<<< >>>

{528}

Shore Birds

SANDPIPERS AND THEIR RELATIVES

"Arctic" Sandpipers

"Arctic" Sandpipers

RUFF (Philomachus pugnax)

IDENTIFICATION: A large (12 inch) sandpiper with gray or brownish plumage and, in some males, spectacular ruffs and feather tufts on the head that vary widely in color and pattern (see below). DISTRIBUTION: Northern Europe and Asia; winters in Mediterranean, sub-Saharan Africa, Middle East, India. HABITAT: Tundra, lakes, swampy meadows, farms, floodlands. STUDY AREAS: Texel, Schiermonnikoog, Roderwolde, and several other locations in the Netherlands; Oie and Kirr Islands, Germany.

BUFF-BREASTED SANDPIPER (Tryngites subruficollis)

IDENTIFICATION: A medium-sized (7-8 inch) wading bird with a small head and short beak, buff-colored face and underparts, and regular dark brown patterning on the back and crown. DISTRIBUTION: Arctic Canada, Alaska, extreme northeast Siberia; winters in south-central South America. HABITAT: Tundra, grass-lands, mudflats. STUDY AREA: Meade River, Alaska.

Social Organization

Ruffs and Buff-breasted Sandpipers are both LEKKING species, which means that males gather together to perform elaborate courtship displays on communal grounds known as LEKS (some Buff-breasts also display solitarily). The mating system is polygamous or promiscuous: males (and sometimes females) mate with multiple partners, and females raise any resulting offspring on their own. Outside {529}

of the breeding season these sandpipers tend to associate in flocks, which can number in the thousands among Ruffs.

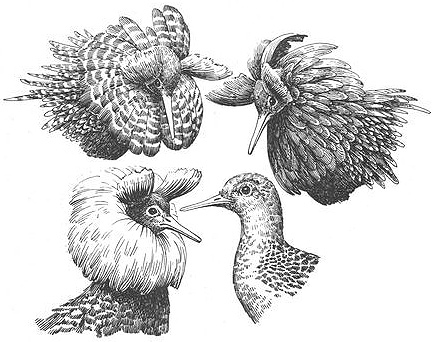

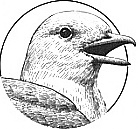

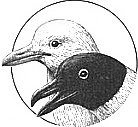

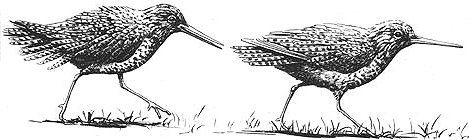

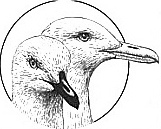

Four classes of male Ruffs, which differ in their physical appearance, social and sexual behavior, and genetics. Clockwise from upper left: resident, marginal, naked-nape, and satellite males.

Description

Behavioral Expression: There are four distinct types or "classes" of male Ruffs, differing in their appearance, social behavior, and sexuality. RESIDENT males generally have dark plumage (with a wide variety of different feather patterns) and defend their own territories on the lek. MARGINAL males look similar to residents but do not have their own territories; they stay on the periphery of the lek and are often attacked by residents. SATELLITE males usually have white or light-colored plumage; they do not own territories, but often visit the lek and associate with particular residents. Finally, NAKED-NAPE males lack the nuptial plumage — ruff and head tufts — of other males, giving them the superficial appearance of females. They are not territorial either, but occasionally visit leks for short periods. Naked-napes may include younger males and/or adults passing through on their migratory journeys prior to developing their breeding plumage. Resident and satellite males also differ genetically from one another.

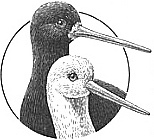

Homosexual behavior occurs among males of all types and is especially prominent between residents and satellites. While a resident male is displaying on his territory, one or more satellites may approach him and engage in courtship behaviors. Most notable of these is SQUATTING, in which the males lie with their bellies to the ground and expand their ruffs, crouching together while the resident places his bill on top of the satellite's head. This may lead to homosexual copulation, in which either the resident or the satellite mounts the other male and attempts to make genital contact — he lowers himself and spreads his wings while holding the other male's head feathers in his bill. The mounted bird reacts by either remaining crouched or by trying to shake the other male off his back. If more than one satellite male is present on the lek, they sometimes also mount each other. Many satellites have "preferred" resident males with whom they spend most of their time, and residents may also actively entice satellite males onto their display courts.

Females are often drawn to the activities between resident and satellite males, and heterosexual courtship and copulation (involving either residents or satellites) may occur at the same time as homosexual activities (or shortly thereafter). Occasionally, a satellite male will mount a resident male who is in the act of mating with a female; residents and satellites may also try to prevent each other from mating with females. Naked-nape males also engage in homosexual mounting with each other and with residents. When a naked-nape arrives on the lek, the resident male may respond by squatting; the naked-nape approaches him in a horizontal posture or may himself squat. The naked-nape may then try to mount the resident, although he does not usually lower his body to "complete" the copulation; he may also mount in a backwards position with his head facing the resident's tail. Residents also sometimes mount naked-napes, and naked-napes also mount each other. Naked-nape males are sometimes courted by other males during stopovers on the spring migration as well (i.e., outside of the mating season). Although {530}

marginal males rarely participate in sexual activity (with either males or females), they have occasionally been seen mounting other males.

Female Ruffs — also known as Reeves — engage in homosexual behavior as well. They often arrive on a lek in groups, and females sometimes mount one another as they begin simultaneously crouching near a resident male during courtship activities. Genital contact may occur, although this is difficult to verify, even for heterosexual (or male homosexual) copulations. Females also occasionally court each other, using some of the same stylized movements such as wing quivering that are seen in heterosexual courtship.

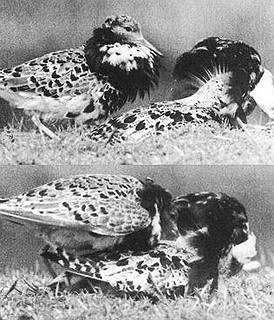

Male Buff-breasted Sandpipers attract other birds to their lek territories with a dramatic WING-UP DISPLAY that can be seen from miles away, in which they raise one wing vertically and flash its brilliant satiny-white underlining. Usually females are attracted to this courtship display, and sometimes up to six of them gather around a displaying male. Often, however, a male from a neighboring territory is drawn to the display as well (or he may "camouflage" himself in a group of females). He may interrupt the courtship when he arrives by mounting the displaying male and trying to copulate with him. He may also aggressively peck the other male on his head and neck while mounted on him, then fly back to his own territory. Sometimes the females follow him, and then the pattern of interruption and mounting is repeated, only this time the other male arrives to disrupt the courtship. This sequence of heterosexual courtship and homosexual mounting may be repeated many times, back and forth for an hour or more. Sometimes, instead of flying back to his own territory with the females, a male simply returns repeatedly to his neighbor's territory, continuously interrupting the male's courtship by mounting him. Homosexual mounting also occurs in other contexts: when not as many females are present on the leks (especially later in the mating season), one or more males may enter a neighbor's territory and simply mount him. As many as four males at a time may participate in such activity.

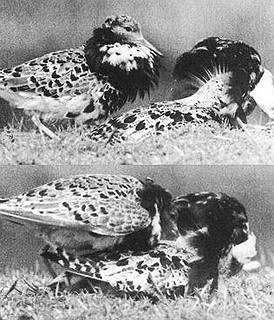

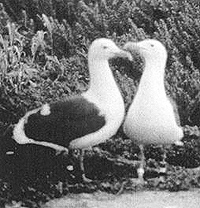

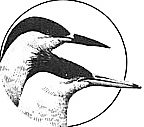

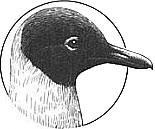

A "marginal" male Ruff approaches a crouching "satellite" male (above) and then mounts him

Frequency: Homosexual mounting occurs regularly in Ruffs, especially at the beginning of the mating season. During one informal three-and-a-half-hour {531}

observation period, for example, 3 out of 12 mountings (25 percent) were between males. In Buff-breasted Sandpipers, courtship interruptions by other males are common. Nearly a third of all courtships are disrupted by another male's arrival, although homosexual mounting does not necessarily take place every time — but then neither does heterosexual mounting, since females usually leave without having copulated (even if there has been no interruption).

Orientation: In Ruffs, homosexual behavior is seen primarily in resident males, who constitute about 40 percent of the male population, and satellite males, who make up roughly 15 percent to one-third of all males (on average). Not all of these individuals engage in same-sex mounting — but neither do they all participate in heterosexual mounting. On some leks, just over half the resident males mate with females — and some only copulate once each season — while 40-90 percent of satellites never mate with females (although they may court them). Of those birds that do participate in homosexual behavior, many alternate between same-sex and opposite-sex interactions and are therefore bisexual. This is also true of females, although some Reeves seem to "prefer" homosexual interactions since they ignore males in favor of mounting other females. Naked-nape males — who probably constitute no more than 10 percent of the male population — rarely, if ever, mate with females. Thus, when naked-napes and nonmating residents and satellites are all taken into account, significant portions of the male Ruff population — perhaps more than half — are involved predominantly, if not exclusively, in sexual activity with other males. This homosexuality may be long-term — satellites, for example, almost never become residents during their entire lives (since these two classes differ genetically). Most male Buff-breasted Sandpipers that mount other males are probably functionally bisexual (if not predominantly heterosexual), since they also court and mate with females.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Birds who do not mate or breed are a notable feature of both Ruff and Buff-breasted Sandpiper populations (as noted above). More than 60 percent of male Ruffs, on average, do not copulate with females (this includes males of all categories), while more than half of all territorial Buff-breasted males do not mate (and many males in this species are not territorial and hence probably do not reproduce either). In many cases, males are unable to breed because females select which males they want to mate with and often refuse to allow certain males to copulate with them. However, females of both species occasionally choose more than one male to mate with: almost a quarter of all Buff-breasted nests contain eggs fathered by more than one male, while Reeves have been known to copulate with several different males in a row. Sometimes, more than one male will even try to copulate simultaneously with the same female — usually a resident and a satellite together. Cross-species sexual activity has also been observed: male Ruffs occasionally court and try to mount other sandpipers such as red knots (Calidris canutus).

Courtship and mating are virtually the only times during the entire breeding season when the two sexes are together: in both species, there is significant separation {532}

(both physical and temporal) between males and females. After copulating, female Ruffs often leave the lek and migrate farther north to lay their eggs — sometimes more than 1,800 miles away, and two to three weeks after they last mated. It is thought that females are able to do this because they store sperm in special glands in their reproductive tracts, effectively separating fertilization from insemination. Male Buff-breasts take no part in parenting, and in fact depart from the leks well before the eggs hatch. Male Ruffs also generally leave parenting entirely to the females, who occasionally cooperate amongst themselves in tending and defending their young. In fact, chicks may be killed by males if the two sexes ever interact following the hatching of eggs. Infanticide has not been observed in Buff-breasts, although about 10 percent of nests are abandoned by females if a predator takes some of the eggs. Sex segregation also occurs in Ruffs after the breeding season because males and females have different migratory patterns. Females tend to travel farther south to spend the winter, and at some wintering sites in Africa they may outnumber males 15 to 1.

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

Cant, R. G. H. (1961) "Ruff Displaying to Knot." British Birds 54:205.

* Cramp, S., and K. E. L. Simmons (eds.) (1983) "Ruff (Philomachus pugnax)." In Handbook of the Birds of Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa, vol. 3, pp. 385-402. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

* Hogan-Warburg, A.J. (1993) "Female Choice and the Evolution of Mating Strategies in the Ruff Philomachus pugnax (L.)." Ardea 80:395-403.

* --- (1966) "Social Behavior of the Ruff, Philomachus pugnax (L.)." Ardea 54:109-229.

Hugie, D. M., and D. B. Lank (1997) "The Resident's Dilemma: A Female Choice Model for the Evolution of Alternative Mating Strategies in Lekking Male Ruffs (Philomachus pugnax)." Behavioral Ecology 8:218-25.

* Lanctot, R. B. (1995) "A Closer Look: Buff-breasted Sandpiper." Birding 27:384-90.

* Lanctot, R. B., and C. D. Laredo (1994) "Buff-breasted Sandpiper (Tryngites subruficollis)." In A. Poole and F. Gill, eds., The Birds of North America: Life Histories for the 21 st Century, no. 91. Philadelphia: Academy of Natural Sciences; Washington, D.C.: American Ornithologists' Union.

Lank, D. B., C. M. Smith, O. Hanotte, T. Burke, and F. Cooke (1995) "Genetic Polymorphism for Alternative Mating Behavior in Lekking Male Ruff Philomachus pugnax." Nature 378:59-62.

* Myers, J. P. (1989) "Making Sense of Sexual Nonsense." Audubon 91:40-45.

--- (1980) "Territoriality and Flocking by Buff-breasted Sandpipers: Variations in Non-breeding Dispersion." Condor 82:241-50.

--- (1979) "Leks, Sex, and Buff-breasted Sandpipers." American Birds 33:823-25.

Oring, L. W. (1964) "Displays of the Buff-breasted Sandpiper at Norman, Oklahoma." Auk 81:83-86.

Pitelka, F. A., R. T. Holmes, and S. F. MacLean, Jr. (1974) "Ecology and Evolution of Social Organization in Arctic Sandpipers." American Zoologist 14:185-204.

Prevett, J. P., and J. F. Barr (1976) "Lek Behavior of the Buff-breasted Sandpiper." Wilson Bulletin 88:500-503.

Pruett-Jones, S. G. (1988) "Lekking versus Solitary Display: Temporal Variations in Dispersion in the Buff-breasted Sandpiper." Animal Behavior 36:1740-52.

* Scheufler, H., and A. Stiefel (1985) Der Kampflaufer [The Ruff]. Neue Brehm-Bucherei, 574. Wittenberg Lutherstadt: A. Ziemsen Verlag.

* Selous, E. (1906-7) "Observations Tending to Throw Light on the Question of Sexual Selection in Birds, Including a Day-to-Day Diary on the Breeding Habits of the Ruff (Machetes pugnax)." Zoologist 10:201-19, 285-94, 419-28; 11:60-6, 161-82, 367-80.

* Stonor, C. R. (1937) "On a Case of a Male Ruff (Philomachus pugnax) in the Plumage of an Adult Female." Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, Series A 107:85-88.

* van Rhijn, J. G. (1991) The Ruff: Individuality in a Gregarious Wading Bird. London: T. and A. D. Poyser.

--- (1983) "On the Maintenance and Origin of Alternative Strategies in the Ruff Philomachus pugnax." Ibis 125:482-98.

--- (1973) "Behavioral Dimorphism in Male Ruffs, Philomachus pugnax (L.)." Behavior 47:153-229.

{533}

Shanks

Shanks

(Common) GREENSHANK (Tringa nebularia)

IDENTIFICATION: A large (13-14 inch) sandpiper with streaked and spotted, dark brownish gray plumage; long and slightly upturned bill; greenish yellow legs. DISTRIBUTION: North-central Europe and Asia; winters in western Europe, Africa, Australasia. HABITAT: Marshes, bogs, moors, lakes. STUDY AREAS: Speyside and the northwest highlands of Scotland.

(Common) REDSHANK (Tringa totanus)

IDENTIFICATION: Slightly smaller than the Greenshank; plumage grayish brown, with black and dark brown streaks and spots; orange-red legs. DISTRIBUTION: Europe and central Asia; winters in coastal Africa, Middle East, southern Asia. HABITAT: Wet meadows, moors, marshes, lakes, rivers. STUDY AREA: Ribble Marshes National Nature Reserve, Lancashire, England; subspecies

T.t. totanus.

Social Organization

Outside of the mating season, Greenshanks congregate in flocks of 20-25 birds, while Redshanks are less social and may even be solitary. During the mating season, monogamous pairs are the predominant social unit, although a number of variations occur, including nonbreeding birds (see below).

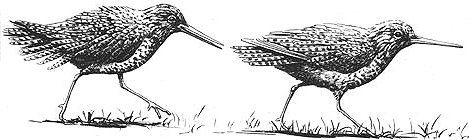

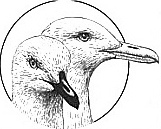

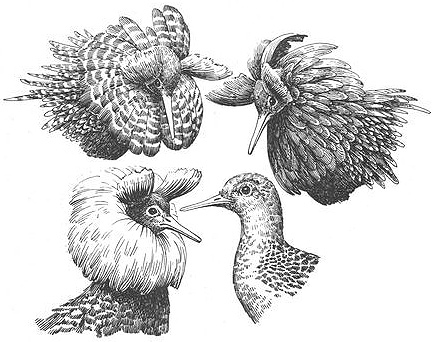

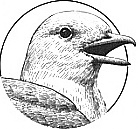

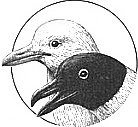

Homosexual courtship in Redshanks: one male pursuing another in a "ground chase"

Description

Behavioral Expression: In both Greenshanks and Redshanks, males sometimes court and copulate with each other. Homosexual courtship in Greenshanks involves spectacular aerial and ground displays, employing patterns also found in heterosexual courtship. One male may pursue another in a NUPTIAL FLIGHT, which starts out as a twisting, careening chase low over the ground, followed by a remarkable ascent of both birds to a great altitude. The two males swerve and turn in unison as they climb higher, sometimes disappearing completely into the clouds; the "sky dance" comes to a dramatic close as the males plummet back to earth in a steep dive. In the ground courtship display, two males bow, fan their tails, flap their wings, and utter deep growling calls or chip, quip, and too-hoo notes. This may lead {534}

to copulation (often performed on a stump or tree branch), in which one male flutters onto the back of another, lowering his body to make contact with the other while slowly flapping his wings. Homosexual copulation may be briefer than the corresponding heterosexual behavior. Males also sometimes try to copulate with other males that are calling in the treetops, and with males whose female mates are incubating eggs (in the latter cases, the female often makes a threatening or challenging call during the homosexual interaction). Male Greenshanks are also sometimes courted by male Green Sandpipers (Tringa ochropus), who approach them from behind with drooping wings and raised, partially fanned tails. The Sandpipers may also try to mount them; in contrast to within-species homosexual matings, male Greenshanks typically resist these sexual advances, shaking the Sandpipers off and violently pecking at them.

Male Redshanks court other males with a GROUND CHASE (also used in heterosexual courtship). In this display, one male pursues another in a series of curves and circles, often running in a distinctive sideways motion — similar to that of a crab — with ruffled feathers and fanned tail. The pursuing male may give a "mate-call" consisting of repeated paired notes: tyoo-tyoo ... tyoo-tyoo ... , and both birds also sometimes make chipping or trilled calls during the chase. Occasionally one male also mounts the other and tries to copulate with him, although his advances are often rebuked by the other male (as also frequently happens in heterosexual copulations).

Frequency: Homosexual courtship and copulation probably occur only occasionally in Greenshanks and Redshanks, although no systematic long-term studies of their prevalence have yet been undertaken.

Orientation: In many cases, individuals that engage in same-sex activity are bisexual. Male Greenshanks and Redshanks court birds of both sexes, while male Greenshanks are sometimes heterosexually paired fathers when they participate in homosexual copulations with other males. In at least one case, a male Greenshank associated himself with a heterosexual pair and tried to copulate with both the male and the female (although it is not known whether that male himself was single or paired with a female).

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Sexual behavior in these two Sandpipers often occurs at times when fertilization is not possible: male Greenshanks and Redshanks court and mate with {535}

females after eggs are laid, both during incubation and following the hatching of chicks. In addition, REVERSE mounting (in which the female mounts the male) also occurs in Greenshanks. Courtship and copulation with other species of sandpipers have been recorded, including lesser yellowlegs (Tringa flavipes) and Green Sandpipers (as noted above). A wide variety of alternative heterosexual mating and parenting arrangements are also found in these birds. Although both Greenshanks and Redshanks are primarily monogamous, males of both species sometimes court and mate with females other than their own mate. In addition, some individuals engage in a number of different polygamous mating arrangements: occasional trios occur in both species, composed of two females and a male. Both females may lay in the same nest, they may have separate nests, or one female may be nonbreeding. Redshanks sometimes also participate in serial polygamy, in which a male mates with a second female, or a female with a second male, after laying a clutch with a first mate. This involves deserting or "divorcing" the first mate, who then typically raises the young as a single parent. (In Greenshanks, another form of "single parenting" occasionally occurs, in which the male partner fails to help the female incubate the eggs, but remains paired with her.) In fact, about 11 percent of Redshanks (and up to a quarter of Greenshanks) change partners between or within breeding seasons (this is more common among males), and only about a third of all males and half of all females mate for life. Some birds may divorce and re-pair with up to four different partners during their lives. In a few cases, female Redshanks have even left their mate to pair with another male, only to return to their "ex" the following season and remain with him for many more years. Adoption or foster-parenting also takes place in Redshanks: females sometimes lay eggs in other females' nests (who then raise all the chicks as their own), and Redshanks have even been seen taking care of chicks of other species of shorebirds, such as the avocet (Recurvirostra avosetta).

Some Greenshanks do not participate in breeding at all — about a quarter of all males, on average, do not procreate (and in some years this figure may be higher — nearly half of all males). This includes both single birds and those that are heterosexually paired but do not breed. Such nonbreeding pairs constitute an average of more than 15 percent of pairs, though in some years more than a third do not reproduce. Heterosexual relations may also be marked by unwillingness and aggression between the sexes: female Redshanks sometimes turn on males that are chasing them during courtship, staving off their advances with prolonged fights involving much pecking and scratching. Females of both species may also refuse to allow males to mount them: about a third of all Redshank heterosexual mating attempts, for example, are not completed due to female refusal.

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

* Cramp, S., and K. E. L. Simmons (eds.) (1983) "Redshank (Tringa totanus)." In Handbook of the Birds of Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa, vol. 3, pp. 531-35. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Garner, M. S. (1987) "Lesser Yellowlegs Attempting to Mate with Redshank." British Birds 80:283.

Hakansson, G. (1978) "Incubating Redshank, Tringa totanus, Warming Young of Avocet, Avocetta recurvirostra." Var Fagelvarld 37:137-38.

* Hale, W. G. (1980) Waders. London: Collins. {536}

* Hale, W. G., and R. P. Ashcroft (1983) "Studies of the Courtship Behavior of the Redshank Tringa totanus." Ibis 125:3-23.

* --- (1982) "Pair Formation and Pair Maintenance in the Redshank Tringa totanus." Ibis 124:471-501.

* Nethersole-Thompson, D. (1975) Pine Crossbills: A Scottish Contribution. Berkhamsted: T. and A. D. Poyser.

* --- (1951) The Greenshank. London: Collins.

* Nethersole-Thompson, D., and M. Nethersole-Thompson (1986) Waders: Their Breeding, Haunts, and Watchers. Calton: T. and A. D. Poyser.

* --- (1979) Greenshanks. Vermillion, S.D.: Buteo Books.

Thompson, D. B. A., P. S. Thompson, and D. Nethersole-Thompson (1988) "Fidelity and Philopatry in Breeding Redshanks (Tringa totanus) and Greenshanks (T. nebularia)." In H. Ouellet, ed., Acta XIX Congressus Internationalis Ornithologici (Proceedings of the 19th International Ornithological Congress), 1986, Ottawa, vol. I, pp. 563-74. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press.

--- (1986) "Timing of Breeding and Breeding Performance in a Population of Greenshanks (Tringa nebularia)." Journal of Animal Ecology 55:181-99.

Stilts

Stilts

BLACK-WINGED STILT (Himantopus himantopus)

IDENTIFICATION: A fairly large (12-15 inch) sandpiper-like bird with long pink legs, white plumage with black wings and back, and a slender black bill. DISTRIBUTION: Throughout much of Australasia, Europe, Africa, Central and South America, western and southern United States. HABITAT: Tropical and temperate wetlands. STUDY AREAS: Gyotuku Sanctuary, Ichikawa City, Japan; Morocco and the Belgium/Netherlands border area; subspecies H.h. himantopus.

BLACK STILT (Himantopus novaezelandiae)

IDENTIFICATION: Similar to Black-winged Stilt but with entirely black plumage. DISTRIBUTION: New Zealand; critically endangered. HABITAT: Rivers, lakes, swamps. STUDY AREA: Mackenzie Basin, South Island, New Zealand.

Social Organization

The primary social unit among Stilts is the monogamous mated pair; Black-winged couples often nest in loose colonies containing 2-50 families, while Black {537}

Stilts are less gregarious. Outside of the mating season, the birds gather in flocks of usually up to ten individuals, although assemblies of hundreds of Black-winged Stilts may also occur.

A nest with a "supernormal clutch" of eggs belonging to a pair of female Black-winged Stilts in Japan

Description

Behavioral Expression: Lesbian pairs occur in both Black-winged and Black Stilts. In these partnerships, two females participate in courtship, copulation, and parenting activities together. Homosexual pairing and courtship in Black-winged Stilts often begins with a ritual NEST DISPLAY activity: each female takes turns symbolically "showing" the other a nest location by squatting on land as if she were incubating eggs, and making pecking motions in the mud as though she were turning the eggs over. Although heterosexual pairings also frequently commence with this activity, in lesbian pairs the two birds may spend considerably more time engaged in nest display. This may lead to full-scale courtship activities, such as DIBBLING — bill dipping and shaking by both partners, involving prominent splashing of water — and ritual preening, in which one female preens the side of her breast nearest to the other female, frequently combined with more splashing activity. Often one female takes up the NECK EXTENDED posture, a stylized pose in which she stands with her legs slightly apart and her neck lowered and extended just above the surface of the water. While one female is standing in this position, the other performs a courtship dance in which she moves back and forth behind her partner, striding in semicircles from one side to the other. The two females may participate in continuous courtship activities for up to three-quarters of an hour at a time. Sexual activity also takes place between members of a lesbian pair, with one female mounting the other as in heterosexual copulation.

Once bonded, the pair vigorously defends their territory against any intruding families and eventually builds a nest together. Because both females sometimes lay eggs, the nests of lesbian pairs often contain SUPERNORMAL CLUTCHES of 7-8 eggs, up to twice as many as those of heterosexual pairs (which usually have only 3-4 eggs). Both females take turns incubating the eggs; in heterosexual pairs the two birds also share incubation duties, but in many cases the female contributes a disproportionately greater amount of time than does the male. If the eggs are eaten by predators, the lesbian pair replaces them by laying a second clutch (as often happens with heterosexual parents as well). Most eggs laid by {538}

same-sex pairs are probably infertile. Like heterosexual pairs, some Black-winged Stilt lesbian pairs divorce. This may occur, for example, when one female forms a new pair-bond with another female. Although mate-switching may initially be accompanied by aggression between the separating females, the divorced partner sometimes still remains "friends" with the new pair, being allowed to visit their territory (unlike other birds, which are routinely chased away).

Frequency: In Black-winged Stilts, female pairs may constitute anywhere from 5-17 percent of the total number of pairs (depending on the population), while about 2 percent of Black Stilt pairings are lesbian. Homosexual copulation occurs at fairly high rates in some Black-winged Stilt female pairs: in one case, two females were seen to mate with each other as often as five times in one day.

Orientation: Because the eggs they lay are usually infertile, it is likely that many female Black-winged Stilts in lesbian pairs are exclusively homosexual, i.e., they do not copulate with males (at least for the duration of their bond). In addition, some females show a persistent orientation toward other females, since they remate with another female if their lesbian partnership breaks up.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

In addition to long-lasting monogamous pairs, a variety of alternative heterosexual family arrangements occur in Stilts. Black Stilts occasionally form trios of two females and one male (with both females laying eggs), while Black-winged Stilt pairs sometimes adopt chicks from other families and foster-parent them along with their own. Divorce and remating may occur in male-female pairs of Black-winged Stilts, and some males engage in courtship and copulation with females other than their mates. In Black Stilts, heterosexual pairs sometimes separate when their young fledge: the male often takes the juveniles with him as a single parent when he migrates, while the female remains behind. On returning, the male may get back together with his previous partner, or the female may find a new mate. In some intact Black Stilt families, fathers maybe abusive toward their young, behaving aggressively or rejecting their male offspring (although this has so far only been reported in captivity). In both of these Stilt species, individuals often masturbate by mounting an inanimate object (such as a piece of driftwood) and performing copulatory movements. In Black-winged Stilts this behavior may occur with extraordinary frequency — one bird was recorded making 20-30 such masturbatory mounts in one session, roughly once every 30 seconds. Finally, birds sometimes pair with individuals outside of their species: in some populations, about 30 percent of Black Stilts mate with Black-winged Stilts, and hybrids of the two species are common.

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

Cramp, S., and K. E. L. Simmons, eds. (1983) "Black-winged Stilt (Himantopus himantopus)." In Handbook of the Birds of Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa, vol. 3, pp. 36-47. Oxford: Oxford University Press. {539}

Goriup, P. D. (1982) "Behavior of Black-winged Stilts." British Birds 75:12-24.

Hamilton, R. B. (1975) Comparative Behavior of the American Avocet and the Black-necked Stilt (Recurvirostridae). Ornithological Monographs no. 17. Washington, DC: American Ornithologists' Union.

Kitagawa, T. (1989) "Ethosociological Studies of the Black-winged Stilt Himantopus himantopus himantopus. I. Ethogram of the Agonistic Behaviors." Journal of the Yamashina Institute of Ornithology 21:52-75.

* --- (1988a) "Ethosociological Studies of the Black-winged Stilt Himantopus himantopus himantopus. III. Female-Female Pairing." Japanese Journal of Ornithology 37:63-67.

--- (1988b) "Ethosociological Studies of the Black-winged Stilt Himantopus himantopus himantopus. II. Social Structure in an Overwintering Population." Japanese Journal of Ornithology 37:45-62.

* Pierce, R. J. (1996a) "Recurvirostridae (Stilts and Avocets)." In J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, and J. Sargatal, eds., Handbook of the Birds of the World, vol. 3: Hoatzin to Auks, pp. 332-47. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions.

--- (1996b) "Ecology and Management of the Black Stilt Himantopus novaezelandiae." Bird Conservation International 6:81-88.

(1986) Black Stilt. Endangered New Zealand Wildlife Series. Dunedin, New Zealand: John McIndoe and New Zealand Wildlife Service.

* Reed, C. E. M. (1993) "Black Stilt." In S. Marchant and P. J. Higgins, eds., Handbook of Australian, New Zealand, and Antarctic Birds, vol. 2, pp. 769-80. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Oystercatchers and Plovers

Oystercatchers and Plovers

(Eurasian) OYSTERCATCHER (Haematopus ostralegus)

IDENTIFICATION: A large (17 inch), stocky shore bird with black upperparts, white underparts, and red-orange bill, eyes, and legs. DISTRIBUTION: Throughout Eurasia; winters in Africa, Middle East, southern Asia. HABITAT: Beaches, salt marshes, rocky coasts, mudflats. STUDY AREAS: The islands of Texel, Vlieland, and Schiermonnikoog, the Netherlands; subspecies H.o. ostralegus.

(Eurasian) GOLDEN PLOVER (Pluvialis apricaria)

IDENTIFICATION: A medium-sized (10 inch) sandpiper-like bird with mottled buff and black plumage; adult males have a black face and underparts bordered with white. DISTRIBUTION: Northern Europe; winters south to Mediterranean and North Africa. HABITAT: Tundra, bogs, moors, heath. STUDY AREA: Dorback Moor, Scotland; subspecies

P.a. apricaria.

{540}

Social Organization

Oystercatchers and Golden Plovers commonly associate in flocks. The mating system typically involves monogamous pair-bonding, although many alternative arrangements also occur (see below). Nonbreeding Oystercatchers tend to aggregate in groups known as CLUBS.

Description

Behavioral Expression: Oystercatchers sometimes participate in same-sex courtship and copulation. This behavior typically occurs within bisexual trios, that is, an association of three birds — two of one sex and one of the other — in which all three members have a bonded sexual relationship. For example, two males and a female sometimes form a trio, and in addition to heterosexual activity between the opposite-sex partners, the two males may court and mount each other. Several different courtship and pair-bonding displays are used in both same-sex and opposite-sex contexts. For example, while walking around each other, two males might perform BALANCING, in which they make seesaw movements with their bodies, or the THICK-SET ATTITUDE, a stylized posture in which the head is drawn down between the shoulders with the tail and back horizontal, all the while bending the legs and making tripping steps. Sometimes two males also perform ritualized nest-building activities as part of their mutual courtship, such as THROWING STRAWS, in which they toss straw and other materials backward, or PRESSING A HOLE, in which they repeatedly sit down, pressing their breasts and wings against the ground as if fashioning a nest. As a prelude to copulation, one male approaches the other in the STEALTHY ATTITUDE, similar to the thick-set attitude except that the head is held to one side and the tail is pressed down and spread. One male may mount and try to copulate with the other, although sometimes his sexual advances are thwarted by an attack from the other male. Interestingly, all three members of such a trio may be nonmonogamous, engaging in heterosexual courtship or copulations with birds other than their primary partners.

Homosexual activities also occur between two female Oystercatchers that form part of a bisexual trio with a male. Most associations of this type start off the way heterosexual trios do, with considerable aggression between the females, but eventually they develop a strong bond with each other. They preen one another while remaining close together and also cooperate (along with their male partner) in mutual defense of their territory. Employing the same behavior patterns seen in heterosexual mating, the two females also regularly copulate with one another: one female approaches the other in a hunched posture, making soft pip-pip noises while her partner tosses her tail upward. Then, while mounting, the female flaps her wings to maintain balance and may push her tail under the other female's in order to achieve genital (cloacal) contact, at which point she utters soft wee-wee sounds. The two birds may take turns mounting one another, and about 47 percent of lesbian copulations include full genital contact (compared to 67 percent of matings by heterosexual pairs and 74 percent of male-female copulations in heterosexual trios). The females also mate regularly with their male partner, eventually building a joint nest together in which they each lay eggs. This results in a SUPERNORMAL CLUTCH {541}

of up to 7 eggs (compared to a maximum of 4-5 in nests of heterosexual pairs, or in each of the two separate nests of heterosexual trios). All three partners take turns incubating the eggs and they cooperate in raising their chicks. However, because each bird is usually unable to adequately cover all 7 eggs simultaneously, bisexual trios generally hatch and raise fewer offspring than do heterosexual pairs. Bisexual trios can remain together for up to 4-12 years, comparable to Oystercatcher heterosexual pairs, and are actually more stable and longer-lasting than heterosexual trios (which typically do not extend beyond 4 years).

Male Golden Plovers occasionally court and pair with each other in the early spring. Courtship activities often begin with ground displays, in which one male chases the other with his head lowered, wings half-spread, and back feathers ruffled, all the while raising and lowering his fanned tail. This may develop into a spectacular twisting aerial pursuit flight, in which the two males synchronously dip and climb, careening and skimming over the ground in a dramatic, high-speed chase that may take them far from their home territories.

Frequency: Homosexual behavior occurs occasionally in Oystercatcher and Golden Plover populations. Less than 2 percent of Oystercatchers, for example, live in trios of two females with one male, although 43 percent of such associations involve homosexual bonding and sexual activities. Overall, about 1 in every 185 copulations is between two females; lesbian matings take place roughly once every 6-7 hours within each bisexual trio, compared to roughly once every 3-6 hours for heterosexual matings (in a pair or trio). Likewise, approximately 1 out of every 400 Oystercatcher bonds involves a trio of two males with a female, and only some of these include same-sex activity. As in bisexual trios with two females, however, homosexual behavior may be fairly frequent within the association: in one such trio, for instance, almost two-thirds of all courtship activities were homosexual, and 15 — 19 percent of all mounting activities were same-sex.

Orientation: Oystercatchers that participate in same-sex activities are usually bisexual, being part of a bonded trio with a member of the opposite sex and sometimes also engaging in promiscuous heterosexual activities. Within the trio, however, one bird may be more homosexually oriented than the other, i.e., it may have a closer bond with a bird of the same sex, while the other may have a stronger heterosexual bond. In one bisexual trio involving two males and a female, for example, 85 percent of one male's courtship activities and more than a third of his mounting activities were homosexual; for the other male, about 70 percent of his courtships and a quarter of his mounting activities were same-sex. Some female Oystercatchers in bisexual trios also end up leaving their trio and pairing with a male, although this occurs less frequently than for females in heterosexual trios.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Polygamous heterosexual trios (without same-sex activities) sometimes form in Oystercatchers (as mentioned above), and the same phenomenon also occurs in Golden Plovers. In addition, several other variations on the long-term, monogamous, {542}

male-female parenting unit have developed in these species. Although pair-bonds in Oystercatchers and Golden Plovers sometimes last for life, heterosexual partners may divorce and re-pair with new mates. In some Oystercatcher populations 6-10 percent of couples divorce, and the average length of a pair-bond is only two to three years. Some birds (particularly females) divorce repeatedly and may have as many as six or seven different partners during their lives, and only about half of all birds remain with the same partner for life. A female Golden Plover sometimes deserts her mate during the breeding season (often to start a second family with a new male); her former mate must then raise their young on his own. In addition to single parenting, "double-family parenting" sometimes occurs: two Plover families occasionally share the same territory (with one couple breeding earlier than the other) and may help defend each other's brood. Oystercatcher pairs sometimes foster-parent chicks of other related species such as lapwings (Vanellus vanellus) and avocets (Recurvirostra avosetta), occasionally even "adopting" and hatching foreign eggs.

Infidelity is a prominent feature of Oystercatcher pair-bonds. Up to 7 percent of all copulations are nonmonogamous, often between a paired female and a single male (and usually initiated by the female). Females often have an extended "affair" with a particular male over several years and may eventually leave their mate to pair with him; some females are even unfaithful to their new partner by continuing to copulate with their "ex" after they have remated. However, nonmonogamous mates are not generally more likely to divorce than strictly monogamous pairs, and in fact some evidence suggests that Oystercatchers who engage in outside sexual activity are actually more likely to stay together. One study found that 0-5 percent of unfaithful birds divorced, while 11 percent of monogamous ones did. Many nonmonogamous matings are nonreproductive, occurring too early in the breeding season for fertilization to be possible, or between nonbreeders; in fact, only 2-5 percent of all chicks are the result of infidelities. There are several distinct categories of nonbreeders in this species, including nonbreeding pairs with territories (about 5 percent of all pairs) and FLOATERS without any territories. Overall, about 30 percent of the adult population is nonbreeding. Nevertheless, such birds still engage in sexual behavior, both with each other and with paired birds. Nonbreeding pairs and individuals also occur in Golden Plovers, and on average about half of the population is nonreproductive at any time.

Many within-pair copulations are also nonprocreative, with about 40 percent occurring too early or too late in the breeding season (for Oystercatchers), or during incubation. In addition, it has been estimated that each Oystercatcher pair copulates about 700 times during the breeding season — far in excess of the amount required for reproduction. Oystercatchers also sometimes practice nonreproductive REVERSE copulations, in which the female mounts the male. And as mentioned above, a quarter to a third of mounts between heterosexual mates do not involve genital contact; many such copulations are incomplete because the female throws the male off her back or otherwise refuses to participate. Much more rarely, a male will rape or forcibly copulate with a nonconsenting female. Adult-youngster interactions are also sometimes marked by violence and neglect: Oystercatcher chicks {543}

have been viciously attacked and even killed when they stray into another bird's territory. In addition, LEAPFROG parents often starve their chicks by failing to bring them enough food. Leapfrog birds are those whose nesting territories are located farther inland, separate from the feeding territories, hence to obtain food they must "leapfrog" over birds that nest directly adjacent to the shore. Studies have shown that the territories of such Oystercatchers do not, however, place undue time or energy constraints on them compared to nonleapfrogs. Thus, the fact that their chicks sometimes starve is due more to inadequate parental care than to their suboptimal territories.

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

Edwards, P. J. (1982) "Plumage Variation, Territoriality, and Breeding Displays of the Golden Plover Pluvialis apricaria in Southwest Scotland." Ibis 124:88-96.

* Ens, B. J. (1998) "Love Thine Enemy?" Nature 391:635-37.

* --- (1996) Personal communication.

--- (1992) "The Social Prisoner: Causes of Natural Variation in Reproductive Success of the Oystercatcher." Ph.D. thesis., University of Groningen.

Ens, B. J., M. Kersten, A. Brenninkmeijer, and J. B. Hulscher (1992) "Territory Quality, Parental Effort, and Reproductive Success of Oystercatchers (Haematopus ostralegus)." Journal of Animal Ecology 61:703-15.

Ens, B. J., U. N. Safriel, and M. P. Harris (1993) "Divorce in the Long-lived and Monogamous Oystercatcher, Haematopus ostralegus: Incompatibility or Choosing the Better Option?" Animal Behavior 45:1199-217.

Hampshire, J. S., and F. J. Russell (1993) "Oystercatchers Rearing Northern Lapwing Chick." British Birds 86:17-19.

Harris, M. P., U. N. Safriel, M. de L. Brooke, and C. K. Britton (1987) "The Pair Bond and Divorce Among Oystercatchers Haematopus ostralegus on Skokholm Island, Wales." Ibis 129:45-57.

* Heg, D. (1998) Personal communication.

Heg, D., B. J. Ens, T. Burke, L. Jenkins, and J. P. Kruijt (1993) "Why Does the Typically Monogamous Oystercatcher (Haematopus ostralegus) Engage in Extra-Pair Copulations?" Behavior 126:247-89.

* Heg, D., and R. van Treuren (1998) "Female-Female Cooperation in Polygynous Oystercatchers." Nature 391:687-91.

* Makkink, G. F. (1942) "Contribution to the Knowledge of the Behavior of the Oyster-Catcher (Haematopus ostralegus L.)." Ardea 31:23-74.

* Nethersole-Thompson, D., and C. Nethersole-Thompson (1961) "The Breeding Behavior of the British Golden Plover." In D. A. Bannerman, ed., The Birds of the British Isles, vol.10, pp. 206-14. Edinburgh and London: Oliver and Boyd.

* Nethersole-Thompson, D., and M. Nethersole-Thompson (1986) Waders: Their Breeding, Haunts, and Watchers. Calton: T. and A. D. Poyser.

Parr, R. (1992) "Sequential Polyandry by Golden Plovers." British Birds 85:309.

--- (1980) "Population Study of Golden Plover Pluvialis apricaria, Using Marked Birds." Ornis Scandinavica 11:179-89.

--- (1979) "Sequential Breeding by Golden Plovers." British Birds 72:499-503.

Tomlinson, D. (1993) "Oystercatcher Chick Probably Killed by Rival Adult." British Birds 86:223-25.

{544}

GULLS AND TERNS

Gulls

Gulls

RING-BILLED GULL (Larus delawarensis)

IDENTIFICATION: A medium-sized (21 inch) gull with a gray back and wings; spotted black-and-white wing tips; yellow bill, legs, and eyes; and a black band on the bill. DISTRIBUTION: Central Canada, much of United States; winters south to Central America. HABITAT: Coasts, rivers, lakes, prairies. STUDY AREAS: Eastern Oregon and Washington State; Granite Island, Lake Superior; Ile de la Couvee, near Montreal; Gull Island, Lake Ontario; other locations on Lakes Erie, Ontario, and Huron.

COMMON GULL (Larus canus)

IDENTIFICATION: Similar to Ring-billed Gull, except slightly smaller (up to 18 inches) and with a more slender, plain yellow bill. DISTRIBUTION: Nearly circumpolar in Northern Hemisphere; winters south to North Africa, East Asia, California. HABITAT: Coasts, mudflats, beaches, lakes. STUDY AREA: Fair Isle on the Shetland Islands, Scotland; subspecies

L.c. canus.

Social Organization

Common Gulls are fairly sociable, often associating in flocks of up to 100 individuals; sometimes tens of thousands of birds congregate outside of the breeding season. Ring-billed Gulls are also gregarious. Birds of both species generally form monogamous pair-bonds (although several variations exist — see below). Nesting colonies in Common Gulls contain a few dozen to several hundred pairs, while Ring-billed colonies can be much larger, in the tens of thousands of pairs.

{545}

Description

Behavioral Expression: Both Ring-billed and Common Gull females sometimes develop homosexual bonds, build nests together, lay and incubate eggs, and successfully raise chicks. Same-sex pairs are often long-lasting (as are heterosexual pair-bonds in these species), and females generally return to the same nest site with their female partner each year. Of five homosexual pairs of Ring-billed Gulls tracked over time, for example, all remained together over more than one mating season, while homosexual bonds lasting for at least eight years have been documented in female Common Gulls. Some pairs do divorce between mating seasons, however, as do some heterosexual pairs. In addition, female Ring-billed Gulls on rare occasions switch mates during a mating season, first pairing with one female, then with another. Same-sex bonds in this species also show a number of other interesting features that are rarely found in female homosexual bonds in other animals. For example, one or both partners in a homosexual pair are often younger females: couples in which there is an age difference between the two females — one an adult, the other an adolescent or younger adult — are particularly common in some populations. In addition, some female Ring-billed Gulls form homosexual trios consisting of three birds that are all simultaneously bonded to one another. In Common Gulls, homosexual pairs may after several years develop into bisexual trios. This occurs when a male joins them and is accepted into their association, bonding with one or both females (who nevertheless still retain their bond with each other). In Ring-billed Gulls, the opposite scenario may occur: in at least one case, two females in a bisexual trio remained paired to each other after the male left their association. Ring-billed Gulls in homosexual pairs probably do not engage in a great deal of courtship activity (unlike heterosexual or homosexual pairs in other species).

The first breeding season that female Common Gulls begin a pair-bond, they may build a "double nest" consisting of two separate but touching nest cups; in subsequent years, they will build only a single nest in which they both lay eggs (like most Ring-billed female pairs). Since both partners usually lay eggs, nests of homosexual pairs often contain "oversize" or SUPERNORMAL CLUTCHES of 5-8 eggs (Ring-billed Gull) and 6 eggs (Common Gull) — up to twice the number found in heterosexual nests. Some Ring-billed Gulls in female couples may also lay their eggs in the nests of other (heterosexual) pairs. One or both partners in pairs of female Ring-billed Gulls may mate nonmonogamously with a male so that some of their eggs will be fertilized. Female Common Gulls in bisexual trios can also lay fertile eggs by mating with their male partner. Both females share incubation duties and also cooperate in parenting the chicks that they hatch. Homosexual parents in Ring-billed Gulls invest as much time as their heterosexual counterparts do in feeding their chicks, spending time on the nesting territory, and defending their territory. They may actually work harder than male-female pairs in brooding and defending their chicks, with the result that offspring of female pairs often have a faster growth rate than chicks of heterosexual parents.

Nevertheless, chicks belonging to female pairs are often less robust on hatching, and female parents generally raise less than half the number of chicks that male-female pairs do. However, these traits are also characteristic of supernormal {546}

clutches belonging to heterosexual trios and are therefore undoubtedly related to the larger clutch size rather than the sex or abilities of the parents. In addition, in some populations female pairs are relegated to smaller, substandard territories on the periphery of the breeding colony or in between other territories (as are less experienced heterosexual pairs). In some cases, homosexual pairs actually appear to form clusters of up to ten nests in close proximity, or else small groups of two or three (sometimes in a straight-line or triangular formation). Many of these nests are located in areas where it is more difficult to parent successfully — places with little or no vegetation, or else away from the beach — and therefore it is remarkable that female pairs are able to successfully raise chicks as often as they do in such less than optimal conditions.

Frequency: There is wide variation in the incidence of female pairing in Ring-billed Gulls. In some populations — especially in growing colonies — as many as 6-12 percent of the pairs are homosexual. In other colonies, they are less common — 1-3 percent of all pairs — and in some locations as few as 1 in 700 or 1 in 3,400 nests may belong to a female pair. Overall, pair-bonds between females probably occur only occasionally in Common Gulls, although at one study site, 1 pair out of a total of 12 was homosexual.

Orientation: There is an equally wide variation in the proportion of heterosexual, bisexual, and homosexual orientations among Ring-billed Gulls. In some populations, less than a third of all eggs laid by female pairs are fertile, indicating that the majority of such females are exclusively homosexual (at least for the duration of their pair-bond). In other colonies, egg fertility of female pairs is much higher — two-thirds to nearly 90 percent — indicating a greater prevalence of bisexual activity. Even among such females, however, there is further variation. In some same-sex couples, both females mate with males and lay fertile eggs; in others, only one partner does, or each partner might lay both fertile and infertile eggs at different times, indicating temporal variation in bisexual activity. Similarly, in a Common Gull bisexual trio, one female remained exclusively homosexual even though her female partner mated with the male. In addition, a large number of "heterosexual" Ring-billed females may have a "latent" bisexual potential, since many are able to develop bonds with other females if single males are not available.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Heterosexual pairs in Ring-billed and Common Gulls exhibit a variety of bonding and parenting arrangements (like homosexual pairs). Not all males and females couple for life: the heterosexual divorce rate is about 28 percent in both species. Polygamous heterosexual trios — two females bonded to the same male, but not to each other — are also found in both species, as are occasionally even quartets (three females with one male). Common Gull pairs sometimes foster-parent chicks, while another form of "adoption" occurs in these species when females occasionally lay eggs in nests belonging to other pairs or roll eggs from other nests into their own. {547}

Moreover, because of parental ineptitude or inefficiency (such as poor feeding), at least 8 percent of Ring-billed chicks abandon or "run away" from their own families; most of these are adopted and cared for by other families.

About 4 percent of Ring-billed pairs continue to engage in courtship and copulation after the hatching of their eggs — when sexual activity is not directly reproductive — and about 5 percent of adults court and mount chicks. Most of this activity involves females behaving incestuously with their own offspring, including full copulatory REVERSE mounts of young birds. Mounted chicks may be as young as two weeks old, and they usually collapse under the weight of the adult mounting them and cry out in distress. Some individuals appear to be "habitual molesters" in that they repeatedly interact sexually with chicks, including their own. In addition to sexual molestation, Ring-billed chicks are often subjected to vicious attacks from neighboring adults when their parents are away, or if they stray outside of their home territory. About 1 in 300 chicks is killed by such assaults, and infanticide can account for between 5 percent and 80 percent of all chick deaths (depending on the population).

Other Species

Female pairs that lay supernormal clutches also occur in California Gulls (Larus californicus), where they constitute about 1 percent of all pairs.

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

Brown, K. M., M. Woulfe, and R. D. Morris (1995) "Patterns of Adoption in Ring-billed Gulls: Who Is Really Winning the Inter-generational Conflict?" Animal Behavior 49:321-31.

* Conover, M. R. (1989) "Parental Care by Male-Female and Female-Female Pairs of Ring-billed Gulls." Colonial Waterbirds 12:148-51.

* --- (1984a) "Frequency, Spatial Distribution, and Nest Attendants of Supernormal Clutches in Ring-billed and California Gulls." Condor 86:467-71.

* --- (1984b) "Consequences of Mate Loss to Incubating Ring-billed and California Gulls." Wilson Bulletin 96:714-16.

* --- (1984c) "Occurrence of Supernormal Clutches in the Laridae." Wilson Bulletin 96:249-67.

* Conover, M. R., and D. E. Aylor (1985) "A Mathematical Model to Estimate the Frequency of Female-Female or Other Multi-Female Associations in a Population." Journal of Field Ornithology 56:125-30.

* Conover, M. R., and G. L. Hunt, Jr. (1984a) "Female-Female Pairings and Sex Ratios in Gulls: A Historical Perspective." Wilson Bulletin 96:619-25.

* --- (1984b) "Experimental Evidence That Female-Female Pairs in Gulls Result From a Shortage of Males." Condor 86:472-76.

* Conover, M. R., D.E. Miller, and G. L. Hunt, Jr. (1979) "Female-Female Pairs and Other Unusual Reproductive Associations in Ring-billed and California Gulls." Auk 96:6-9.

Emlen, J. R., Jr. (1956) "Juvenile Mortality in a Ring-billed Gull Colony." Wilson Bulletin 68:232-38.

Fetterolf, P. M. (1983) "Infanticide and Non-Fatal Attacks on Chicks by Ring-billed Gulls." Animal Behavior 31:1018-28.

--- (1984) "Ring-billed Gulls Display Sexually Toward Offspring and Mates During Post-Hatching." Wilson Bulletin 96:12-19.

* Fetterolf, P. M., and H. Blokpoel (1984) "An Assessment of Possible Intraspecific Brood Parasitism in Ring-billed Gulls." Canadian Journal of Zoology 62:1680-84.

* Fetterolf, P. M., P. Mineau, H. Blokpoel, and G. Tessier (1984) "Incidence, Clustering, and Egg Fertility of Larger Than Normal Clutches in Great Lakes Ring-billed Gulls." Journal of Field Ornithology 55:81-88.

* Fox, G. A., and D. Boersma (1983) "Characteristics of Supernormal Ring-billed Gull Clutches and Their Attending Adults." Wilson Bulletin 95:552-59. {548}

Kinkel, L. K., and W. E. Southern (1978) "Adult Female Ring-billed Gulls Sexually Molest Juveniles." Bird-Banding 49:184-86.

* Kovacs, K. M., and J. P. Ryder (1985) "Morphology and Physiology of Female-Female Pair Members." Auk 102:874-78.

* --- (1983) "Reproductive Performance of Female-Female Pairs and Polygynous Trios of Ring-billed Gulls." Auk 100:658-69.

* --- (1981) "Nest-site Tenacity and Mate Fidelity in Female-Female Pairs of Ring-billed Gulls." Auk 98:625-27.

* Lagrenade, M., and P. Mousseau (1983) "Female-Female Pairs and Polygynous Associations in a Quebec Ring-billed Gull Colony." Auk 100:210-12.

Nethersole-Thompson, C., and D. Nethersole-Thompson (1942) "Bigamy in the Common Gull." British Birds 36:98-100.

* Riddiford, N. (1995) "Two Common Gulls Sharing a Nest." British Birds 88:112-13.

* Ryder, J. P. (1993) "Ring-billed Gull." In A. Poole, P. Stettenheim, and F. Gill, eds., The Birds of North America: Life Histories for the 21st Century, no. 33. Philadelphia: Academy of Natural Sciences; Washington, D.C.: American Ornithologists Union.

* Ryder, J. P., and P. L. Somppi (1979) "Female-Female Pairing in Ring-billed Gulls." Auk 96:1-5.

Southern, L. K., and W. E. Southern (1982) "Mate Fidelity in Ring-billed Gulls." Journal of Field Ornithology 53:170-71.

Trubridge, M. (1980) "Common Gull Rolling Eggs from Adjacent Nest into Own." British Birds 73:222-23.

Gulls

Gulls

WESTERN GULL (Larus occidentalis)

IDENTIFICATION: A large gull (up to 27 inches) with a dark gray back and wings; spotted black-and-white wing tips; pink legs; and a yellow bill with a red spot. DISTRIBUTION: Pacific coast of North America. HABITAT: Cliffs, rocky seacoasts, bays. STUDY AREAS: Santa Barbara Island and other Channel Islands, California; subspecies L.o. wymani.

KITTIWAKE (Rissa tridactyla)

IDENTIFICATION: A smaller gull (to 17 inches) with a blue-gray mantle; more pointed black wing tips; relatively short black legs and dark eyes; and a yellowish green bill. DISTRIBUTION: Northern Pacific and Atlantic Oceans; adjacent Arctic Ocean. HABITAT: Oceangoing; breeds on coasts. STUDY AREA: North Shields, Tyne and Wear, England; subspecies R.t. tridactyla.

{549}

Social Organization

Western Gulls and Kittiwakes form pair-bonds and nest in colonies, some of which contain upwards of 10,000 pairs; Kittiwakes often nest on cliffs. Outside of the breeding season they are less sociable, occasionally gathering in loose aggregations when not solitary.

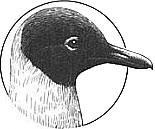

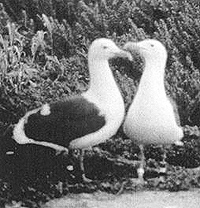

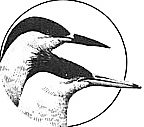

A homosexual pair of female Western Gulls in California

Description

Behavioral Expression: Female Western Gulls sometimes form homosexual pairs, as do Kittiwakes. In Western Gulls, the females participate in courtship, sexual, and parenting behaviors similar to those of heterosexual pairs in their basic patterns, yet different in many details. Two females court one another by performing HEAD-TOSSING (a stylized bobbing of the head with the bill pointed skyward) and COURTSHIP-FEEDING (in which a small amount of food is regurgitated and offered as a "gift" to the partner). In heterosexual pairs, males usually perform more courtship-feeding and females more head-tossing. In homosexual pairs, both birds perform these behaviors — often with equal frequency — although the overall rate of courtship behaviors for each female is similar to females in heterosexual pairs. Homosexual courtship-feeding differs from the heterosexual pattern in that a female does not offer as large an amount of food to her female partner and may even swallow the "offering" herself rather than give it to her mate. In some female pairs, one partner regularly mounts the other and may even utter the copulation call characteristic of heterosexual matings. Some females adopt unique mounting positions such as sideways or head-to-tail (not seen in heterosexual matings), and genital contact does not usually occur. Like heterosexual pairs, female couples establish territories that they defend against intruders. Both females spend a great deal of time on their territories (typical only of females in heterosexual pairs), while both also exhibit aggressive reactions to intruders (more typical of males in heterosexual pairs). Once a homosexual pair-bond is established, it usually persists for many years, and the two females return to the same territory each season: one study that tracked eight homosexual pairs found that seven of them remained together for more than one breeding season.

Homosexual pairs usually build a nest in which both females lay eggs; the resulting SUPERNORMAL CLUTCH contains 4-6 eggs in Western Gulls, up to twice the number found in nests of heterosexual pairs. Some of these eggs are fertile because females in homosexual pairs occasionally copulate with males (without breaking their same-sex bond). Although eggs laid by female {550}

pairs may be smaller than those of heterosexual females, homosexual parents successfully hatch and raise chicks, sharing all parental duties.

Frequency: As many as 10-15 percent of Western Gull pairs in some populations are homosexual; the percentage is much lower in Kittiwakes, about 2 percent of all pairs.

Orientation: Most female pairs in Kittiwakes are exclusively homosexual, never mating with males and laying only infertile eggs; the same is true for many pairs in Western Gulls. However, up to 15 percent of eggs laid by Western Gull same-sex pairs are fertilized, so at least some females are simultaneously bisexual — copulating with males while retaining their homosexual pair-bond.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Not all heterosexual birds in these species form lifelong, monogamous pair-bonds within which they raise their own young. About 30 percent of Kittiwake male-female pairs divorce. Some birds form polygamous trios consisting of one male bonded with two females, each with her own nest (about 3 percent of all bonds). Western Gull pairs (and rarely, single males) sometimes adopt and raise chicks that are not their own, and "stepmothering" occurs when females pair with a male that has lost his mate; foster-parenting also occurs in Kittiwakes (where about 8 percent of all chicks are adopted). In addition, many birds do not reproduce or do so only rarely: 30-40 percent of adult Western Gulls breed only once or twice in their lifetimes, and do not successfully raise any offspring, while 5 percent of all Kittiwakes that attempt to nest do not raise any young during their lives (and nearly two-thirds of all Kittiwakes never produce any offspring, usually because they die before breeding). Female Western Gulls that breed less often (or defer breeding until later in life) actually have higher survival rates than birds that reproduce more frequently. In Kittiwakes, nonbreeding birds form their own flocks or CLUBS on the outskirts of the breeding colonies. Western Gulls in heterosexual pairs also sometimes engage in nonprocreative sexual behaviors, such as REVERSE mounting (where the female mounts the male, typically without genital contact).

Some male Western Gulls are promiscuous, attempting to copulate with females other than their mates (usually birds on neighboring territories), although they are frequently unsuccessful. Occasionally a male will behave aggressively toward a female he has just mated with (nonmonogamously) and may even attack and kill her. Overall, more than 40 percent of aggressive incidents occur between members of the opposite sex. These include females defending themselves against promiscuous males, males attacking neighboring females that are courting them, and territorial disputes. Females may also refuse to copulate with their own mates, either by not allowing them to mount or by walking out from under them during mating. Some pairs, however, begin copulating even before the female's fertile period; this also occurs in Kittiwakes, and many copulations in this species do not involve genital contact (more than 30 percent). In Kittiwakes, 15-27 percent of all heterosexual copulations are harassed and interrupted by other males. Occasionally, adult {551}

Western Gulls are violent toward chicks, who may be attacked and even killed if left alone by their parents. Kittiwake parents (especially inexperienced ones) sometimes neglect their chicks (e.g., starving them), and birds may also attack or toss their own or other parents' chicks off cliffs. In fact, many adoptions and chick deaths in both species result from youngsters deserting or "running away" from their biological families as a result of neglect or direct attack. As many as a third of all Kittiwake chicks in some colonies abandon or are driven from their own nests. In addition, adults of both species may eat unattended eggs belonging to other parents.

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

* Baird, P. H. (1994) "Black-legged Kittiwake (Rissa tridactyla)." In A. Poole, P. Stettenheim, and F. Gill, eds., The Birds of North America: Life Histories for the 21st Century, no. 92. Philadelphia: Academy of Natural Sciences; Washington, D.C.: American Ornithologists' Union.

Carter, L. R., and L. B. Spear (1986) "Costs of Adoption in Western Gulls." Condor 88:253-56.

Chardine, J. W. (1987) "The Influence of Pair-Status on the Breeding Behavior of the Kittiwake Rissa tridactyla Before Egg-Laying." Ibis 129:515-26.

--- ((1986) "Interference of Copulation in a Colony of Marked Black-legged Kittiwakes." Canadian Journal of Zoology 64:1416-21.

* Conover, M. R. (1984) "Occurrence of Supernormal Clutches in the Laridae." Wilson Bulletin 96:249-67.

* Coulson, J. C., and C. S. Thomas (1985) "Changes in the Biology of the Kittiwake Rissa tridactyla: A 31 Year Study of a Breeding Colony." Journal of Animal Ecology 54:9-26.

--- (1983) "Mate Choice in the Kittiwake Gull." In P. Bateson, ed., Mate Choice, pp. 361-76. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Coulson, J. C., and E. White (1958) "The Effect of Age on the Breeding Biology of the Kittiwake Rissa tridactyla." Ibis 100:40-51.

Cullen, E. (1957) "Adaptations in the Kittiwake to Cliff-Nesting." Ibis 99:275-302.

* Fry, D. M., C. K. Toone, S. M. Speich, and R. J. Peard (1987) "Sex Ratio Skew and Breeding Patterns of Gulls: Demographic Toxicological Considerations." Studies in Avian Biology 10:26-43.

Hand, J. L. (1986) "Territory Defense and Associated Vocalizations of Western Gulls." Journal of Field Ornithology 57:1-15.

* --- (1980) "Nesting Success of Western Gulls on Bird Rock, Santa Catalina Island, California." In D. M. Power, ed., The California Islands: Proceedings of a Multidisciplinary Symposium, pp. 467-73. Santa Barbara: Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History.

* Hayward, J. L., and M. Fry (1993) "The Odd Couples/The Rest of the Story." Living Bird 12:16-19.

* Hunt, G. L., Jr. (1980) "Mate Selection and Mating Systems in Seabirds." In J. Burger, B. L. Olla, and H. E. Winn, eds., Behavior of Marine Mammals, vol. 4, pp. 113-51. New York: Plenum Press.

* Hunt, G. L., Jr., and M. W. Hunt (1977) "Female-Female Pairing in Western Gulls (Larus occidentalis) in Southern California." Science 196:1466-67.

* Hunt, G. L., Jr., A. L. Newman, M. H. Warner, J. C. Wingfield, and J. Kaiwi (1984) "Comparative Behavior of Male-Female and Female-Female Pairs Among Western Gulls Prior to Egg-Laying." Condor 86:157-62.

* Hunt, G. L., J. C. Wingfield, A.L. Newman, and D. S. Farner (1980) "Sex Ratio of Western Gulls on Santa Barbara Island, California." Auk 97:473-79.

Paludan, K. (1955) "Some Behavior Patterns of Rissa tridactyla." Videnskabelige Meddelelser fra Dansk naturhistorisk Forening 117:1-21.

Pierotti, R. J. (1991) "Infanticide versus Adoption: An Intergenerational Conflict." American Naturalist 138:1140-58.

* --- (1981) "Male and Female Parental Roles in the Western Gull Under Different Environmental Conditions." Auk 98:532-49.

--- (1980) "Spite and Altruism in Gulls." American Naturalist 115:290-300.

* Pierotti, R. J., and C. A. Annett (1995) "Western Gull (Larus occidentalis)." In A. Poole and F. Gill, eds., The Birds of North America: Life Histories for the 21st Century, no. 174. Philadelphia: Academy of Natural Sciences; Washington, D.C.: American Ornithologists' Union.

Pierotti, R. J., and E. C. Murphy (1987) "Intergenerational Conflicts in Gulls." Animal Behavior 35:435-44.

Pyle, P., N. Nur, W. J. Sydeman, and S.D. Emslie (1997) "Cost of Reproduction and the Evolution of Deferred Breeding in the Western Gull." Behavioral Ecology 8:140-47. {552}

Roberts, B. D., and S. A. Hatch (1994) "Chick Movements and Adoption in a Colony of Black-legged Kittiwakes." Wilson Bulletin 106:289-98.

Thomas, C. S., and J. C. Coulson (1988) "Reproductive Success of Kittiwake Gulls, Rissa tridactyla." In T. H. Clutton-Brock, ed., Reproductive Success: Studies of Individual Variation in Contrasting Breeding Systems, pp. 251-62. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

* Wingfield, J. C., A. L. Newman, G. L. Hunt, Jr., and D. S. Farner (1982) "Endocrine Aspects of Female-Female Pairings in the Western Gull, Larus occidentalis wymani." Animal Behavior 30:9-22.

* Wingfield, J. C., A. L. Newman, M. W. Hunt, G. L. Hunt, Jr., and D. Farner (1980) "The Origin of Homosexual Pairing of Female Western Gulls (Larus occidentalis wymani) on Santa Barbara Island." In D. M. Power, ed., The California Islands: Proceedings of a Multidisciplinary Symposium, pp. 461-66. Santa Barbara, Calif.: Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History.

Gulls

Gulls

SILVER GULL (Larus novaehollandiae)

IDENTIFICATION: A medium-sized (16 inch) gull with gray back and wings; spotted black-and-white wing tips; bright red bill and legs; white iris. DISTRIBUTION: Australia, New Zealand, New Caledonia. HABITAT: Coasts, lakes, islands. STUDY AREA: Kaikoura Peninsula, New Zealand; subspecies L.n. scopulinus, the Red-billed Gull.

HERRING GULL (Larus argentatus)

IDENTIFICATION: Similar to Silver Gull except larger (2 feet long), legs pinkish, bill yellow with a red spot, and iris yellow. DISTRIBUTION: North America, western Europe, Siberia; winters in Central America, N. Africa, southern Asia. HABITAT: Coasts, bays, lakes, rivers. STUDY AREAS: Gull Island National Wildlife Refuge, Lake Michigan; numerous other island locations in Lake Michigan, Lake Huron, and the Straits of Mackinac; Bird Island, Memmert, Germany; subspecies L.a. smithsonianus and

L.a. argentatus.

Social Organization

Silver and Herring Gulls are usually found in flocks of several hundreds or thousands; they generally form monogamous pair-bonds and nest in colonies containing anywhere from several hundred to tens of thousands of nests.

{553}

Description

Behavioral Expression: In both Silver and Herring Gulls, females sometimes form lesbian pairs while males occasionally participate in homosexual mountings. Female pairs may develop between birds who were previously paired to a male, or they may involve birds who have never been paired before. In some cases, single, nonbreeding Herring Gull females visit the territory of a heterosexual pair and court the female, for example by performing HEAD-TOSSING, in which the head is hunched down and then repeatedly flicked upward. The heterosexually paired birds usually respond aggressively, but sometimes this behavior leads to a homosexual pairing the following season. Like heterosexual pairs, homosexual bonds are usually long-lasting and renewed each year: of those Herring Gull females in homosexual pairs that return to the same breeding grounds, 92 percent pair with the same female (compared to 93 percent of birds in heterosexual pairs). Of those that divorce, some remain single while others find a new (female) mate.

Females in same-sex pairs usually build nests and lay eggs. Silver Gull homosexual females generally begin nesting at a younger age than heterosexual females: females paired to other females start on average about a year earlier than females paired to males, and 11 percent of homosexual females begin nesting when they are two years old (heterosexual females never begin this early). Since both females lay eggs, nests belonging to same-sex pairs often have double or more the number of eggs found in nests of heterosexual pairs. These SUPERNORMAL CLUTCHES contain 4 or more eggs in Silver Gulls (compared to 2 eggs for male-female pairs) and 5-7 eggs in Herring Gulls (compared to 3 eggs for heterosexual pairs). Females sometimes mate nonmonogamously with males — or are raped by them (see below) — while still remaining paired to their female partner. Consequently, some of the eggs laid by female pairs are fertile — about a third in Silver Gulls, and 4-30 percent in Herring Gulls. Homosexual parents often successfully hatch these eggs and raise the chicks. Approximately 3-4 percent of all Silver Gull chicks are raised by same-sex pairs, and a further 9 percent of chicks are raised by male-female pairs in which the mother is bisexual. Overall, 7 percent of birds that go on to become breeding adults in this species come from families with two female parents. However, homosexual and bisexual females generally produce fewer offspring during their lifetimes than do heterosexual females.

In both Silver and Herring Gulls, males in heterosexual pairs often try to copulate with birds other than their mates, and in some cases they mount other males. Like females who are mounted by birds other than their mate, male Herring Gulls may respond aggressively to another male's mounting them.

Frequency: About 6 percent of all pair-bonds in Silver Gulls are homosexual, while nesting attempts by female pairs occur in approximately 12 percent of all breeding seasons. In some populations of Herring Gulls, nearly 3 percent of the pairs are homosexual, while in other populations they are much less frequent, about 1 in every 360 pairs. In addition, approximately 2 percent of courtship behavior by unpaired females interacting with heterosexual pairs is directed toward {554}

the female partner. Male homosexual mountings account for 10 percent of the nonmonogamous copulations in Silver Gulls, and 2 percent of the total number of copulations; they are probably much less common in Herring Gulls.

Orientation: In Silver Gulls, 21 percent of females pair with another female at least once in their lifetimes; 10 percent are exclusively lesbian, mating only with other females during their lives, while 11 percent are (sequentially) bisexual, pairing with both males and females. In one study of Herring Gull homosexual pairs, six out of eight females had been in heterosexual pairs the previous year and formed same-sex bonds with each other when their male mates did not return. Of the remaining birds, one paired with a female after her male partner re-paired with another female, while the other had been a single nonbreeder prior to developing a same-sex pair-bond. In addition, female Herring Gulls may show a "preference" for homosexual pairings, since they sometimes re-pair with another female following the breakup of a same-sex bond. In both species, some females in homosexual pairs copulate with males in order to fertilize their eggs, still retaining their primary homosexual bond. Males that initiate homosexual mountings, while functionally bisexual, are probably primarily heterosexually oriented, since they are usually paired to females and rarely engage in same-sex behavior.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities