<<< >>>

{432}

Other Mammals

CARNIVORES

Wild Cats (Felids)

Wild Cats (Felids)

LION (Panthera leo)

IDENTIFICATION: A large wild cat (up to 550 pounds) with a prominent mane in males. DISTRIBUTION: Throughout Africa and in Gujarat, northwest India; vulnerable. HABITAT: Plains, savannas, scrub, open forest. STUDY AREAS: Serengeti National Park, Tanzania; Gir Wildlife Sanctuary, India; Gay Lion Farm, California; subspecies P.I. massaieus, the Masai Lion, and PJ. persica, the Asiatic Lion.

CHEETAH (Acinonyx jubatus)

IDENTIFICATION: A medium-sized wild cat with a sleek, greyhoundlike physique and a spotted coat DISTIBUTION-TION: Throughout Africa and sporadically in central Asia and the Middle East; vulnerable. HABITAT: Semidesert, grassland, steppes. STUDY AREAS: Serengeti National Park, Tanzania; Lion Country Safari, California; National Zoological Park, Washington, D.C.; Hogle Zoo, Utah; subspecies A.j. jubatus, the African Cheetah.

Social Organization

Lions have two distinct forms of social

organization. Some individuals are RESIDENTS, living in prides of up to a dozen

or more adult females (usually all related to one another) with their cubs,

along with an associated COALITION of one to nine adult males. Other Lions are

NOMADS, ranging widely as solitary individuals or pairs. Female Cheetahs are

largely solitary, while males are either RESIDENTS (with their own territories)

or FLOATERS (without resident territories). Some males associate in groups of

two to three (occasionally four) animals, often littermates (see below). The

mating system is promiscuous or polygamous: males and females {433}

generally mate with multiple partners, no long-term heterosexual bonds are formed, and males do not typically participate in parenting.

Description

Behavioral Expression: In female Lions, homosexual interactions are often initiated by one female pursuing another and crawling under her to encourage the other female to mount her. When mounting another female, a Lioness displays a number of behaviors also associated with heterosexual mating, including gently biting the mountee on the neck, growling, making pelvic thrusts, and rolling on her own back afterward. Sometimes Lionesses take turns mounting each other. Because most females in a pride are related to each

other — on average about as closely related as cousins — homosexual behavior among Lionesses may be largely incestuous. Among male pride-mates (residents), homosexual activity often begins with a great deal of affectionate activity (which is also a component of "greetings" interactions between males). This includes mutual head-rubbing (often accompanied by a low moaning or humming noise), presentation of the hindquarters to the other male, sliding and rubbing against each other, circling one another, and rolling on the back with an erect penis. This may lead to intense caressing and eventually mounting of one male by the other, including pelvic thrusting. Sometimes three males rub and roll together, mounting each other in turn. A male Lion sometimes courts a particular individual, keeping company with him for several days while engaging in sexual behavior. He typically defends his partner against intruding males, and often other males in the group will join him in attacking any interfering males. Because male pride-mates, like females, are usually related to each other (as close, on average, as half brothers), this activity may also be incestuous. Nomadic male Lions also form long-lasting platonic "companionships" with other males, spending nearly all of their time together; these male pair- or trio-bonds are generally stronger than heterosexual bonds between residents. Companions are usually close in age; some are pride-mates or brothers, although about half of all companionships include unrelated individuals. Females occasionally form companionships with each other as well.

Female Cheetahs sometimes court other females, including participation in courtship chases, play-fighting, and mating circles. Courtship chases take place in the early morning, late afternoon, or on moonlit nights; groups of Cheetahs — in — cluding females — chase a female in heat for up to 150 yards. This may be interspersed with mock-fighting, in which the courting animals (females or males) rise up on their hind legs and drop their forelegs on the female being courted. Females also sometimes join MATING CIRCLES, where the animals lie in a circle around the courted female, often while the males take turns fighting each other. A female Cheetah may also mount another female who is in heat, clasping her with the forelegs, gently biting the scruff of her neck (as in heterosexual copulation), and thrusting against her. Male homosexual mounting occurs as well, and one male may also mount another male that is in the act of mating with a female. During courtship interactions, males also sometimes lick and nuzzle another {434}

male's genitals while closely following him, occasionally exhibiting an erection while doing so.

Male Cheetahs often live in permanent partnerships or COALITIONS, consisting of a pair or trio of animals; about 30 percent of these associations include animals that are not related to each other, while the remainder consist of brothers. Partners are strongly bonded to one another and probably remain together for life. Spending almost all (93 percent) of their time in each other's company, male pair-mates frequently groom one another (licking each other's face and neck), defend each other in fights, and prefer resting together in close contact (even if this means that one of them will not be fully shaded against the harsh midday sun). Bonded males also become strongly distressed when separated, continuously searching and calling loudly for one another with birdlike yip or chirp calls. On being reunited, they may engage in a variety of affectionate and/or sexual activities, including reciprocal mounting with erections, face-rubbing, and STUTTERING (a purrlike vocalization often associated with sexual excitement). These activities appear to be more common between siblings than nonsiblings. Very rarely, paired males may temporarily adopt or look after lost cubs (most other parents in this species — foster or otherwise — are single mothers).

Frequency: In Lions, homosexual behavior in females is fairly common in captivity, while in the wild, two Lionesses were observed to mount each other three times over two days. In males, homosexual mounting may account for up to 8 percent of all mounting episodes. About 47 percent of all companionships involving adult nomadic Lions are between males, and about 37 percent are between females. Homosexual behavior (courtship and sexual) in Cheetahs is also quite frequent (at least in captive or semiwild conditions). In the wild, 27-40 percent of males live in same-sex pairs while 16-19 percent live in same-sex trios. In one study, 1 out of 11 instances of foster-parenting involved a pair of males looking after a cub (representing perhaps less than 1 percent of all families, adoptive and nonadoptive).

Orientation: Female Lions and male Cheetahs that participate in homosexual mounting may be bisexual, since same-sex activity sometimes alternates (or co-occurs) with heterosexual mounting in the same session. Some female Lions react aggressively to homosexual overtures and therefore these individuals are probably predominantly heterosexual. However, other females engage in same-sex mounting even in the presence of males, indicating more of a "preference" for homosexual activity. Many male Cheetahs living in partnerships do court and mate with females. However, pairs or trios of males are only with females 9 percent of the time, and they may experience reduced heterosexual mating opportunities compared to single males. Moreover, same-sex coalitions usually constitute life-long pair-bonds (which are not found between males and females in this species). Only about half of all companionships of two to three male Lions ever become residents that mate with a pride of females. Those that don't may associate exclusively with other males for most of their lives, while some that do join a pride may participate in both same-sex and opposite-sex activities.

{435}

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

More than 60 percent of male Lions (solitary or in companionships) do not become residents during their lives and therefore do not participate in breeding. When they do, however, Lions have extraordinarily high heterosexual copulation rates. The female may mate as often as four times an hour when she is in heat over a continuous period of three days and nights (without sleeping), and sometimes with up to five different males — far in excess of the amount required if mating were simply for fertilization. A number of other nonprocreative sexual behaviors occur in these felids as well. Lions sometimes mate during pregnancy (up to 13 percent of all sexual activity), and as much as 80 percent of all heterosexual mating in some populations may not result in reproduction. In fact, following arrival of new males in a pride, females often increase their sexual activity while reducing their fertility (by failing to ovulate). In addition, "oral sex" is a feature of heterosexual foreplay — female Lions may lick and rub the male's genitals, while Cheetahs of both sexes lick their partner's genitals as part of heterosexual courtship. Male Lions have also been observed masturbating in captivity: an unusual technique is used, in which the Lion lies on his back and rolls his hindquarters up above his head, so that he can rub his penis with one of his front legs.

In wild Cheetahs, incestuous activity occasionally takes place when adult males try to mount their mothers, who typically react aggressively to such advances. In fact, heterosexual relations are in general characterized by a great deal of aggression between the sexes. In Lions, heterosexual copulation is often accompanied by snarling, biting, growling, and threats, and sometimes the female actually wheels around and slaps the male. During Cheetah courtship chases, males often knock females down and slap them, and these interactions may develop into full-scale fights. When the female is not in heat, the two sexes live largely segregated lives. Family life in these species may also be fraught with violence: infanticide occurs in Lions (where it accounts for more than a quarter of all cub deaths) as well as Cheetahs. Abandonment by their mother is the second highest cause of cub mortality in Cheetahs, and mother Cheetahs occasionally eat their own cubs if they have been killed by a predator (adult male Cheetahs also sometimes cannibalize each other). However, female Lions often participate in productive alternative family arrangements amongst themselves, such as communal care and suckling of young, as well as the formation of

CRÈCHES or nursery groups. Female Cheetahs also sometimes (reluctantly) adopt orphaned or lost cubs.

Sources (* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

* Benzon, T. A., and R. F. Smith (1975) "A Case of Programmed Cheetah Acinonyx jubatus Breeding." International Zoo Yearbook 15:154-57.

Bertram, B. C. R. (1975) "Social Factors Influencing Reproduction in Wild Lions." Journal of Zoology, London 177:463-82.

* Caro, T. M. (1994) Cheetahs of the Serengeti Plains: Group Living in an Asocial Species. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. {436}

* --- (1993) "Behavioral Solutions to Breeding Cheetahs in Captivity: Insights from the Wild." Zoo Biology 12:19-30.

* Caro, T. M., and D. A. Collins (1987) "Male Cheetah Social Organization and Territoriality." Ethology 74:52-64.

* --- (1986) "Male Cheetahs of the Serengeti." National Geographic Research 2:75-86.

* Chavan, S. A. (1981) "Observation of Homosexual Behavior in Asiatic Lion Panthera leo persica." Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 78:363-64.

* Cooper, J. B. (1942) "An Exploratory Study on African Lions." Comparative Psychology Monographs 17:1 — 48.

Eaton, R. L. (1978) "Why Some Felids Copulate So Much: A Model for the Evolution of Copulation Frequency." Carnivore 1:42-51.

* --- (1974a) The Cheetah: The Biology, Ecology, and Behavior of an Endangered Species. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

* --- (1974b) "The Biology and Social Behavior of Reproduction in the Lion." In R. L. Eaton, ed., The World's Cats, vol. 2: Biology, Behavior, and Management of Reproduction, pp. 3-58. Seattle: Woodland Park Zoo.

* Eaton, R. L., and S. J. Craig (1973) "Captive Management and Mating Behavior of the Cheetah." In R. L. Eaton, ed., The World's Cats, vol. 1: Ecology and Conservation, pp. 217-254. Winston, Oreg.: World Wildlife Safari.

Herdman, R. (1972) "A Brief Discussion on Reproductive and Maternal Behavior in the Cheetah Acinonyx jubatus." In Proceedings of the 48th Annual AAZPA Conference (Portland, OR), pp. 110-23. Wheeling, W. Va.: American Association of Zoological Parks and Aquariums.

Laurenson, M. K. (1994) "High Juvenile Mortality in Cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus) and Its Consequences for Maternal Care." journal of Zoology, London 234:387-408.

Morris, D. (1964) "The Response of Animals to a Restricted Environment." Symposia of the Zoological Society of London 13:99-118.

Packer, C., L. Herbst, A. E. Pusey, J. D. Bygott, J. P. Hanby, S. J. Cairns, and M. B. Mulder (1988) "Reproductive Success of Lions." In T. H. Clutton-Brock, ed., Reproductive Success: Studies of Individual Variation in Contrasting Breeding Systems, pp. 363-83. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Packer, C., and A. E. Pusey (1983) "Adaptations of Female Lions to Infanticide by Incoming Males." American Naturalist 121:716-28.

--- (1982) "Cooperation and Competition Within Coalitions of Male Lions: Kin Selection or Game Theory?" Nature 296:740-42.

Pusey, A. E., and C. Packer (1994) "Non-Offspring Nursing in Social Carnivores: Minimizing the Costs." Behavioral Ecology 5:362-74.

* Ruiz-Miranda, C. R., S. A. Wells, R. Golden, and J. Seidensticker (1998) "Vocalizations and Other Behavioral Responses of Male Cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus) During Experimental Separation and Reunion Trials." Zoo Biology 17:1-16.

* Schaller, G. B. (1972) The Serengeti Lion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Subba Rao, M. V., and A. Eswar (1980) "Observations on the Mating Behavior and Gestation Period of the Asiatic Lion, Panthera leo, at the Zoological Park, Trivandrum, Kerala." Comparative Physiology and Ecology 5:78-80.

Wrogemann, N. (1975) Cheetah Under the Sun. Johannesburg: McGraw-Hill.

{437}

Wild Dogs (Canids)

Wild Dogs (Canids)

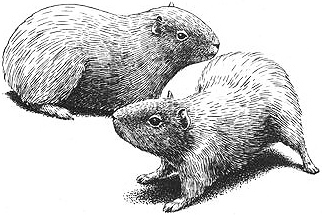

RED FOX (Vulpes vulpes)

IDENTIFICATION: A small canid (body length up to 3 feet) with a bushy tail and a reddish brown coat (although some variants are silvery or black). DISTRIBUTION: Throughout most of Eurasia, northern Africa, and North America. HABITAT: Variable, including forest, tundra, prairie, farmland. STUDY AREA: Oxford University, England.

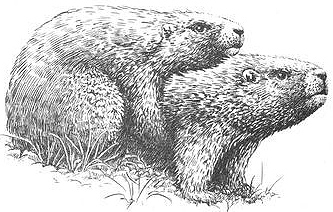

(Gray) WOLF (Canis luous)

IDENTIFICATION: The largest wild canid (reaching up to 7 feet in length) with a gray, brown, black, or white coat. DISTRIBUTION: Throughout most of the Northern Hemisphere. HABITAT: Widely varied, excepting tropical forests and deserts. STUDY AREAS: Bavarian Forest National Park, Germany; Basel Zoo, Switzerland; subspecies C.I. lupus, the Common Wolf.

BUSH DOG (Speothos venaticus)

IDENTIFICATION: A small (3 foot long), reddish brown, bearlike canid with short legs and tail. DISTRIBUTION: Northern and eastern South America; vulnerable. HABITAT: Forest, savanna, swamp, riverbanks. STUDY AREA: London Zoo, England.

Social Organization

Red Fox society is characterized by highly complex and flexible living arrangements and social interactions, varying both between and within populations. Many Foxes live in groups with several, often related, adult females and one male (or rarely several); mated pairs are characteristic of other populations. Mating systems range from monogamy to polygamy. Wolves have a highly developed social system revolving around the pack, a group of usually a dozen or so individuals consisting of a mated pair and up to two generations of their offspring; occasionally, a few unrelated adults also live in the pack. Much less is known of the social life of wild Bush Dogs, although it appears that they, too, live in groups (possibly also pairs) and hunt in packs of usually a dozen individuals (though much larger groups containing hundreds of dogs have also been reported).

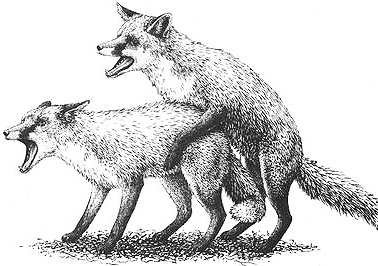

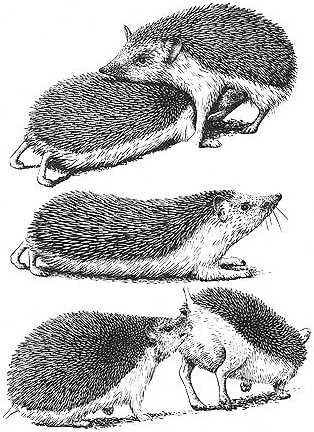

Because sexual activity in Red Foxes usually takes place at night, scientists were only able to document homosexual activity by using remote-control video cameras, set up in an enclosure illuminated by infrared light. In these two stills taken from the videotape, a younger female Red Fox mounts her mother.

{438}

Description

Behavioral Expression: When the breeding female in a Red Fox group comes into heat, both the male and female group members become sexually interested in her. Homosexual interactions involve the younger females — usually her daughters — running up to the vixen in heat, sniffing her genitals and mounting her. Although the mounting female clasps the other tightly, the older vixen usually responds to these sexual advances aggressively (as she does to most sexual approaches by males) by rearing up and "boxing" with the other female while gaping her mouth. The younger females may also mount each other, all the while making staccato, rasping click sounds known as GECKERING and SNIRKING. Pairs of Red Fox females also sometimes coparent their young, sharing a den, rearing their cubs together, bringing food for each other, and even suckling each other's young. Although coparents are often related to each other, some may not be relatives.

Male Wolves often mount each other when the highest-ranking female in their pack comes into heat (a time when heterosexual activity also reaches its peak). As in Red Foxes, homosexual activity may be incestuous, since the males in the pack are often related to each other. A male Wolf sometimes also mounts another male when the latter is mounting a female. Male Bush Dogs have also been observed mounting each other, often accompanied by playful nipping of the legs or hindquarters.

Frequency: In captivity, homosexual mounting in Red Foxes and Wolves occurs frequently when the breeding female is in heat. In Bush Dogs, mounting between males is less common. The prevalence of these behaviors in the wild is not known.

Orientation: Many female Red Foxes that mount other females may be exclusively same-sex oriented, since such younger or lower-ranking individuals usually do not mate with males. For some females, this homosexual orientation may be longlasting — perhaps even continuing for a female's entire life — since as many as 50-70 percent of vixens never leave their home groups to begin breeding on their own. Male Wolves that mount each other are bisexual, also showing sexual interest in females. However, their heterosexual activity is limited to the highest-ranking breeding female: males routinely ignore lower-ranking females in favor of homosexual activity.

A female Red Fox mounting another female

{439}

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

In all three of these wild dog species, reproductive suppression is a prominent feature of the social system. For example, only a fraction of female Red Foxes reproduce — a third or more of all vixens (depending on the population) are non-breeders, and in some areas as many as 95 percent of adult females do not reproduce. There are multiple mechanisms for this "birth control." In some cases, nonbreeding females simply do not mate, or else they fail to come into heat (a similar phenomenon occurs in Bush Dogs). In other cases, females become pregnant, but routinely abort their fetuses or abandon their young once they are born. Neglect or abuse of pups (leading to their death) has been documented in both Red Foxes and Bush Dogs, as well as cannibalism (in Red Foxes). In Wolves, the highest-ranking individuals (especially males) often prevent other animals from mating by intruding or attacking them directly; as many as a quarter of all mounts may be interrupted this way. In other cases, Wolves simply show no sexual interest in the opposite sex; these and other factors function to curtail reproduction in 40-80 percent of all packs. Breeding may also be inhibited by an incest taboo when a pack comes to consist entirely of closely related individuals (usually siblings). However, mother-son and brother-sister matings have occasionally been observed, and some packs may be highly inbred. In both Red Foxes and Wolves (and to a lesser extent, Bush Dogs), nonbreeding animals sometimes help the breeding female raise her young, including feeding, guarding, and "baby-sitting" them. There are even cases of a female Red Fox adopting an entire litter after their biological mother has died or been killed. However, some nonbreeding Red Foxes do not contribute any such care, and there is actually some evidence that more offspring may be successfully reared when there are fewer such "helpers" present in the group. Nonbreeding lone Wolves that do not act as helpers may constitute as much as 28 percent of some populations.

In addition to patterns of reproductive suppression, a number of nonreproductive heterosexual activities also occur in these canids. About 8 percent of female Red Foxes mate outside of the breeding period (this practice occurs in Wolves as well). Because males also have a sexual cycle ensuring that they cannot produce sperm during this time, such matings are definitively nonprocreative. About half of all heterosexual mounts in Wolves do not involve thrusting, penetration, or ejaculation; female Wolves also sometimes mount and thrust against males (REVERSE mounting). When mating does occur in Wolves and Red Foxes, individuals often engage in multiple copulations (i.e., more than the number of times simply required for fertilization). These often involve "copulatory ties" that keep the partners joined at the genitals for long periods. Heterosexual relations are sometimes fraught with difficulty, for example when female Red Foxes aggressively gape at males trying to mount them, or when both male and female Wolves display indifference or aggression toward animals trying to mate with them. In fact, one study showed that less than 3 percent of all heterosexual courtships in Wolves actually result in copulation.

{440}

Other Species

Several forms of intersexuality or transgender occasionally occur in Raccoon Dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides). Some individuals, for example, combine female genitals with testes, while others have a mosaic chromosome pattern that combines a male pattern (XY) with a joint male-female pattern (XXY).

Sources (* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

Creel, S., and D. Macdonald (1995) "Sociality, Group Size, and Reproductive Suppression Among Carnivores." Advances in the Study of Behavior 24:203-57.

Derix, R., J. van Hooff, H. de Vries, and J. Wensing (1993) "Male and Female Mating Competition in Wolves: Female Suppression vs. Male Intervention." Behavior 127:141-74.

Druwa, P. (1983) "The Social Behavior of the Bush Dog (Speothos)." Carnivore 6:46-71.

* Fentener van Vlissengen, J. M., M. A. Blankenstein, J. H. H. Thijssen, B. Colenbrander, A. J. E. P. Verbruggen, and C. J. G. Wensing (1988) "Familial Male Pseudohermaphroditism and Testicular Descent in the Raccoon Dog (Nyctereutes)." Anatomical Record 222:350-56.

van Hooff, J. A. R. A. M., and J. A. B. Wensing (1987) "Dominance and Its Behavioral Measures in a Captive Wolf Pack." In H. Frank, ed., Man and Wolf: Advances, Issues, and Problems in Captive Wolf Research, pp. 219-52. Dordrecht: Dr W. Junk.

* Kleiman, D. G. (1972) "Social Behavior of the Maned Wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus) and Bush Dog (Speothos venaticus): A Study in Contrast." Journal of Mammalogy 53:791-806.

Lloyd, H. G. (1975) "The Red Fox in Britain." In M. W. Fox, ed., The Wild Canids: Their Systematics, Behavioral Ecology, and Evolution, pp. 207-15. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Macdonald, D. W. (1996) "Social Behavior of Captive Bush Dogs (Speothos venaticus)." Journal of Zoology, London 239:525-43.

* --- (1987) Running with the Fox. New York: Facts on File.

* --- (1980) "Social Factors Affecting Reproduction Amongst Red Foxes (Vulpes vulpes L., 1758)." In E. Zimen, ed., The Red Fox: Symposium on Behavior and Ecology, pp. 123-75. Biogeographica no. 18. The Hague: Dr W. Junk.

--- (1979) "'Helpers' in Fox Society." Nature 282:69-71.

--- (1977) "On Food Preference in the Red Fox." Mammal Review 7:7-23.

Macdonald, D. W., and P. D. Moehlman (1982) "Cooperation, Altruism, and Restraint in the Reproduction of Carnivores." In P. P. G. Bateson and P. H. Klopfer, eds., Perspectives in Ethology, vol. 5: Ontogeny, pp. 433-67.

Mech, L. D. (1970) The Wolf: The Ecology and Behavior of an Endangered Species. New York: Natural History Press.

Packard, J. M., U. S. Seal, L. D. Mech, and E. D. Plotka (1985) "Causes of Reproductive Failure in Two Family Groups of Wolves." Zeitchrift fur Tierpsychologie 68:24-40.

Packard, J. M., L. D. Mech, and U. S. Seal (1983) "Social Influences on Reproduction in Wolves." In L. N. Carbyn, ed., Wolves in Canada and Alaska: Their Status, Biology, and Management, pp. 78-85. Canadian Wildlife Service Series no. 45. Ottawa: Canadian Wildlife Service.

Porton, I. J., D. G. Kleiman, and M. Rodden (1987) "Aseasonality of Bush Dog Reproduction and the Influence of Social Factors on the Estrous Cycle." Journal of Mammalogy 68:867-71.

Schantz, T. von (1984) "'Non-Breeders' in the Red Fox Vulpes vulpes: A Case of Resource Surplus." Oikos 42:59-65.

--- (1981) "Female Cooperation, Male Competition, and Dispersal in the Red Fox Vulpes vulpes." Oikos 37:63-68.

* Schenkel, R. (1947) "Ausdrucks-Studien an Wolfen: Gefangenschafts-Beobachtungen [Expression Studies of Wolves: Captive Observations]." Behavior 1:81-129.

Schotte, C. S., and B. E. Ginsburg (1987) "Development of Social Organization and Mating in a Captive Wolf Pack." In H. Frank, ed., Man and Wolf: Advances, Issues, and Problems in Captive Wolf Research, pp. 349-74. Dordrecht: Dr W. Junk.

Sheldon, J. W. (1992) Wild Dogs: The Natural History of the Nondomestic Canidae. San Diego: Academic Press.

Smith, D., T. Meier, E. Geffen, L. D. Mech, J. W. Burch, L. G. Adams, and R. K. Wayne (1997) "Is Incest Common in Gray Wolf Packs?" Behavioral Ecology 8:384-91.

Storm, G. L., and G. G. Montgomery (1975) "Dispersal and Social Contact Among Red Foxes: Results From Telemetry and Computer Simulation." In M. W. Fox, ed., The Wild Canids: Their Systematics, Behavioral Ecology, and Evolution, pp. 237-46. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. {441}

* Wurster-Hill, D. H., K. Benirschke, and D. I. Chapman (1983) "Abnormalities of the X Chromosome in Mammals." In A. A. Sandberg, ed., Cytogenetics of the Mammalian X Chromosome, Part B, pp. 283-300. New York: Alan R. Liss.

* Zimen, E. (1981) The Wolf: His Place in the Natural World. London: Souvenir Press.

* --- (1976) "On the Regulation of Pack Size in Wolves." Zeitschrift fur Tierpsychologie 40:300-341.

Bears

Bears

GRIZZLY BEAR (Ursus arctos)

IDENTIFICATION: A huge bear (7-10 feet tall) with dark brown, golden, cream, or black fur. DISTRIBUTION: Northern North America, Europe, central Asia, Middle East, north Africa. HABITAT: Tundra, forests. STUDY AREA: Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming; subspecies U.a. horribilis.

(American) BLACK BEAR (Ursus americanus)

IDENTIFICATION: A smaller bear (4-6 feet) with coat color ranging from black to gray, brown, and even white. DISTRIBUTION: Canada and northern, eastern, and southwestern United States. HABITAT: Forest. STUDY AREA: Jasper National Park, Alberta; Prince Albert National Park, Saskatchewan, Canada; subspecies

U.a. altifrontalis.

Social Organization

Grizzly Bears and Black Bears are largely solitary animals. Some Grizzly populations, however, tend to aggregate around abundant food sources such as salmon, marine mammals (stranded onshore), garbage dumps, and even insect swarms; fairly complex social interactions may develop in these contexts. The heterosexual mating system is polygamous, as both males and females generally mate with multiple partners; males do not contribute to parenting.

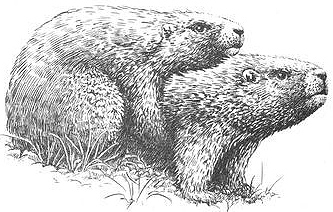

A two-mother family: bonded female Grizzly Bears in Wyoming with their four cubs

Description

Behavioral Expression: Female Grizzly Bears sometimes bond with each other and raise their young together as a single family unit. The two mothers become {442}

inseparable companions, traveling and feeding together throughout the summer and fall seasons as they share in the parenting of their cubs. Female companions have not been observed interacting sexually with one another, however. A bonded pair jointly defends their food (such as Elk or Bison carcasses), and the two females also protect one another and their offspring (including defending them against attacks by Grizzly males). The cubs regard both females as their parents, following and responding to either mother equally; bonded females occasionally also nurse each other's cubs. If one female dies, her companion usually adopts her cubs and looks after them along with her own.

As winter approaches and Grizzlies prepare for hibernation, female coparents often continue to associate with one another. Foraging together late into the fall, they are apparently reluctant to end their relationship and may even delay the onset of their own sleep. Although paired females do not hibernate together, they frequently visit each other (with their cubs) prior to hibernation, staying nearby while their partner prepares her den. They also sleep together outside their denning sites during this final preparatory period and only retreat to their separate dens once the snow gets too deep. Most Grizzlies seek solitude prior to hibernating and locate their winter dens miles away from each other (and with rugged terrain separating them), but bonded females often hibernate relatively close to one another. Such females have even been known to abandon their traditional denning locations to be nearer to their coparent. One female, for example, moved her usual den site more than 14 miles to be closer to her companion. Pair-bonds are not usually resumed after hibernation, although one female may adopt her companion's yearling offspring the following season. The average age of a bonded female is about 11 years, although Grizzlies as young as 5 and as old as 19 have formed bonds with other females. Companions may be of the same age, or one female might be several years older than the other. Sometimes more than two females are involved: three Grizzlies may form a strongly bonded "triumvirate," and groups of four or five females have even been known to associate (sometimes also forming pair- or trio-bonds within such a group).

Younger male Black Bears (adolescents and cubs) sometimes mount their siblings, both male and female. One male approaches another with his ears in a {443}

CRESCENT configuration (facing forward and perpendicular from the head), then rears up on his hind legs in a STANDING OVER position, in which he places his front paws on the other male's back. This develops into sexual mounting as he clasps his partner and gently bites the loose skin on his shoulder, sometimes making pelvic thrusts. The other male often rolls over and begins play-fighting with the mounting male, pawing and biting at him.

Intersexual or hermaphrodite Black and Grizzly Bears occur in some populations. These individuals are genetically female and have female internal reproductive organs, combined with various degrees of external male genitalia. In some cases, they have a penislike organ (complete with a penis bone or BACULUM) that is not connected to the internal reproductive organs, while in others the penis is more fully developed, serving as both a genital orifice connected to the womb as well as a urinary organ. Most transgendered Bears are mothers, mating with males and bearing offspring. Some individuals actually copulate and give birth through their "penis": their male partner inserts his organ into the tip of the intersexual Bear's phallus, and the resulting offspring emerge through the penis as well.

Frequency: Female bonding and coparenting among Grizzly Bears occur sporadically. In a 12-year study of one population, for example, bonds between females were observed during 4 of those years (a third of the study period), with roughly 20 percent of all females participating in same-sex bonding and coparenting at some point in their life (usually 1-2 years out of an adult life span of 7-12 years). About 9 percent of all Grizzly cubs are raised in families headed by two (or more) pair-bonded mothers (constituting about 4 percent of all families). Sexual activity between younger male Black Bears occurs only occasionally, comprising perhaps less than 2 percent of their play. The incidence of intersexual Bears is probably sporadic as well, although some populations appear to have fairly high proportions: in Alberta, for example, researchers found that 4 out of 38 Black Bears (11 percent) and 1 of 4 Grizzlies were transgendered.

Orientation: Extended heterosexual pair-bonding and parenting by male-female couples do not occur among Grizzly Bears; however, only a subset of females bond with each other and coparent their young. Thus, some individuals are probably more inclined to form same-sex attachments than others, and these females may even develop same-sex bonds on more than one occasion. Although such females mate with males (and may not bond with females in other years), their primary social relationship during the time they are bonded is with their female companion (and their young). Male Black Bears participate in homosexual mounting only as youngsters and adolescents; most probably go on to mate heterosexually as adults.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Some Grizzly and Black Bear populations have significant numbers of nonbreeding animals. Each year, perhaps as many as one-third to one-half of all female Grizzlies do not mate or are otherwise nonreproductive (including copulating with males without becoming pregnant), and some individuals do not breed during {444}

their whole lives. In some Black Bear populations, only 16-50 percent of the adult females reproduce each year, and many skip breeding for several years. Female Bears who do become pregnant exhibit DELAYED IMPLANTATION — the fertilized embryo ceases development for about five months before implanting in the uterus. In some cases embryos are reabsorbed, aborted, or prevented from implanting rather than carried to term (e.g., when food supplies are inadequate). In addition, many female Grizzlies and Black Bears delay reproducing anywhere from one to four years after they become sexually mature. Juvenile (sexually immature) Black and Grizzly Bears also engage in sexual activity with each other, including mounting and licking of the vulva. Among adult male Grizzly Bears, higher-ranking individuals often have lower copulation rates because of their preoccupation with aggressive interactions, and in some populations top-ranked males may actually go entire breeding seasons without mating at all. When mating does take place, one partner may display indifference or refusal, and as many as 47 percent of all copulations are incomplete in that they do not involve full penetration or ejaculation. Occasionally, a particularly aggressive male will force a female to mate with him, although females usually have control of the interaction. In fact, females often mate with multiple partners — as many as eight males in a single breeding season for Grizzlies, four to six for Black Bears — and cubs belonging to the same litter may be fathered by different males. Nevertheless, male Black and Grizzly Bears can become violent toward females and cubs, occasionally even killing and cannibalizing adults and/or young. Female Black Bears also sometimes kill cubs that are not their own (especially during the nursing period), although it is not uncommon for mothers of both species to adopt cubs that have been orphaned or abandoned.

Other Species

Intersexual or transgendered individuals also occur among Polar Bears (Ursus maritimus), comprising about 2 percent of some populations.

Sources (* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

Alt, G. L. (1984) "Cub Adoption in the Black Bear." Journal of Mammalogy 65:511-12.

Brown, G. (1993) The Great Bear Almanac. New York: Lyons and Beuford.

* Cattet, M. (1988) "Abnormal Sexual Differentiation in Black Bears (Ursus americanus) and Brown Bears (Ursus arctos)." Journal of Mammalogy 69:849-52.

* Craighead, F. C., Jr. (1979) Track of the Grizzly. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books. * Craighead, F. C., Jr., and J. J. Craighead (1972) "Grizzly Bear Prehibernation and Denning Activities as Determined by Radiotracking." Wildlife Monographs 32:1-35

* Craighead, J. J., J. S. Sumner, and J. A. Mitchell (1995) The Grizzly Bears of Yellowstone: Their Ecology in the Yellowstone Ecosystem, 1959-1992. Washington, D.C. and Covelo, Calif.: Island Press.

* Craighead, J. J., M. G. Hornocker, and F. C. Craighead Jr. (1969) "Reproductive Biology of Young Female Grizzly Bears." Journal of Reproduction and Fertility, suppl. 6:447-75.

Egbert, A. L. (1978) "The Social Behavior of Brown Bears at McNeil River, Alaska." Ph.D. thesis, Utah State University.

Egbert, A. L., and A. W. Stokes (1976) "The Social Behavior of Brown Bears on an Alaskan Salmon Stream." In M. R. Pelton, J. W. Lentfer, and G. E. Folk, eds., Bears — Their Biology and Management: Papers from the Third International Conference on Bear Research and Management, pp. 41-56. Morges, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.

Erickson, A. W., and L. H. Miller (1963) "Cub Adoption in the Brown Bear." Journal of Mammalogy 44:584-85. {445}

Goodrich, J. M., and S. J. Stiver (1989) "Co-occupancy of a Den by a Pair of Great Basin Black Bears." Great Basin Naturalist 4:390-91.

* Henry, J. D., and S. M. Herrero (1974) "Social Play in the American Black Bear: Its Similarity to Canid Social Play and an Examination of Its Identifying Characteristics." American Zoologist 14:371-89.

Jonkel, C. J., and I. McT. Cowan (1971) "The Black Bear in the Spruce-Fir Forest." Wildlife Monographs 27:1-57.

Rogers, L. (1976) "Effects of Mast and Berry Crop Failures on Survival, Growth, and Reproductive Success of Black Bears." Transactions of the North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conference 41:431-38.

Schenk, A., and K. M. Kovacs (1995) "Multiple Mating Between Black Bears Revealed by DNA Fingerprinting." Animal Behavior 50:1483-90.

Stonorov, D., and A. W. Stokes (1972) "Social Behavior of the Alaska Brown Bear." In S. Herrero, ed., Bears — Their Biology and Management: Papers from the Second International Conference on Bear Research and Management, pp. 232-42. Morges, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.

Tait, D. E. N. (1980) "Abandonment as a Reproductive Tactic — the Example of Grizzly Bears." American Naturalist 115:800-808.

Wimsatt, W. A. (1969) "Delayed Implantation in the Ursidae, with Particular Reference to the Black Bear (Ursus americanus Pallus)." In A. C. Enders, ed., Delayed Implantation, pp. 49-76. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hyenas

Hyenas

SPOTTED HYENA (Crocuta crocuta)

IDENTIFICATION: A yellowish brown hyena with spotted flanks and back, a strongly sloping body profile, and rounded ears; females typically heavier than males. DISTRIBUTION: Sub-Saharan Africa. HABITAT: Open country, including plains, semidesert, savanna. STUDY AREAS: Kalahari and Gemsbok National Parks, South Africa and Botswana; University of California-Berkeley.

Social Organization

Spotted Hyenas live in matrilineal clans of 30-80 individuals. Females are dominant to males and remain in their home group for life, while males emigrate to single-sex groups during adolescence and then join other clans (usually for only a few years at a time) on reaching adulthood. This species has a highly organized {446}

social system, engaging in cooperative hunting and communal denning. The breeding system is polygynous: generally only one male in each clan mates with several females. Spotted Hyenas are largely nocturnal.

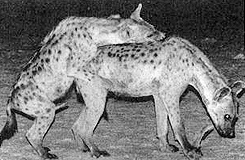

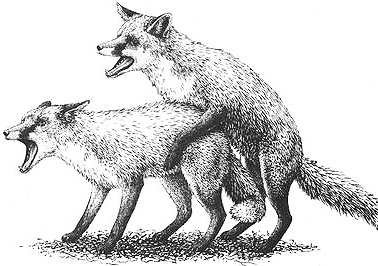

A younger female Spotted hyena (with erect clitoris) mounting an older female in southern Africa.

Description

Behavioral Expression: Female Spotted Hyenas have an extraordinary genital configuration that makes them superficially resemble males: the clitoris is 90 percent of the length of the male's penis (nearly seven inches long) and equal to it in diameter; it can be fully erected. In addition, the labia are fused to resemble a "scrotum" containing fat and connective tissue that give the appearance of testes. There is no vaginal opening — instead, the female mates and gives birth (as well as urinates) through the tip of her clitoris. Heterosexual mating is accomplished by retracting the clitoris inside the abdomen, essentially turning it inside out to form a passageway within which the male can insert his penis. Homosexual mounting between females also occurs in this species; in some cases, an adolescent or younger adult mounts an older one. During a homosexual encounter, one female approaches another with her clitoris erect, often "flipping" it up against her abdomen as a sign of sexual arousal (also seen in males preparing to mate). She may lick her partner on the back, then mount by rising up and clasping her front paws around the other female, resting her head on the other's neck, and thrusting against her. Clitoral penetration may also occur, though it is not common. Sometimes the female being mounted appears to be disinterested or nonchalant and may even wander off during mounting. These are also characteristics of heterosexual courtship and copulation — females often walk away or do not permit males to achieve penetration and, indeed, may be overtly aggressive toward them. Spotted Hyenas also perform a MEETING CEREMONY involving clitoral {447}

erection and genital licking: two females stand parallel to each other but with their heads in opposite directions so that they can access each other's genitals. One or both of them lifts up her hind leg and allows the other to sniff, nuzzle, and lick her erect clitoris and "scrotum" — sometimes for as long as half a minute at a time — occasionally accompanied by a soft groaning or whining sound. Although meeting ceremonies are sometimes performed between males and females (or between two males), they are most common between females.

Two female Spotted Hyenas nuzzling and sniffing each other's genitals during the "meeting ceremony"; note the erect clitoris and "scrotum" of the female raising her leg.

Frequency: All adult female Spotted Hyenas have enlarged clitorides and labial "scrota." Homosexual mounting probably occurs only occasionally in this species, although the majority of meeting ceremonies — anywhere from 55-95 percent — occur between adult females.

Orientation: Most females who participate in same-sex mounting and meeting ceremonies are probably functionally bisexual (if not predominantly heterosexual), also mating with males.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

The female Spotted Hyena's reproductive anatomy and genitals are not optimal for breeding. Heterosexual mating is often difficult, as males have trouble locating and penetrating the clitoral opening. In addition, many females (and infants) suffer severe trauma and even death during the birth process. Because there is no vaginal canal, Hyenas must give birth through the clitoris itself — an extraordinarily painful process, considering that the newborn's head is significantly larger than the diameter of the clitoris. This causes the clitoral head to rupture in all females during their first birth, and it is estimated that about 9 percent of females in the wild die during their first labor. In addition, the newborn must travel an extraordinarily long way through the female's birth canal, which makes a 180-degree turn to exit through the clitoris. Because the umbilical cord is less than a third of the length of the birth canal, many babies suffocate during birth — perhaps as many as 60 percent of infants are stillborn to first-time mothers, and a female's lifetime production of offspring may be reduced by as much as 25 percent because of such complications. Once born, up to a quarter of Spotted Hyena youngsters may be killed by their siblings, who are fiercely competitive and aggressive toward one another. Infanticide (usually by females) also occasionally occurs among Spotted Hyenas, and cannibalism has been reported as well. Most males do not breed at all: the social system of Spotted Hyenas is such that only one male in a clan gets to mate with the females (although other males may participate in heterosexual courtship). Some males, unable to copulate, engage in a form of "masturbation" in which they thrust their penis in the air and spontaneously ejaculate; others have been seen mounting cubs.

Other Species

Homosexual mounting occurs in Dwarf Mongooses (Helogale undulata), a weasel-like carnivore of Africa. In one group studied in captivity, 16 percent of mounting took place between animals of the same sex (mostly males, including {448}

brothers), and some individuals had preferred partners with whom they interacted most frequently. Homosexual behavior has also been observed in two other species of small carnivores: male Common Raccoons (Procyon lotor) and female Martens (Martes sp.).

Sources (* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

* Burr, C. (1996) A Separate Creation: The Search for the Biological Origins of Sexual Orientation. New York: Hyperion.

* East, M. L., H. Hofer, and W. Wickler (1993) "The Erect 'Penis' Is a Flag of Submission in a Female-Dominated Society: Greetings in Serengeti Spotted Hyenas." Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 33:355-70.

* Frank, L. G. (1996) "Female Masculinization in the Spotted Hyena: Endocrinology, Behavioral Ecology, and Evolution." In J. L. Gittleman, ed., Carnivore Behavior, Ecology, and Evolution, vol. 2, pp. 78-131. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

--- (1986) "Social Organization of the Spotted Hyena (Crocuta crocuta). I. Demography. II. Dominance and Reproduction." Animal Behavior 34:1500-1527.

Frank, L. G., J. M. Davidson, and E. R. Smith (1985) "Androgen Levels in the Spotted Hyena Crocuta crocuta: The Influence of Social Factors." Journal of Zoology, London 206:525-31.

Frank, L. G., and S. E. Glickman (1994) "Giving Birth Through a Penile Clitoris: Parturition and Dystocia in the Spotted Hyena (Crocuta crocuta)." Journal of Zoology, London 234:659-90.

Frank, L. G., S. E. Glickman, and P. Licht (1991) "Fatal Sibling Aggression, Precocial Development, and Androgens in Neonatal Spotted Hyenas." Science 252:702-04.

* Frank, L. G., S. E. Glickman, and I. Powch (1990) "Sexual Dimorphism in the Spotted Hyena (Crocuta crocuta )." Journal of Zoology, London 221:308-13.

* Frank, L. G., M. L. Weldele, and S. E. Glickman (1995) "Masculinization Costs in Hyenas." Nature 377:584-85.

* Glickman, S. E., C. M. Drea, M. Weldele, L. G. Frank, G. Cunha, and P. Licht (1995) "Sexual Differentiation of the Female Spotted Hyena (Crocuta crocuta)." Paper presented at the 24th International Ethological Conference, Honolulu, Hawaii.

* Glickman, S. E., L. G. Frank, K. E. Holekamp, L. Smale, and P. Licht (1993) "Costs and Benefits of 'Andro-genization' in the Female Spotted Hyena: The Natural Selection of Physiological Mechanisms." In P. P. G. Bateson, N. Thompson, and P. Klopfer, eds., Perspectives in Ethology, vol. 10: Behavior and Evolution, pp. 87-117. New York: Plenum Press.

* Hamilton, W. H., III, R. L. Tilson, and L.G. Frank (1986) "Sexual Monomorphism in Spotted Hyenas (Crocuta crocuta)." Ethology 71:63-73.

* Harrison Mathews, L. (1939) "Reproduction in the Spotted Hyena, Crocuta crocuta (Erxleben)." Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series B 230:1-78.

* Hofer, H., and M. L. East (1995) "Virilized Sexual Genitalia as Adaptations of Female Spotted Hyenas." Revue Suisse de Zoologie 102:895-906.

* Kinsey, A. C., W. B. Pomeroy, C. E. Martin, and P. H. Gebhard (1953) Sexual Behavior in the Human Female. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders.

Kruuk, H. (1975) Hyena. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

--- (1972) The Spotted Hyena, a Study of Predation and Social Behavior. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

* Mills, M. G. L. (1990) Kalahari Hyenas: Comparative Behavioral Ecology of Two Species. London: Unwin Hyman.

* Neaves, W. B., J. E. Griffin, and J. D. Wilson (1980) "Sexual Dimorphism of the Phallus in Spotted Hyena (Crocuta crocuta)." Journal of Reproduction and Fertility 59:509-13.

* Rasa, O. A. E. (1979a) "The Ethology and Sociology of the Dwarf Mongoose (Helogale undulata rufula)." Zeitschrift fur Tierpsychologie 43:337-406.

* --- (1979b) "The Effects of Crowding on the Social Relationships and Behavior of the Dwarf Mongoose (Helogale undulata rufula)." Zeitschrift fur Tierpsychologie 49:317-29.

{449}

MARSUPIALS

Kangaroos and Wallabies

Kangaroos and Wallabies

EASTERN GRAY KANGAROO (Macropus giganteus)

IDENTIFICATION: A large (over 3 foot tall) kangaroo with a gray coat and a hair-covered muzzle. DISTRIBUTION: Eastern Australia. HABITAT: Open grasslands, forest, woodland. STUDY AREAS: Nadgee Nature Reserve, New South Wales, Australia; Cowan Field Station (Muogammarra Nature Reserve) of the University of New South Wales.

RED-NECKED WALLABY (Macropus rufogriseus)

IDENTIFICATION: A smaller kangaroo (2 1/2 feet tall) with a reddish brown wash on its neck. DISTRIBUTION: Coastal southeastern Australia. HABITAT: Forest, brush areas. STUDY AREAS: Michigan State University; Cowan Field Station (Muogammarra Nature Reserve) of the University of New South Wales; subspecies M.r. rulogriseus, Bennett's Wallaby, and M.r. banksianus.

WHIPTAIL WALLABY (Macropus parryi)

IDENTIFICATION: A light gray kangaroo standing up to 3 feet tall, with a white facial stripe and a long, slender tail. DISTRIBUTION: Northeastern Australia. HABITAT: Open forest, savanna. STUDY AREA: Near Bonalbo, New South Wales, Australia.

Social Organization

Eastern Gray Kangaroos often associate in large groups of 40-50 animals — sometimes known as MOBS. These comprise smaller cosexual groups of up to 15 {450}

individuals, largely females and their young along with a few males. Some individuals are solitary. No pair-bonding occurs between males and females, and the mating system is polygamous or promiscuous. Whiptail Wallabies have a similar social organization, while Red-necked Wallabies are largely solitary (although groups of 8-30 animals may form at times).

Myth made real: a transgendered (intersexual) Eastern Gray Kangaroo. This animal has both a penis and a pouch (the latter usually found only in females). Chromosomally, it combines the female pattern (XX) with the male (XY) to yield an XXY pattern.

Description

Behavioral Expression: Pair-bonds occasionally develop between female Eastern Gray Kangaroos, involving frequent mutual grooming in which the partners affectionately lick, nibble, and rake the fur on each other's head and neck with their paws. Females in such associations also sometimes court and mount each other, and sexual activity may occur as well between females who are not necessarily bonded to one another. Significantly, heterosexual pair-bonds are not found in this species. In Red-necked Wallabies, females frequently mount each other: one female grabs the other from behind, wrapping her forearms around her partner's abdomen and tucking her forepaws inside her partner's thighs. This position resembles heterosexual copulation except that the mounting female is higher up on her partner's body. Sexual activity is often accompanied by grooming, fur-nibbling and licking, pawing, and nosing of the partner. Males also sometimes mount one another, usually during play-fights in which the partners gently push, wrestle, or "box" one another with their forearms. Occasional affectionate activities such as grooming, licking, embracing, and touching also take place during these sessions, and sometimes one male will sniff or nuzzle the other's scrotum. Courtship and sexual interactions between male Whiptail Wallabies involve TAIL-LASHING, a sinuous, sideways movement of the tail indicating sexual arousal, often accompanied by an erection. Mounting also occurs; one male sometimes presents his hindquarters to the other by crouching with his chest on the ground and raising his rump. Prior to mounting, a male frequently sniffs the other male's scrotum (as in Red-necked Wallabies). Swept up in a courtship frenzy, males also sometimes embark on homosexual chases as a part of heterosexual interactions. A group of males will be pursuing a female in heat, furiously circling and dashing after her at breakneck speed; occasionally, other males on the sidelines are then drawn into the excitement of these wild chases — and they are as likely to pursue other males as they are the female.

In Eastern Gray Kangaroos, intersexual or hermaphrodite individuals also occur: some animals, for example, have both a penis and a pouch (the latter usually found only in females), mammary glands, and testes, all combined with body proportions that are generally intermediate between male and female. Chromosomally, these individuals have a mosaic of the female type (XX), the male type (XY), and a combined XXY pattern.

Frequency: Female homosexual mounting in Eastern Gray Kangaroos occurs sporadically: in one study of a wild population, for example, homosexual behavior was recorded eight times during four months of observation. It should be noted, {451}

however, that heterosexual mating is rarely observed as well: only one male-female mating was seen during that same time, while only three heterosexual copulations were recorded during a three-year study of Red-necked Wallabies. In captivity, mounting between female Red-necked Wallabies is quite common, but male homosexual activity is much less frequent. During play-fights between males, courtship and sexual behaviors occur roughly once every five hours of activity. Homosexual mounts between males account for about 1 percent of all mounting activity in Whiptail Wallabies.

Orientation: In captive groups of Eastern Gray Kangaroos (which included both sexes), four of six females formed same-sex pairs. Male Red-necked Wallabies may be sequentially bisexual during their lifetimes: sexual interactions during play-fighting are most common among adolescent males, while adults are probably more heterosexually oriented. Male Whiptail Wallabies that court or mount other males also interact sexually with females, i.e., they are simultaneously bisexual.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Female Red-necked Wallabies are often harassed by males trying to mate with them (similar behavior also occurs in Whiptail Wallabies). As many as seven males at a time may pursue a single female, and they may injure her while mating: females have been seen limping or with cuts on their backs after heterosexual copulations. Mating attempts may also be interrupted by other males charging the pair and trying to dislodge the mounting male. In this species, only about 18 percent of the males ever mate with females. Nonbreeding females also occur in Eastern Gray Kangaroos. In addition, females who are pregnant (including late-term), not in heat, or sexually immature also occasionally participate in heterosexual activity, and males also regularly masturbate by thrusting the erect penis into the paws. DELAYED IMPLANTATION is another notable feature of the reproductive cycle in these species.

Other Species

Homosexual mounting occurs in a number of other Kangaroo and Wallaby species: between females in Yellow-footed Rock Wallabies (Petrogale xanthopus), and between males in Western Gray Kangaroos (Macropus fuliginosus), Red Kangaroos (Macropus rufus), Agile Wallabies (Macropus agilis), Black-footed Rock Wallabies (Petrogale lateralis), and Swamp Wallabies (Wallabia bicolor). Transgendered or intersexual individuals of various types are also found in several species, including Red Kangaroos, Euros (Macropus robustus), Tammar Wallabies (Macropus eugenii), and Quokkas (Setonix brachyurus). Some of these individuals have female body proportions and external genitalia, female or combined male-female internal reproductive organs, a scrotum, and absence of a pouch and mammary glands. Others have male reproductive organs, intermediate or female body proportions, and a pouch and mammary glands.

{452}

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

Coulson, G. (1997) "Repertoires of Social Behavior in Captive and Free-Ranging Gray Kangaroos, Macropus giganteus and Macropus fuliginosus (Marsupialia: Macropodidae)." Journal of Zoology, London 242:119-30.

* --- (1989) "Repertoires of Social Behavior in the Macropodoidea." In G. C. Grigg, P. J. Jarman, and I. D. Hume, eds., Kangaroos, Wallabies, and Rat-Kangaroos, pp. 457-73. Chipping Norton, NSW: Surrey Beatty and Sons.

* Grant, T. R., (1974) "Observations of Enclosed and Free-Ranging Gray Kangaroos Macropus giganteus." Zeitschrift fur Saugetierkunde 39:65-78.

* --- (1973) "Dominance and Association Among Members of a Captive and a Free-Ranging Group of Gray Kangaroos (Macropus giganteus)." Animal Behavior 21:449-56.

Jarman, P. J., and C. J. Southwell (1986) "Grouping, Association, and Reproductive Strategies in Eastern Gray Kangaroos." In D. I. Rubenstein and R. W. Wrangham, eds., Ecological Aspects of Social Evolution, pp. 399-428. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Johnson, C. N. (1989) "Social Interactions and Reproductive Tactics in Red-necked Wallabies (Macropus rufogriseus banksianus)." Journal of Zoology, London 217:267-80.

Kaufmann, J. H. (1975) "Field Observations of the Social Behavior of the Eastern Gray Kangaroo, Macropus giganteus" Animal Behavior 23:214-21.

* --- (1974) "Social Ethology of the Whiptail Wallaby, Macropus parryi, in Northeastern New South Wales." Animal Behavior 22:281-369.

* LaFollette, R. M. (1971) "Agonistic Behavior and Dominance in Confined Wallabies, Wallabia rufogrisea frutica." Animal Behavior 19:93-101.

Poole, W. E. (1982) "Macropus giganteus Shaw 1790, Eastern Gray Kangaroo." Mammalian Species 187:1-8.

--- (1973) "A Study of Breeding in Gray Kangaroos, Macropus giganteus Shaw and M. fuliginosus (Desmarest), in Central New South Wales." Australian Journal of Zoology 21:183-212.

Poole, W. E., and P. C. Catling (1974) "Reproduction in the Two Species of Gray Kangaroos, Macropus giganteus Shaw and M. fuliginosus (Desmarest). I. Sexual Maturity and Oestrus." Australian Journal of Zoology 22:277-302.

* Sharman, G. B., R. L. Hughes, and D. W. Cooper (1990) "The Chromosomal Basis of Sex Differentiation in Marsupials." Australian Journal of Zoology 37:451-66.

* Stirrat, S. C., and M. Fuller (1997) "The Repertoire of Social Behaviors of Agile Wallabies, Macropus agilis." Australian Mammalogy 20:71-78.

* Watson, D. M., and D. B. Croft (1993) "Playfighting in Captive Red-Necked Wallabies, Macropus rufogriseus banksianus." Behavior 126:219-245.

{453}

Tree and Rat Kangaroos

Tree and Rat Kangaroos

RUFOUS BETTONG (Aepyprymnus rufescens)

IDENTIFICATION: A small (6-7 pound), rodentlike kangaroo with reddish brown fur. DISTRIBUTION: Eastern and southern Australia. HABITAT: Grassy woodlands. STUDY AREAS: National Parks and Wildlife Service Center, Townsville, Australia; Zoological Garden of West Berlin, Germany.

DORIA'S KANGAROO (Dendrolagus dorianus)

MATSCHIE'S TREE KANGAROO (Dendrolagus matschiei)

IDENTIFICATION: Stocky, tree-dwelling kangaroos; chestnut or chocolate brown fur with lighter patches. DISTRIBUTION: Interior New Guinea; Doria's is vulnerable, Matschie's is endangered. HABITAT: Mountainous rain forests. STUDY AREAS: Karlsruhe Zoo, Germany; Woodland Park Zoological Gardens, Seattle, Washington.

Social Organization

Tree Kangaroos and Rufous Bettongs are largely solitary, although they sometimes associate in pairs, trios, or small groups of adults and young. About 15 percent of Bettong groups are same-sex. The mating systems of these species, though poorly understood, may involve polygamy or promiscuity, perhaps combined with monogamous pair-bonding in some populations of Rufous Bettongs. Males do not generally participate in raising their own offspring.

Description

Behavioral Expression: Female Rufous Bettongs sometimes court and mount other females, using behavior patterns also found in opposite-sex contexts. A homosexual interaction begins with one female approaching another and then sniffing and nuzzling her genital and pouch openings as well as her anus. The courting female becomes sexually aroused and exhibits a sinuous TAIL-LASHING, in which she moves her tail rapidly from side to side. The other female may initially react with hostility (as do females in heterosexual courtships), lying on her side and kicking with her hind feet while softly growling. As a result, the courting female might perform FOOT-DRUMMING, in which she stands upright on her hind legs near the other female and stamps one foot on the ground in front of her. If the other female {454}

calms down, the courting female may mount her by clasping her waist from behind and thrusting against her. Some homosexual interactions in Rufous Bettongs involve adult females courting and mounting juvenile females and vice versa. Sometimes males in the vicinity try to intervene or disrupt females engaging in homosexual behavior, but in other cases they simply ignore the activity. Mountings between females, including pelvic thrusting, also occur in Doria's and Matschie's Tree Kangaroos.

Frequency: Homosexual interactions occur fairly frequently in captive Rufous Bettongs: in one study, 3 out of 8 mounts were between females, and homosexual activity was observed a total of 19 times over one month. In Tree Kangaroos same-sex mounting occurs only occasionally.

Orientation: Female Rufous Bettongs that participate in homosexual behavior are probably bisexual, since most mate with males and become successful mothers. Most female Tree Kangaroos that mount other females probably also participate in heterosexual activity, although at least one Matschie's Tree Kangaroo that participated in same-sex mounts was a nonbreeder.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Heterosexual interactions in Rufous Bettongs have a number of nonprocreative aspects. For example, adult males generally make more sexual approaches to juvenile females than to sexually mature adult females. Nonreproductive REVERSE mounts — in which females mount males — occasionally occur in this species, as do attempted mounts by males on females who are not in heat. In the latter case, the female typically responds aggressively, vigorously kicking and growling at him. Although most heterosexual interactions occur between pairs of animals, sometimes two female Rufous Bettongs consort simultaneously with the same male as part of a trio. Among Matschie's Tree Kangaroos, a form of infanticide known as POUCH-ROBBING has occasionally been observed in captivity, in which females are severely aggressive toward other infants and may actually pull joeys from their mother's pouch and kill them.

Other Species

Female Tasmanian Rat Kangaroos (Bettongia gaimardi) also engage in homosexual mounting.

Sources (* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

* Coulson, G. (1989) "Repertoires of Social Behavior in the Macropodoidea." In G. C. Grigg, P. J. Jarman, and I. D. Hume, eds., Kangaroos, Wallabies, and Rat-Kangaroos, pp. 457-73. Chipping Norton, NSW: Surrey Beatty and Sons.

Dabek, L. (1994) "Reproductive Biology and Behavior of Captive Female Matschie's Tree Kangaroos, Dendrolagus matschiei." Ph.D. thesis, University of Washington.

Frederick, H., and C. N. Johnson (1996) "Social Organization in the Rufous Bettong, Aepyprymnus rufescens." Australian Journal of Zoology 44:9-17.

Ganslosser, U. (1993) "Stages in Formation of Social Relationships — an Experimental Investigation in Kangaroos (Macropodoidea: Mammalia)." Ethology 94:221-47. {455}

* --- (1979) "Soziale Kommunikation, Gruppenleben, Spiel- und Jugendverhalten des Doria-Baumkanguruhs (Dendrolagus dorianus Ramsay, 1833) [Social Communication, Group Life, and Play Behavior of Doria's Tree Kangaroo]." Zeitschrift fur Saugetierkunde 44:137-53.

* Ganslosser, U., and C. Fuchs (1988) "Some Quantitative Data on Social Behavior of Rufous Rat-Kangaroos (Aepyprymnus rufescens Gray, 1837 (Mammalia: Potoroidae)) in Captivity." Zoologischer Anzeiger 220:300-312.

George, G. G. (1977) "Up a Tree with Kangaroos." Animal Kingdom 80(2):20-24.

* Hutchins, M., G. M. Smith, D. C. Mead, S. Elbin, and J. Steenberg (1991) "Social Behavior of Matschie's Tree Kangaroo (Dendrolagus matschiei) and Its Implications for Captive Management." Zoo Biology 10:147-64.

Jarman, P. J. (1991) "Social Behavior and Organization in the Macropodoidea." Advances in the Study of Behavior 20:1-50.

* Johnson, P. M. (1980) "Observations of the Behavior of the Rufous Rat-Kangaroo, Aepyprymnus rufescens (Gray), in Captivity." Australian Wildlife Research 7:347-57.

Other Marsupials

Other Marsupials

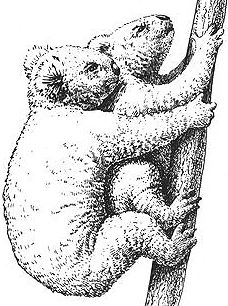

KOALA (Phascolarctos cinereus)

IDENTIFICATION: A bearlike marsupial with woolly brown or gray fur, large black nose, white chest, and long claws. DISTRIBUTION: Eastern and southeastern Australia. HABITAT: Eucalyptus forests. STUDY AREAS: Lone Pine Sanctuary, Brisbane, Australia; San Diego Zoo; subspecies

P.c. adustus.

Social Organization

Koalas are largely nocturnal and solitary, although in some populations they tend to live in scattered clusters of two to six females with several males. The mating system is probably promiscuous or polygamous (animals mate with multiple partners), and males take no part in raising their young.

Description

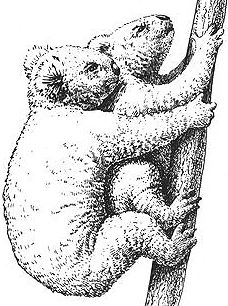

Behavioral Expression: Female Koalas in heat sometimes mount each other in the trees: while one female clings vertically to the trunk, another climbs behind her and reaches around to simultaneously hold on to the tree. She begins to make {456}

pelvic thrusts against the other female, while also typically gripping the other female's neck in her teeth (as does the male during heterosexual mounting). Occasionally one female mounts another from the side (a position sometimes also used by younger males). Usually the mounted female does not display the receptive posture (which involves arching her back while throwing her head back), and homosexual mounts are generally briefer than heterosexual ones. Like male-female copulations, homosexual interactions sometimes involve aggression between the participants: one female may attack the other or pin her to the ground following a mounting. Sometimes two females take turns mounting each other, and homosexual mounting is often interspersed with other signs of intense sexual arousal, including chasing, bellowing, and jerking. BELLOWING is an extraordinary call (also made by males) that has been described as a combination of rasping, growling, wheezing, grunting, rumbling, and braying. It consists of a long series of in-drawn, snorelike breaths alternating with exhalated, belchlike sounds. JERKING is a display resembling the hiccups, in which the female simultaneously jerks her body upward and flicks her head backward repeatedly. Male Koalas also sometimes mount each other, and a few even perform the jerking display like females in heat.

A female Koala mounting another female

Frequency: In captivity, same-sex mounting accounts for 11 percent of all copulatory activity, with the majority of this being mounts between females.

Orientation: Koalas that participate in homosexual mounting are probably bisexual, since females that mount other females have also been observed mating with males.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Heterosexual relations in Koalas are marked by a striking amount of aggression and violence: more than two-thirds of fights are between males and females rather than between males. Females are sometimes "pestered" by males that persistently follow, touch, bite, or snap at them; if the female returns the bites, the encounter can escalate into a severe fight. Males have been known to brutally attack females — including pregnant and nursing mothers — knocking them from the trees and savagely mauling them. In fact, it is typical for males to nip females on the neck during mating, and for heterosexual copulations to end with the male attacking the female. {457}

Females also fight with males (though less violently), and aggressiveness toward males is considered to be a defining feature of estrus for female Koalas. Occasionally adults are also abusive toward babies: mothers sometimes bite their young, while males have been observed attacking infants that interrupt them during a mating with their mother. Many heterosexual interactions are nonprocreative, since males often try to mount females who are not in heat. Although the females typically rebuff their advances, in some cases the males are able to mount them, often thrusting against the female and ejaculating on her without any penetration. Females in heat also sometimes mount males (REVERSE mounts).

Many wild populations of Koalas have particularly high rates of female infertility (and significantly reduced reproductive rates) due to venereal disease. More than half of all females in some areas are infected with genital chlamydia, a bacteria that causes a number of reproductive tract diseases and, ultimately, sterility. This pathogen has apparently been present in Koala populations for a relatively long time, as records of the associated diseases date back to at least the 1890s. Although the exact mode of its transmission is not yet fully understood, two routes have been implicated: sexual and mother-to-young. The latter may be due to the infant Koala's habit of eating its mother's feces directly from her anus during weaning, since she produces a special form of excrement known as PAP especially for feeding her young (this practice is also found in a number of other marsupials).

Other Species

In another marsupial, the Common Brushtail Possum (Trichosurus vulpecula), intersexuality or hermaphroditism occasionally occurs: one individual, for example, had male body proportions, coloring, and genitals combined with mammary glands and a pouch.

Sources (* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

Brown, A. S., A. A. Girjes, M. F. Lavin, P. Timms, and J. B. Woolcock (1987) "Chlamydial Disease in Koalas." Australian Veterinary Journal 64:346-50.

* Gilmore, D. P. (1965) "Gynandromorphism in Trichosurus vulpecula." Australian Journal of Science 28:165.

Lee, A., and R. Martin (1988) The Koala: A Natural History. Kensington, Australia: New South Wales University Press.

Phillips, K. (1994) Koalas: Australia's Ancient Ones. New York: Macmillan.

* Sharman, G. B., R. L. Hughes, and D. W. Cooper (1990) "The Chromosomal Basis of Sex Differentiation in Marsupials." Australian Journal of Zoology 37:451-66.

Smith, M. (1980a) "Behavior of the Koala, Phascolarctos cinereus (Goldfuss) in Captivity. III. Vocalizations." Australian Wildlife Research 7:13-34.

* --- (1980b) "Behavior of the Koala, Phascolarctos cinereus (Goldfuss) in Captivity. V. Sexual Behavior." Australian Wildlife Research 7:41-51.

--- (1980c) "Behavior of the Koala, Phascolarctos cinereus (Goldfuss) in Captivity. VI. Aggression." Australian Wildlife Research 7:177-90.

--- (1979) "Behavior of the Koala, Phascolarctos cinereus (Goldfuss) in Captivity. I. Non-Social Behavior." Australian Wildlife Research 6:117-29.

* Thompson, V. D. (1987) "Parturition and Development in the Queensland Koala Phascolarctos cinereus adustus at San Diego Zoo." International Zoo Yearbook 26:217-22.

Weigler, B. J., A. A. Girjes, N. A. White, N. D. Kunst, F. N. Carrick, and M. F. Lavin (1988) "Aspects of the Epidemiology of Chlamydia psittaci Infection in a Population of Koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) in Southeastern Queensland, Australia." Journal of Wildlife Diseases 24:282-91.

{458}

Carnivorous Marsupials

Carnivorous Marsupials

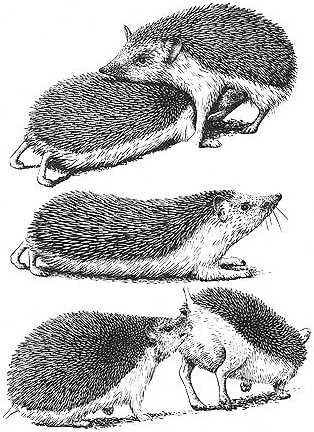

FAT-TAILED DUNNART (Sminthopsis crassicaudata)

IDENTIFICATION: A small, mouselike marsupial with a thick, conical, fat-storing tail. DISTRIBUTION: Inland southern Australia. HABITAT: Varied, including rocky areas. STUDY AREA: University of Adelaide, Australia.

NORTHERN QUOLL (Dasyurus hallucatus)

IDENTIFICATION: A catlike marsupial, up to 2 feet long, with grayish brown fur and white splotches. DISTRIBUTION: Northern and eastern Australia. HABITAT: Woodland, rocky areas. STUDY AREA: Monash University, Australia.

Social Organization

Fat-tailed Dunnarts often live together in small groups or pairs that share nests; these groupings are temporary and may consist of individuals of the same sex (especially outside of the breeding season). Although little is known about the social system of Northern Quolls, it appears that most individuals are largely solitary. Both species are nocturnal.

Description

Behavioral Expression: Homosexual mounting occurs among female, and to a lesser extent male, Northern Quolls. One animal climbs on top of another as in a heterosexual mating, grasping its chest with its front paws, and sometimes even riding on the back of the mounted animal as it walks around. In Fat-tailed Dunnarts, females in heat sometimes mount other females.

Frequency: In captivity, homosexual mounting among Northern Quolls occurs in almost two-thirds of encounters between females and 10 percent of encounters between males, though this may not reflect the frequency of its occurrence in the wild. Same-sex mounting only happens occasionally in female Fat-tailed Dunnarts.

Orientation: It is possible that some individuals in these species engage exclusively in same-sex behavior, while others may be bisexual, but little is known about {459}

the life histories of specific individuals. In one study, none of the Northern Quolls that participated in homosexual behavior engaged in heterosexual mounting (although observations were not made during the breeding season), while one female Fat-tailed Dunnart that mounted another female did not breed during a nearly yearlong study.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Reproduction in Northern Quolls is characterized by an extraordinary phenomenon sometimes known as MALE DIE-OFF. In many areas, virtually the entire male population perishes following the breeding season, while females typically survive to breed for another couple of seasons (some variation occurs between geographic locations and years in the proportion of males and females surviving). This complete annihilation of males is also a feature of a number of other carnivorous marsupial social systems and is found to a much lesser extent in Fat-tailed Dunnarts. Although the exact mechanism responsible for male mortality is not fully understood, it is thought to result from a number of stress-induced factors, perhaps directly related to participation in procreation. There is some evidence that nonbreeding males with lower testosterone levels — essentially "lower-ranking" males — have a higher survival rate than males that reproduce. Female Northern Quolls also routinely practice "abortion" or elimination of unborn young. As many as 17 embryos may begin developing in the female's uterus, but because females typically have no more than 8 nipples in their pouch, most of the embryos and/or newborn young will not survive. In Fat-tailed Dunnarts, breeding females can be noticeably aggressive toward males, attacking them when they attempt to mount; in captivity, females have even been known to kill their mates. In this species, heterosexual copulation can be a remarkably long affair, with the male remaining mounted on the female for hours at a time (sometimes as long as 11 hours); the female may struggle and attempt to escape during such arduous matings. In Northern Quolls, females often have neck and chest wounds inflicted by the male during mating. Adult male Fat-tailed Dunnarts sometimes display sexual interest in juvenile females, and incestuous matings have also been recorded. In addition, females in heat occasionally mount males (REVERSE mountings).

Other Species

Male Stuart's Marsupial Mice (Antechinus stuartii) mount individuals of both sexes during the mating period. Transgendered (intersexual) Tasmanian Devils (Sarcophilus harrisii) have also been reported: one individual had female genitalia and internal reproductive organs, combined with a scrotum and a pouch with mammary glands on only one side.

Sources (* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

Begg, R. J. (1981) "The Small Mammals of Little Nourlangie Rock, N.T. III. Ecology of Dasyurus hallucatus, the Northern Quoll (Marsupialia: Dasyuridae)." Australian Wildlife Research 8:73-85.

Croft, D. B. (1982) "Communication in the Dasyuridae (Marsupialia): A Review." In M. Archer, ed., Carnivorous Marsupials, vol. 1, pp. 291-309. Chipping Norton, Australia: Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales. {460}

* Dempster, E. R. (1995) "The Social Behavior of Captive Northern Quolls, Dasyurus hallucatus." Australian Mammalogy 18:27-34.

Dickman, C. R., and R. W. Braithwaite (1992) "Postmating Mortality of Males in the Dasyurid Marsupials, Dasyurus and Parantechinus." Journal of Mammalogy 73:143-47.

* Ewer, R. F. (1968) "A Preliminary Survey of the Behavior in Captivity of the Dasyurid Marsupial, Sminthopsis crassicaudata (Gold)." Zeitschrift fur Tierpsychologie 25:319-65.