<<< >>>

{339}

Marine Mammals

DOLPHINS AND WHALES

River Dolphins

River Dolphins

BOTO or AMAZON RIVER DOLPHIN (Inia

geoffrensis)

IDENTIFICATION: An 8-foot-long dolphin with a long, toothed beak and light blue or even bright pink skin. DISTRIBUTION: The Amazon and Orinoco River systems; vulnerable. HABITAT: Slow-moving streams and tributaries, flooded forests, lakes. STUDY AREAS: Duisburg Zoo, Germany; Aquarium of Niagara Falls, New York; subspecies l.g. humboldtiana, the Orinoco Dolphin.

Social Organization

Although little is known about their social organization, it appears that Botos are largely solitary animals that occasionally associate in groupings of up to a dozen or more individuals. Larger aggregations generally occur at feeding areas, and Botos may even coordinate their fishing attempts with other species, such as the giant river otter (Pteronura brasiliensis). The Boto mating system is probably polygamous.

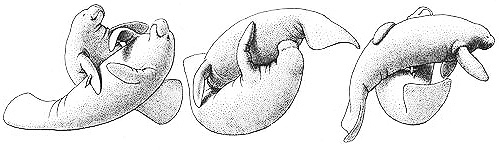

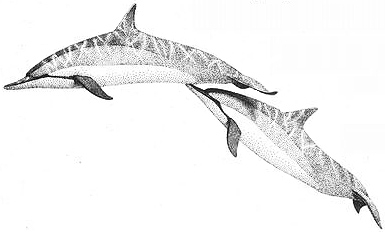

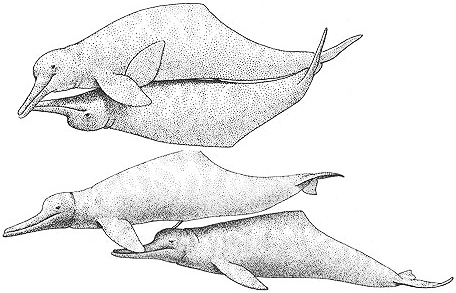

Two forms of copulation between male Botos: genital-slit (or anal) penetration (above) and blowhole penetration

Description

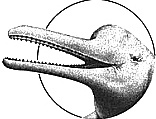

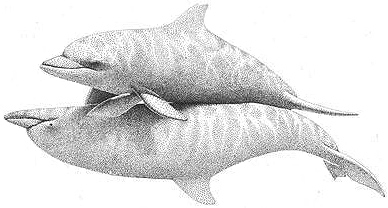

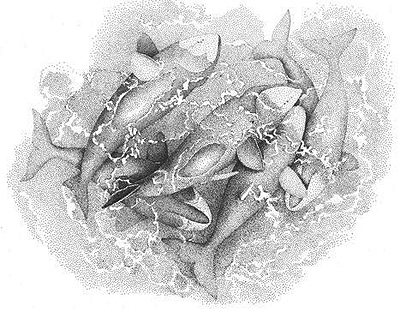

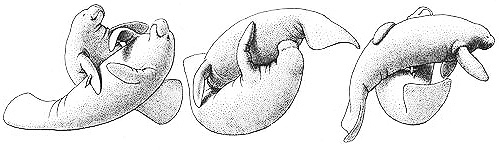

Behavioral Expression: Male Botos participate in a wide variety of homosexual interactions, including mating with each other using fully three different types of penetration: one male may insert his erect penis into the genital slit of the other, into his anus, or into his blowhole. When engaging in anal or genital-slit intercourse, one male swims upside down beneath the other one as in heterosexual copulation; blowhole mating occurs with the inserting male above the other one. If there is an age difference between the males, typically the older one penetrates the younger one. Males also rub their genital openings or erect penises against each other; alternatively, one male might rub his head against the other's genitals, {340}

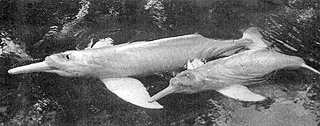

stimulating an erection. Pairs of males who interact sexually also display a great deal of affection toward one another, caressing each other with their beak or flippers, brushing against one another, swimming side by side while touching each other's body, flippers, or flukes, surfacing to breathe simultaneously, or playing and resting together. Male homosexual encounters can be quite lengthy — continuing for a whole afternoon, for example — although if mating occurs, the actual penetration lasts for only about one minute (in anal intercourse).

Male Botos also engage in homosexual activity with another species of Amazon River dolphin, the Tucuxi (Sotalia fluviatilis). In these interspecies encounters, genital slit intercourse between males involves the same belly-to-belly position described above, but sometimes the penetrating animal twists around so that his head faces in the opposite direction (while still remaining inserted in the other male). In addition to caresses and genital rubbing, homosexual activity sometimes includes more unusual behavior: a male Boto was once seen gently taking a Tucuxi's entire head into his mouth, in an apparently affectionate gesture.

Frequency Homosexual activity is common in captive Botos; its prevalence among wild animals is not known. Similarly, sexual behavior between Botos and Tucuxis has only been seen in captivity, but these two species do occasionally interact with one another in the wild.

Orientation: Because homosexual behavior has been studied in detail only in captive male Botos without access to females, it is not known whether this behavior occurs in other contexts, or if it is simply an expression of a latent or "situational" bisexual potential. However, given the varied and generally plastic nature of dolphin sexuality, it is likely that homosexual or bisexual expression is a basic component of Boto social life for at least some individuals.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Male and female Botos sometimes engage in nonreproductive matings: heterosexual blowhole copulations have been observed, and a male will also sometimes rub his penis against the female's fins or flukes, especially if she does not permit him to copulate vaginally. In addition, heterosexual matings can be remarkably frequent and prolonged affairs: {341}

one male and female were seen to mate once every four minutes for a virtually continuous period of over three hours. However, females are not always willing participants in such repeated copulations, often fleeing into shallow waters to avoid males that are harassing them. Females that cannot escape may be attacked and bitten around the genital area by males. Masturbation is also common in Botos: males rub the penis with one of their fins, females sometimes try to insert objects into the genital slit, while both sexes rub their genitals against underwater objects or surfaces. Botos have also developed an alternate parenting or "baby-sitting" arrangement of communal nursery groups. Young Botos gather together in shallow water, forming what are sometimes known as

CRÈCHES that contain both calves and older juveniles; these groups offer them safety in numbers while their parents feed on their own.

Two male Botos, a younger and an older individual who are sexually involved with one another, swimming side by side while touching

Sources (* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

* Best, R. C., and V. M. F. da Silva (1989) "Amazon River Dolphin, Boto, Inia geoffrensis (de Blainville, 1817)." In S. H. Ridgway and R. Harrison, eds., Handbook of Marine Mammals, vol. 4: River Dolphins and the Larger Toothed Whales, pp. 1-23. London: Academic Press.

* Caldwell, M. C., D. K. Caldwell, and R. L. Brill (1989) "Inia geoffrensis in Captivity in the United States." In W. F. Perrin, R. L. Brownell, Jr., Z. Kaiya, and L. Jiankang, eds., Biology and Conservation of the River Dolphins, pp. 35-41. Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission no. 3. Gland, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.

* Caldwell, M. C., D. K. Caldwell, and W. E. Evans (1966) "Sounds and Behavior of Captive Amazon Freshwater Dolphins, Inia geoffrensis." Los Angeles County Museum Contributions in Science 108:1-24.

Layne, J. N. (1958) "Observations on Freshwater Dolphins in the Upper Amazon." Journal of Mammology 39:1-22.

* Layne, J. N., and D. K. Caldwell (1964) "Behavior of the Amazon Dolphin, Inia geoffrensis (Blainville), in Captivity." Zoologica 49:81-108.

* Pilleri, G., M. Gihr, and C. Kraus (1980) "Play Behavior in the Indus and Orinoco Dolphin (Platanista indi and Inia geoffrensis)." Investigations on Cetacea 11:57-107.

* Renjun, L., W. Gewalt, B. Neurohr, and A. Winkler (1994) "Comparative Studies on the Behavior of Inia geoffrensis and Lipotes vexillifer in Artificial Environments." Aquatic Mammals 20:39-45.

* Spotte, S. H. (1967) "Intergeneric Behavior Between Captive Amazon River Dolphins Inia and Sotalia." Underwater Naturalist 4:9-13.

* Sylvestre, J.-P. (1985) "Some Observations on Behavior of Two Orinoco Dolphins (Inia geoffrensis humboldtiana [Pilleri and Gihr 1977]), in Captivity, at Duisburg Zoo." Aquatic Mammals 11:58-65.

Trujillo, F. (1996) "Seeing Fins." BBC Wildlife 14:22-28.

{342}

Dolphins

Dolphins

BOTTLENOSE DOLPHIN (Tursiops truncatus)

IDENTIFICATION: The familiar gray, 10-13-foot-long dolphin. DISTRIBUTION: Worldwide oceans and seas. HABITAT: Coastal, temperate-to-tropical waters. STUDY AREAS: Near Sarasota, Florida; Grand Bahama Island, the Bahamas; Marineland, Florida; Marine World Africa, California; Marineland of the Pacific, California; Port Elizabeth Oceanarium, South Africa; Harderwijk Dolphinarium, the Netherlands; subspecies, T.t. truncatus, the Atlantic Bottlenose; T.t. gilli, the Pacific Bottlenose; and T.t. aduncus, the Indian Ocean Bottlenose.

SPINNER DOLPHIN (Stenella longirostris)

IDENTIFICATION: A 6-foot-long dolphin with a long, slender beak; steep, triangular dorsal fin; dark upperparts and light underparts. DISTRIBUTION: Tropical oceans worldwide. HABITAT: Often in deep, offshore waters. STUDY AREAS: Kealake'akua Bay, Hawaii; Sea Life Park Oceanarium, Hawaii; subspecies S.l. longirostris, the Hawaiian Spinner Dolphin.

Social Organization

Bottlenose Dolphins have a highly developed social system characterized by four basic social units: mother-calf pairs, groups of adolescents (often male-only, or with a preponderance of males), bands of up to a dozen adult females and their young, and adult males in pair-bonds (and less commonly, on their own). Spinner Dolphins may have a more fluid social organization, although coalitions of males can sometimes be recognized, as well as schools of a thousand or more individuals. The heterosexual mating system is poorly understood; however, there are no strong male-female bonds, and animals probably mate with multiple partners.

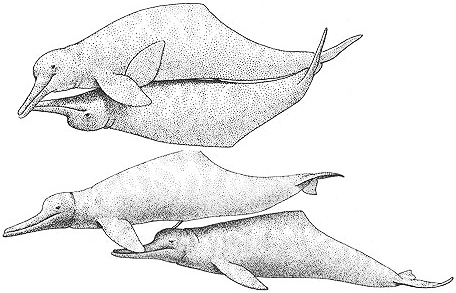

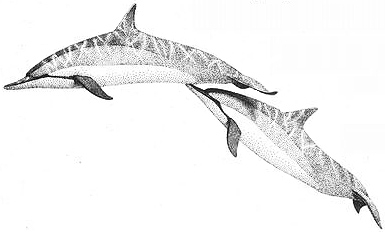

"Beak-genital propulsion" between two female Spinner Dolphins

Description

Behavioral Expression: In both Bottlenose and Spinner Dolphins, animals of the same sex frequently engage in affectionate and sexual activities with each other that have many of the elements of heterosexual courtship and sexuality. For example, two males or two females often rub their bodies together, mouthing and nuzzling one another, and may caress and stroke each other — simultaneously or alternately — with their fins, flukes, snouts (or "beaks"), and heads. Sometimes this is accompanied by playful rolling, chasing, pushing, and leaping. During this activity — {343}

which can last anywhere from several minutes to several hours — males may display erect penises. More overt homosexual activity takes a variety of forms. One animal might stroke or gently probe the other's genital area with the soft tips of its flukes or flippers. Female Spinner Dolphins sometimes even "ride" on each other's dorsal fin — one inserts her fin into the other's vulva or genital slit, then the two swim together in this position. Among Bottlenose females, direct stimulation of the clitoris is a prominent feature of homosexual interactions. Two females often take turns rubbing each other's clitoris, using either the snout, flippers, or flukes, or else actively masturbate against their partner's appendages. Females may also clasp one another in a belly-to-belly position (as in heterosexual mating) and thrust against each other.

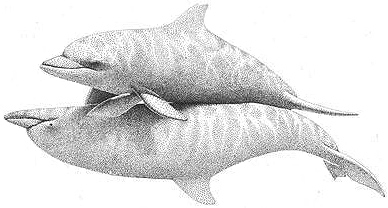

Homosexual interactions also involve a form of "oral" sex in which one animal rubs and nuzzles the other's genitals with its snout or beak; because both males and females have a genital slit or opening, penetration is also possible in this fashion for both sexes. One animal might insert the tip of its beak into the other's genitals or perhaps just use its lower jaw to penetrate and stimulate his or her partner. Sometimes this develops into a sexual activity known as BEAK-GENITAL PROPULSION, in which one partner inserts its beak into the other's genitals and gently propels the two of them forward, maintaining penetration while they swim together. The lower animal may also turn on its side or rotate belly up during this activity. Male Dolphins sometimes rub their erect penises on one another's body or genital area. This may lead to copulation, in which one male swims upside down underneath the other, pressing his genitals against the other and even inserting his penis into the genital slit (or less commonly, anus) of the male above him (this same position is used in heterosexual intercourse). The two partners may switch positions, alternating during the same session, or perhaps exchanging "roles" over a longer period. If there is an age difference between male partners, either may penetrate the other, and Bottlenose adolescents have even been observed penetrating much older males. Groups of three or four males may engage in homosexual activity together, or one male may masturbate (by rubbing his penis on rocks or sand) while other males are coupling nearby. Homosexual activity is sometimes accompanied by aggressive behaviors, but these can also occur during heterosexual interactions (males and females have been observed diving forcefully at each other, for example, and violently ramming their foreheads together as a prelude to mating). In Spinner Dolphins, groups of a dozen or more dolphins of both sexes sometimes gather together in near "orgies" of caressing and sexual behavior (both same-sex and opposite-sex); these groups are known as WUZZLES. {344}

Male Bottlenose Dolphins often form life-long pair-bonds with each other. Adolescent and younger males typically live in all-male groups in which homosexual activity is common; within these groups, a male begins to develop a strong bond with a particular partner (usually of the same age) with whom he will spend the rest of his life. The two Dolphins become constant companions, often traveling widely; although sexual activity probably declines as they get older, it may continue to be a regular feature of such partnerships. Paired males sometimes take turns guarding or remaining vigilant while their partner rests. They also defend their mates against predators such as sharks and protect them while they are healing from wounds inflicted during predators' attacks. Sometimes three males form a tightly bonded trio. On the death of his partner, a male may spend a long time searching for a new male companion — usually unsuccessfully, since most other males in the community are already paired and will not break their bonds. If, however, he can find another "widower" whose male partner has died, the two may become a couple.

Male Bottlenose Dolphins also sometimes aggressively pursue and copulate with male Atlantic Spotted Dolphins (Stenella frontalis), both adults and juveniles. After an initial chase, the Bottlenose male typically arches and rubs his body and erect penis against the Spotted male, then mounts (and often penetrates) him from an upright, sideways position. This mounting position is distinct from the upside-down, belly-to-belly approach generally used for within-species sexual encounters. Sometimes a pair of Bottlenose males pursue a Spotted male and both partners mount him at the same time. Though often playful, this high-energy interspecies homosexual activity may also be accompanied by aggressive behaviors such as tail slaps, threatening postures, and squawking vocalizations (also part of heterosexual interactions between these two species and among Bottlenose Dolphins, as noted above). In fact, groups of Spotted Dolphins — sometimes accompanied by Bottlenose males — may band together to chase off Bottlenose males that are engaging in these more aggressive sexual interactions. However, even when this activity is accompanied by overt aggression, Bottlenose and Spotted males that interact sexually with one another may later also band together and cooperate with one another. Male Atlantic Spotted Dolphins also engage in homosexual activity with each other, and adults sometimes even copulate with male calves of their own species. In one such instance, adult-juvenile homosexual activity was preceded by a vocalization known as a GENITAL BUZZ, in which the adult male directed a stream of low-pitched, rapid {345}

buzzing clicks toward the genital area of the male calf. This sound, which is also a component of heterosexual courtship in this species, may serve as a form of acoustic "foreplay," actually stimulating the genitals of the recipient via the strongly pulsed sound waves. Bottlenose and Spinner Dolphins of both sexes have also been observed participating in homosexual activity with other species of dolphins in captivity, such as Pacific Striped Dolphins (Lagenorhynchus obliquidens), Common Dolphins (Delphinus delphis), Bridled Dolphins (Stenella attenuata), and False Killer Whales (Pseudorca crassidens).

Homosexual copulation in Bottlenose Dolphins: the male in an upside-down position is penetrating the male above him

Frequency: Homosexual interactions are a frequent and regular occurrence in wild Dolphins, particularly among groups of younger Bottlenose males. In mixed-sex groups in captivity, homosexual behavior occurs with equal frequency — and in some cases, more often — than heterosexual activity. Male couples are a ubiquitous feature of many Bottlenose communities; in some cases, more than three-quarters of all males live in same-sex pair-bonds. About 30 percent of interactions between wild Bottlenose and Atlantic Spotted Dolphins include homosexual activities (often accompanied by aggressive behaviors).

Two male Bottlenose Dolphins with erections both attempting to mount a male Atlantic Spotted Dolphin (in the Bahamas) using an upright, sideways mounting position

Orientation: The lives of male Bottlenose Dolphins are characterized by extensive bisexuality, combined with periods of exclusive homosexuality. As adolescents and young males, they have regular homosexual interactions in all-male groups, sometimes alternating with heterosexual activity. From age 10 onward, most male Dolphins form pair-bonds with another male, and because they do not usually father calves until they are 20-25 years old, this can be an extended period — 10-15 years — of principally same-sex interaction. Later, when they begin mating heterosexually, they still retain their primary male pair-bonds, and in some populations male pairs and trios cooperate in herding females or in interacting homosexually with Spotted Dolphins. Because only five or six calves are born to a community each year, however, probably no more than half of the adult males are heterosexually active each mating season (and perhaps far fewer if, as some biologists have suggested, only two or three males monopolize all copulations). Males that do not form same-sex pairs may have a more exclusively heterosexual orientation. Female Bottlenose Dolphins probably have a similar pattern of bisexual interactions {346}

overlaid on a largely female-centered social framework. Spinner Dolphins seem to be more uniformly bisexual without extensive periods of exclusive homosexuality, often alternating between same-sex and opposite-sex interactions in quick succession (this sort of concurrent bisexuality has also been observed in Bottlenose and Atlantic Spotted Dolphins). In captivity, though, Spinners exhibit a continuum, with homosexual activity making up only 10 percent of some individuals' behavior, half to two-thirds for other animals, while some Dolphins interact almost exclusively with animals of the same sex.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Nonprocreative activities are a hallmark of Dolphin heterosexual interactions. Virtually all of the nonreproductive behaviors described above for same-sex interactions also occur between males and females, including beak-genital propulsion and stimulation of the genitals with the flippers, flukes, and snout. Group sexual activity — much of it heterosexual but nonreproductive — occurs in Spinner wuzzles, and courtship and sexual activity in Bottlenose Dolphins sometimes involves up to ten animals at a time. Female sexuality in Dolphins is often pleasure-oriented, focusing on stimulation of the clitoris as much if not more so than vaginal penetration and insemination. Bottlenose Dolphins mate and interact sexually at all times of the year, not just during the mating season; in Spinner Dolphins (and other species as well), males have a yearly sexual cycle, with significant periods when they are probably unable to fertilize females. In addition, masturbation is a prominent feature of Bottlenose sexual life: both males and females rub their genitals against inanimate objects or other animals, sometimes even developing the activity into a playful "game." Females have even been observed using the muscles of their vaginal region to carry small rubber balls, which they then rub their genitals against. Young Dolphins are sexually precocious, and incestuous copulations have been observed between males a few months old and their mothers. Both male and female Bottlenose Dolphins also interact heterosexually with Atlantic Spotted Dolphins, often using the same sideways mounting position and aggressive behaviors described above for interspecies homosexual encounters. Adults often direct sexual behaviors toward juveniles during these interactions, and female Bottlenose Dolphins have even been seen sideways mounting younger male Spotteds (REVERSE mounting). Many heterosexual interactions in captivity also take place between Dolphins of different species.

Interestingly, this broad variety of heterosexual expression takes place in a larger social framework of primarily separate spheres of activity for males and females, at least in Bottlenose Dolphins. As described above, the two sexes are largely segregated for most of their lives, often socializing in same-sex groups. Furthermore, many animals spend a large portion of their lives uninvolved in breeding: most males do not begin mating until they are at least 20 years old (well beyond the time they become sexually mature), and many Dolphins of that age still do not participate in heterosexual mating. Females breed only once every three to six years, and nearly a quarter of the adult female population may not be involved in reproductive activities at any time. When females do bear calves, they are often assisted {347}

by another adult — usually a female — who acts as a "baby-sitter," taking care of the calf while she feeds. Males do not generally parent, and indeed, most Bottlenose calves are sired by males from outside the community. In Spinner Dolphins, "helpers" may be of both sexes, and parental helping behavior has also been observed between Dolphins of different species, for example, by adult Common, Spotted, and Spinner Dolphins toward Bottlenose calves. At times, however, this behavior (within the same species) may be less than "helpful," especially when it involves males. In captivity, "baby-sitting" males have been observed harassing mothers, trying to "kidnap" their calves, and even behaving sexually toward the infants (including trying to mate with them). Pairs and trios of males in some Bottlenose populations also occasionally harass adult females, chasing, herding, and even "kidnapping" and attacking them (e.g., with charges, bites, tail slaps, and body slams) in an attempt to mate with them. Recently, infanticide has also been discovered in some wild Bottlenose communities.

Other Species

Homosexual activity has also been reported in (captive) male Harbor Porpoises (Phocoena phoecena) and Commerson's Dolphins (Cephalorhynchus commersoni), among others. Intersexual or hermaphrodite individuals (possessing external female genitals along with testes and other internal male reproductive organs) occasionally occur in Striped Dolphins (Stenella coeruleoalba).

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

* Amudin, M. (1974) "Some Evidence for a Displacement Behavior in the Harbor Porpoise, Phocoena phocoena (L.). A Causal Analysis of a Sudden Underwater Expiration Through the Blow Hole." Revue du comportement animal 8:39-45.

* Bateson, G. (1974) "Observations of a Cetacean Community." In J. McIntyre, ed., Mind in the Waters, pp. 146-65. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

* Brown, D. H., D. K. Caldwell, and M. C. Caldwell (1966) "Observations on the Behavior of Wild and Captive False Killer Whales, With Notes on Associated Behavior of Other Genera of Captive Delphinids." Contributions in Science (Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History) 95:1-32.

* Brown, D. H., and K. S. Norris (1956) "Observations of Captive and Wild Cetaceans." Journal of Mammalogy 37:311-26.

* Caldwell, M. C., and D. K. Caldwell (1977) "Cetaceans." In T.A. Sebeok, ed., How Animals Communicate, pp. 794-808. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

* --- (1972) "Behavior of Marine Mammals." In S. H. Ridgway, ed., Mammals of the Sea: Biology and Medicine, pp. 419-65. Springfield: Charles C. Thomas.

* --- (1967) "Dolphin Community Life." Quarterly of the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History 5(4):12-15.

* Connor, R. C., and R. A. Smolker (1995) "Seasonal Changes in the Stability of Male-Male Bonds in Indian Ocean Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops sp.)." Aquatic Mammals 21:213-16.

* Connor, R. C., R. A. Smolker, and A. F. Richards (1992) "Dolphin Alliances and Coalitions." In A. H. Harcourt and F. B. M. de Waal, eds., Coalitions and Alliances in Humans and Other Animals, pp. 415-43. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

* Dudok van Heel, W. H., and M. Mettivier (1974) "Birth in Dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in the Dolfinar-ium, Harderwijk, Netherlands." Aquatic Mammals 2:11-22.

* Felix, F. (1997) "Organization and Social Structure of the Coastal Bottlenose Dolphin Tursiops truncatus in the Gulf of Guayaquil, Ecuador." Aquatic Mammals 23:1-16. {348}

* Herzing, D. L. (1996) "Vocalizations and Associated Underwater Behavior of Free-ranging Atlantic Spotted Dolphins, Stenella frontalis and Bottlenose Dolphins, Tursiops truncatus." Aquatic Mammals 22:61-79.

* Herzing, D. L., and C. M. Johnson (1997) "Interspecific Interactions Between Atlantic Spotted Dolphins (Stenella frontalis) and Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in the Bahamas, 1985-1995." Aquatic Mammals 23:85-99.

* Irvine, A. B., M. D. Scott, R. S. Wells, and J. H. Kaufmann (1981) "Movements and Activities of the Atlantic Bottlenose Dolphin, Tursiops truncatus, Near Sarasota, Florida." Fishery Bulletin, U.S. 79:671-88.

* McBride, A. F., and D. O. Hebb (1948) "Behavior of the Captive Bottle-Nose Dolphin, Tursiops truncatus." Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology 41:111-23.

* Nakahara, F., and A. Takemura (1997) "A Survey on the Behavior of Captive Odontocetes in Japan." Aquatic Mammals 23:135-43.

* Nishiwaki, M. (1953) "Hermaphroditism in a Dolphin (Prodelphinus caeruleo-albus)." Scientific Reports of the Whales Research Institute 8:215-18.

* Norris, K. S., and T. P. Dohl (1980a) "Behavior of the Hawaiian Spinner Dolphin, Stenella longirostris." Fishery Bulletin, U.S. 77:821-49.

* --- (1980b) "The Structure and Functions of Cetacean Schools." In L. M. Herman, ed., Cetacean Behavior: Mechanisms and Functions, pp. 211-61. New York: Wiley-InterScience.

* Norris, K. S., B. Wursig, R. S. Wells, and M. Wursig (1994) The Hawaiian Spinner Dolphin. Berkeley: University of California Press.

* Ostman, J. (1991) "Changes in Aggressive and Sexual Behavior Between Two Male Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in a Captive Colony." In K. Pryor and K. S. Norris, eds., Dolphin Societies: Discoveries and Puzzles, pp. 304-17. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Patterson, I. A. P., R. J. Reid, B. Wilson, K. Grellier, H. M. Ross, and P. M. Thompson (1998) "Evidence for Infanticide in Bottlenose Dolphins: an Explanation for Violent Interactions with Harbor Porpoises?" Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series B 265:1167-70.

* Saayman, G. S., and C. K. Tayler (1973) "Some Behavior Patterns of the Southern Right Whale, Eubalaena australis." Zeitschrift fur Saugetierkunde 38:172-83.

Samuels, A., and T. Gifford (1997) "A Quantitative Assessment of Dominance Among Bottlenose Dolphins." Marine Mammal Science 13:70-99.

Shane, S. H. (1990) "Behavior and Ecology of the Bottlenose Dolphin at Sanibel Island, Florida." In S. Leatherwood and R. R. Reeves, eds., The Bottlenose Dolphin, pp. 245-65. San Diego: Academic Press.

Shane, S. H., R. S. Wells, and B. Wursig (1986) "Ecology, Behavior, and Social Organization of the Bottlenose Dolphin: A Review." Marine Mammal Science 2:34-63.

* Tavolga, M. C. (1966) "Behavior of the Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus): Social Interactions in a Captive Colony." In K. S. Norris, ed., Whales, Dolphins, and Porpoises, pp. 718-30. Berkeley: University of California Press.

* Tayler, C. K., and G. S. Saayman (1973) "Imitative Behavior by Indian Ocean Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops aduncus) in Captivity." Behavior 44:286-98.

* Wells, R. S. (1995) "Community Structure of Bottlenose Dolphins Near Sarasota, Florida." Paper presented at the 24th International Ethological Conference, Honolulu, Hawaii.

* --- (1991) "The Role of Long-Term Study in Understanding the Social Structure of a Bottlenose Dolphin Community." In K. Pryor and K. S. Norris, eds., Dolphin Societies: Discoveries and Puzzles, pp. 199-225. Berkeley: University of California Press.

* --- (1984) "Reproductive Behavior and Hormonal Correlates in Hawaiian Spinner Dolphins, Stenella longirostris." In W. E. Perrin, R. L. Brownell, Jr., and D. P. DeMaster, eds., Reproduction in Whales, Dolphins, and Porpoises, pp. 465-72. Report of the International Whaling Commission, Special Issue 6. Cambridge, UK: International Whaling Commission.

* Wells, R. S., K. Bassos-Hull, and K. S. Norris (1998) "Experimental Return to the Wild of Two Bottlenose Dolphins." Marine Mammal Science 14:51-71.

* Wells, R. S., M. D. Scott, and A. B. Irvine (1987) "The Social Structure of Free-ranging Bottlenose Dolphins." In H. Genoways, ed., Current Mammalogy, vol. 1, pp. 247-305. New York: Plenum Press.

{349}

Dolphins

Dolphins

ORGA or KILLER WHALE (Orcinus orca)

IDENTIFICATION: The largest member of the dolphin family (16-26 feet in length); a tall dorsal fin and distinctive black-and-white markings. DISTRIBUTION: Seas and oceans worldwide. HABITAT: Often found in coastal waters. STUDY AREAS: Johnstone Strait, Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada; Puget Sound, Washington.

Social Organization

Killer Whales live in a complex society based on a female-centered social unit called the MATRILINEAL GROUP. This is made up of an adult female, the matriarch — usually reproductively active, but sometimes older and postreproductive — her young, and any adult sons of hers. Sometimes her mother or grandmother is also present, and possibly her brothers or uncles. Matrilineal groups usually contain three or four Orcas (although some have up to nine); these groups are organized into larger social units known as PODS, which tend to socialize together and share a common dialect in their vocalizations. Some populations of Killer Whales are TRANSIENTS, who travel widely in smaller groups (occasionally singly) and are less vocal. Unlike nontransient or RESIDENT Orcas, they feed primarily on marine mammals rather than fish.

Description

Behavioral Expression: Homosexual interactions are an integral and important part of male Orca social life. During the summer and fall — when resident pods join together to feast on the salmon runs — males of all ages often spend the afternoons in sessions of courtship, affectionate, and sexual behaviors with each other. A typical homosexual interaction begins when a male Killer Whale leaves his matrilineal group to join a temporary male-only group; a session can last anywhere from a few minutes to more than two hours, with the average length being just over an hour. Usually only two Orcas participate at a time, although groups of three or four males are not uncommon, and even five participants at one time have been observed. The males roll around with each other at the surface, splashing and making frequent body contact as they rub, chase, and gently nudge one another. This is usually accompanied by acrobatic displays such as vigorous slapping of the {350}

water with the tail or flippers, lifting the head out of the water (SPYHOPPING), arching the body while floating at the surface or just before a dive, and vocalizing in the air. Particular attention is paid by the males to each other's belly and genital region, and often they initiate a behavior known as BEAK-GENITAL ORIENTATION, which is also seen in heterosexual courtship and mating sequences. Just below the surface of the water, one male swims underneath the other in an upside-down position, touching and nuzzling the other's genital area with his snout or "beak." The two males swim together in this position, maintaining beak-genital contact as the upper one surfaces to breathe; then they dive together, spiraling down into the depths in an elegant double-helix formation. As a variation on this sequence, sometimes one male will arch his tail flukes out of the water just before a dive, allowing the other male to rub his beak against his belly and genital area. When the pair resurfaces after three to five minutes, they repeat the sequence, but with the positions of the two males reversed. In fact, almost 90 percent of all homosexual behaviors are reciprocal, in that the males take turns touching or interacting with one another. During all of these interactions, the Orcas frequently display their erect penises, rolling at the surface or underwater to reveal the distinctive yard-long, pink organs. One male may even attempt to insert his penis — which has a prehensile tip that can be independently moved — into the genital slit of another male (although this has yet to be fully verified).

Although males of all ages participate in homosexual activities, this behavior is most prevalent among "adolescent" Orcas (sexually mature individuals 12-25 years old). More than three-quarters of all sessions involve males who are more than five years apart in age, although age-mates also interact together (especially among adolescents). Occasionally, adult-only homosexual activity (i.e., between males 25 years and older) takes place. Some males have favorite partners with whom they interact year after year, and they may even develop a long-lasting "friendship" or pairing with one particular male. Other males seem to interact with a wide variety of different partners. Most participants in homosexual activity come from different matrilineal groups and are therefore not related; however, more than a third of the sessions include brothers or half brothers (along with other participants), while 9 percent are entirely incestuous.

Frequency: Homosexual interactions are common in Orcas during the summer and fall, especially during August and September — anywhere from 6 to 30 or more sessions of same-sex activity may occur each season in some populations. On average, each male participates in one or two sessions each season, spending about 10 percent of his time in this activity; however, some males may be involved in as many as seven or eight sessions and devote more than 18 percent of their time to this behavior. Overall, in some populations more than three-quarters of observed sexual activity occurs between males.

Orientation: Anywhere from one-third to more than one-half of all males engage in homosexual interactions. This behavior is especially prevalent among younger Orcas: adolescent males participate four times more often than adults. {351}

Many males that engage in this behavior are probably bisexual, since they also court and mate with females. However, there are clear differences between individual males in their affinity or "preference" for homosexual interactions: some Killer Whales participate often and actively seek out male partners, while others are much less involved.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Orca communities contain a sizable population of older, nonbreeding females. With an average life span of 50 years — and a possible maximum longevity of 80 years — female Killer Whales can experience a postreproductive period of up to 30 years. In some populations, one-third to one-half of adult females are postreproductive, and it is estimated that a stable population can support as many as two-thirds postreproductive females. Many such females are the matriarchs of their group, and their leadership continues even if it means the ultimate demise of the pod: if there are only male offspring, a pod will eventually disappear upon the death of its matriarch, since there are no breeding females to continue the matriline. Many postreproductive females, while not breeding themselves, act as "baby-sitters" or helpers in an elaborate communal parenting system. They, along with breeding females, nonbreeding adult and adolescent females, and adult males, frequently take care of calves when their mothers are away or attending to a sibling. Since most breeding females reproduce only once every five years, there is a large pool of potential helpers who are not themselves parents in the population. It is estimated that each calf may be baby-sat as often as once a day during particularly busy times. Although postreproductive females no longer procreate, they may still participate in sexual activity, often with younger males. Several other types of nonprocreative heterosexuality also occur among Orcas: pregnant females have been observed engaging in courtship and sexual behavior with males, while heterosexual interactions also occur between adults or adolescents (of both sexes) and youngsters (juveniles as well as calves). Some incestuous sexual activity has also been documented, for {352}

example between an adolescent male and his juvenile sister. Finally, heterosexual interactions do not always involve just two individuals — sometimes a trio of two males and a female will engage in courtship activity together, and one male may even touch and hold the female while the other copulates with her.

Other Species

Same-sex activity occurs in several other species of toothed whales. Pairs of male Sperm Whales (Physeter macrocephalus) that may be homosexually bonded occur in some populations. In the waters surrounding New Zealand, for example, 3-5 percent of males are found in such pairs, probably belonging to a semiresident population. These male couples travel together closely and are usually composed of two adults or one older and one younger male. Sexual interactions leading to orgasm also take place in groups of (primarily younger) male Sperm Whales off the coast of Dominica. Homosexual activity has been seen in captive male Beluga Whales (Delphinapterus leucas) as well. In addition, hermaphrodite individuals occasionally occur in Belugas and possibly also in Sperm Whales. One Beluga, for example, had male external genitalia combined with a complete set of both male and female internal reproductive organs (i.e., two ovaries and two testes).

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

* Ash, C. E. (1960) "Hermafrodite spermhval/Hermaphrodite Sperm Whale." Norsk Hvalfangst-Tidende 49:433.

* Balcomb, K. C. III, J. R. Boran, R. W. Osborne, and N. J. Haenel (1979) "Observations of Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) in Greater Puget Sound, State of Washington." Unpublished report, Moclips Cetologi-cal Society, Friday Harbor, Wash.; 46 pp. (available at National Marine Mammal Laboratory Library, Seattle, Wash.).

* De Guise, S., A. Lagace, and P. Beland (1994) "True Hermaphroditism in a St. Lawrence Beluga Whale (Delphinapterus leucas)." Journal of Wildlife Diseases 30:287-90.

Ford, J. K. B., G. M. Ellis, and K. C. Balcomb (1994) Killer Whales: The Natural History and Genealogy of Orcinus orca in British Columbia and Washington State. Vancouver: UBC Press; Seattle: University of Washington Press.

* Gaskin, D. E. (1982) The Ecology of Whales and Dolphins. London: Heinemann.

* --- (1971) "Distribution and Movements of Sperm Whales (Physeter catodon L.) in the Cook Strait Region of New Zealand." Norwegian Journal of Zoology 19:241-59.

* --- (1970) "Composition of Schools of Sperm Whales Physeter catodon Linn. East of New Zealand." New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 4:456-71.

* Gewalt, W. (1976) Der Weisswal, Delphinapterus leucas [The Beluga]. Wittenberg: A. Ziemsen-Verlag

* Gordon, J., and R. Rosenthal (1996) "Sperm Whales: The Real Moby Dick." BBC-TV productions, UK.

* Haenel, N. J. (1986) "General Notes on the Behavioral Ontogeny of Puget Sound Killer Whales and the Occurrence of Allomaternal Behavior." In B. C. Kirkevold and J. S. Lockard, eds., Behavioral Biology of Killer Whales, pp. 285-300. New York: Alan R. Liss.

* Jacobsen, J. K. (1990) "Associations and Social Behaviors Among Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) in the Johnstone Strait, British Columbia, 1979-1986." Master's thesis, Humboldt State University.

* --- (1986) "The Behavior of Orcinus orca in the Johnstone Strait, British Columbia." In B.C. Kirkevold and J. S. Lockard, eds., Behavioral Biology of Killer Whales, pp. 135-85. New York: Alan R. Liss.

Martinez, D. R., and E. Klinghammer (1978) "A Partial Ethogram of the Killer Whale (Orcinus orca L.)." Carnivore 1:13-27.

Olesiuk, P. F., M. A. Bigg, and G. M. Ellis (1990) "Life History and Population Dynamics of Resident Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) in the Coastal Waters of British Columbia and Washington State." In P. S. Hammond, S. A. Mizroch, and G. P. Donovan, eds., Individual Recognition of Cetaceans: Use of Photo-Identification and Other Techniques to Estimate Population Parameters, pp. 209-43. Report of the International Whaling Commission, Special Issue 12. Cambridge, UK: International Whaling Commission.

* Osborne, R. W. (1986) "A Behavioral Budget of Puget Sound Killer Whales." In B. C. Kirkevold and J. S. Lockard, eds., Behavioral Biology of Killer Whales, pp. 211-49. New York: Alan R. Liss.

Reeves, R. R., and E. Mitchell (1988) "Distribution and Seasonality of Killer Whales in the Eastern Canadian Arctic." In J. Sigurjonsson and S. Leatherwood, eds., North Atlantic Killer Whales, pp. 136-60. Rit Fiskideildar (Journal of the Marine Research Institute, Reykjavik), vol. 11. Reykjavik: Hafrannsok-nastofnunin.

* Rose, N.A. (1992) "The Social Dynamics of Male Killer Whales, Orcinus orca, in Johnstone Strait, British Columbia." Ph.D. thesis, University of California-Santa Cruz.

* Saulitis, E. L. (1993) "The Behavior and Vocalizations of the 'AT' Group of Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) in Prince William Sound, Alaska." Master's thesis, University of Alaska.

* Utrecht, W. L. van (1960) "Notat om den hermafroditte spermhval/Note on the 'Hermaphrodite Sperm Whale.'" Norsk Hvalfangst-Tidende 49:520.

{353}

Baleen Whales

Baleen Whales

GRAY WHALE (Eschrichtius robustrus)

IDENTIFICATION: A baleen whale (fringed plates in the mouth are used to filter food) reaching 38-48 feet in length and 27-37 tons (males are slightly smaller than females); characterized by its grayish color, tufts of bristly hairs on its head, and distinctive white splotches and bumps on skin surface that differ like "fingerprints" for each individual. DISTRIBUTION: West coast of North America from Baja California to Arctic Ocean; from southern Korea and Japan to Sea of Okhotsk. HABITAT: Shallow coastal waters, fjordlike inlets, open oceans. STUDY AREA: Wickaninnish Bay, Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada.

Social Organization

For eight months of the year — during the migration and summering periods — Gray Whales generally travel and socialize in sex-segregated groups (sometimes known as PODS), while for the remaining time the two sexes are together. Gray Whales have one of the longest migration routes of any mammal: they spend their summers feeding in northern waters, while in the fall they head south on a four-month journey to the mangrove lagoons off Baja California where they mate and their calves are born, only to return to their northern waters in the early spring. A few populations of Gray Whales are nonmigratory, remaining year-round in northern waters.

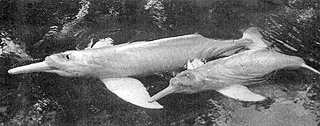

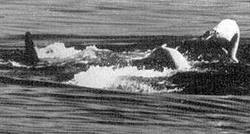

Two male Gray Whales participating in homosexual activity off the coast of Vancouver Island. Only the erect penises of the whales are visible above the surface of the water, but this enabled scientists to verify the sex of the animals. Without this confirmation, observers would probably have mistaken this for heterosexual mating activity.

Description

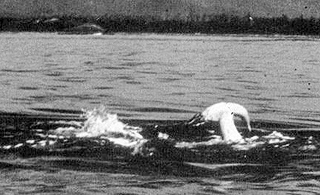

Behavioral Expression: Male homosexual interactions among Gray Whales occur frequently in the northern summering waters and during the northward migration. Sexual and affectionate activities occur close to the surface of the water in long sessions lasting anywhere from 30 minutes to more than an hour and a half. Often more than two males are involved, sometimes as many as four or five. The whales begin by rolling around each other and onto their sides, with much splashing of water, flailing of fins and flukes at the surface, and occasional slapping of the surface and blowing; sometimes two males rise out of the water several feet in a throat-to-throat position. The whales rub their bellies together and position themselves so that their genital areas are in contact, and usually one or more has an arching, erect or semi-erect penis (which is a distinctive light pink in color and may be {354}

three to five feet in length and a foot in circumference at its base). Often two or more males intertwine their penises above the water surface, or one male may lay his erect penis on another male's belly or perhaps nudge the other's penis with his head. Female homosexual interactions may also occur.

Gray Whales also frequently form same-sex companionships (pairs and trios) that travel and feed together throughout the summer (without necessarily engaging in sexual activity with one another). They swim in an intimate side-by-side position, often with their side fins touching, and travel back and forth along the length of coastal inlets for hours at a time, apparently with no particular purpose other than to be together. Such companions also perform synchronized blowing and diving maneuvers, including feeding and BREACHING (an acrobatic leap two-thirds out of the water, landing with a dramatic splash on their sides or backs). Two whales also often roll over and under each other, rubbing bellies. Both short-term and long-term (recurring) pair- and trio-bonds occur: some last only for a few hours or days, with the whales changing partners several times over the summer; other companionships endure from year to year.

Penis intertwining between two male Gray Whales off the coast of

Vancouver Island (the erect organs of the two males are visible above the

surface of the water)

Frequency: Homosexual activity is fairly common in Gray Whales outside the breeding season, and can be seen perhaps as often as five or six times a month in the early spring in some populations. Actual frequencies may be higher, since much sexual activity probably occurs underwater or in locations that are otherwise difficult to observe. At least a quarter of all companion pairs and trios are same-sex.

Orientation: The majority of male Gray Whales are probably bisexual, interacting primarily with each other on the migrations and during the summer in the north, and interacting heterosexually in the calving waters in the south.

{355}

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Migration in Gray Whales involves a lot more than travel: feeding, nursing, and sexual activity all take place during the journey. Migrating pods are separated according to the sex, age, and reproductive status of the whales: on the northward migration, for example, newly pregnant females usually leave first, then adult males, followed by nonovulating and immature females, immature males, and lastly females with new calves. Male Gray Whales also have a distinct seasonal sexual cycle related to sperm production: during the northward migration and the summer months, their testes are essentially inactive, producing little or no sperm; on the southward migration sperm production resumes and peaks in late fall and early winter in preparation for heterosexual breeding. Consequently, for two-thirds of the year, male Gray Whales are nonfertile, even though they sometimes engage in heterosexual copulation during these times. Combined with the female sexual cycle (with its infertile period in the spring and summer) and the fact that sexual interactions outside the mating season may involve groups of whales (not all of whom copulate), this means that a significant portion of heterosexual activity is nonreproductive. Furthermore, heterosexual courtship and copulation during the mating season also sometimes involves groups of up to 18 whales interacting at the same time, and both males and females mate with multiple partners. During the actual mating act, trios consisting of two males and one female are sometimes involved: one male is a "helper" who does not interact sexually with the female, but seems instead to assist the other two to align their bodies and maintain their position during copulation. Females usually breed only every other year, and some wait two years between calves.

Sources (* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

Baldridge, A. (1974) "Migrant Gray Whales with Calves and Sexual Behavior of Gray Whales in the Monterey Area of Central California, 1967-1973." Fishery Bulletin, U.S. 72:615-18.

Darling, J. D. (1984) "Gray Whales Off Vancouver Island, British Columbia." In M. L. Jones, S. L. Swartz, and S. Leatherwood, eds., The Gray Whale, Eschrichtius robustus, pp. 267-87. Orlando: Academic Press.

* --- (1978) "Aspects of the Behavior and Ecology of Vancouver Island Gray Whales, Eschrichtius glaucus Cope." Master's thesis, University of Victoria.

* --- (1977) "The Vancouver Island Gray Whales." Waters: Journal of the Vancouver Public Aquarium 2:4-19.

Fay, F. H. (1963) "Unusual Behavor of Gray Whales in Summer." Psychologische Forschung 27:175-76.

Hatler, D. F., and J. D. Darling (1974) "Recent Observations of the Gray Whale in British Columbia." Canadian Field-Naturalist 88:449-59.

Houck, W. J. (1962) "Possible Mating of Gray Whales on the Northern California Coast." Murrelet 43:54.

Rice, D. W., and A. A. Wolman (1971) The Life History and Ecology of the Gray Whale (Eschrichtius robustus). American Society of Mammalogists Special Publication no. 3. Stillwater, Okla.: American Society of Mammalogists.

Samaras, W. E. (1974) "Reproductive Behavior of the Gray Whale, Eschrichtius robustus, in Baja, California." Bulletin of the Southern California Academy of Sciences 73(2):57-64.

Sauer, E. G. F. (1963) "Courtship and Copulation of the Gray Whale in the Bering Sea at St. Lawrence Island, Alaska." Psychologische Forschung 27:157-74.

Swartz, S. L. (1986) "Demography, Migration, and Behavior of Gray Whales Eschrichtius robustus (Lillje-borg, 1861) in San Ignacio Lagoon, Baja California Sur, Mexico and in Their Winter Range." Ph.D. thesis, University of California-Santa Cruz.

{356}

Right Whales

Right Whales

BOWHEAD WHALE (Balaena mysticetus)

IDENTIFICATION: A black, 50-65-foot whale with a huge head and arched jaw comprising 40 percent of its total length. DISTRIBUTION: Arctic waters of Canada and Greenland; Barents Sea. HABITAT: Ice-edge waters, bays, straits, estuaries. STUDY AREA: Isabella Bay, Baffin Island, Canada.

RIGHT WHALE (Balaena glacialis)

IDENTIFICATION: A 50-60-foot whale weighing up to 104 tons, whose enormous jaws are often encrusted with barnacles and callosites. DISTRIBUTION: Temperate and subarctic waters worldwide; vulnerable. HABITAT: Primarily oceangoing, but closer to land during breeding season. STUDY AREA: Near Valdes Peninsula, Argentina; subspecies B.g. australis, the Southern Right Whale.

Social Organization

Bowhead Whales socialize and travel in small groups of 2-7 animals as well as larger herds of 50-60 individuals; many animals are solitary as well. During much of the year — e.g., the spring migrations, and the socializing and feeding periods of summer and early fall — males and females (as well as different age groups) generally associate separately from each other. Right Whales may form aggregations of 100 or more individuals, although most social interactions occur during the mating period.

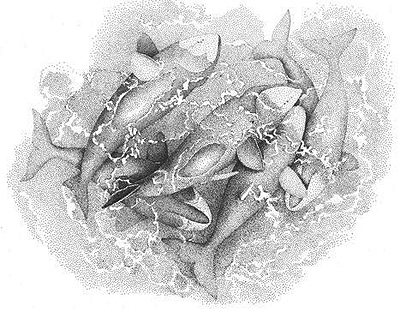

Aerial view of six male Bowhead Whales participating in intensive homosexual activity at the surface of the water; some of the males are displaying erections

Description

Behavioral Expression: Intensive sexual encounters between male Bowhead Whales take place in shallow waters, involving three to six males at a time. Amid much splashing and churning of water, the males roll over each other with erect (unsheathed) penises, caress one another, slap the surface of the water with their tails or flippers, chase each other, and perform TAIL LOFTS, in which the tail is lifted high above the water while the whale sinks vertically down. Generally there is one central whale that the others are trying to copulate with, although this whale often rolls belly up in the water, perhaps attempting to avoid their advances (similar to the behavior of females during heterosexual mating activity). Nevertheless, a male {357}

Bowhead sometimes inserts his penis into the genital slit of another male. Sessions of homosexual activity can last for 40 minutes or more, during which males often produce loud and complex vocalizations that resemble roars, screams, or trumpetings. Both male and female Right Whales also engage in homosexual activity, involving such behaviors as caressing, rolling and pushing, and flipper and fluke slaps.

Bowhead Whales also have a relatively high incidence of intersexual or hermaphrodite individuals with female external genitalia and mammary glands combined with male chromosomes and internal sexual organs such as testes (which are contained within the body cavity in this species, as in other cetaceans).

Frequency: Homosexual activity is characteristic of certain times of the year: in Bowheads, it generally occurs during the late summer and fall, while in Right Whales, it occurs early in the season for females, and late in the season for males. Beyond this, it is difficult to quantify the frequency of same-sex interactions. Among Bowheads, social activity is common during the fall, and about 40 percent of all socializing groups include three or more whales (the configuration typical of sexual interactions). Although the exact percentage of these interactions that are homosexual is not known, in two out of three such groups in which the sexes of all the animals could be determined, the sexual activity involved only males. It is possible, therefore, that a significant proportion of fall sexual activity — perhaps even a majority — is homosexual. Intersexuality in Bowheads is relatively common, occurring in about 1 in 4,000 individuals (compared with a rate of 1 in 62,400 humans for the same type of intersexuality).

{358}

Orientation: In Bowhead Whales, homosexual behavior appears to be typical of adolescent or younger adult males, so it may be that individuals engage in sequential or chronological bisexuality over their lives, with an initial period of homosexuality followed by heterosexuality. This is speculative, however, because the life histories of individual whales have not been tracked. In Right Whales, homosexual behavior is not restricted to younger animals, but in fact occurs among whales of all ages; the extent of heterosexual activities (if any) of such individuals are not fully known.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Because Bowhead and Right Whales generally mate throughout the year — and in particular outside of the female's fertilizable period — a large proportion of heterosexual activity is nonprocreative. In both species, heterosexual copulation usually involves a group of several males trying to mate with one female, who often tries to escape their attentions. At times, the interaction can become violent: groups of male Right Whales searching for females have been described as "rape gangs," and sometimes two or more males cooperate in forcing a female underwater so that they can take turns mating with her. In some cases, calves get caught in the middle of a heterosexual mating attempt and are hit, crushed, and perhaps even killed. Females of these two species generally do not breed every year. In Right Whales, for example, five or more years may elapse between calves, with the result that sometimes less than half of the adult females in an area are breeding.

Other Species

Intersexuality or transgender has also been reported among Fin Whales (Balaenoptera physalus): one individual, for example, had both male and female reproductive organs, including a uterus, vagina, elongated clitoris, and testes.

Sources (* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

* Bannister, J. L. (1963) "An Intersexual Fin Whale Balaenoptera physalus (L.) from South Georgia." Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 141:811-22.

Clark, C. W. (1983) "Acoustic Communication and Behavior of the Southern Right Whale (Eubalaena australis )." In R. S. Payne, ed., Communication and Behavior of Whales, pp. 163-98. American Association for the Advancement of Science Selected Symposium 76. Boulder: Westview Press.

Everitt, R. D., and B. D. Krogman (1979) "Sexual Behavior of Bowhead Whales Observed Off the North Coast of Alaska." Arctic 32:277-80.

Finley, K. J. (1990) "Isabella Bay, Baffin Island, an Important Historical and Present-Day Concentration Area for the Endangered Bowhead Whale (Balaena mysticetus) of the Eastern Canadian Arctic." Arctic 43:137-52.

* Koski, W. R., R. A. Davis, G.W. Miller, and D. E. Withrow (1993) "Reproduction." In J. J. Burns, J. J. Montague, and C. J. Cowles, eds., The Bowhead Whale, pp. 239-74. Lawrence, Kans.: Society for Marine Mammalogy.

* Moore, S. E., and R. R. Reeves (1993) "Distribution and Movement." In J. J. Burns, J. J. Montague, and C. J. Cowles, eds., The Bowhead Whale, pp. 313-86. Lawrence, Kans.: Society for Marine Mammalogy.

* Ostman, J. (1991) "Changes in Aggressive and Sexual Behavior Between Two Male Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in a Captive Colony." In K. Pryor and K. S. Norris, eds., Dolphin Societies: Discoveries and Puzzles, pp. 304-17. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Payne, R. (1995) Among Whales. New York: Scribner.

* Richardson, W. J., and K. J. Finley (1989) Comparison of Behavior of Bowhead Whales of the Davis Strait and Bering/Beaufort Stocks. Report from LGL Ltd., King City, Ontario, for U.S. Minerals Management Service, Herndon, Va.; OCS Study MMS 88-0056, NTIS no. PB89-195556/AS. Springfield, Va.: National Technical Information Service. {359}

* Richardson, W. J., K. J. Finley, G.W. Miller, R. A. Davis, and W. R. Koski (1995) "Feeding, Social, and Migration Behavior of Bowhead Whales, Balaena mysticetus, in Baffin Bay vs. the Beaufort Sea — Regions with Different Amounts of Human Activity." Marine Mammal Science 11:1-45.

Saayman, G. S., and C. K. Tayler (1973) "Some Behavior Patterns of the Southern Right Whale, Eubalaena australis." Zeitschrift fur Saugetierkunde 38:172-83.

* Tarpley, R. J., G. H. Jarrell, J. C. George, J. Cubbage, and G. G. Stott (1995) "Male Pseudohermaphroditism in the Bowhead Whale, Balaena mysticetus." Journal of Mammalogy 76:1267-75.

* Wursig, B., and C. Clark (1993) "Behavior." In J. J. Burns, J. J. Montague, and C. J. Cowles, eds., The Bowhead Whale, pp. 157-99. Lawrence, Kans.: Society for Marine Mammalogy.

* Wursig, B., J. Guerrero, and G. Silber (1993) "Social and Sexual Behavior of Bowhead Whales in Fall in the Western Arctic: A Re-examination of Seasonal Trends." Marine Mammal Science 9:103-11.

{360}

SEALS AND MANATEES

Common or "Earless" Seals

Common or "Earless" Seals

GRAY SEAL (Halichoerus grypus)

IDENTIFICATION: A large seal (up to 7 feet in males) with an elongated muzzle and a spotted coat. DISTRIBUTION: North Atlantic waters, including northeastern North America (especially Newfoundland), Iceland, British Isles, Norway, Kola Peninsula, Baltic Sea. HABITAT: Temperate and subarctic waters; breeds and molts on rocky coasts and islands. STUDY AREA: Ramsay Island, England.

NORTHERN ELEPHANT SEAL (Mirounga angustriostris)

IDENTIFICATION: One of the largest seals, reaching a length of up to 16 feet and a weight of 5,500 pounds (in males); adult males have a prominent proboscis. DISTRIBUTION: North Pacific waters from Alaska to Baja California. HABITAT: Oceangoing; breeds and molts on islands and coasts. STUDY AREA: Ano Nuevo State Reserve, California.

HARBOR SEAL (Phoca vitulina)

IDENTIFICATION: A smaller, round-headed seal with grayish brown, usually spotted fur. DISTRIBUTION: Waters of the North Atlantic and North Pacific. HABITAT: Coastal reefs, sandbars, rocks. STUDY AREAS: Otter Island, Pribilof Islands, Alaska; Nanvak Bay, Cape Newenham National Wildlife Refuge, Alaska; Seaside Aquarium, Oregon; subspecies P.v. richardsi, the Pacific Harbor Seal.

A herd of male Gray Seals hauled out on land during the molting period on Ramsay Island (England). Just before this picture was taken, the two bulls at the water's edge near the large rock were engaging in homosexual activity — a common pursuit among males of all ages at this time of year. Although a few females may be present in these spring haul-outs, they are largely ignored by the males, demonstrating that their homosexual activity is not simply a "substitute" for heterosexual mating.

Social Organization

Gray Seals are highly gregarious, congregating in large colonies for mating and molting, and in large groups to feed. In some populations the mating system is primarily polygynous, meaning that males mate with multiple partners, do not form {361}

heterosexual pair-bonds, and do not participate in parenting. However, some individuals in these areas are "monogamous" in that they mate with the same partner year after year, while in other populations the majority of individuals mate with only one partner but not necessarily the same one each year. Northern Elephant Seals are more solitary when at sea, although they form large breeding and molting aggregations in traditional areas known as ROOKERIES and also have a polygynous mating system. Harbor Seals generally congregate in mixed-sex groups on land, anywhere from a dozen to several thousand animals; they often mate in the water, however, and appear to have a polygynous mating system as well.

Two male Harbor Seals "pair-rolling" (a courtship and sexual behavior)

Description

Behavioral Expression: During the nonbreeding season, both Gray Seal and Northern Elephant Seal bulls engage in homosexual activity. Gray Seals come ashore to molt their fur, gathering in groups of up to 150 animals, no more than half a dozen of which are females. Those males who have completed their molt often roll around in pairs near the water and mount each other; bulls of all ages participate in this activity. Both adolescent and younger adult Northern Elephant Seal bulls also engage in homosexual mounting during the molt period. This occurs in shallow waters near the shore, often as a part of extended bouts of harmless play-fighting among clusters of males. Prior to and during the mating season, this activity continues among adolescent males, though it is usually no longer aquatic. Adolescent males often spend time in male-only areas that are separate from the breeding grounds. Males are attracted to the play-fighting and mounting activity in these areas and may travel up to 100 yards through the rookery to join in. Adult bulls do not participate in this activity. However, they do sometimes mount younger adolescent and juvenile males (two to four years old). Typically the older male approaches a younger male at rest, moving up alongside him and sometimes placing his front flipper over his back in the position characteristic of heterosexual copulations. Usually the younger male struggles to escape, and the mounter may try to subdue him by pressing or bouncing his neck down on top of him or biting his neck. The older male may have an erection and attempt to penetrate the younger male, but he rarely if ever succeeds. Although they prefer juveniles or adolescents, a few bulls also try to copulate with much younger animals, such as weaned pups of both sexes (who strongly resist their advances).

Homosexual activity is also prevalent in male Harbor Seals in the form of PAIR-ROLLING: two males embrace and mount each other in the water, continuously twisting and writhing about one another while maintaining full body contact. Rolling can become quite vigorous as the two animals spiral synchronously underwater and at the surface (often in a vertical position), sometimes gently mouthing or biting each other's neck, chasing each other's flippers, yelping and snarling, blowing streams of bubbles underwater, or slapping the surface of the water. One male usually has an erection, and the bout of courtship rolling typically ends when he mounts the other male, grasping him from behind and maintaining this position for up to 3 minutes (sometimes sinking to the bottom in shallower waters). The two males may also take turns mounting each other. Heterosexual copulations, {362}

in contrast, can occur both in the water and on land; they are not usually accompanied by pair-rolling and can last for up to 15 minutes. Although males of all ages engage in pair-rolling, most participants are adults (sexually mature individuals over six years old) or adolescents.

Same-sex courtship or sexual behavior is not found among females in these species, but two cow Seals occasionally coparent a pup. In Northern Elephant Seals, for example, two females who have each lost their own pup sometimes adopt an orphan and raise it together, or (more commonly) a cow who has lost her pup associates with a mother and shares parenting duties with her, including nursing the pup.

Finally, some adolescent Northern Elephant Seal males are transvestite, acting and looking like females. They have the body proportions of cow Seals, and they also deliberately pull in their noses so that they resemble females (who do not have the enlarged snouts that bulls do) and keep their heads low so as not to attract attention. Moving stealthily through the breeding grounds, these younger males try to copulate with females, who, nevertheless, are usually not fooled by their attempts to disguise themselves and usually do not allow them to mate. However, because most adult males are not able to mate with females, some transvestite males are actually more successful at breeding than non-transvestite males.

Frequency: Homosexual activity occurs frequently in Harbor Seals during the late spring, summer, and fall (except during the pupping season). In one two-month study period, for example, pair-rolling between males occurred daily and in total nearly 285 same-sex rolling pairs were observed (during the same period, no heterosexual matings were seen). Homosexual behavior is also common among male Gray Seals during the molting period, less frequent among Elephant Seal bulls (though it occurs at more times of the year in the latter species). Among females, approximately 2 percent of Elephant Seal adoptive families involve two pupless females coparenting orphaned pups, and another 14 percent involve one female sharing the care of a pup with its mother. Overall, these two-mother families probably represent about 2-3 percent of all families (the remainder are single-mother).

Orientation: Male Gray Seals exhibit seasonal bisexuality: during the molting period, many bulls participate in preferential homosexual activity — generally ignoring any females present in the herd — while during the mating season heterosexual {363}

behavior is the norm. However, only about a third of older males actually copulate with females, while less than 2 percent of younger males (up to eight years old) regularly have access to females. Thus, many bulls probably engage exclusively in homosexual activity for at least part of their lives. Younger adolescent male Elephant Seals — who make up 25-55 percent of the male population — may participate primarily in homosexual mounting, since few actually mate with females. At the other extreme, the highest-ranking bulls are probably exclusively heterosexual, since their attentions are usually directed toward mating (often with hundreds of females each season). Some older adolescent males (40-55 percent of the population) or younger adults may be bisexual, mounting both males and females. However, since less than 9 percent of all males ever mate with females during their lifetime, and less than half of those males surviving to breeding age ever mate, a large number may participate only in same-sex activity (as in Gray Seals). Bulls who mount pups — only a fraction of the male population — do so with equal frequency on both male and female pups. In Harbor Seals, males participate in pair-rolling activity with one another even in the presence of receptive females and generally do so for several months each year (heterosexual mating is usually restricted to a shorter period, perhaps a month or so). Similar patterns of sexual orientation among different age classes probably occur in this species as in the other two.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Gray, Harbor, and Northern Elephant Seals engage in a wide variety of nonprocreative heterosexual behaviors. Sexual activity during pregnancy is not uncommon. When female Gray Seals come ashore just before their pups are born, for example, they often participate in heterosexual copulation and other sexual interactions with males, including REVERSE mountings (in which they mount the male rather than vice versa). Male Northern Elephant Seals also mate with pregnant females, including cows who are leaving the breeding grounds after having already been inseminated. Gray and Harbor Seals sometimes copulate outside of the mating season when fertilization is impossible — not only because the females are pregnant, but because (in Grays) males have their own sexual cycle that renders their testes inactive at that time. Heterosexual matings also occasionally occur between these two species. In addition, females in all three species may copulate with multiple male partners.

As noted above, some male Northern Elephant Seals try to copulate with weaned pups — about half of all pups are subjected to such forced mating or rape attempts, which they usually violently resist. In some cases the pups are severely injured by the bulls, with deep gashes and punctures from neck bites. Aggressive sexual behavior by bulls is the leading cause of mortality among pups on the breeding grounds, accounting for the deaths of about 1 in 200 pups each year. Male Northern Elephant Seals also sometimes aggressively mount pups of other species such as Harbor Seals. Similar aggression, violence, and attempted rape — sometimes lethal — is also directed by bulls toward adult females and adolescents. During mating, male Northern Elephant Seals routinely bite, pin down, and slam the full weight of their bodies against females (bulls are 5-11 times heavier than {364}

females). A female may be pursued by groups of males as she leaves the rookery, sometimes being raped three to seven times as she tries to escape. Some bulls even try to mate with dead females that have been killed during such attacks (and even with dead seals of other species). Mating in Harbor Seals may also involve aggressive attacks by males, female refusal, and even "gangs" of two or three males forcibly copulating with a female. In addition, Gray and Harbor Seal pups are sometimes killed by adults (accounting for about 7 percent of Gray Seal pup deaths), while roughly 6 percent of Harbor Seal pups are abandoned by their mothers shortly after birth.

For much of the year, the two sexes lead largely segregated lives: Northern Elephant Seal males and females, for example, each embark on their own epic migratory journeys twice a year. Males travel farther north to Alaska while females journey out into the central Pacific, remaining separate for up to 300 days as they traverse more than 13,000 miles in their double migrations. Male Gray Seals are at sea (or molting on land) essentially separate from females for nine to ten months of the year. This segregation is facilitated in part by the phenomenon of DELAYED IMPLANTATION, in which a female's fertilized embryo remains in "suspended animation" for three to four months, extending the duration of the pregnancy to eleven or more months. Even during the breeding season, many males do not copulate or reproduce: usually only 14-35 percent of the males present on the breeding grounds mate each season. Likewise, more than 90 percent of male Elephant Seals never copulate during their entire lives (most delay breeding until fairly late and simply perish before reaching the age when reproduction usually begins). Because a small number of individuals often monopolize mating opportunities, some populations may experience high levels of inbreeding. In addition, about 20 percent of females skip breeding each year in some populations.

Separation of the sexes continues through pup-rearing: like most polygamous animals, male Seals do not participate in any parenting duties. Females, however, engage in an assortment of fostering activities, often after they have lost their own pup (although some take care of other pups in addition to their own). More than half of all Northern Elephant Seal pups become separated from their mothers each season, and about 18 percent of all females adopt pups. Besides the female coparenting arrangements mentioned above, many females adopt orphan pups on their own, some female Elephant Seals nurse several orphans at once, while others nurse already weaned pups (who become bloated from the extra milk, turning into gigantic "superweaners," as they are called). Some females even try to "kidnap" or steal pups away from their own mothers, and females who have not lost their own pup often threaten, attack, and even kill stray pups. As many as a quarter to three-quarters of female Gray Seals and 10 percent of female Harbor Seals participate in foster-parenting in some populations.

Other Species

Pairs of female Spotted or Larga Seals (Phoca largha) occasionally coparent their pups together, even sharing in nursing their offspring. Male Sea Otters (Enhydra lutris) have been observed clasping and mounting other males (in the water) in {365}

the position usually seen during heterosexual matings. Male Sea Otters also sometimes mount and attempt to mate with Seals, including Harbor Seals and Northern Elephant Seals, and some of these interactions may be same-sex.

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

Allen, S. G. (1985) "Mating Behavior in the Harbor Seal." Marine Mammal Science 1:84-87.

Amos, B., S. Twiss, P. Pomeroy, and S. Anderson (1995) "Evidence for Mate Fidelity in the Gray Seal." Science 268:1897-99.

Anderson, S. S. (1991) "Gray Seal, Halichoerus grypus." In G. B. Corbet and S. Harris, eds., The Handbook of British Mammals, pp. 471-80. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications.

Anderson, S. S., and M. A. Fedak (1985) "Gray Seal Males: Energetic and Behavioral Links Between Size and Sexual Success." Animal Behavior 33:829-38.

* Backhouse, K. M. (1960) "The Gray Seal (Halichoerus grypus) Outside the Breeding Season: A Preliminary Report." Mammalia 24:307-12.

--- (1954) "The Gray Seal." University of Durham Medical Gazette 48:9-16.

* Backhouse, K. M., and H. R. Hewer (1957) "Behavior of the Gray Seal (Halichoerus grypus Fab.) in the Spring." Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 129:450.

Baker, J. R. (1984) "Mortality and Morbidity in Gray Seal Pups (Halichoerus grypus)." Journal of Zoology, London 203:23-48.

Bishop, R. H. (1967) "Reproduction, Age Determination, and Behavior of the Harbor Seal, Phoca vitulina L. in the Gulf of Alaska." Master's thesis, University of Alaska.

Boness, D. J., D. Bowen, S. J. Iverson, and O. T. Oftedal (1992) "Influence of Storms and Maternal Size on Mother-Pup Separations and Fostering in the Harbor Seal, Phoca vitulina." Canadian Journal of Zoology 70:1640-44.

Boness, D. J., and H. James (1979) "Reproductive Behavior of the Gray Seal (Halichoerus grypus) on Sable Island, Nova Scotia." Journal of Zoology, London 188:477-500.

Burton, R. W., S. S. Anderson, and C. F. Summers (1975) "Perinatal Activities in the Gray Seal (Halichoerus grypus)." Journal of Zoology, London 177:197-201.

Coulson, J. C., and G. Hickling (1964) "The Breeding Biology of the Gray Seal, Halichoerus grypus (Fab.), on the Farne Islands, Northumberland." Journal of Animal Ecology 33:485-512.

* Deutsch, C. J. (1990) "Behavioral and Energetic Aspects of Reproductive Effort of Male Northern Elephant Seals (Mirounga angustirostris)." Ph.D. thesis, University of California-Santa Cruz.

* Hatfield, B. B., R. J. Jameson, T. G. Murphey, and D. D. Woodard (1994) "Atypical Interactions Between Male Southern Sea Otters and Pinnipeds." Marine Mammal Science 10:111-14.

Hewer, H. R. (1960) "Behavior of the Gray Seal (Halichoerus grypus Fab.) in the Breeding Season." Mammalia 24:400-21.

Hewer, H. R., and K. M. Backhouse (1960) "A Preliminary Account of a Colony of Gray Seals, Halichoerus grypus (Fab.) in the Southern Inner Hebrides." Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 134:157-95.

Hoover, A. A. (1983) "Behavior and Ecology of Harbor Seals (Phoca vitulina richardsi) Inhabiting Glacial Ice in Aialik Bay, Alaska." Master's thesis, University of Alaska.

* Johnson, B.W. (1976) "Studies on the Northernmost Colonies of Pacific Harbor Seals, Phoca vitulina richardsi, in the Eastern Bering Sea." Unpublished report, University of Alaska Institute of Marine Science and Alaska Department of Fish and Game; 67 pp. (available at National Marine Mammal Laboratory Library, Seattle, Wash.).

* --- (1974) "Otter Island Harbor Seals: A Preliminary Report." Unpublished report, University of Alaska Institute of Marine Science and Alaska Department of Fish and Game; 20 pp. (available at National Marine Mammal Laboratory Library, Seattle, Wash.).

* Johnson, B. W., and P. Johnson (1977) "Mating Behavior in Harbor Seals?" Proceedings (Abstracts) of the Conference on the Biology of Marine Mammals (San Diego) 2:30.

Kroll, A. M. (1993) "Haul Out Patterns and Behavior of Harbor Seals, Phoca vitulina, During the Breeding Season at Protection Island, Washington." Master's thesis, University of Washington.

* Le Boeuf, B. J. (1974) "Male-Male Competition and Reproductive Success in Elephant Seals." American Zoologist 14:163-76.

--- (1972) "Sexual Behavior in the Northern Elephant Seal, Mirounga angustirostris." Behavior 41: 1-26.

Le Boeuf, B. J., and R. M. Laws (eds.) (1994) Elephant Seals: Population Ecology, Behavior, and Physiology. Berkeley: University of California Press. {366}

Le Boeuf, B. J., and S. Mesnick (1991) "Sexual Behavior of Male Northern Elephant Seals: I. Lethal Injuries to Adult Females." Behavior 116:143-62.