initiated by the mounting female. In both homosexual and heterosexual mounts, the partners groom following a mount; however, between females the mounter usually grooms the mountee, while in heterosexual mounts, the mountee (female) typically grooms the mounter (male). Finally, only about 30 percent of homosexual mounts are interrupted by other individuals; in contrast, more than 80 percent of heterosexual copulations are harassed by other animals trying to disrupt (and prevent) the mating. Up to seven animals of all ages and sexes may converge on an opposite-sex mating pair and directly attack the animals, slapping them, trying to push the male off or chase the female out from under him, and even kicking the male's testicles.

All females participate freely in homosexual mounting, including lactating, pregnant, menstruating, ovulating, and nonovulating females. This behavior is especially common among mothers, who have developed a special "baby-sitting" system: they transfer their young to other individuals in the troop (usually other females but sometimes males) for a short time (a similar pattern is found in Nilgiri Langurs). This allows them to engage in homosexual (and other) activities. Most mounting between females occurs among adults, though some involves adults with {295}

juveniles (up to four years old), usually with the younger female mounting the older one. Although most homosexual participants are unrelated, some mountings are incestuous, mostly between half sisters (about 27 percent of all lesbian mounts) and, more rarely, between mother and daughter (about 1 percent of mounts); heterosexual matings are virtually never incestuous.

Male Hanuman Langurs mount each other as well, especially in the all-male bands. Unlike homosexual mounting between females, this activity is typically initiated by the mountee, who invites another male to mount him by performing a head-shaking display (sometimes combined with small jumps and "snoring" vocalizations). Mounting often involves one male rubbing and thrusting his erect penis against the other's body and may be accompanied by a number of affectionate activities that are typically associated with sexual arousal. These include embracing (in which one male buries his head in the chest or shoulder of another), mouth-to-mouth contact or "kissing," reciprocal grooming (often accompanied by erections), and touching or grooming of the genitals with the hand or lips. Males also "cuddle," one sitting closely behind the other, resting his head on the back of the male seated between his legs while touching his loins. Hanuman males sometimes form DOUS — companionships in which two males live and travel together, visiting troops in other areas or sometimes settling into all-male bands. Some duos are short-lived (a month or less), others more long-lasting.

Male Nilgiri Langurs also interact erotically with each other in a number of ways, usually incorporating three types of activities: grooming, embracing, and mounting. These are not entirely separate behaviors, and they often combine with each other. Grooming is an intensely pleasurable, relaxing, and arousing experience: one or both males usually get an erection during grooming, and this may lead to ejaculation (a male may even eat his own semen afterward). In embracing, one monkey runs up to another and gives him a long, clinging hug; this is often combined with grooming and has a noticeable soothing effect. Male Nilgiri Langurs also mount each other, using the same position as for heterosexual intercourse. One male may directly approach another male and present his hindquarters to the other, or else he may go through a more stylized presentation known as REAR-END FLIRTATION, in which he slowly walks by the other male and turns his hindquarters toward him as he passes by. During same-sex mounting, one male climbs on top of the other's rump, grabbing the mounted monkey by the ankles with his feet while making pelvic thrusts (often simultaneously mouthing his back); the mountee sometimes looks or reaches back to grasp the other male. Following mounting, the monkeys often groom or embrace-groom. In cosexual troops with more than one male, two males who engage in homosexual mounting may cooperate in launching attacks against males in neighboring groups.