<<< >>>

{378}

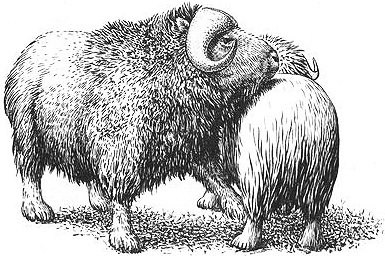

Hoofed Mammals

DEER

Deer

Deer

WHITE-TAILED DEER (Odocoileus virginianus)

IDENTIFICATION: A medium-sized deer (approximately 3 feet tall at shoulder) with a white undertail and multipronged antlers that sweep forward. DISTRIBUTION: Southern Canada, United States except Southwest, Mexico south to Bolivia and northeastern Brazil. HABITAT: Varied, from thickets to open country. STUDY AREAS: Welder Wildlife Refuge, Sinton, Texas; Edwards Plateau, Llano County, Texas; subspecies 0.v. texanus, the Texas White-tailed Deer.

MULE or BLACK-TAILED DEER (Odocoileus hemionus)

IDENTIFICATION: A stocky, grayish deer with a black-tipped tail and antlers that branch into two equal portions. DISTRIBUTION: Western North America, northern Mexico. HABITAT: Semiarid forest, brushlands. STUDY AREAS: Waterton and Banff National Parks, Alberta, Canada; University of British Columbia, Canada; near Fort Collins, Colorado; subspecies O.h. hemionus, the Rocky Mountain Mule Deer, and O.h. columbianus, the Black-tailed Deer.

Social Organization

During most of the year, White-tailed and Mule Deer live in sex-segregated groups: females form groups with other does and their offspring, while males (bucks) live in "bachelor" groups or on their own. During the rutting season, males form short-lived, consecutive "tending bonds" with multiple females — a form of polygamy or "serial monogamy." Larger cosexual groups may also form during the winter.

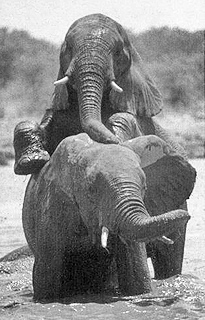

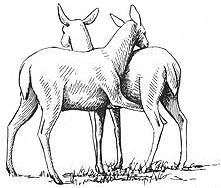

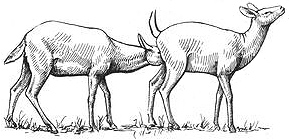

A male White-tailed Deer mounting another buck

{379}

Description

Behavioral Expression: Adult male White-tailed Deer sometimes mount each other, as do yearling males (especially during the nonbreeding season); occasionally a younger male mounts an older one during this activity. Homosexual mounts (like heterosexual ones) are usually preceded by one male nuzzling the other's rear end, and sometimes one male mounts another twice in a row; occasionally the mounting buck has an erection. The mount may be briefer than a male-female copulation, but the same duration as heterosexual nonreproductive mounts (5-15 seconds, as opposed to 15-20 seconds). Yearling Mule Deer occasionally mount each other during SPARRING MATCHES — ritualized, nonviolent contests in which the bucks lock horns. During this activity one male might assume a stiffened posture, similar to a female's before copulation. The other male — sometimes younger or smaller than the first — then mounts him, after first licking and smelling the special scent-producing glands on his hind legs. Female Mule Deer also sometimes mount each other when in heat; in addition, some does court other females using a chasing sequence known as RUSH COURTSHIP. In this behavior (which also occurs in heterosexual contexts), they race toward another female, stopping abruptly and sometimes pawing the ground, pacing, leaping into the air while twisting their body, or running in circles or figure eights; this causes the other doe to become excited and aroused. Adult male White-tailed Deer frequently develop "companionships" or bonds with one (or occasionally two) other adult males in their buck groups; male companions are generally not related to each other. These strong attachments constitute the stable "core" of each buck group, and although male companions typically separate during the breeding season, they usually resume their bonds once mating is over.

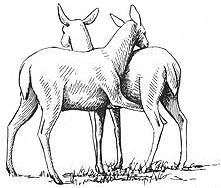

An extraordinary form of transgendered deer occurs in some populations of White-tails. These animals, which are genetically male but actually combine characteristics of both males and females, are sometimes called VELVET-HORNS because their antlers are permanently covered with the special "velvet" skin that in most males is shed after the antlers have grown. Their antlers are usually only spikes (without the extensive branching of other males' antlers) and they slope backward and sometimes have enlarged bases. Physically, velvet-horns often have body proportions and facial features more typical of does, while their testes are small and undeveloped (and in fact the {380}

animals are infertile). A similar type of transgender is found among Mule Deer, where the animals are known as CACTUS BUCKS owing to the distinctive shape of their antlers (which sometimes also have elaborate spikes, prongs, and asymmetrical growths). Velvet-horns usually form their own social groups of three to seven animals and live separately from both does and nontransgendered males. In fact, they are often harassed and attacked by other deer. Nontransgendered White-tails (both does and bucks of all ages, even fawns) threaten velvet-horns who try to approach them — forcing them to remain no less than ten feet away — while bucks may actively charge velvet-horns to drive them away. When threatened, velvet-horns flee without giving the standard alarm signals of other deer (stamping their feet, snorting or whistling, and raising their tails). Sometimes, groups of up to six bucks "gang up" on a velvet-horn, chasing and even violently attacking it by gashing its rump with their antlers. As a result, velvet-horns are extremely wary around other deer, venturing near feeding areas cautiously and always remaining in groups on the periphery, or else refusing to approach at all when other deer are present. Interestingly, velvet-horns are almost always in superior physical condition compared to nontransgendered males, precisely because they do not breed. The rutting season is extremely taxing on breeding bucks, who rarely eat and may lose up to a quarter of their body weight. In contrast, velvet-horns consistently have excellent body fat deposits and are in prime shape.

Two types of gender-mixing females also occur among White-tailed and Mule Deer, both bearing antlers (females in these species do not usually have antlers). In one type, the antlers are similar to those of velvet-horns: they are permanently covered in velvet, are never shed, and are either spikes or asymmetrically branching. Unlike velvet-horns, such females are usually fertile, mating heterosexually and becoming mothers. The other type is a more complete form of intersexuality: the antlers are hard and polished, more closely resemble those of males in their branching structure, and may even be shed seasonally. These individuals usually combine both male and female sexual traits, such as having the genitalia and/or reproductive organs of both sexes, or partial organs of each sex, or chromosomes of one sex combined with the genitalia of the other.

A transgendered "velvet-horn" White-tailed Deer

Frequency: Homosexual mounting probably occurs only occasionally among White-tailed and Mule Deer; however, in one study of White-tails, two out of ten observed mountings were same-sex. Up to 10 percent of males are velvet-horns in some areas, although their incidence fluctuates. In some years they may constitute as many as 40-80 percent of all males in a given population. One study of a {381}

White-tailed Deer population over 14 years found that 1-2 percent of the females had antlers; overall, approximately 1 in every 1,000-1,100 does is antlered.

Orientation: Most Deer that participate in same-sex mounting probably also engage in heterosexual courtship and copulation. Gender-mixing Deer that are fertile (almost always genetically female) are usually heterosexual (i.e., they mate with genetic males), while nonfertile transgendered Deer (e.g., velvet-horns) are probably asexual or associate only with other transgendered Deer.

Sex for pleasure: masturbation in a White-tailed Deer

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Deer participate in a variety of nonprocreative sexual behaviors besides homosexuality. White-tails sometimes engage in heterosexual mountings outside of the mating season, which are nonreproductive for two reasons. They often do not involve penetration, and bucks have a seasonal sexual cycle, so that during the spring and summer their testes are small and produce little, if any, sperm. Mating episodes among Mule Deer during the breeding season often involve the male performing extensive non-insertive sexual activity prior to actual copulation: in this activity he mounts the female with his penis erect (unsheathed) but without penetration. These mounts may be fairly lengthy — up to 15 seconds — and frequent (anywhere from 5 to more than 40 in one session). Bucks of both species sometimes masturbate in a unique fashion: the penis is first unsheathed and licked, then stimulated by moving it back and forth (via pelvic rotations and thrusts) in its sheath or against the belly until orgasm is reached. Because their antlers are actually sensitive — even erotic — organs (as in several other species of Deer), buck Mule Deer also sometimes sexually stimulate themselves by rubbing their antlers on vegetation. Incestuous activity — including fawns mounting their mothers — also occurs in these species.

As mentioned above, sex segregation is a notable feature of White-tailed Deer society. This pattern usually begins during the fawning period, when does become aggressive toward adult males and may even kick and chase them away. When their male fawns become yearlings, females also drive them away in the same violent fashion. In addition to nonbreeding transgendered animals, other nonreproducing individuals occur. White-tail bucks often do not mate until they are three to five years old; because of the physical stresses of reproduction, bucks that delay breeding may actually grow larger than those that reproduce earlier. When breeding does occur, females of both species sometimes terminate their pregnancies by aborting the fetus or reabsorbing the embryo. This probably occurs in 1-10 percent of Mule Deer pregnancies, but is more likely to happen when unfavorable climate and forage would make it difficult for mothers to feed and care for their young.

Sources (* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

* Anderson, A. E. (1981) "Morphological and Physiological Characteristics." In O. C. Wallmo, ed, Mule and Black-tailed Deer of North America, pp. 27-97. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press.

* Baber, D. W. (1987) "Gross Antler Anomaly in a California Mule Deer: The 'Cactus' Buck." Southwestern Naturalist 32:404-6. {382}

Brown, B. A. (1974) "Social Organization in Male Groups of White-tailed Deer." In V. Geist and F. Walther, eds., The Behavior of Ungulates and Its Relation to Management, vol. 1, pp. 436-46. IUCN Publication no. 24. Morges, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.

* Cowan, I. McT. (1946) "Antlered Doe Mule Deer." Canadian Field-Naturalist 60: 11-12.

* Crispens, C. G., Jr., and J. K. Doutt (1973) "Sex Chromatin in Antlered Female Deer." Journal of Wildlife Management 37:422-23.

* Donaldson, J. C., and J. K. Doutt (1965) "Antlers in Female White-tailed Deer: A 4-Year Study." Journal of Wildlife Management 29:699-705.

* Doutt, J. K., and J. C. Donaldson (1959) "An Antlered Doe With Possible Masculinizing Tumor." Journal of Mammalogy 40:230-36.

* Geist, V. (1981) "Behavior: Adaptive Strategies in Mule Deer." In O. C. Wallmo, ed., Mule and Black-tailed Deer of North America, pp. 157-223. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press.

* Halford, D. K., W. J. Arthur III, and A. W. Alldredge (1987) "Observations of Captive Rocky Mountain Mule Deer Behavior." Great Basin Naturalist 47:105-9.

* Hesselton, W. T., and R. M. Hesselton (1982) "White-tailed Deer." In J. A. Chapman and G. A. Feldhamer, eds., Wild Mammals of North America: Biology, Management, and Economics, pp. 878-901. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press.

* Hirth, D. H. (1977) "Social Behavior of White-Tailed Deer in Relation to Habitat." Wildlife Monographs 53:1-55.

Jacobson, H. A. (1994) "Reproduction." In D. Gerlach, S. Atwater, and J. Schnell, eds., Deer, pp. 98-108. Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books.

Marchinton, R. L., and D. H. Hirth (1984) "Behavior." in L. K. Halls, ed., White-tailed Deer: Ecology and Management, pp. 129-68. Harrisburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books; Washington, DC: Wildlife Management Institute.

Marchinton, R. L. and W. G. Moore (1971) "Auto-erotic Behavior in Male White-tailed Deer." Journal of Mammalogy 52:616-17.

* Rue, L. L., III (1989) The Deer of North America. 2nd ed. Danbury, Conn.: Outdoor Life Books.

Sadleir, R. M. F. S. (1987) "Reproduction of Female Cervids." In C. M. Wemer, ed., Biology and Management of the Cervidae, pp. 123-44. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Salwasser, H., S. A. Holl, and G. A. Ashcraft (1978) "Fawn Production and Survivial in the North Kings River Deer Herd." California Fish and Game 64:38-52.

* Taylor, D. O. N., J. W. Thomas, and R. G. Marburger (1964) "Abnormal Antler Growth Associated with Hypogonadism in White-tailed Deer of Texas." American Journal of Veterinary Research 25:179-85.

* Thomas, J. W., R. M. Robinson, and R. G. Marburger (1970) Studies in Hypogonadism in White-tailed Deer of the Central Mineral Region of Texas. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Technical Series no. 5. Austin: Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

* --- (1965) "Social Behavior in a White-tailed Deer Herd Containing Hypogonadal Males." Journal of Mammalogy 46:314-27.

* --- (1964) "Hypogonadism in White-tailed Deer in the Central Mineral Region of Texas." In J. B. Trefethen, ed., Transactions of the North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conference 29:225-36. Washington, D.C.: Wildlife Management Institute.

* Wishart, W. D. (1985) "Frequency of Antlered White-tailed Does in Camp Wainright, Alberta." Journal of Mammalogy 35:486-88.

* Wislocki, G. B. (1956) "Further Notes on Antlers in Female Deer of the Genus Odocoileus." Journal of Mammalogy 37:231-35.

* --- (1954) "Antlers in Female Deer, With a Report on Three Cases in Odocoileus." Journal of Mammalogy 35:486-95.

* Wong, B., and K. L. Parker (1988)"Estrus in Black-tailed Deer." Journal of Mammalogy 69:168-71.

{383}

Deer

Deer

WAPITI, ELK, or RED DEER (Cervus elaphus)

IDENTIFICATION: A large deer (standing 4-5 feet at the shoulder) with brownish red fur and a pale rump patch; males generally have enormous antlers and a long mane. DISTRIBUTION: Southern Canada, United States, northern Mexico; Eurasia, northwest Africa. HABITAT: Varied, including forests, meadows, chaparral, highlands. STUDY AREAS: Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park, California, subspecies C.e. roosevelti, the Roosevelt Elk; Isle of Rhum, Scotland, subspecies C.e. scoticus, the British Red Deer.

BARASINGHA or SWAMP DEER (Cervus duvauceli)

IDENTIFICATION: A 3-4-foot-tall deer with a brownish coat and large antlers (3 feet long) in males. DISTRIBUTION: India, Nepal; vulnerable. HABITAT: Meadows, woodland, marshy grassland. STUDY AREA: Kanha National Park, Madhya Pradesh, India; subspecies C.d. brannderi, the South Indian Barasingha.

Social Organization

Male Wapiti/Red Deer live for nine to ten months of the year in bachelor groups, while females (cows or hinds) associate with each other and their offspring in matriarchal groups. During the rut, which lasts for one to two months, males herd females and mate polygamously with them. Barasingha generally live in groups of 3-13 animals, although toward the end of the rutting season aggregations of up to 70 Deer may form. During most of the year Barasingha herds are sex-segregated.

A female Red Deer mounting another female

Description

Behavioral Expression: In both of these Deer species, homosexual mounting occurs outside of the breeding season — in females among Barasingha, and in both sexes among Wapiti and Red Deer (Wapiti or Elk is the name for this species in North America, Red Deer is the European name). In addition, Red Deer hinds sometimes mount one another when they are in heat during the breeding season. Female homosexual mounting in Wapiti generally takes place in the cow groups. Usually the two animals engaging in same-sex activity are fully grown adults, but in male Wapiti homosexual mounting may occur between adult bulls and spikehorns (yearlings {384}

whose antlers are spikes, having yet to develop prongs). Red Deer yearlings also participate in same-sex activity, including occasional incestuous homosexual mountings by females of their mothers. Homosexual mounting is done in the same position as heterosexual mating, with one animal behind the other; Red Deer stags have been observed with a full erection when mounting another male. In Wapiti and female Red Deer, same-sex (and opposite-sex) mounting may also be preceded by CHIN-RESTING, in which one animal rests its chin on the rump of the other, signaling his or her intention to mount. About a third of all Red Deer females participate in homosexual mounting as both mounter and mountee, while another third only participate as mounters, and another third only as mountees. Reciprocal mounting — in which two animals take turns mounting each other — sometimes occurs in male Wapiti. A type of same-sex, "platonic" pair-bonding is also found in this species. Both males and females may form "companionships" with an animal of the same sex; female companions are usually of the same age, while male companions may be two adult bulls, or an adult male with a younger male. Occasionally bulls will try to separate female companions during the breeding season. Their bond is strong, however, and the females travel great distances to rejoin each other, calling toward their companion until they are reunited.

Among Red Deer, gender-mixing individuals with various antler configurations are occasionally found. In this species, the vast majority of males have antlers; however, some stags, known as HUMMELS, physically resemble females in that they do not have this secondary sexual characteristic. Interestingly, hummels are in many ways more successful than antlered stags. Many become "master stags," that is, the highest ranking males, because they are generally in better physical condition, more resourceful, better fighters (in spite of not having antlers), and more successful at mating with females than antlered males. In addition, a few males are PERUKES, that is, their antlers are spikes and permanently covered in velvet. Such males are generally nonreproductive, having undeveloped testes. Antlered females also sometimes occur.

Frequency: Same-sex mounting occurs occasionally among Wapiti; in Barasingha, approximately 2-3 percent of sexual activity is between females. Homosexual mounting makes up about a third of all mounting behavior outside the {385}

breeding season in Red Deer, with the majority of this activity (64 percent) taking place between females.

Orientation: In Red Deer, about 70 percent of all females engage in some homosexual activity outside the rutting season; of these, about 30 percent participate exclusively in homosexuality, while the remainder are bisexual. The proportion of homosexual activity in bisexual females ranges from 6 percent to 80 percent, with the average being about 48 percent same-sex mounting per individual. Life histories of individual Wapiti and Barasingha that participate in homosexual mounts have not been compiled, so it is not known whether they also engage in heterosexual behavior.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Significant portions of the Wapiti and Red Deer population do not participate in reproduction. Only about a third of adult male Wapiti and half of adult male Red Deer mate with females each year. In fact, some Red Deer males (and a few females) are lifetime nonbreeders, never fathering offspring; others may have a postreproductive period in their old age. Moreover, about 30 percent of females, on average, are nonreproductive each season; individuals that do not breed generally have a lower mortality rate than breeders. As described above, Deer society is largely sex-segregated: males and females live mostly separate from each other except for one month out of the year (during the breeding season). Nevertheless, some heterosexual activity does take place outside of the rutting season: younger male Wapiti — often those that did not breed the previous season — may try to court and mount females, and heterosexual mounting also occurs outside the rut in Red Deer. Interestingly, some female Wapiti come into heat outside of the breeding season, but they are usually ignored by most adult males.

Even during the breeding season, heterosexual relations are sometimes strained: female Wapiti often refuse to be mounted by adult males, and they bite or kick yearling males that try to mate with them. On the other hand, a variety of nonprocreative sexual behaviors also make up the heterosexual repertoire: male Wapiti and Red Deer may lick and nuzzle the female's genitals, while REVERSE mounts (in which the female mounts the male) make up more than a quarter of all heterosexual activity outside the breeding season in Red Deer (they also occur in Wapiti). Both Red Deer and Wapiti males also masturbate, using a fairly unusual method: antlers in these species are actually erotic zones, and males derive sexual stimulation by rubbing them against vegetation. Red Deer stags have regularly been observed developing an erection and ejaculating from this activity. Sexual behavior by calves — including adult-calf interactions — also occurs in these species. Wapiti/Red Deer calves sometimes mount adults (including their mothers, in Red Deer), while female Red Deer occasionally mount calves. More than half of all mounting by yearling Red Deer is incestuous, with the younger animal mounting its mother. Finally, Wapiti females have developed a communal parenting or "day-care" system of CALF POOLS or

CRÈCHES. These nursery groups, containing up to 50 or more calves, {386}

form in late summer to early fall, with one or two females watching over the youngsters while the other mothers go off on their own.

Other Species

In Pere David's Deer (Elaphurus davidianus) stags sometimes mount each other, with younger males typically mounting older ones. Male Reeve's Muntjacs (Muntiacus reevesi), a small Chinese Deer, sometimes court other males. Transgendered peruke stags occasionally occur in other species such as Sika Deer (Cervus nippon) — where they may have a female coat color — Roe Deer (Capreolus capreolus), and Fallow Deer (Dama dama). In addition, intersexual individuals combining the genitals or reproductive organs of both sexes also occur in these species, as do Indian Muntjacs (Muntiacus muntjak) with a combined male-female chromosomal pattern (XXY).

Sources (* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

Altmann, M. (1952) "Social Behavior of Elk, Cervus canadensis nelsoni, in Jackson Hole Area of Wyoming." Behavior 4:116-43.

* Barrette, C. (1977) "The Social Behavior of Captive Muntjacs Muntiacus reevesi (Ogilby 1839)." Zeitschrift fur Tierpsychologie 43:188-213.

* Chapman, D. I., N. G. Chapman, M. T. Horwood, and E. H. Masters (1984) "Observations on Hypogonadism in a Perruque Sika Deer (Cervus nippon)." Journal of Zoology, London 204:579-84.

Clutton-Brock, T. H., F. E. Guiness, and S. D. Albon (1983) "The Costs of Reproduction to Red Deer Hinds." Journal of Animal Ecology 52:367-83.

--- (1982) Red Deer: Behavior and Ecology of Two Sexes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

* Darling, E. E. (1937) A Herd of Red Deer. London: Oxford University Press.

* Donaldson, J. C., and J. K. Doutt (1965) "Antlers in Female White-tailed Deer: A 4-Year Study." Journal of Wildlife Management 29:699-705.

Franklin, W. L., and J. W. Lieb (1979) "The Social Organization of a Sedentary Population of North American Elk: A Model for Understanding Other Populations." In M. S. Boyce and L. D. Hayden-Wing, eds., North American Elk: Ecology, Behavior, and Management, pp. 185-98. Laramie: University of Wyoming.

Graf, W. (1955) The Roosevelt Elk. Port Angeles, Wash.: Port Angeles Evening News.

* Guiness, E., G. A. Lincoln, and R.V. Short (1971) "The Reproductive Cycle of the Female Red Deer, Cervus elaphus L." Journal of Reproduction and Fertility 27:427-38.

* Hall, M. J. (1983) "Social Organization in an Enclosed Group of Red Deer (Cervus elaphus L.) on Rhum. II. Social Grooming, Mounting Behavior, Spatial Organization, and Their Relationships to Dominance Rank." Zeitschrift fur Tierpsychologie 61:273-92.

* Harper, J. A., J. H. Harn, W. W. Bentley, and C. F. Yocom (1967) "The Status and Ecology of the Roosevelt Elk in California." Wildlife Monographs 16: 1-49.

* Lieb, J. W. (1973) "Social Behavior in Roosevelt Elk Cow Groups." Master's thesis, Humboldt State University.

* Lincoln, G. A., R. W. Youngson, and R. V. Short (1970) "The Social and Sexual Behavior of the Red Deer Stag." Journal of Reproduction and Fertility suppl. 11:71-103.

Martin, C. (1977) "Status and Ecology of the Barasingha (Cervus duvauceli branderi) in Kanha National Park (India)." Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 74:60-132.

Morrison, J. A. (1960) "Characteristics of Estrus in Captive Elk." Behavior 16:84-92.

Prothero, W. L., J. J. Spillett, and D. E. Balph (1979) "Rutting Behavior of Yearling and Mature Bull Elk: Some Implications for Open Bull Hunting." In M. S. Boyce and L. D. Hayden-Wing eds., North American Elk: Ecology, Behavior, and Management, pp. 160-65. Laramie: University of Wyoming.

* Schaller, G. B. (1967) The Deer and the Tiger. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

* Schaller, G. B., and A. Hamer (1978) "Rutting Behavior of Pere David's Deer, Elaphurus davidianus." Zoologische Garten 48:1-15.

* Wurster-Hill, D. H., K. Benirschke, and D. I. Chapman (1983) "Abnormalities of the X Chromosome in Mammals." In A. A. Sandberg, ed., Cytogenetics of the Mammalian X Chromosome, Part B, pp. 283-300. New York: Alan R. Liss.

{387}

Deer

Deer

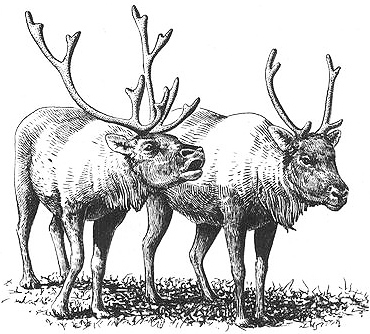

CARIBOU or REINDEER (Rangifer tarandus)

IDENTIFICATION: A medium-sized deer typically with a grayish brown coat and white underparts, and antlers in both sexes. DISTRIBUTION: Circumboreal, induding northern North America and Eurasia. HABITAT: Tundra, taiga, coniferous forest. STUDY AREA: Badger, Newfoundland, Canada; subspecies R.t caribou, the Woodland Caribou, and R.t. groenlandicus, the Barren-Ground Caribou.

MOOSE (Alces alces)

IDENTIFICATION: The largest species of deer (weighing up to 1,300 pounds); has slender legs, a pendulous nose, and (in males) prominent palmate antlers and a dewlap or "bell" beneath the throat. DISTRIBUTION: Northern Eurasia and North America. HABITAT: Moist woodland. STUDY AREAS: Jackson Hole, Wyoming; Kenai Peninsula, Alaska; Badger, Newfoundland; Wells Gray Provincial Park, British Columbia, Canada; subspecies A.a. shirasi, the Wyoming Moose; A.a. gigas, A.a. ameacana, and

A.a. andersoni.

Social Organization

Caribou are highly gregarious, sometimes forming herds of tens or even hundreds of thousands of animals (although most groups contain 40-400 animals). They typically associate in all-male, mother-calf, and juvenile/adolescent bands. Moose, on the other hand, are more solitary, although they form aggregations of up to several dozen animals during the fall rutting period. Groups of bulls and cosexual herds may also coalesce after the mating season. In both species, animals mate with multiple partners rather than forming long-term heterosexual bonds, and males do not participate in raising their young (i.e., they have a polygamous mating system).

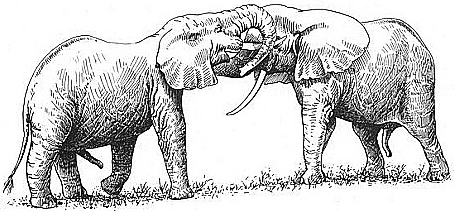

A male Caribou (left) courting another male by "vacuum licking"

Description

Behavioral Expression: Caribou and Moose occasionally participate in a variety of same-sex courtship and sexual activities. Male Moose, for example, sometimes direct courtship behaviors toward other males, including sniffing the anal and genital region, and approaching another bull while making the characteristic rutting sound, the CROAK (a grunting call that combines a deep, resonant syllable with a popping or suction noise). Younger male Caribou may also court other {388}

males by making a similar sound, sometimes known as SLURPING or VACUUM LICKING, in which the animal flicks or smacks his tongue against the upper palate while approaching the other male with his head outstretched. Female Caribou sometimes mount each other, as do younger males, while yearling male Moose have been observed trying to mount adult bulls. In addition, bull Moose sometimes associate with younger male companions — known as SATELLITES — that travel together in pairs or small groups, usually outside the breeding season. Another homosexual activity among males in both Moose and Caribou is antler rubbing. In these two species (as in several other types of Deer), antlers are highly sensitive organs and genuine erotic zones, and males may become sexually aroused when they rub their antlers together. Among Moose, this is done rather gently as a sort of "play-fighting" (the antlers may still have their velvet covering), while Caribou males rattle their antlers against each other when they are free of velvet.

Several types of gender-mixing occasionally occur in Moose, often involving unusual antler configurations. Intersexed males lacking a scrotum or testes sometimes develop what are known as VELERICORN antlers, which are covered in velvet and festooned with various ridges and knobs; such antlers are permanent, unlike regular antlers, which are shed and regrown each season. Other males — sometimes known as PERUKES — have elaborate, misshapen antlers covered with baroque nodule-like growths. Occasionally, females develop antlers, which may be single; spiked (without branches); covered in velvet; or lacking the flat, palmated structure typical of male Moose antlers. Caribou are the only deer in which females regularly sport antlers: depending on the population, anywhere from 8-95 percent of females may be antlered.

Frequency: Homosexual activity occurs only sporadically in Moose and Caribou. About a quarter of all male Moose associate together in pairs during at least part of the year.

Orientation: Adult animals that participate in homosexual activities in these two species are, in all likelihood, predominantly heterosexual, albeit with some {389}

bisexual capability. Some younger animals — especially among male Moose — may tend toward a less heterosexually oriented bisexuality, since many do not fully participate in heterosexual mating.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

In both Moose and Caribou, many animals do not procreate. Caribou males are physiologically capable of breeding when they are a year old, yet most do not mate until they are at least four years old since they cannot successfully compete with the older bucks; a similar pattern is found in Moose. Among Caribou, females without calves may associate with a breeding female as an "assistant mother," and some even try to "kidnap" or lure a calf away from its biological mother. During severe food shortages, pregnant Caribou females may terminate the breeding process by reabsorbing their embryos, since they would not be able to successfully raise their calves under such conditions. Approximately 8 percent of the male Caribou population consists of older (10+ years), postreproductive males that do not participate in breeding. However, many stags never reach this age, since the life expectancy of males is considerably shorter than that of females, at least in part because of the stresses associated with breeding. In Moose, breeding is also a taxing activity for bulls, who fast completely during the rutting period. Mating can also be a traumatic activity for females: because males in these two species are considerably larger, females often suffer injuries from copulation, sometimes literally collapsing under the weight of a male mounting them. As a result, female Caribou often strongly resist mating attempts and struggle to escape (less than two-thirds of matings are completed), while males may strike them with their antlers to make them submit to mounting. Females, in turn, may use their own antlers to fight back. Female Moose often strike males with their front hooves during the rutting season as well, and are capable of inflicting serious injury. In both species, there is significant segregation of the sexes outside of the breeding season: in Moose, for example, only 10-20 percent of winter groups are cosexual.

Moose and Caribou also participate in a variety of nonreproductive sexual behaviors. Males of both species sometimes try to mount calves, and female Caribou sometimes REVERSE mount males. Heterosexual interactions often involve oral-genital contact — male Moose and Caribou lick the female's vulva, while female Caribou sometimes lick the male's penis. About 45 percent of heterosexual mounts in Moose do not involve penetration or ejaculation, and males sometimes mount females up to 14 times in a sequence. In addition, both male Moose and Caribou "masturbate" by rubbing their antlers against vegetation, which often results in sexual stimulation (including erection of the penis and possibly ejaculation).

Sources (* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

Altmann, M. (1959) "Group Dynamics in Wyoming Moose During the Rutting Season." Journal of Mammalogy 40:420-24.

* Bergerud, A. T. (1974) "Rutting Behavior of Newfoundland Caribou." In V. Geist and F. Walther, eds., The Behavior of Ungulates and Its Relation to Management, vol. 1, pp. 395-435. IUCN Publication no. 24. Morges, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. {390}

* Bubenik, A. B., G. A. Bubenik, and D. G. Larsen (1990) "Velericorn Antlers on a Mature Male Moose (Alces a. gigas)." Alces 26:115-28.

Bubenik, A. B., and H. R. Timmerman (1982) "Spermatogenesis of the Taiga-Moose — a Pilot Study." Alces 18:54-93.

* Denniston, R. H., II (1956) "Ecology, Behavior, and Population Dynamics of the Wyoming or Rocky Mountain Moose, Alces alces shirasi." Zoologica 41: 105-18.

de Vos, A. (1958) "Summer Observations on Moose Behavior in Ontario." Journal of Mammalogy 39:128-39.

* Dodds, D. G. (1958) "Observations of Pre-Rutting Behavior in Newfoundland Moose." Journal of Mammalogy 39:412-16.

* Geist, V (1963) "On the Behavior of the North American Moose (Alces alces andersoni Peterson 1950), in British Columbia." Behavior 20:377-416.

Houston, D. B. (1974) "Aspects of the Social Organization of Moose." In V. Geist and F. Walther, eds., The Behavior of Ungulates and Its Relation to Management, vol. 2, pp. 690-96. IUCN Publication no. 24. Morges, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.

Kojola, I. (1991) "Influence of Age on the Reproductive Effort of Male Reindeer." Journal of Mammalogy 72:208-10.

* Lent, P. C. (1974) "A Review of Rutting Behavior in Moose." Naturaliste canadien 101:307-23.

--- (1966) "Calving and Related Social Behavior in the Barren-Ground Caribou." Zeitschrift fur Tierpsychologie 23:701-56.

Miquelle, D. G., J. M. Peek, and V. Van Ballenberghe (1992) "Sexual Segregation in Alaskan Moose." Widlife Monographs 122:1-57.

* Murie, O. J. (1928) "Abnormal Growth of Moose Antlers." Journal of Mammalogy 9:65.

* Pruitt, W. O., Jr. (1966) "The Function of the Brow-Tine in Caribou Antlers." Arctic 19:111-13.

--- (1960) "Behavior of the Barren-Ground Caribou." Biological Papers of the University of Alaska 3:1-44.

* Reimers, E. (1993) "Antlerless Females Among Reindeer and Caribou." Canadian Journal of Zoology 71:1319-25.

Skogland, T. (1989) Comparative Social Organization of Wild Reindeer in Relation to Food, Mates, and Predator Avoidance. Advances in Ethology no. 29. Berlin and Hamburg: Paul Parey Scientific Publishers.

Van Ballenberghe, V, and D. G. Miquelle (1993) "Mating in Moose: Timing, Behavior, and Male Access Patterns." Canadian Journal of Zoology 71:1687-90.

* Wishart, W. D. (1990) "Velvet-Antlered Female Moose (Alces alces)." Alces 26:64-65.

{391}

GIRAFFES, ANTELOPES, AND GAZELLES

Giraffes and Antelopes

Giraffes and Antelopes

GIRAFFE (Giraffa camelopardalis)

IDENTIFICATION: The tallest mammal (up to 19 feet), with a sloping back, enormously long neck, bony, knobbed "horns" in both sexes, and the familiar reddish brown spotted patterning. DISTAIBUTION: Sub-Saharan Africa. HABITAT: Savanna. STUDY AREAS: Tsavo East and Nairobi National Parks, Kenya; Serengeti, Arusha, and Tarangire National Parks, Tanzania; eastern Transvaal, South Africa; subspecies G.c. tippel-skirchi, the Masai Giraffe, and

G.c. giralla.

Social Organization

Female Giraffes tend to congregate in groups of up to 15 individuals, including their calves and perhaps a few younger males. Males generally associate in all-male "bachelor" groups, but tend to become solitary as they get older. The mating system is polygamous: mostly a few older males mate with more than one female, but take no part in raising their offspring.

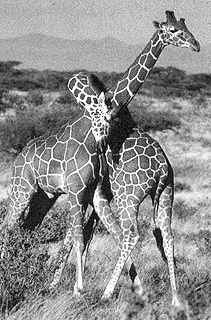

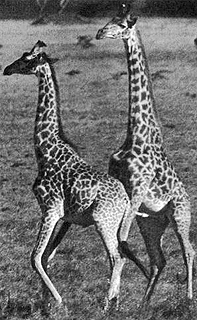

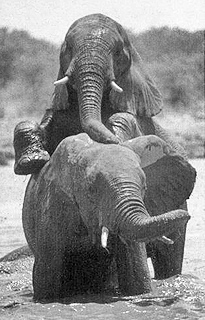

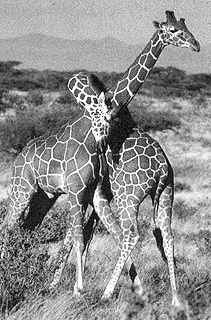

Two male Giraffes engaging in "necking" behavior

Description

Behavioral Expression: Male Giraffes have a unique "courtship" or affectionate activity called NECKING, which is often associated with homosexual mounting. When necking, two males stand side by side, usually facing in opposite directions, while they gently rub their necks on each other's body, head, neck, loins, and thighs, sometimes for as long as an hour. Necking sessions are usually initiated with one male assuming a formal posture with his neck held rigid and upright. One male {392}

may also affectionately lick the other's back or sniff his genitals during necking. Necking Giraffes also sometimes swing their necks at each other in what has been described as a "stately dance" or a form of play-fighting (although they rarely hit, and virtually never injure, each other). Necking usually leads to sexual arousal: one or both males develop erections, and occasionally one might exhibit a curling of the lip similar to the FLEHMEN response seen in heterosexual courtships (associated with sexual arousal and testing sexual "readiness"). Sometimes after necking for 15 minutes or so, one male suddenly stops and "freezes" with his neck stretched forward, which is thought to indicate intense sexual excitement approaching orgasm. Males also commonly mount each other with erect penises during or following bouts of necking and probably reach orgasm (sometimes liquid — presumably semen — can be seen streaming from their penises). At times, groups of four or five males will gather to neck and mount each other, and males may mount several individuals in quick succession or the same male as many as three times in a row. Females also occasionally mount each other, but they do not participate in necking.

A male Giraffe mounting another male

Frequency: Homosexual activity is common in Giraffes and in many cases is actually more frequent than heterosexual behavior (which may be quite rare): in one study area, mountings between males accounted for 94 percent of all observed sexual activity. Anywhere from a third to three-quarters of all courtship sessions are homosexual (i.e. they involve necking between males), and at any given time, about 5 percent of all males are participating in necking. Among females, less than 1 percent of interactions involving body contact consist of homosexual mounting.

Orientation: Homosexual activity is characteristic of younger adult males, who may constitute more than 80 percent of the male population. As they get older, males participate less in homosexual courtship and mounting and more in heterosexual activity. Among younger males, it is likely that all of their mounting behavior is homosexual, although a small percentage also court (but do not {393}

mount) females. Males participating in homosexual mounting and necking frequently disregard any females present in the herd, perhaps indicating a "preference" for same-sex activity.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Only a relatively small percentage of adult Giraffes breed: in some populations, less than a quarter of the females reproduce in any year, while usually only one or two males actually mate with females. A number of factors contribute to this infrequency of breeding: pregnancies last 15 months, and there is a minimum of 20 months between calves. Males are unable to compete successfully for matings until they are at least eight years old, even though they mature sexually at under four years. And as mentioned above, actual copulations can be remarkably rare — in one population, only a single heterosexual mating was observed during more than 3,200 hours of detailed observation over an entire year. In some areas, it also appears that a small class of old, postreproductive males are generally solitary and do not court or mate with females. Giraffes engage in a few forms of nonprocreative heterosexual activity as well: younger females in heat occasionally mount male calves, while calves sometimes mount their mothers. As in most polygamous animals, males do not participate in calf-raising. Females, however, often leave their young in nursery groups or CALVING POOLS containing as many as nine other calves, attended by one or more of the other mothers. This "day-care" arrangement allows a female to feed on her own without having to constantly look after her calf.

Sources (* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

* Coe, M. J. (1967) "'Necking' Behavior in the Giraffe." Journal of Zoology, London 151:313-21.

* Dagg, A. I., and J. B. Foster (1976) The Giraffe: Its Biology, Behavior, and Ecology. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

* Innis, A. C. (1958) "The Behavior of the Giraffe, Giraffa camelopardalis, in the Eastern Transvaal." Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 131:245-78.

Langman, V. A. (1977) "Cow-Calf Relationships in Giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis giraffa)." Zeitschrift fur Tierpsychologie 43:264-86.

* Leuthold, B. M. (1979) "Social Organization and Behavior of Giraffe in Tsavo East National Park." African Journal of Ecology 17:19-34.

* Pratt, D. M., and V. H. Anderson (1985) "Giraffe Social Behavior." Journal of Natural History 19:771-81.

--- (1982) "Population, Distribution, and Behavior of Giraffe in the Arusha National Park, Tanzania." Journal of Natural History 16:481-89.

--- (1979) "Giraffe Cow-Calf Relationships and Social Development of the Calf in the Serengeti." Zeitschrift fur Tierpsychologie 51:233-51.

* Spinage, C. A. (1968) The Book of the Giraffe. London: Collins.

{394}

Giraffes and Antelopes

Giraffes and Antelopes

PRONGHORN (Antilocapra americana)

IDENTIFICATION: A deer-sized mammal with distinctive, sharply forked horns in males and reddish brown fur with white patches. DISTRIBUTION: West-central United States, adjacent areas of Canada and Mexico. HABITAT: Prairies, deserts. STUDY AREAS: Yellowstone National Park and National Bison Range, Montana; subspecies A.a. americana.

Social Organization

Pronghorn society is characterized by a distinction between territorial males, who establish territories and mate with females, and nonterritorial males, who live primarily in bachelor herds of seven to ten individuals throughout the spring and into early fall. Females associate in groups of up to two dozen individuals, often accompanied by a territorial male. After the breeding season — during which males copulate with multiple partners and do not assist in parenting — most Pronghorns join large mixed-sex herds for the winter.

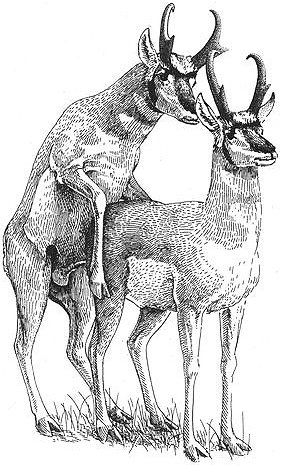

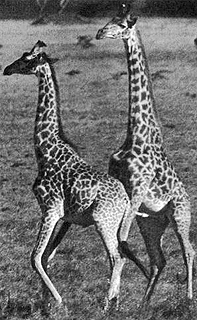

A male Pronghorn mounting another male

Description

Behavioral Expression: Male Pronghorns court and mount each other in their bachelor herds from April to October, using many of the same behavior patterns found in heterosexual courtship and mating. As a prelude to sexual behavior, one male follows another, sometimes sniffing his anal region. The courting male might then touch his chest to the other male's rump, a signal that he wants to mount. Usually this leads to a full mount, in which the courting male rises on his hind legs and, with erect penis, slides up onto the other male from behind. Sometimes a whole string or "chain" of courting males forms as each follows and tries to mount the male in front of him. Males of all age groups participate in homosexual courtship and mounting, although adult males usually direct their attentions to adolescent males. Mounting between males sometimes occurs during sparring or play-fighting as well. Female Pronghorns also rump-sniff and mount each other {395}

when they are in heat, though less frequently than males.

Male Pronghorns shed their horns after the breeding season and some researchers have suggested that this allows them to "pass" as females in mixed-sex herds during the winter. Since males are usually physically exhausted after the rut, they make easier targets for predators than females: by engaging in a form of female mimicry or transvestism, they may avoid being singled out.

Frequency: Overall, about 7 percent of all courtship/sexual behavior is between animals of the same sex, and about 10 percent of all mounts are homosexual (roughly two-thirds of these are between males). Among animals of the same sex, approximately 3-4 percent of their interactions involve some sort of sexual behavior.

Orientation: Anywhere from two-thirds to three-quarters of the male population does not participate in breeding; many of these animals are exclusively homosexual. Two-year-old males, for example, never mount females, yet bachelors participate in nearly a third of all homosexual mounts. At the other end of the scale, territorial males are exclusively heterosexual. In between, various forms of bisexuality occur. About 7 percent of adult bachelor males are able to mate with females, yet they also account for 18 percent of homosexual interactions. Some males transfer from the bachelor herds to territorial status, thereby participating in sequential bisexuality over the course of their lives. Many males, however, never become territorial, and though they may try to court females, most of their sexual behavior will continue to be homosexual for the majority — if not the totality — of their lives.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

As described above, the majority of the male population is not involved in procreation, living as they do in bachelor herds or as loners, and Pronghorn social life is characterized by sex segregation for six to seven months of the year. Some bachelors, however, do try to court females; although their advances are consistently {396}

rebuffed, the males often persist and may harass the females relentlessly by chasing them, horning and roaring at them, and sometimes even knocking them down during a chase. Reproduction in the Pronghorn is also characterized by aggression within the womb: procreation routinely involves embryos killing each other. As many as seven embryos may initially be present in the female's uterus, but only two of these will survive. The remainder are killed by the other developing fetuses, which grow long projections out of their fetal membranes that fatally puncture the others and drag them out of the uterus back up into the female's oviduct. Some embryos also die earlier because they get strangled in the ropelike bodies of the other embryos. The female reabsorbs any embryos that die.

Sources (* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

Bromley, P. T. (1991) "Manifestations of Social Dominance in Pronghorn Bucks." Applied Animal Behavior Science 29:147-64.

Bromley, P. T., and D. W. Kitchen (1974) "Courtship in the Pronghorn Antilocapra americana." In V. Geist and F. Walther, eds., The Behavior of Ungulates and Its Relation to Management, vol. 1, pp. 356-74. IUCN Publication no. 24. Morges, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.

Geist, V. (1990) "Pronghorns." In Grzimek's Encyclopedia of Mammals, vol. 5, pp. 282-85. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Geist, V., and P. T. Bromley (1978) "Why Deer Shed Antlers." Zeitschrift fur Saugetierkunde 43:223-31.

* Gilbert, B. K. (1973) "Scent Marking and Territoriality in Pronghorn (Antilocapra americana) in Yellowstone National Park." Mammalia 37:25-33.

* Kitchen, D. W. (1974) "Social Behavior and Ecology of the Pronghorn." Wildlife Monographs 38:1-96.

O'Gara, B. W. (1978) "Antilocapra americana." Mammalian Species 90:1-7.

--- (1969) "Unique Aspects of Reproduction in the Female Pronghorn (Antilocapra americana Ord.)" American Journal of Anatomy 125:217-32.

{397}

Kob Antelopes

Kob Antelopes

KOB (Kobus kob)

IDENTIFICATION: A large grazing antelope with a reddish coat, white underparts, and black markings on the legs; males have lyre-shaped horns, while females are more slender. DISTRIBUTION: Western Kenya to Senegal. HABITAT: Open savanna near water. STUDY AREA: Toro Game Reserve, Uganda; subspecies K.k. thomasi, the Uganda Kob.

WATERBUCK (Kobus ellipsiprimnus)

IDENTIFICATION: A 4-foot-tall (shoulder height) antelope with long, straggly brown or grayish hair and a white rump; males have sickle-shaped, ridged horns. DISTRIBUTION: Sub-Saharan Africa. HABITAT: Grassland, savanna, forest near water. STUDY AREA: Queen Elizabeth Park, Uganda; subspecies K.e. defassa, the Defassa Waterbuck.

LECHWE (Kobus leche)

IDENTIFICATION: Similar to Kob, but horns longer and thinner, and coat yellowish brown to black. DISTRIBUTION: Southeastern Zaire, Zambia, Botswana. HABITAT: Wetlands. STUDY AREAS: Chobe Game Reserve and Lochinvar National Park, Zambia; subspecies K.l. kafuensis, the Kafue Lechwe.

PUKU (Kobus vardoni)

IDENTIFICATION: Similar to Kob but with shorter horns. DISTRIBUTION: Scattered locations throughout south-central Africa. HABITAT: Moist savanna, floodplains, woodland. STUDY AREAS: Kafue National Park and Luangwa Game Reserve, Zambia.

Social Organization

Kob society is complex and is organized around two types of social systems: sex-segregated herds and LEKS. Outside of the breeding grounds, the antelopes congregate in same-sex herds: bachelor herds contain 400-600 males, while female herds usually have 30-50 adults (as well as young of both sexes), though they can contain as many as 1,000 antelopes. On the breeding grounds, the population is structured into a dozen or more small territories known as leks. These are small {398}

arenas that the males — and occasionally females — use for performing intricate courtship displays, and which they defend against the intrusion of other males. Females leave their herds to visit these leks, where they choose males to mate with and also interact sexually with other females. The other Kob antelopes also live in sex-segregated female and bachelor herds, although some Lechwe herds are cosexual. In addition, a few males — who do the most mating — are territorial, while some Waterbuck males are SATELLITES, associating with territorial males and occasionally mating with females.

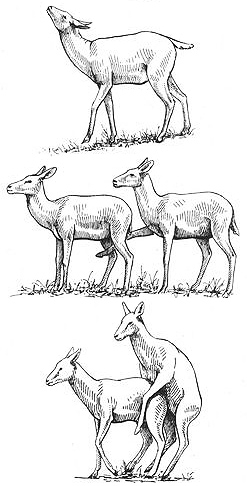

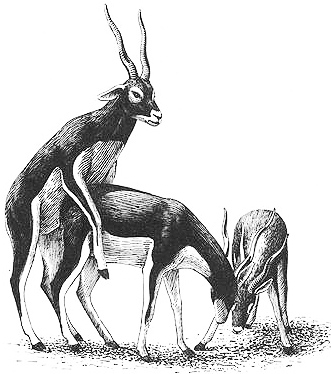

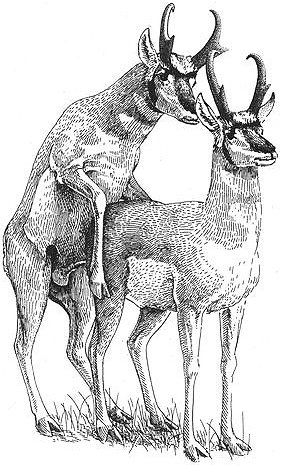

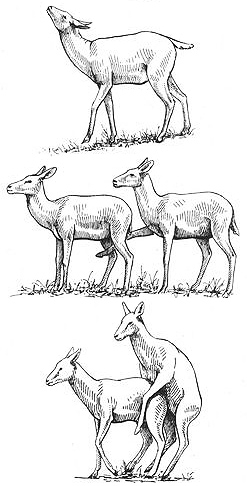

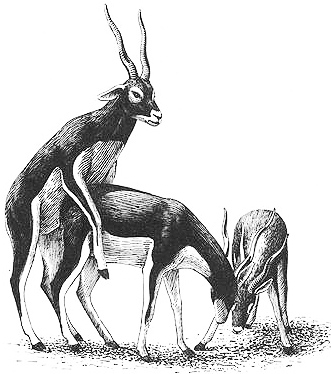

Courtship and sexual activity between female Kob: "prancing" (above), "foreleg kicking" (middle), and mounting

Description

Behavioral Expression: Virtually all Kob females engage in some form of homosexual activity, ranging from simple sexual mounting of other females all the way up to elaborate courtship displays. These interactions usually take place when the females are in heat and may occur either in the female herds or on the leks. Homosexual courtship and sexual interactions consist of a rich array of stylized movements in a fixed sequence, which are all used in heterosexual courtship as well. Individual females vary in how many of these display behaviors they employ when courting another female — some use only one or two, while others employ the full repertoire. A female usually begins her homosexual courtship by PRANCING: she approaches another female with short, stiff-legged steps, her head held high and tail raised. This is followed by an action known as FLEHMEN or LIP-CURLING: she sniffs the vulva of the other female, who crouches and urinates while her partner places her nose in the stream of urine. While doing this, she retracts her upper lip in a curling gesture, exposing a special sexual scenting organ that allows her to sample the odor of the urine. Her courtship dance continues with a stylized gesture known as FORELEG KICKING: she raises her foreleg and gently touches the other female between her legs from behind. The other female responds with ritual MATING-CIRCLING, in which she circles tightly around the courting female, sometimes nipping or butting her hindquarters. This leads to mounting, in which the first female stands on her hind legs and climbs on top of the other from behind, as in heterosexual {399}

mating. Sometimes the mounting female gives a single vigorous pelvic thrust, similar to the thrusting that a male makes when he reaches orgasm.

Homosexual copulation may be followed by a further display of stylized behaviors. The courting female, for example, might make a distinctive whistling sound by forcing air loudly through her nostrils with her mouth closed (also made by males in heterosexual courtship). The two females may also engage in what is known as INGUINAL NUZZLING: the female who was mounted adopts a special posture with her hind legs spread wide, tail raised, back arched, and her neck extended in a graceful swanlike position. The other Kob licks her partner's vulva and udder from behind and then concentrates on nuzzling and licking two special "inguinal glands" located in the same region, which secrete a pungent, waxy substance. Finally, the interaction concludes with what is known as the PINCERS MOVEMENT, in which one female gently holds the other in a "pincers" position with her head on the other Kob's back and her leg raised underneath her belly. Occasionally, a female Kob will herd other females and even defend her display territory against courting males by attacking the males head-on — no small feat, considering that she does not have the horns that most males use for such purposes. The majority of Kob that participate in homosexual mounting also become pregnant and raise young — and in all cases, this is done in the female-only herds, with little or no participation from males beyond insemination.

Female homosexual mounting also occurs in three other closely related species of antelopes, the Waterbuck, Lechwe, and Puku. Interestingly, Waterbuck females that mount each other are not usually in heat, unlike Kob. Occasionally, a Waterbuck female will perform courtship flehmen with another female as well. Hermaphrodite or intersexual individuals also sometimes occur in Kob: one animal, for example, was chromosomally male and had testes and large horns, combined with a vagina, uterus, and enlarged clitoris.

Following homosexual mounting, female Kob may engage in "inguinal nuzzling" (above) and "pincers movement" (below)

Frequency: Homosexual mounting is common among Kob. Each female participates in same-sex mounting about twice an hour (on average) during the mating season, and over an entire mating season a female might mount other females 60 or more times (although most females probably engage in this activity a dozen {400}

or so times). However, because heterosexual mounting rates are extraordinarily high — more than seven times higher than homosexual rates — same-sex mounting accounts for only about 9 percent of all sexual activity. Homosexual courtship displays are less common than same-sex mounting in this species. In Puku and Lechwe, mounting between females is also common, but it occurs only occasionally among Waterbuck.

Orientation: Most, if not all, female Kob are bisexual, participating in both heterosexual and homosexual mounting, but individuals vary along a continuum in their orientation. For some, same-sex mounting makes up nearly 60 percent of their sexual activity, while for others it constitutes only 1-3 percent, but the average is about 11 percent. Fewer Kob females use courtship displays with other females, but there is a parallel range in variation. About 7 percent of females employ a significant portion of the full courtship repertoire when interacting with other females. In the other species of Kob antelopes, females that engage in homosexual mounting probably also participate in heterosexual activities as well.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

As described above, Kob society is sex-segregated, and there are large numbers of nonbreeding animals, particularly among males. Only a relatively small proportion of males (about 5 percent) have access to lek territories at one time, and only some of these will be selected by females to mate with. In some populations of Waterbuck, large numbers of males are also nonbreeders: at any given time, only 7 percent of males are territory holders, 9 percent are satellites, and the remainder live in bachelor herds. In fact, only 20 percent of males in this species become territorial during their lives. Although a few satellite and bachelor males mate with females, the majority do not. Female Kob usually mate repeatedly with their chosen males — generally many more times than is required to become pregnant — and may copulate with up to nine different males when they visit the lek. Waterbuck females also mate repeatedly when in heat, usually with the same male each time. Kob heterosexual copulations are often preceded by numerous nonreproductive mounts in which the male does not have an erection. Furthermore, full penetration may not occur during copulation, and often the male does not ejaculate even when he does achieve penetration. Waterbuck males sometimes mount females from the side or other positions where penetration cannot occur. When all types of mounts are considered, the rate of heterosexual activity in Kob is staggering: during a 24-hour visit to the lek, each female may engage in several hundred mountings, 40 of which will be full copulations. Female Lechwe are often chased and harassed by males (especially nonterritorial ones) trying to mate with them. Sometimes several males will disrupt a heterosexual copulation, and only 8 percent of matings in cosexual herds and 42 percent on leks result in ejaculation.

Sources (* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

Balmford, A., S. Albon, and S. Blakeman (1992) "Correlates of Male Mating Success and Female Choice in a Lek-Breeding Antelope." Behavioral Ecology 3:112-23. {401}

* Benirschke, K. (1981) "Hermaphrodites, Freemartins, Mosaics, and Chimaeras in Animals." In C. R. Austin and R. G. Edwards, eds., Mechanisms of Sex Differentiation in Animals and Man, pp. 421-63. London: Academic Press.

Buechner, H. K., J. A. Morrison, and W. Leuthold (1966) "Reproduction in Uganda Kob, with Special Reference to Behavior." In I. W. Rowlands, ed., Comparative Biology of Reproduction in Mammals, pp. 71-87. Symposia of the Zoological Society of London no. 15. London: Academic Press.

Buechner, H. K., and H. D. Roth (1974) "The Lek System in Uganda Kob." American Zoologist 14:145-62.

* Beuchner, H. K., and R. Schloeth (1965) "Ceremonial Mating Behavior in Uganda Kob (Adenota kob thomasi Neumann)." Zeitschrift fur Tierpsychologie 22:209-25.

* DeVos, A., and R. J. Dowsett (1966) "The Behavior and Population Structure of Three Species of the Genus Kobus. Mammalia 30:30-55.

Leuthold, W. (1966) "Variations in Territorial Behavior of Uganda Kob Adenota kob thomasi (Neumann 1896)." Behavior 27:214-51.

Morrison, J. A., and H. K. Buechner (1971) "Reproductive Phenomena During the Post Partum-Preconception Interval in the Uganda Kob." Journal of Reproduction and Fertility 26:307-17.

Nefdt, R. J. C. (1995) "Disruptions of Matings, Harassment, and Lek-Breeding in Kafue Lechwe Antelope." Animal Behavior 49:419-29.

Rosser, A. M. (1992) "Resource Distribution, Density, and Determinants of Mate Access in Puku." Behavioral Ecology 3:13-24.

* Spinage, C. A. (1982) A Territorial Antelope: The Uganda Waterbuck. London: Academic Press.

--- (1969) "Naturalistic Observations on the Reproductive and Maternal Behavior of the Uganda Defassa Waterbuck Kobus defassa ugandae Neumann." Zeitschrift fur Tierpsychologie 26:39-47.

Wirtz, P. (1983) "Multiple Copulations in the Waterbuck (Kobus ellipsiprymnus)." Zeitschrift fur Tierpsychologie 61:78-82.

--- (1982) "Territory Holders, Satellite Males, and Bachelor Males in a High-Density Population of Waterbuck (Kobus ellipsiprymnus) and Their Associations with Conspecifics." Zeitschrift fur Tierpsychologie 58:277-300.

{402}

Gazelles

Gazelles

BLACKBUCK (Antilope cervicarpa)

IDENTIFICATION: A medium-sized gazelle; males have distinctive spiral horns and a black-and-white coat; females and juvenile males are tan colored. DISTRIBUTION: India; vulnerable. HABITAT: Semidesert to open woodland. STUDY AREAS: Kanha National Park, Madhya Pradesh, India; Cleres Park, Rouen, France.

THOMSON'S GAZELLE (Gazella thomsoni)

GRANT'S GAZELLE (Gazella granti)

IDENTIFICATION: Smaller gazelles (2-3 feet at shoulder height) with ringed, slightly S-shaped horns in both sexes; Thomson's have a conspicuous black flank band, and Grant's horns may bend sharply outward. DISTRIBUTION: East Africa, especially Kenya, Tanzania, Sudan. HABITAT: Grassy steppes. STUDY AREAS: Serengeti National Park and Ngorogoro Crater, Tanzania; subspecies G.g. robertsi, the Wide-horned Grant's Gazelle.

Social Organization

Blackbucks live in small, same-sex herds containing 10-50 individuals. Female herds circulate within the territory of one or several adult males who mate with them; the remaining males live in "bachelor" herds on the periphery of the breeding territories. Thomson's and Grant's Gazelles have a similar social organization, except that mixed herds containing both males and females also form, especially during migration.

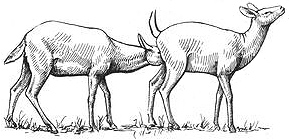

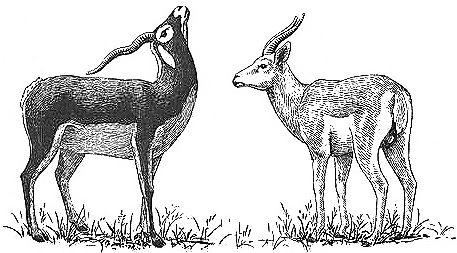

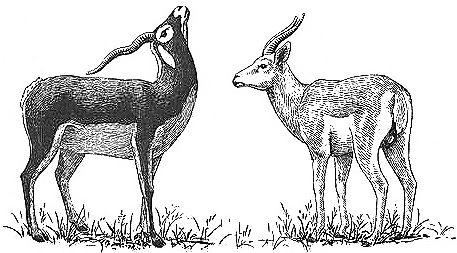

An adult male Blackbuck courting a younger male by "presenting the throat," a stylized courtship display. Some scientists have suggested that homosexual activity in this species is triggered by the resemblance between younger males and adult females (e.g., their lighter coat color), yet younger bucks are clearly identifiable as male because of their horns and other anatomical features.

Description

Behavioral Expression: The majority of male Blackbucks have homosexual interactions: among all age groups, mounting of one male by another occurs in the position used for heterosexual intercourse. Usually mounting happens during play-fighting — friendly sparring matches with erotic overtones, sometimes involving three males at a time. In addition, adult males often perform courtship displays toward adolescent males (one-to-two-year-olds) prior to mounting them. These displays, which also occur in heterosexual interactions, begin with the older male DISPLAY WALKING: he stands some distance away from the object of his attentions, lowering his ears and curling his tail up to touch his back. He walks in this posture parallel to the younger male so that the younger one has to walk in a circle. This is {403}

followed by PRESENTING THE THROAT: the older male raises his nose high in the air so that his spiral horns touch the back of his neck. This exposes the striking black-and-white pattern of his neck. While doing this, he briskly kicks first one foreleg, then the other, in front of him several times in a row, sometimes reaching under the other male's belly or between his thighs. Occasionally, the older male makes a distinctive barking sound as he does this. This is then followed by mounting of the younger male by the older. Occasionally, female Blackbucks mount other females.

In Thomson's Gazelles, male homosexual mounting may occur in a variety of contexts, including during migration and in encounters between two nonterritorial males. Males also occasionally direct courtship displays toward one another, including the NECK-STRETCH, FORELEG KICK, and NOSE-UP POSTURE, as well as the PURSUIT MARCH (the latter similar to heterosexual courtships). Homosexual courtship displays are preceded by one or both males displaying their horns to the other (often interpreted as a threatening gesture). Homosexual mounting in Grant's Gazelles typically occurs as part of a formalized display in which two males march toward one another, lifting their heads high and showing their white throat patches when they are next to each other. The mounted male, if an adult, often attacks the male trying to mount him (females also sometimes respond aggressively to a male's advances, see below).

A male Blackbuck mounting another male during a bout of play-fighting

Frequency: Male homosexual activity is common among Blackbucks: at any given time, fully three-quarters of the male population lives in the bachelor herds, where most homosexual interactions take place. Among Thomson's and Grant's Gazelles, homosexual behavior is much less frequent: 12 percent of encounters between male Grant's involve mounting, while 1-8 percent of encounters between male Thomson's involve sexual behavior.

Orientation: All Blackbuck males over three years old leave the bachelor herd temporarily to attempt mating with females. However, this usually occurs only once or twice in each male's lifetime; for the remainder of his life, he interacts homosexually. Technically, then, all male Blackbuck are bisexual, though in practice {404}

they are predominantly homosexual. In Thomson's Gazelles, homosexual mounting typically occurs among males in bachelor or migratory groups, not territorial males (who are involved principally in heterosexual activities). Although these males occasionally court and attempt to mount females, the majority of their sexual interactions may be with other males. In Grant's males, homosexual behavior does occur in some territorial males; since these males direct sexual behaviors toward both males and females, they are functionally bisexual (although males generally do not consent to being mounted by other males).

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Because of the organization of Blackbuck society into sex-segregated herds and the small number of active breeding males, only a fraction of the male population is ever involved in heterosexual activity. Furthermore, although all males attempt to leave the bachelor herds and mate with females, most are unable to do so because of the males already defending the breeding territories; consequently life in the bachelor herd is preferable for many males. Among Grant's and Thomson's Gazelles, there are similar patterns of sex segregation and nonparticipation in heterosexuality — in fact, more than 90 percent of the male Grant's population may be composed of nonbreeders at any given time. In addition, female Grant's Gazelles often behave aggressively toward males during heterosexual courtship, performing threat displays and sometimes even fighting bucks to fend off unwanted advances. Female Blackbucks sometimes engage in nonreproductive mounts of fawns or young animals.

Sources (* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

* Dubost, G., and F. Feer (1981) "The Behavior of the Male Antilope cervicapra L., Its Development According to Age and Social Rank." Behavior 76:62-127.

* Schaller, G. B. (1967) The Deer and the Tiger. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Walther, F. R. (1995) In the Country of Gazelles. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

* --- (1978a) "Quantitative and Functional Variations of Certain Behavior Patterns in Male Thomson's Gazelle of Different Social Status." Behavior 65:212-40.

* --- (1978b) "Forms of Aggression in Thomson's Gazelle; Their Situational Motivation and Their Relative Frequency in Different Sex, Age, and Social Classes." Zeitschrift fur Tierpsychologie 47:113-72.

* --- (1974) "Some Reflections on Expressive Behavior in Combats and Courtship of Certain Horned Ungulates." In V. Geist and F. Walther, eds., Behavior in Ungulates and Its Relation to Management, vol. 1, pp. 56-106. IUCN Publication no. 24. Morges, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.

--- (1972) "Social Grouping in Grant's Gazelle (Gazella granti Brooke, 1827[sic])" in the Serengeti National Park." Zeitschrift fur Tierpsychologie 31:348-403.

* --- (1965) "Verhaltensstudien an der Grantgazelle (Gazella granti Brooke, 1872) im Ngorogoro-Krater [Behavioral Studies on Grant's Gazelle in the Ngorogoro Crater]." Zeitshcrift fur Tierpsychologie 22:167-208.

{405}

WILD SHEEP, GOATS, AND BUFFALO

Mountain Sheep

Mountain Sheep

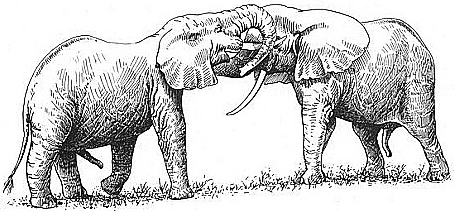

BIGHORN SHEEP (Ovis canadensis)

IDENTIFICATION: A large wild sheep (weighing up to 300 pounds) with massive spiral horns in males; coat is brown with a white muzzle, underparts, and rump patch. DISTRIBUTION: Southwestern Canada, Rocky Mountains to northern Mexico. HABITAT: Mountain and desert rocky terrain. STUDY AREAS: Banff National Park, Alberta; Kootenay National Park and the Chilcotin-Cariboo Region, British Columbia, Canada; National Bison Range, Montana; subspecies O.c. canadensis, the Rocky Mountain Bighorn, and O.c. californiana, the California Bighorn Sheep.

THINHORN SHEEP (Ovis dalli)

IDENTIFICATION: Similar to Bighorn, except smaller and with thinner horns; coat is all white or brownish black to gray, DISTRIBUTION: Alaska, northwestern Canada. HABITAT: Rocky alpine and arctic terrain. STUDY AREAS: Kluane Lake, the Yukon; Cassiar Mountains, British Columbia, Canada; subspecies O.d. dalli, Dall's Sheep, and O.d. stonei, Stone's Sheep.

ASIATIC MOUFLON (Ovis orientalis)

IDENTIFICATION: Similar to N. American wild sheep, except coat varies from reddish brown or black-brown to light tan, and males may have a light saddle patch and a "bib" or chest mane; horns can be up to 4 feet long, spiral or arching back. DISTRIBUTION: Southwest Asia (including Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan); Corsica, Sardinia, Cyprus; vulnerable. HABITAT: Hilly or steep terrain, from deserts to mountains. STUDY AREAS: Bavella, Island of Corsica, France; Salt Range near Kalabagh, Pakistan; Johnson City, Texas; subspecies O.o. musimon, the European Mouflon, and O.o. punjabiensis, the Punjab Urial.

{406}

Social Organization

Mountain Sheep live in sex-segregated bands, usually numbering 5-15 individuals. During the rutting season, the sexes intermingle and mate promiscuously (males copulate with multiple partners and do not form long-term pair-bonds or participate in parenting).

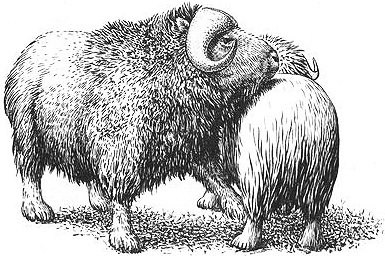

A male Bighorn Sheep in the Rocky Mountains mounting another male

Description

Behavioral Expression: In Bighorn and Thinhorn Sheep, males live in what one zoologist has described as "homosexual societies" where same-sex courtship and sexual activity occur routinely among all rams. Typically an older, higher-ranking male will court a male younger than him, using a sequence of stylized movements. Same-sex courtship is often initiated when one male approaches the other in the LOW-STRETCH posture, in which the head and neck are lowered and extended far forward. This might be combined with the TWIST, where the male sharply rotates his head and points his muzzle toward the other male, often while flicking his tongue and making growling or grumbling sounds. The courting ram often performs a FORELEG KICK, stiffly snapping his front leg up against the other male's belly or between his hind legs. He also occasionally sniffs and nuzzles the other male's genital area and may perform LIP-CURLING or FLEHMEN, in which he samples the scent of the other male's urine by retracting his upper lip to expose a special olfactory organ. Thinhorn rams may even lick the penis of the male they are courting. The male being courted sometimes rubs his forehead and cheeks on the other ram's face — even licking and nibbling him — and may also rub his horns on the other male's neck, chest, or shoulders, occasionally developing an erection. Similar courtship behaviors occur among male Asiatic Mouflons.

In addition to genital licking (in Thinhorns), sexual activity between rams usually involves mounting and anal intercourse: typically the larger male rears up on his hind legs and mounts the smaller male, placing his front legs on the other's flanks. The mountee assumes a characteristic posture known as LORDOSIS, in which he arches his back to facilitate the copulation (this posture is also seen in many female mammals during heterosexual mating). Usually the mounting male has an erect penis and achieves full anal penetration, performing pelvic thrusts that probably lead to ejaculation in many {407}

cases. Mounting and courtship interactions between males sometimes also take place in groups known as HUDDLES: three to ten rams cluster together in a circle, rubbing, nuzzling, licking, horning, and mounting each other. Usually huddles are non-aggressive interactions in which all males are willing participants; occasionally, though, several rams in a huddle focus all their attentions on the same (usually smaller) male, taking turns mounting him and even chasing him if he tries to get away. Female Mountain Sheep also occasionally participate in sexual activity with one another, including licking each other's genitals, mounting, and occasional courtship activities.

So pervasive and fundamental is same-sex courtship and sexuality in Bighorns and Thinhorns that females are said to "mimic" males in order to mate with them. They adopt the behavior patterns typical of younger males being courted by older males, thereby sparking sexual interest on the part of rams because, ironically, they now resemble males. In another twist on gender roles and sexuality, there are also occasionally "female-mimicking" males in some populations — but notably, such males do not typically participate in homosexual mounting and courtship. Transgendered males are physically indistinguishable from other rams, but behaviorally they resemble females. They remain in the sex-segregated ewe herds year-round, they often adopt the crouching urination posture typical of females, and they are lower-ranking and less aggressive than most males and even many females (even though they are often larger in body and horn size, the typical criteria used to establish rank). Most significantly, transgendered rams do not usually allow other males to court or mount them. Again, this is a typically female pattern, since ewes in these species generally do not permit rams to court or mount them except for the few days out of each year when they are in heat.

Homosexuality as a "masculine" activity: a male Bighorn ram mounts

another ram. Males who mimic females in this species (behavioral

transvestites) do not generally permit other males to mount them, unlike

nontransvestite rams.

Frequency: In Bighorns and Thinhorns, homosexual mounting occurs commonly throughout the year, but is especially frequent during the rut when heterosexual activity is also taking place, accounting for about a quarter of all sexual activity at that time (and occurring in up to 69 percent of males' interactions with each other). Outside of the rut, all mounting activity is homosexual, but mounting only accounts for 2-3 percent of males' interactions with each other. Among females, 1-2 percent of interactions include mounting. At least 70 percent of males' interactions with one another involve courtship behaviors. Homosexual activity appears to be less frequent in Asiatic Mouflons: it is seen sporadically in wild animals, while in captivity about 10 percent of mounting and some courtship behaviors occur between animals of the same sex, mostly females. Behavioral transvestism occurs in approximately 5 percent of rams in some populations of Bighorn Sheep.

Orientation: Virtually all male Bighorn and Thinhorn Sheep participate in homosexual courtship and mounting; the extent to which they also engage in heterosexual pursuits during the rut varies with their age and rank. Younger, lower-ranking rams — close to half of the male population — rarely get to mate with females at all, and some of these males have only homosexual relations. Among older, {408}

higher-ranking rams, heterosexual behavior is much more common — but even when they are courting and mounting females, it is often because of the malelike behavior patterns that the females are using (as described above). In other words, even in their heterosexuality, Mountain Sheep may be decidedly "homosexual."

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities