<<< >>>

{566}

Perching Birds and Songbirds

COTINGAS, MANAKINS, AND OTHERS

Cotingas

Cotingas

GUIANAN COCK-OF-THE-ROCK (Rupicola rupicola)

IDENTIFICATION: A small (10 inch) perching bird; adult males are brilliant orange with elaborate fringed wing plumes and an imposing helmetlike feather crest; adolescent males have mottled brown and orange plumage, while females are uniformly dark. DISTRIBUTION: Northern South America, primarily in southern Venezuela, the Guianas, adjacent parts of Brazil. HABITAT: Forests, usually near cliffs, mountains, or rock outcrops (on which females build their nests, giving the bird its name). STUDY AREA: Raleigh falls-Voltzberg Nature Reserve, Suriname, South America.

Social Organization

The spectacularly plumed Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock has what is known as a LEK social and mating system: males inhabit individual territories, usually clustered in the same area, which are used for display and courtship. Each display "court" consists of a cleared area on the forest floor and surrounding perches. Territories are maintained year-round, but courtship and mating occur only from late December through April. Females (and in this species, young males) visit these territories to choose which males they want to mate with. Other than this, males and females lead virtually separate lives: males do not participate in any aspect of nesting or parental care and rarely encounter females outside of the breeding season.

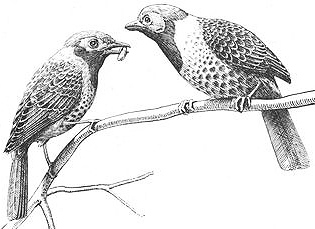

A younger (adolescent) male Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock mounting a bright orange adult male in the forests of Suriname

{567}

Description

Behavioral Expression: Homosexual activity between adult and adolescent males, as well as among adolescent males, is a routine occurrence in Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock. Males court and display to each other, as well as engage in homosexual mounting. A typical homosexual encounter begins when the adult males are perched beside their display courts, each glowing like an orange beacon in the jungle gloom. Both females and adolescent (yearling) males are attracted to the lek, which is carefully situated in the forest to take advantage of the ambient light characteristics of the environment (thereby showing off its owner to his best advantage). The courtship sequence commences with a GREETING DISPLAY: the males begin calling raucously, then each drops to the ground with a thump and begins beating his wings violently, flashing patches of black and white. This often produces a whistling sound as air rushes through the specially modified wing feathers.

This attention-grabbing sequence is followed by the GROUND DISPLAY: each adult male crouches down, fanning out the delicate filaments of his wing coverts, puffing out his chest and rump feathers and erecting his crest, resulting in a spectacular visual effect. By this time an adolescent male who is attracted by the display has landed beside the adult and is hopping about the display court, often crouching in a version of the courtship posture himself. The adult keeps his back toward the younger male at all times but is otherwise motionless, showing off his plumage to its best and inviting the adolescent to mount him. During homosexual copulation, the younger male climbs onto the adult's back and perches firmly, moving his tail sideways to try to make genital contact. Often the younger male mounts the older male several times in succession, and courtship and display often alternate with mountings. Sometimes males also mount each other in the trees surrounding a display court. Homosexual interactions differ from heterosexual ones in that both participants perform some version of the ground display; also, unlike females, neither male pecks at or touches the other's rump prior to mounting.

Adolescent males usually visit the display courts of several adult males, although some adults are clearly more "popular" than others because they receive more attention from the younger males. Typically, a yearling has homosexual interactions with anywhere from one to seven different adult males during the mating season. Nor does homosexual activity always involve an adult territory owner and a yearling male: adolescents often mount nonbreeding males who do not have their own display territories and sometimes also mount other adolescent males. Homosexual activity is not separate from heterosexual courtship and copulation, {568}

but takes place in the same locations and often while male-female interactions are happening in the vicinity. However, homosexual courtship and mounting often take priority over heterosexual interactions. If an adolescent male approaches an adult who is courting a female, the female usually leaves (or is chased away), and the two males turn their attentions to each other. Moreover, if a female encounters a male who is courting or involved sexually with another male, she usually waits until the adolescent male leaves before approaching the adult.

Frequency: Homosexual activity is very common among Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock: in fact, mountings between males are as frequent as male-female mountings, accounting for nearly half of all copulations. About 10 percent of heterosexual courtships are interrupted by adolescent males visiting the courting male; roughly one out of five of these "interruptions" involves courtship or sexual behavior between males. During the breeding season, homosexual activity may occur daily, and an adolescent male will usually have 6-7 homosexual encounters over the season (although some males engage in homosexual mounting more frequently, 15 or more times over a season).

Orientation: Close to 40 percent of the male population participates in some form of homosexual activity. Depending on his age, a bird that has same-sex interactions may or may not also engage in heterosexual activity. Among adult males (three years or older), nearly a quarter (23 percent) are mounted by other males, and 6 percent of these do not mate or court females at all. In fact, those adults who do not mate heterosexually are often the ones most frequently mounted by younger males. Among yearling males (virtually none of whom mount females), almost two-thirds (64 percent) engage in homosexual activity. Two-year-old males, on the other hand, very rarely engage in homosexual activity. Thus, when birds of all ages are taken into account, nearly 20 percent of the male population at any given time is involved exclusively in homosexuality.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

As described above, male and female Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock have essentially no contact with each other outside of the mating season. Even during the breeding season, their interactions are often unfriendly or overtly aggressive. Males frequently harass females by chasing them around the display court and in some cases attempt to forcibly copulate with them. Females struggle violently during these rape attempts and are usually able to get away, but are visibly stressed following such interactions. In fact, only 20 percent of all lek visits by females result in copulation. There is also a significant proportion of nonbreeding individuals in the population: an average of 20 percent of adult males do not have display territories (and thus rarely, if ever, court or mate with females), while nearly two-thirds of territorial males fail to mate each year. Moreover, males are rarely able to acquire their own territories (and therefore court females) before they are three to four years old. In addition, many females who visit the courtship grounds never actually mate with males during the entire breeding season.

{569}

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

Endler, J. A., and M. Thery (1996) "Interacting Effects of Lek Placement, Display Behavior, Ambient Light, and Color Patterns in Three Neotropical Forest-Dwelling Birds." American Naturalist 148:421-52.

Gilliard, E. T. (1962) "On the Breeding Behavior of the Cock-of-the-Rock (Aves, Rupicola rupicola)." Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 124:31-68.

Trail, P. W. (1989) "Active Mate Choice at Cock-of-the-Rock Leks: Tactics of Sampling and Comparison." Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 25:283-92.

* --- (1985a) "A Lek's Icon: The Courtship Display of a Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock." American Birds 39:235-40.

--- (1985b) "Courtship Disruption Modifies Mate Choice in a Lek-Breeding Bird." Science 227:778-80.

* --- (1983) "Cock-of-the-Rock: Jungle Dandy." National Geographic Magazine 164:831-39.

* Trail, P. W., and D. L. Koutnik (1986) "Courtship Disruption at the Lek in the Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock." Ethology 73:197-218.

Cotingas

Cotingas

CALFBIRD (Perissocephalus tricolor)

IDENTIFIfATION: A crow-sized bird with cinnamon-brown plumage and a bare, blue-gray face. DISTRIBUTION: North-central South America, including Venezuela, the Guianas, Amazonian Brazil. HABITAT: Tropical forest. STUDY AREAS: Brownsberg Nature Park, Suriname; near the Kanuku Mountains, Guyana.

Social Organization

Calfbird males congregate, eight to ten at a time, on a display area or LEK in the understory of the rain forest canopy. Each lek consists of a central perch occupied by only one male, around which the remaining males cluster. Females (and males) visit the central male during courtship, usually at dawn; mating is polygamous or promiscuous, and females nest and raise the young on their own.

Description

Behavioral Expression: Male Calfbirds sometimes court other males who are attracted to the leks. A homosexual courtship begins when one male approaches {570}

the display site in a posture that females also adopt when entering the lek: the body is held in a horizontal position and all of the feathers are sleeked down, including the cowl feathers. He is attracted by the dramatic display of the central male, which consists of a loud, droning MOO call (hence the bird's name) sounding something like grr-aaa-oooo. While mooing, the displaying male first puffs himself up, fluffing up his cowl feathers, and then sinks back down in a bowing motion while exposing two bright orange feather globes on either side of his tail. The male in horizontal posture gets close to the mooing bird, who may then direct his courtship displays directly at the other male — for example, by hopping closer while mooing intensely, or engaging in ritualized wing-preening. Usually the approaching male is then chased away if he gets too close, and in fact no homosexual copulations have yet been observed in this species. However, heterosexual mating itself is fairly rare (only occurring in 14 percent of dawn courtship visits by females), and displaying males also frequently chase females who approach them. Furthermore, males do sometimes mount or attempt to mount other males outside of the lek, though this may occur in an aggressive context. Calfbirds also typically form "companionships" with each other: the two males perform coordinated courtship displays, almost touching as they perch side by side, while they both moo and bow in precise alternation. In some cases, companions never perform courtship displays without their male partner. Companions also travel together on the lek and may even share a "home" with each other. Calfbirds typically have what is known as a RETREAT, a special location or tree where each male regularly spends time when not on the lek. Display partners sometimes share the same retreat.

Female Calfbirds also develop bonds with one another: the two companions keep each other company while feeding, travel together to and from the lek, and even nest close to each other. This is all the more remarkable considering that there are no heterosexual pair-bonds in this species. Female pairs use a number of distinctive calls to communicate with each other. While feeding together, for example, they maintain contact with soft wark calls. When one female sits on her nest, the other may perch nearby uttering a rasping waaa call regularly for over an hour, perhaps acting as a lookout for her companion. And two females nesting close to each other sometimes communicate with a unique low, growling call that sounds like grewer grewer, which is only heard in this context. Although no same-sex courtship or copulation has yet been observed, females do sometimes perform behaviors that are typically associated with displaying males. For example, one female was seen to call and posture repeatedly in the fashion of a male courting on a lek (though she did this away from the lek, at her nest). Her call was like the first half of the male's mooing, and she displayed the orange tail ornaments usually seen in the male's courtship sequence. Her voice was also raspier than other females', and she built an exceptionally large nest. In addition, females sometimes adopt the male's characteristic upright and fluffed appearance when they visit the lek.

Frequency: Approximately 1-2 percent of all courtship visits involve one male displaying to another, and all males (except for the central one) have male display {571}

partners. Mounting attempts between males occur fairly frequently, but it is not known how prevalent female same-sex activities are.

Orientation: Because only the central male ever copulates with females, the remainder of the male population is effectively involved only in same-sex activities for the duration of the breeding season, whether display companionships or courtship/mounting with other males. The central male, however, displays mostly to females and occasionally to males, so his behavior is bisexual — albeit primarily heterosexual. In addition, in the next breeding season another male may become the central one, so at least some of the males exhibit sequential bisexuality, while the remainder may continue to experience longer periods of more exclusive homosexuality.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

As discussed above, the majority of the male population in any given year does not reproduce: only one male (the central one in the lek) ever breeds with a female. Moreover, only 12 percent of females mate during their dawn courtship visits, and heterosexual relations are frequently fraught with difficulty. Copulations are brief, often incomplete, and accompanied by aggression. Females visiting the lek are constantly chased by the noncentral males, while nearly one-third of male-female copulations and more than half of all courtship visits are disrupted and harassed by other Calfbirds.

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

* Snow, B. K. (1972) "A Field Study of the Calfbird Perissocephalus tricolor." Ibis 114:139-62.

--- (1961) "Notes on the Behavior of Three Cotingidae." Auk 78:150-61.

Snow, D. (1982) The Cotingas: Bellbirds, Umbrellabirds, and Other Species. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

* --- (1976) The Web of Adaptation: Bird Studies in the American Tropics. New York: Quadrangle/New York Times Book Co.

* Trail, P. W. (1990) "Why Should Lek-Breeders Be Monomorphic?" Evolution 44:1837-52.

{572}

Manakins

Manakins

SWALLOW-TAILED MANAKIN (Chiroxiphia caudata)

IDENTIFICATION: Adult males are bright blue with an orangish red crown and a black head and wings; females and yearling males are all green, while younger adult males are green or blue-green with an orange crown. DISTRIBUTION: Eastern Brazil, Paraguay, northwestern Argentina. HABITAT: Moist forests. STUDY AREA: Southeastern Brazil.

BLUE-BACKED MANAKIN (Chiroxiphia pareola)

IDENTIFICATION: Adult males are black with a red crown and a light blue patch on the back; yearling males and females are all green, while younger adult males are green with a reddish crown. DISTRIBUTION: Tobago, the Guianas, the Amazon Basin. HABITAT: Forest undergrowth, woodland. STUDY AREA: Tobago, West Indies; subspecies

C.p. atlantica.

Social Organization

Male Swallow-tailed Manakins form stable, long-term associations of four to six individuals that spend virtually all of their time together; they remain with each other throughout the mating season and usually from year to year as well. These groups display together on traditional courts or LEKS. The mating system is polygamous, with males (and probably also females) copulating with multiple partners, although large numbers of males are nonbreeders. Blue-backed Manakins have a similar social organization.

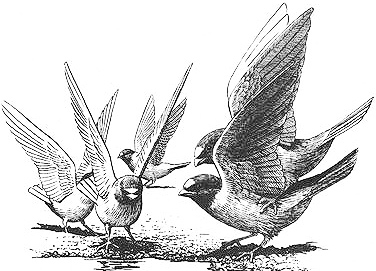

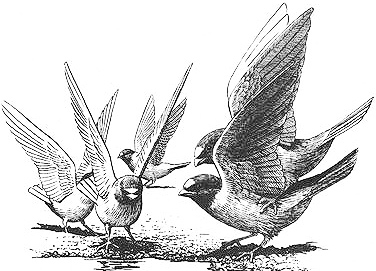

Homosexual courtship in a group of Swallow-tailed Manakins: one male (right) hovers in front of a younger male as the other males prepare to perform their part in the "jump display"

Description

Behavioral Expression: Male Swallow-tailed Manakins perform an elaborate group courtship ritual, the JUMP DISPLAY. Sometimes this display is directed toward females, sometimes toward yearling or younger adult males (the latter resembling females in their green plumage, but distinct because of their red-orange caps), and less commonly toward another adult male. To begin a homosexual jump display, a group of two to three adult males gathers on a display perch on their lek, lined up side by side, with the (younger) male they are displaying to perched at the head of this row. While uttering squawking notes that resemble a chorus of frogs, the adult {573}

males crouch down, quiver their bodies, and shuffle their feet, forming a collective vibrating mass. The courting males then take turns jumping up and hovering in front of the younger male while giving a sharp dik-dik-dik call, landing next to him. As each male jumps, the others slide down the perch toward his former position, repeating the sequence each time to produce a continuous rotation of flying and sliding birds, whose orange-red crowns collectively form a "whirling torch" in front of the courted bird. During this coordinated display, the younger male usually sits motionless in an upright posture. Males also sometimes mount each other and attempt copulation.

A similar revolving courtship display is performed by pairs of male Blue-backed Manakins for a third bird, which is sometimes a younger male. The display begins with a duet between the displaying males in order to attract a potential mate: the two birds perch side by side and utter perfectly synchronized chup calls. Once a younger male arrives, they begin courting him with their CATHERINE WHEEL DISPLAY. Each adult male jumps up alternately and flutters backward, "leapfrogging" over his partner, who moves forward to replace him in a precisely timed sequence that resembles two juggling balls. This is repeated up to 60 times to create a "cartwheel" of flying birds, oriented toward the male being courted, that gradually gets faster and faster. All the while the displaying males utter vibrant nasal or buzzing sounds that resemble the twanging of a Jew's harp. At the peak of the dancing frenzy, one of the adult males calls sharply and his partner disappears; the first male then begins courting the younger male one-on-one. He crisscrosses his display perch in a buoyant, butterfly-like flight, alighting in front of the other male every once in a while to lower his head, vibrate his wings and opalescent blue back, and display his brilliant red crest with its two extendable horns. During this performance, the younger male crouches and constantly turns to face the older male courting him, sometimes also responding with a similar bouncing "butterfly" flight across the display perch.

{574}

Frequency: The overall proportion of courtships or mounts that occur between males is not yet known for either of these species, although they may be relatively infrequent. However, two of three observed "butterfly" courtship displays in a study of Blue-backed Manakins were directed toward males, while in a two-year study of Swallow-tailed Manakins, only ten heterosexual matings were recorded. It is possible, therefore, that same-sex activity represents a sizable proportion of all courtship and/or sexual activity.

Orientation: Only one out of every four to six male Swallow-tailed Manakins displaying on the lek ever copulates with females; thus, a large proportion of males are not involved directly in male-female sexual (mounting) activity, although they do participate in both heterosexual and homosexual courtships. A similar pattern occurs in Blue-backed Manakins.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

In addition to significant numbers of nonbreeding males, Swallow-tailed Manakin populations are characterized by several other less-than-optimal heterosexualities. Only about a third of male-female courtships ever result in mating: half of the time, females being courted simply leave, while in the remainder of cases other males disrupt the courtship displays. However, when mating does take place, a female may copulate with the same male up to six times in one visit; the same is also true for Blue-backed Manakins.

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

Foster, M. S. (1987) "Delayed Maturation, Neoteny, and Social System Differences in Two Manakins of the Genus Chiroxiphia." Evolution 41:547-58.

--- (1984) "Jewel Bird Jamboree." Natural History 93(7):54-59.

--- (1981) "Cooperative Behavior and Social Organization in the Swallow-tailed Manakin (Chiroxiphia caudata)." Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 9:167-77.

Gilliard, E. T. (1959) "Notes on the Courtship Behavior of the Blue-backed Manakin (Chiroxiphia pareola )." American Museum Novitates 1942:1-19.

* Sick, H. (1967) "Courtship Behavior in the Manakins (Pipridae): A Review." Living Bird 6:5-22.

* --- (1959) "Die Balz der Schmuckvogel (Pipridae) [The Mating Ritual of Jewel Birds]." Journal fur Ornithologie 100:269-302.

* Snow, D. W. (1976) The Web of Adaptation: Bird Studies in the American Tropics. New York: Quadrangle /New York Times Book Co.

--- (1971) "Social Organization of the Blue-backed Manakin." Wilson Bulletin 83:3-38.

* --- (1963) "The Display of the Blue-backed Manakin, Chiroxiphia pareola, in Tobago, W.I." Zoologica 48:167-76.

{575}

Antbirds

Antbirds

BICOLORED ANTBIRD (Gymnopithys bicolor)

OCELLATED ANTBIRD (Phaenostictus mcleannani)

IDENTIFICATION: Small (5-7 inch) birds with brown and rufous plumage and a bluish gray patch around the eyes; Ocellateds have a distinctive scalloped pattern on the back feathers. DISTRIBUTION: Central America and northwestern South America from Honduras to Ecuador. HABITAT: Rain forest undergrowth. STUDY AREA: Barro Colorado Island, Panama.

Social Organization

Antbirds get their name because they follow large swarms of army ants for food, often in flocks containing several different bird species. Both Bicolored and Ocellated Antbirds form monogamous pairs that are generally long-lasting. In addition, Ocellated Antbirds live in a complex extended family or "clan" structure, typically containing up to three generations of males and their mates. Females emigrate from these units to join other clans, while males often return to their extended family once they have found mates.

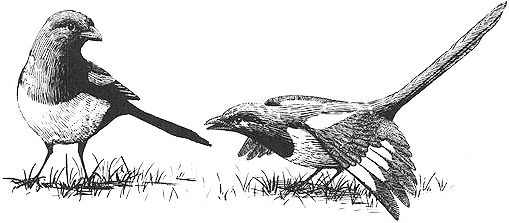

A male Ocellated Antbird (left) "courtship-feeding" his male pair-mate

Description

Behavioral Expression: Male homosexual pairs are a distinctive feature of Bicolored and Ocellated Antbird social life. Usually the pair-bond is initiated and strengthened (as in heterosexual pairs) when one male COURTSHIP-FEEDS the other, that is, ritually presents him with a "gift" of food (usually an insect or spider). In Ocellated Antbirds, males who court each other this way often adopt a characteristic pose (also used in heterosexual courtship) — ruffled throat feathers, stiff neck and upright posture, fluffed-out body feathers, with tail and legs spread. They also CAROL, producing a series of up to 15 whistled notes that decrease in pitch (sounding like chee chee chew chew). Unlike heterosexual mates, male partners typically reciprocate courtship feeding by passing the food gift back and forth between them. Homosexual courtship-feeding in Bicolored Antbirds is distinct from the heterosexual pattern in a number of other ways as well: either partner may initiate the activity in a male pair, and courtship-feeding is usually accompanied by CHIRPING — brief, musical cheup notes. In heterosexual pairs, only the male {576}

feeds the female, and the partners typically utter GROWLS during courtship-feeding (a rapid hissing or grunting noise composed of rough chauhh notes). Once paired, two males are constant companions, visiting ant swarms together and foraging side by side much as opposite-sex mated pairs do. Homosexual pair-bonds are sometimes long-lasting associations, persisting for many years. Partners may both be adults, or an older bird may pair with a younger one. In Ocellated Antbirds, father-son courtship-feedings also sometimes occur when a younger male remains within the clan structure.

Frequency: In Bicolored Antbirds, an estimated 2-3 percent of all pairs in some populations are composed of two males, and homosexual pairs may constitute up to 4-6 percent of the total number of pairs in any given year. The incidence of male pairs in Ocellated Antbirds is probably comparable.

Orientation: Approximately 5-14 percent of male Bicolored Antbirds may participate in a homosexual pairing or courtship at some point in their life. In both species, some males exhibit sequential bisexuality. In a few cases, for example, males have been mated to a female prior to their homosexual pairing (they may even have fathered young, and some are widowers), or they may go on to mate with a female when a homosexual pairing breaks up. Other males, however, show no signs of participating in heterosexual mating, and these birds may be involved exclusively in homosexual pairs, at least for a portion of their lives.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

In both Bicolored and Ocellated Antbirds, significant numbers of birds are nonbreeding. As many as 45 percent of adult Bicolored males may not be heterosexually paired in any given year, and some males fail to acquire a mate for six or more years in a row. Younger males may delay their reproductive careers for up to a year after reaching sexual maturity — by remaining "at home" in their clans (Ocellateds) or wandering solitarily (Bicoloreds). In addition, male Antbirds have been known to live to a relatively old age — more than 11 years in Bicoloreds and Ocel-lateds. For a few individuals who have lost their female partners (either through death or divorce), this may be a postreproductive period in their lives. In addition to females leaving their mates for younger males, divorce and mate-switching also occasionally happen in adult Bicolored and newly paired Ocellated Antbirds. Often, a divorce is {577}

initiated by "extramarital" courtship between a mated female and an unpaired male. The extended families of Ocellated Antbirds also sometimes break up: heterosexual pairs wander off from the clan if they have not been able to breed successfully, or grandparents isolate themselves from their relatives. Heterosexual relations within a pair are not always smooth either: in Bicoloreds, for example, males are often distinctly hostile to their female mates. This is especially true early in their pair-bond, when he may aggressively "blast" her off her perch with hissing and snapping. Female Ocellated Antbirds have also been observed steadfastly refusing the courtship and copulatory advances of males. Finally, a number of incestuous activities have been documented in these species, including courtship and attempted copulation between Ocellated males and their mothers, and courtship of Bicolored daughters by their fathers.

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

Willis, E.O. (1983) "Longevities of Some Panamanian Forest Birds, with Note of Low Survivorship in Old Spotted Antbirds (Hylophylax naevioides)." Journal of Field Ornithology54:413-14.

* --- (1973) The Behavior of Ocellated Antbirds. Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology no. 144. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

* --- (1972) The Behavior of Spotted Antbirds. Ornithological Monographs 10. Washington, D.C.: American Ornithologists' Union.

* --- (1967) The Behavior of Bicolored Antbirds. University of California Publications in Zoology 79. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Tyrant Flycatchers

Tyrant Flycatchers

OCHER-BELLIED FLYCATCHER (Mionectes oleagineus)

IDENTIFICATION: A small (5 inch), plain olive-green bird with a long tail and an ocher- or tawny-colored lower breast. DISTRIBUTION: From Mexico south to the Amazon in South America; Trinidad and Tobago. HABITAT: Humid lowland forests, open shrubbery. STUDY AREA: Corcovado National Park, Costa Rica; subspecies

M.o. dyscola.

{578}

Social Organization

Ocher-bellied Flycatchers have a complex social organization, with three distinct categories of males. About 42 percent of males are TERRITORIAL, defending "courts" in the foliage within which they perform courtship displays; sometimes groups of two to six territorial males display close to each other in a LEK formation. Another 10 percent of males are SATELLITES, who associate with territorial males but do not display; they often eventually inherit the territory themselves. Finally, 48 percent of males are FLOATERS, who travel widely and do not hold any territories themselves. The mating system of Ocher-bellies is polygamous or promiscuous. No male-female pair-bonds are formed; instead, males mate with as many females as they can, but the female raises the young on her own.

Description

Behavioral Expression: Female Ocher-bellied Flycatchers are usually attracted to males displaying and singing on their territories, but sometimes another male approaches and is courted by the territorial male. The approaching male behaves much like a female, moving toward the center of the display court flicking his wings while the other male sings more intensely (making whistlelike notes), crouching and wing-flicking. The territorial male then trails the other male, following him closely and sometimes making soft ipp calls. The courtship sequence continues as in a heterosexual encounter with a series of three types of flight displays by the territorial male. The HOP DISPLAY involves the male bouncing excitedly back and forth between two perches uttering an eek call. In the FLUTTER FLIGHT, the displaying male traverses an arc between two perches with a special, slow wing-fluttering pattern, while in the HOVER FLIGHT, the male slowly rises in a hover above his perch or between two perches, often fairly close to the other male. The courtship sequence typically ends abruptly with the territorial male chasing the other male off while making chur calls.

Frequency: Approximately 17 percent of courtship sequences involve a male displaying to another male, and about 5 percent of male visits to territories result in courtship. Although no mountings or attempted copulations between males have been seen, heterosexual matings have rarely been witnessed either. At one study site, for example, only two male-female mountings were observed during more than 560 hours of observation over ten months.

Orientation: It is difficult to determine the relative proportion and "preference" of heterosexual versus homosexual behavior in Ocher-bellied Flycatchers. Some researchers believe that territorial males who court other males do not realize they are displaying to a bird of the same sex, in which case they would be exhibiting superficially heterosexual behavior toward (behaviorally) "transvestite" birds. For the males who approach territorial males, however, the situation is even less clear: many of these are probably floaters who presumably are aware that they are being courted by another male, i.e., they are ostensibly participating in {579}

homosexual activity. However, in at least one case the approaching male was a neighboring territorial male who also displayed to females on his own territory, i.e., his courtship interactions were actually bisexual.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

As noted above, more than half of the male population consists of nonbreeders, since floaters and satellites rarely, if ever, mate heterosexually. Moreover, the absence of breeding activity in these males cannot be attributed to a shortage of available display sites, since more than three-quarters of suitable territories go unused (and nearly a quarter of these are especially prime pieces of "real estate").

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

Sherry, T. W. (1983) "Mionectes oleaginea." In D. H. Janzen, ed., Costa Rican Natural History, pp. 586-87. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Skutch, A. E. (1960) "Oleaginous pipromorpha." In Life Histories of Central American Birds II, Pacific Coast Avifauna no. 34, pp. 561-70. Berkeley: Cooper Ornithological Society.

Snow, B. K., and D. W. Snow (1979) "The Ocher-bellied Flycatcher and the Evolution of Lek Behavior." Condor 81:286-92.

Westcott, D. A. (1997) "Neighbors, Strangers, and Male-Male Aggression as a Determinant of Lek Size." Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 40:235-42.

--- (1993) "Habitat Characteristics of Lek Sites and Their Availability for the Ocher-bellied Flycatcher, Mionectes oleagineus." Biotropica 25:444-51.

--- (1992) "Inter- and Intra-Sexual Selection: The Role of Song in a Lek Mating System." Animal Behavior 44:695-703.

* Westcott, D. A., and J. N. M. Smith (1994) "Behavior and Social Organization During the Breeding Season in Mionectes oleagineus, a Lekking Flycatcher." Condor 96:672-83.

{580}

SWALLOWS, WARBLERS, FINCHES, AND OTHERS

Swallows

Swallows

TREE SWALLOW (Tachycineta bicolor)

IDENTIFICATION: A small to medium-sized swallow with iridescent blue-green upperparts, white underparts, and a tail that is only slightly forked. DISTRIBUTION: Canada and northern United States; winters in southern United States to northwestern South America. HABITAT: Forests, fields, meadows, marshes; usually near water. STUDY AREA: Allendale, Michigan.

Social Organization

Tree Swallows are extremely social birds: outside of the mating season, they gather in large flocks that may contain several hundred thousand individuals, while during the breeding season they form pairs and often nest in aggregations or colonies.

Description

Behavioral Expression: Groups of male Tree Swallows sometimes pursue other males during the mating season in order to copulate with them. When the object of their attentions alights, the males hover in a "cloud" above him, constantly fluttering and making the distinctive tick-tick-tick call that is characteristic of males when they are mating with females. If one of them succeeds in mounting the male, a complete homosexual copulation ensues: the male on top holds on to the other male's neck and back feathers with his bill, while the male being mounted lifts his tail so that genital contact can occur. As in heterosexual mating, multiple, repeated genital contacts may occur during a single copulation between two males, which can last for up to a minute (male-female mounts generally last about 30 seconds). The cluster {581}

of males may also engage in several consecutive episodes of homosexual mating: when the male who was mounted flies off, the group will continue pursuing him until he lands again, and the whole process is repeated.

Frequency: Homosexual copulations have been observed only occasionally in Tree Swallows. However, heterosexual nonmonogamous matings are also rarely seen in this species, yet they are known to be very common because of the high rate of offspring that result from them (see below). Most such copulations therefore probably occur in locations where (or at times when) they are not readily observed. Homosexual matings (which follow the pattern of nonmonogamous copulations) probably also occur more often than they are observed.

Orientation: Some males that participate in homosexual pursuits and copulations are probably bisexual: for example, one male who was mounted by other males was the father of six-day-old nestlings when he participated in homosexual activity. The males mounting him were not paired with female mates in the same nesting colony, however, and may have been nonbreeders (although they could also have been heterosexually paired birds visiting from another colony).

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Heterosexual pairs of Tree Swallows sometimes copulate well before the female is fertile, and nonreproductive matings may also occur after the eggs are laid or even following hatching of chicks. Overall, each pair copulates about 50-70 times per clutch of eggs produced. At least 15 percent of matings also occur after the female's fertile period, and more than 20 percent of mounts do not involve genital contact. In addition, a large number of heterosexual copulations that take place during incubation — as well as throughout the breeding season — are nonmonogamous matings between a female and a male other than her mate. Although many pairs are monogamous in this species (about half of all females are strictly faithful), promiscuous copulations are a prominent feature of Tree Swallow heterosexual interactions. Females often solicit such copulations (sometimes from several different males) and are also able to effectively terminate unwanted promiscuous matings. They do this by flying away, refusing to lift their tail for genital contact, or turning their head and snapping or "chattering" at the male. Nonmonogamous matings frequently result in offspring: in some populations, 50-90 percent of all nests contain young that are not genetically related to their mother's mate, and these constitute 40-75 percent of all nestlings. In some families, all the offspring are fathered by other males. The opposite situation also sometimes occurs: youngsters may be related to the father but not his female partner. This may result from mate-switching (divorce and remating), or because females occasionally lay eggs in another female's nests (5-9 percent of all nests are PARASITIZED this way).

In some populations, 3-8 percent of males form polygamous trios in which they bond and breed with two females simultaneously. If the two females share a nest, one may help care for the other's nestlings if her own eggs do not hatch. Many {582}

populations also have large numbers of nonbreeding birds, sometimes called FLOATERS because they do not occupy their own territories and tend to travel widely. As many as a quarter of all reproductively mature females are floaters. In addition to helping raise unrelated birds of their own species, Tree Swallows sometimes "adopt" nests belonging to other birds such as purple martins (Progne subis) or bluebirds (Sialia spp.), raising the foster young in addition to their own. More than half of all Tree Swallow heterosexual pairs do not remain together for more than one breeding season. Single parenting also occasionally occurs in this species, for example if one parent is killed or dies during the breeding season. Frequently, however, the widowed parent re-pairs with another mate. If a single parent is laying or incubating eggs, its new mate often adopts the brood, but if a single parent already has nestlings from the previous mate, the new partner often kills them (usually by pecking) in order to begin breeding himself or herself. Infanticide also sometimes occurs when a female kills a paired female's nestlings in order to try to precipitate a divorce and mate with her partner.

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

Barber, C. A., R. J. Robertson, and P. T. Boag (1996) "The High Frequency of Extra-Pair Paternity in Tree Swallows Is Not an Artifact of Nestboxes." Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 38:425-30.

Chek, A. A., and R. J. Robertson (1991) "Infanticide in Female Tree Swallows: A Role for Sexual Selection." Condor 93:454-57.

Dunn, P. O., and R. J. Robertson (1992) "Geographic Variation in the Importance of Male Parental Care and Mating Systems in Tree Swallows." Behavioral Ecology 3:291-99.

Dunn, P. O., and R. J. Robertson, D. Michaud-Freeman, and P. T. Boag (1994) "Extra-Pair Paternity in Tree Swallows: Why Do Females Mate with More than One Male?" Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 35:273-81.

Leffelaar, D., and R. J. Robertson (1985) "Nest Usurpation and Female Competition for Breeding Opportunities by Tree Swallows." Wilson Bulletin 97:221-24

--- (1984) "Do Male Tree Swallows Guard Their Mates?" Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 16:73-79.

Lifjeld, J. T., P. O. Dunn, R. J. Robertson, and P. T. Boag (1993) "Extra-Pair Paternity in Monogamous Tree Swallows." Animal Behavior 45:213-29.

Lifjeld, J. T., and R. J. Robertson (1992) "Female Control of Extra-Pair Fertilization in Tree Swallows." Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 31:89-96.

* Lombardo, M. P. (1996) Personal communication.

--- (1988) "Evidence of Intraspecific Brood Parasitism in the Tree Swallow." Wilson Bulletin 100:126-28.

--- (1986) "Extrapair Copulations in the Tree Swallow." Wilson Bulletin 98:150-52.

* Lombardo, M. P., R. M. Bosman, C. A. Faro, S. G. Houtteman, and T.S. Kluisza (1994) "Homosexual Copulations by Male Tree Swallows." Wilson Bulletin 106:555-57.

Morrill, S. B., and R. J. Robertson (1990) "Occurrence of Extra-Pair Copulation in the Tree Swallow (Tachycineta bicolor)." Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 26:291-96.

Quinney, T. E. (1983) "Tree Swallows Cross a Polygyny Threshold." Auk 100:750-54.

Rendell, W. B. (1992) "Peculiar Behavior of a Subadult Female Tree Swallow." Wilson Bulletin 104:756-59.

Robertson, R. J. (1990) "Tactics and Counter-Tactics of Sexually Selected Infanticide in Tree Swallows." In J. Blondel, A. Gosler, J.-D. Lebreton, and R. McCleery, eds., Population Biology of Passerine Birds: An Integrated Approach, pp. 381-90. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Robertson, R. J., B. J. Stutchbury, and R. R. Cohen (1992) "Tree Swallow (Tachycineta bicolor)." In A. Poole, P. Stettenheim, and F. Gill, eds., The Birds of North America: Life Histories for the 21st Century, no. 11. Philadelphia: Academy of Natural Sciences; Washington, D.C.: American Ornithologists' Union.

Stutchbury, B. J., and R. J. Robertson (1987a) "Signaling Subordinate and Female Status: Two Hypotheses for the Adaptive Significance of Subadult Plumage in Female Tree Swallows." Auk 104:717-23. {583}

--- (1987b) "Behavioral Tactics of Subadult Female Floaters in the Tree Swallow." Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 20:413-19.

--- (1987c) "Two Methods of Sexing Adult Tree Swallows Before They Begin Breeding." Journal of Field Ornithology 58:236-42.

--- (1985) "Floating Populations of Female Tree Swallows." Auk 102:651-54.

Venier, L. A., P. O. Dunn, J. T. Lifjeld, and R. J. Robertson (1993) "Behavioral Patterns of Extra-Pair Copulation in Tree Swallows." Animal Behavior 45:412-15.

Venier, L. A., and R. J. Robertson (1991) "Copulation Behavior of the Tree Swallow, Tachycineta bicolor: Paternity Assurance in the Presence of Sperm Competition." Animal Behavior 42:939-48.

Swallows

Swallows

CLIFF SWALLOW (Hirundo pyrrhonota)

IDENTIFICATION: A bluish brown swallow with pale underparts, buff forehead, and a chestnut throat; tail is not forked. DISTRIBUTION: North and Central America; winters in southern South America. HABITAT: Open country, cliffs. STUDY AREAS: Near Jackson Hole (Moran), Wyoming, Lakeview, Kansas, and along the North and South Platte Rivers, Nebraska; subspecies H.p. hypopolia and H.p. pyrrhonota.

BANK SWALLOW (Riparia riparia)

IDENTIFICATION: A small, sparrow-sized swallow with a slightly forked tail, brown plumage, white underparts, and a brown breast band. DISTRIBUTION: Throughout North America and Eurasia; winters to South America and southern Africa. HABITAT: Open country near water. STUDY AREAS: Near Madison, Wisconsin, and Dunblane, Scotland; subspecies

R.r. riparia.

Social Organization

Cliff and Bank Swallows are highly gregarious and may flock by the hundreds or even thousands. They generally form mated pairs (although many alternative arrangements also occur, see below) and nest in colonies. Cliff Swallow colonies are the largest of any swallow in the world, often containing a thousand nests (and sometimes up to three times this number).

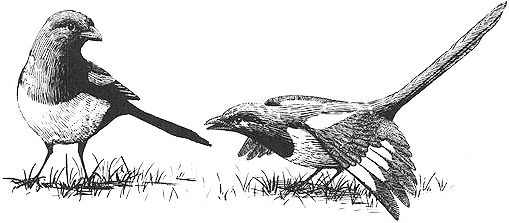

A male Cliff Swallow mounting another male (right) and attempting to copulate with him during a mud-gathering session

{584}

Description

Behavioral Expression: Male Cliff and Bank Swallows often try to copulate with both males and females that are not their own mates. Unlike in Tree Swallows, these are usually forced copulations or "rapes," since the bird being pursued — whether male or female — does not welcome the sexual advances of the male. Homosexual copulation attempts in Cliff Swallows take place on the ground at social gatherings of birds that are sunning themselves or gathering mud or grass for nests. Anywhere from a handful to several hundred individuals may be present at a time, although such groups usually contain 10-30 birds. At mud-gathering sessions, one male pounces on another male from above, landing on his back and often grabbing his head or neck feathers in his beak. At sunning sites, the male usually lands a few inches away from the other bird and makes threatening HEAD-FORWARD displays prior to jumping on his back. Once mounted, he spreads his tail and moves it sideways, trying to make cloacal (genital) contact, all the while vigorously flapping his wings; the other male usually strongly resists, and sometimes a fight ensues, before both birds fly off. The entire copulation attempt is usually quite brief, though it can last for up to 10 seconds (a relatively long duration for bird mountings). Forcible mountings of females follow this same pattern. When on the ground at mud-gathering sites, birds of both sexes typically flutter their wings above their backs to try to prevent males from mounting them.

Male Bank Swallows also pursue both females and males to try to copulate with them. Males first make many INVESTIGATORY CHASES of unfamiliar birds to determine if they are worth following. If they find a bird they are interested in — which may be another male — a full-fledged SEXUAL CHASE ensues, sometimes drawing several birds into the pursuit as well. Often the targeted bird is able to get away, but sometimes the chase ends with a forced copulation attempt. Homosexual mountings also occur when birds congregate on the ground, for instance to gather nest materials or dust themselves. At times, a veritable "orgy" develops as numerous males frantically try to mount birds of both sexes. Sometimes one or two males will even mount a third male who is already copulating with another bird.

{585}

Frequency: In Bank Swallows, 8 percent of sexual chases are homosexual, while 36-40 percent of investigatory chases involve males pursuing other males. Cliff Swallow rape attempts are extremely common, occurring every two to three minutes at some mud-gathering sites; one male may attempt to mount six to eight different birds in a five-to-ten-minute period. These mounts are probably fairly evenly distributed between males and females, although homosexual mounts may in fact occur more often. When presented with stuffed birds of both sexes in identical poses, male Cliff Swallows mounted other males nearly 65 percent of the time.

Orientation: Most, if not all, male Cliff and Bank Swallows that pursue copulations with other males also try to forcibly mount females, and to this extent they are bisexual. However, in Cliff Swallows only a few males appear to engage in such behavior with either males or females. Many of these are unpaired birds, although males who are already heterosexually paired (including fathers) also sometimes participate in promiscuous copulations.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Heterosexual social life in Cliff and Bank Swallows is replete with behaviors that deviate from the monogamous-pair/nuclear-family model. As discussed above, a large proportion of heterosexually mated Swallows seek copulations with birds other than their partner, and considerable evidence suggests that these mounting attempts are nonprocreative. Because of the resistance of the bird being mounted, the copulation is often not completed and sperm is rarely transferred. In addition, such attempts may also occur outside the breeding season when there is no possibility of fertilization. Genetic studies have shown that probably only 2-6 percent of Cliff Swallow nests have young that might result from nonmonogamous sexual activity. However, nearly a quarter of all nestlings, in more than half of all nests, are raised by birds other than their biological mother and/or father. This is because Cliff Swallows participate in an extraordinary array of activities that serve to exchange eggs and nestlings between families. For example, as many as 43 percent of all nests contain an egg laid by an outside female — this bird usually has her own nest, but she also PARASITIZES or adds eggs to other nests (and often has eggs added to her own as well). In some cases, this female may even return to the foreign nest to incubate the entire clutch (even though only one egg is hers), but she does not help raise the nestlings once they hatch. Often the intruding female's mate will destroy or toss out eggs in the host nest to make room for their own (up to 20 percent of all nests may suffer egg destruction). In other cases, males appear to destroy eggs in other nests so as to keep the laying female sexually receptive, thereby increasing the opportunities for heterosexual nonmonogamous matings. Birds also occasionally physically carry eggs from their own nest to another — about 6 percent of all nests contain eggs transferred this way. Finally, in a few cases Swallows have even been seen transferring actual baby birds between nests. Infanticide may also occur when birds attack and toss nestlings out of neighbors' nests. In both species, young birds gather into large

CRÈCHES or "day-care {586}

centers" — sometimes containing up to a thousand youngsters — which give them protection while their parents are away searching for food.

Divorce and single parenting also occur in Bank Swallows: females sometimes desert their mates to start a new family with another male, forcing their first mate to raise the nestlings on his own. In addition to the rape attempts described above, there is considerable aggression between the sexes as well. Ironically, male Bank Swallows often become violent toward their own female partners when trying to protect them from the advances of other males. Sometimes they knock their mate to the ground, fighting her directly, or try to force her back into their burrow. Nonreproductive sexual behaviors are also prevalent in these two species. Besides copulations outside the breeding season and group sexual activity (mentioned above), members of a Cliff Swallow pair often copulate at a rate far in excess of that needed simply to fertilize their eggs. In addition, males of both species have occasionally been seen trying to mate with dead birds, as well as with other species such as barn swallows (Hirundo rustica) and Tree Swallows.

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

* Barlow, J. C., E. E. Klaas, and J. L. Lenz (1963) "Sunning of Bank Swallows and Cliff Swallows." Condor 65:438-48.

Beecher, M. D., and 1. M. Beecher (1979) "Sociobiology of Bank Swallows: Reproductive Strategy of the Male." Science 205:1282-85.

Beecher, M. D., I. M. Beecher, and S. Lumpkin (1981) "Parent-Offspring Recognition in Bank Swallows (Riparia riparia): I. Natural History." Animal Behavior 29:86-94.

Brewster, W. (1898) "Revival of the Sexual Passion in Birds in Autumn." Auk 15:194-95.

* Brown, C. R., and M.B. Brown (1996) Coloniality in the Cliff Swallow: The Effect of Group Size on Social Behavior. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

* --- (1995) "Cliff Swallow (Hirundo pyrrhonota)." In A. Poole and F. Gill, eds., The Birds of North America: Life Histories for the 21st Century, no. 149. Philadelphia: Academy of Natural Sciences; Washington, D.C.: American Ornithologists' Union.

--- (1989) "Behavioral Dynamics of Intraspecific Brood Parasitism in Colonial Cliff Swallows." Animal Behavior 37:777-96.

--- (1988a) "A New Form of Reproductive Parasitism in Cliff Swallows." Nature 331:66-68.

--- (1988b) "The Costs and Benefits of Egg Destruction by Conspecifics in Colonial Cliff Swallows." Auk 105:737-48.

--- (1988c) "Genetic Evidence of Multiple Parentage in Broods of Cliff Swallows." Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 23:379-87.

Butler, R. W. (1982) "Wing-fluttering by Mud-gathering Cliff Swallows: Avoidance of 'Rape' Attempts?" Auk 99:758-61.

* Carr, D. (1968) "Behavior of Sand Martins on the Ground." British Birds 61:416-17.

Cowley, E. (1983) "Multi-Brooding and Mate Infidelity in the Sand Martin." Bird Study 30:1-7.

* Emlen, J. T., Jr. (1954) "Territory, Nest Building, and Pair Formation in Cliff Swallows." Auk 71:16-35.

--- (1952) "Social Behavior in Nesting Cliff Swallows." Condor 54:177-99.

Hoogland, J. L., and P. W. Sherman (1976) "Advantages and Disadvantages of Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia) Coloniality." Ecological Monographs 46:33-58.

* Jones, G. (1986) "Sexual Chases in Sand Martins (Riparia riparia): Cues for Males to Increase Their Reproductive Success." Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 19:179-85.

* Petersen, A. J. (1955) "The Breeding Cycle in the Bank Swallow." Wilson Bulletin 67:235-86.

Thom, A. S. (1947) "Display of Sand-Martin." British Birds 40:20-21.

{587}

Wood Warblers

Wood Warblers

HOODED WARBLER (Wilsonia citrina)

IDENTIFICATION: A small songbird with bright yellow underparts, olive green upperparts, and a black crown ("hood") and throat in adult males and some females (see below). DISTRIBUTION: Eastern North America; winters in Mexico and Central America. HABITAT: Deciduous forests, cypress swamps. STUDY AREA: Smithsonian Environmental Research Center near Annapolis, Maryland.

Social Organization

During the breeding season, male Hooded Warblers establish and defend territories, attracting mates with whom they usually form pair-bonds. Outside of the mating season, birds migrate south to their winter homes, where the two sexes live largely separate from each other.

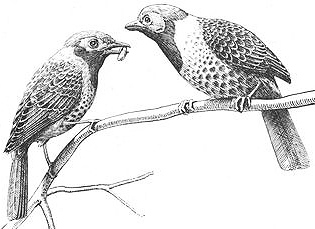

A pair of male Hooded Warblers tending their chicks

Description

Behavioral Expression: Male Hooded Warblers occasionally form homosexual pairs and become joint parents. Same-sex pair-bonds develop early in the mating season when one male is attracted to another male's territory by his singing. In some cases, this is a male he has previously "prospected" on a visit to his territory during the prior mating season. Once a pair-bond is established, the males focus their attentions on parenting duties. Homosexual couples acquire nests and eggs in a variety of ways. Some pairs may build their own nests: although male Hooded Warblers in heterosexual pairs rarely build nests, at least one bird in a homosexual pair was observed carrying grass fibers to a nest and shaping the cup by repeatedly sitting in the nest and shifting his position. It is not known, however, whether he had built the nest or was simply adding material to a nest built by another pair. As for eggs, some pairs incubate eggs laid by another species of bird, the Brown-headed Cowbird. This species is known as a PARASITE because it always lays its eggs in the nests of other birds, "forcing" them to raise its young. Hooded Warblers are particularly susceptible to parasitism by Cowbirds: in some populations, three-quarters of all nests are parasitized, and Cowbirds appear to prefer Hooded Warbler nests over those of other species. Cowbirds occasionally lay eggs in completely empty nests, so some homosexual pairs of Hooded Warblers may build their own {588}

nest and end up tending only Cowbird eggs. Usually, though, a Cowbird adds its egg(s) to a nest that already has eggs (often removing part of the original clutch). Sometimes a Hooded Warbler mother abandons her nest once it has been disturbed this way, and some homosexual pairs may "adopt" such abandoned nests, or else the father of such a nest may re-pair with a male following the mother's abandonment. At least two male pairs have been observed tending nests that were parasitized, since they each contained both Cowbird and Hooded Warbler chicks. Other male couples probably adopt nests that have been abandoned after attacks by predators. Bluejays and squirrels often prey on Hooded Warbler nestlings, and usually their mother will abandon the entire nest even if only one youngster has been taken. Finally, some homosexual pairs may tend eggs that have been directly laid in their nest by a female Hooded Warbler. In many bird species, females lay eggs in nests belonging to other birds of the same species (this is another form of parasitism); although this rarely occurs in Hooded Warblers, it is a possible source of eggs for homosexual pairs.

Once they have acquired a nestful of eggs, male couples typically divide up the parenting duties: one attends to nest repair, incubation of the eggs, and brooding of the nestlings, while the other feeds his mate and defends the territory. Both birds feed the nestlings insects such as crane flies. Although this division of labor is similar to that in heterosexual pairs — females typically build nests and incubate, males defend territories, and both feed nestlings — there are crucial differences. In homosexual pairs, incubating males are often fed by their mate, which occurs only rarely in heterosexual pairs. In addition, one male who engaged in typically "female" parental duties was later observed performing territorial singing (albeit with a song pattern that differed from that of most other males). Nests belonging to homosexual pairs are often lost entirely to predators, but up to 50 percent or more of all heterosexual nests are lost in the same way. The male couples that have been followed over a longer time do not appear to re-pair with the same mate in subsequent breeding seasons; their divorces may be related to the loss of nests to predators. Heterosexual divorce is also common in Hooded Warblers, with as many as half of all male-female pairs failing to remain together, perhaps also due in large part to loss of nests. It is possible as well that divorce is simply a general feature of {589}

pair-bonding in this species (heterosexual or homosexual) independent of nest losses, or that the particular pairs being studied happened to end in divorce without this being indicative of a larger pattern.

Some female Hooded Warblers are transvestite, having the same black hood that males do. In fact there is a continuum of transgendered physical appearance in females: some have no black feathers on their head at all, some have an intermediate amount with a black "bib" around the throat, while others are almost indistinguishable from males. In addition, a few females can sing (typically only males in this species are able to sing). Transgendered females usually mate with males and raise young just like nontransgendered females.

Transgendered Hooded Warblers: females of this species usually have little or no black on their heads (far left), but some individuals are plumage transvestites, exhibiting a full malelike black hood and chin strap (far right).

Other females exhibit a gradation of plumage patterns that fall between these two extremes (center).

Frequency: The overall incidence of homosexual pairs in Hooded Warblers is not known, since no widespread, systematic study has yet been conducted to determine their prevalence. However, in one population observed over three years, 4 percent of the pair-bonds (3 of 80) were between males. Although overt sexual behavior has not yet been observed between such pair-mates, heterosexual copulations (both within-pair and nonmongamous) are rarely seen in this species either; it is possible, therefore, that homosexual copulations do take place. Among females, plumage transvestism is a regular occurrence, as about 59 percent of females have some degree of malelike black feathers on their head: 40 percent have only a slight amount, 17 percent an intermediate amount, and 2 percent have a nearly complete black hood.

Orientation: Some male Hooded Warblers appear to be exclusively homosexual, pairing only with males; if they divorce a male partner, they re-pair with another male in subsequent breeding seasons. These males often perform parenting duties typically associated with females in heterosexual pairs. Other males, however, are bisexual, alternating between homosexual pairings and heterosexual ones in different breeding seasons.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

As mentioned above, heterosexual divorce is common in Hooded Warblers, as are a number of other variations on the nuclear family and monogamous pair-bond. About 4 percent of males form trios, mating with two females who both nest simultaneously on the male's territory; 6 percent of males are nonbreeders, and some females remain single as well. Among paired birds, promiscuous copulations also occur very frequently: 30-50 percent of all females copulate with males other than their mates (usually neighboring males), and more than a third of all nestlings in some populations are fathered by a bird other than their mother's mate. In addition, males sometimes adopt young birds from neighboring families whose own parents have finished caring for them; adoptive fathers typically feed these youngsters along with their own nestlings. The adopted birds are usually not genetically related to their foster fathers, i.e., they are not the result of promiscuous matings by the bird who adopts them. Single parenting is also a regular occurrence in Hooded {590}

Warblers: once their young can fly, parents usually separate and each takes care of half the brood (unless the female begins a second family, in which case the male will assume responsibility for all of the youngsters). In fact, single parenting is generally more extensive and longer-lasting than male-female coparenting in this species. Nestlings receive biparental care for only eight or nine days, while single parenting can last for three to six weeks and involves feeding rates that are three to five times higher than that of coparents. As a result of separation of mated pairs, males and females are together for only about one month out of the entire year. During the winter, the two sexes occupy largely segregated habitats, with males preferring forests and females scrub areas.

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

Evans Ogden, L. J., and B. J. Stutchbury (1997) "Fledgling Care and Male Parental Effort in the Hooded Warbler (Wilsonia citrina)." Canadian Journal of Zoology 75:576-81.

--- (1994) "Hooded Warbler (Wilsonia citrina):" In A. Poole and F. Gill, eds., The Birds of North America: Life Histories for the 21st Century, no. 110. Philadelphia: Academy of Natural Sciences; Washington, D.C.: American Ornithologists' Union.

Godard, R. (1993) "Tit for Tat Among Neighboring Hooded Warblers." Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 33:45-50.

--- (1986) "Long-Term Memory of Individual Neighbors in a Migratory Songbird." Nature 350:228-29.

* Lynch, J. F., E. S. Morton, and M. E. Van der Voort (1985) "Habitat Segregation Between the Sexes of Wintering Hooded Warblers (Wilsonia citrina)." Auk 102:714-21.

* Morton, E. S. (1989) "Female Hooded Warbler Plumage Does Not Become More Male-Like With Age." Wilson Bulletin 101:460-62.

* Niven, D. K. (1997) Personal communication.

* --- (1993) "Male-Male Nesting Behavior in Hooded Warblers." Wilson Bulletin 105:190-93.

Stutchbury, B. J. M. (1998) "Extra-Pair Mating Effort of Male Hooded Warblers, Wilsonia citrina." Animal Behavior 55:553-61.

* --- (1994) "Competition for Winter Territories in a Neotropical Migrant: The Role of Age, Sex, and Color." Auk 111:63-69.

Stutchbury, B. J., and L. J. Evans Ogden (1996) "Fledgling Adoption in Hooded Warblers (Wilsonia citrina): Does Extrapair Paternity Play a Role?" Auk 113:218-20.

* Stutchbury, B. J., and J. S. Howlett (1995) "Does Male-Like Coloration of Female Hooded Warblers Increase Nest Predation?" Condor 97:559-64.

Stutchbury, B. J., J. M. Rhymer, and E. S. Morton (1994) "Extrapair Paternity in Hooded Warblers." Behavioral Ecology 5:384-92.

{591}

Finches

Finches

CHAFFINCH (Fringilla coelebs)

IDENTIFICATION: A sparrow-sized bird with olive-brown plumage, distinctive white shoulder bars, and (in males) blue-gray crown. DISTRIBUTION: Europe, Siberia, central Asia, North Africa. HABITAT: Forest, farmland. STUDY AREAS: Ylivieska, Finland; near Cambridge, England; subspecies F.c. coelebs and F.c. gengleri.

SCOTTISH CROSSBILL (Loxia scotica)

IDENTIFICATION: A sparrow-sized bird with olive to orange-red plumage and a distinctive crossed bill. DISTRIBUTION: Northern Scotland. HABITAT: Coniferous forest. STUDY AREAS: Speyside and Sutherland, Scotland.

Social Organization

Chaffinches and Scottish Crossbills commonly associate in flocks; the mating system involves (usually monogamous) pair-bonding.

Description

Behavioral Expression: Female Chaffinches sometimes form homosexual pair-bonds with each other. In this species, usually only males sing; however, in same-sex pairs, one female partner typically sings much in the manner of a male, throwing back her head while perched conspicuously in the trees (this is probably how she attracts her female mate). Her song resembles that of males in duration, loudness, and structure, consisting of a long stream of rapidly trilled notes of descending pitch, finished off with a staccato end phrase or "flourish." It differs from male song, however, in having not quite as ringing a tone. Like male Chaffinches, she may even COUNTERSING in response to a neighboring male's song, the two birds "replying" to each other with alternating or syncopated song phrases. Females in same-sex pairs may also try to sing together, although one partner may only be able to produce an incomplete version of the song. The two females behave like other mated couples, and may even engage in courtship pursuits known as SEXUAL CHASES. In this activity — which is a demonstration of sexual interest — one female zigzags after her partner using a special form of flying known as MOTH FLIGHT (rapid, shallow wingbeats without the pauses or undulating quality typical of regular flight). Occasionally, juvenile males pursue other males in such sexual chases. {592}

Homosexual couples also occur in Scottish Crossbills — but among males. A male attracts potential mates by singing high in a treetop, advertising his presence with a loud stream of notes transcribed as chip-chip-chip-gee-gee-gee chip-chip-chip. Most singing males respond aggressively to other males who enter their territory, but occasionally the displaying male does not chase away another male that is attracted to him. The two males may then pair up and associate in much the same way that heterosexual couples do, except that copulation has not been observed between male partners. They synchronize their movements, traveling together between forest clumps, sometimes one leading the other. Occasionally, two neighboring males who are each heterosexually mated become companions. The two forage together and jointly defend clumps of pine trees (their principal food source) while still maintaining their opposite-sex bonds. The two males may even visit their female mates together, attending first to one and then the other, with one male feeding his female partner while his male companion waits for him.

Frequency: In both of these species, homosexual pairs are probably only an occasional occurrence. Although no statistics concerning the incidence of same-sex pairing are available, in Chaffinches about 1 in 150 nests contains a SUPERNORMAL CLUTCH of 7-8 eggs. In many species such larger-than-average clutches are laid by female pairs, and this may also be true in Chaffinches (although their specific association with same-sex pairing has not yet been demonstrated).

Orientation: Individual Chaffinches or Scottish Crossbills who form same-sex associations have not been tracked throughout their entire lives to determine if they only pair with members of the same sex. However, since heterosexual pairs in these species are usually lifelong, it is not unlikely that homosexual pairs would be as well. In addition, some Scottish Crossbill males are bisexual, forming bonds with both males and females simultaneously.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

A variety of nonprocreative heterosexual behaviors are found in Chaffinches and Scottish Crossbills. Chaffinch couples sometimes copulate during incubation (i.e., after fertilization has occurred), and only 40-50 percent of all matings during the fertilizable period involve full genital contact. Some pairs may attempt to mate more than 200 times for each clutch of eggs they produce, as often as 4 times an hour. Mounts are often not completed for a variety of reasons: the male may slip off the female's back or mount in a reversed head-to-tail position, or (more commonly) either partner may flee from the other out of fear or because of provocation from its mate. In fact, heterosexual courtship and mating in this species often entails a considerable amount of aggressive behavior between the sexes. Many birds do not participate in breeding at all: there are surplus flocks of single birds in many populations (males in Scottish Crossbills, both sexes in Chaffinches), as well as nonbreeding pairs in Scottish Crossbills. Interestingly, outside of the breeding season sexual segregation is also the rule. Males and female tend to migrate separately {593}

(wintering flocks are often same-sex), and females generally travel farther than males, often resulting in local populations with more males than females. In fact, this phenomenon has lent the Chaffinch its scientific name: coelebs means "bachelor" in Latin.

Scottish Crossbills frequently engage in "symbolic" matings early in the breeding season, in which the male mounts the female but no genital contact occurs. Sometimes these mounts are promiscuous: several males other than the female's mate may participate. Nonmonogamous matings are also fairly common in Chaffinches, often between neighboring birds. About 8 percent of all mating activity involves nonmates, and 17 percent of all offspring (in a quarter of all broods) result from such copulations. Occasionally, a pair will separate or "divorce" during the breeding season, after which the single female may copulate with several already paired males. Eventually, a polygamous trio may develop if one of these males forms a pair-bond with her in addition to his own mate. Some Scottish Crossbills are also polygamous, forming trios of one male with two females. In this species, parents (in monogamous pairs) regularly become single parents: they separate when their young are able to fly, dividing the young between them and raising them on their own. Because the mother and father often travel to widely separated feeding grounds, youngsters belonging to the same family may be raised in very different environments. Occasionally, unrelated birds — both males and females — help feed and "foster-parent" the young birds after their biological parents have separated.

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

Adkisson, C. S. (1996) "Red Crossbill (Loxia curvirostra)." In A. Poole, P. Stettenheim, and F. Gill, eds., The Birds of North America: Life Histories for the 21st Century, no. 256. Philadelphia: Academy of Natural Sciences; Washington, D.C.: American Ornithologists' Union.

Halliday, H. (1948) "Song of Female Chaffinch." British Birds 41:343-44.

Hanski, I. K. (1994) "Timing of Copulations and Mate Guarding in the Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs." Ornis Fennica 71:17-25.

Kling, J. W., and J. Stevenson-Hinde (1977) "Development of Song and Reinforcing Effects of Song in Female Chaffinches." Animal Behavior 25:215-20.

Knox, A. G. (1990) "The Sympatric Breeding of Common and Scottish Crossbills Loxia curvirostra and L. scotica and the Evolution of Crossbills." Ibis 132:459-66.

* Marjakangas, A. (1981) "A Singing Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs in Female Plumage Paired with Another Female-Plumaged Chaffinch." Ornis Fennica 58:90-91.

* Marler, P. (1956) Behavior of the Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs. Behavior Supplement V. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

--- (1955) "Studies of Fighting in Chaffinches. 2. The Effect on Dominance Relations of Disguising Females as Males." British Journal of Animal Behavior 3:137-46.

* Nethersole-Thompson, D. (1975) Pine Crossbills: A Scottish Contribution. Berkhamsted: T. and A. D. Poyser.

Sheldon, B. C. (1994) "Sperm Competition in the Chaffinch: The Role of the Female." Animal Behavior 47:163-73.

Sheldon, B. C., and T. Burke (1994) "Copulation Behavior and Paternity in the Chaffinch." Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 34:149-56.

Svensson, B. V. (1978) "Clutch Dimensions and Aspects of the Breeding Strategy of the Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs in Northern Europe: A Study Based on Egg Collections." Ornis Scandinavica 9:66-83.

Voous, K. H. (1978) "The Scottish Crossbill Loxia scotica." British Birds 71:3-10.

{594}

Shrikes, Tits, and Bluebirds

Shrikes, Tits, and Bluebirds

RED-BACKED SHRIKE (Lanius collurio)

IDENTIFICATION: A small (6 1/2 inch) bird with a thick, hooked bill, grayish brown plumage, and a darker facial mask (black in males). DISTRIBUTION: Throughout Eurasia and northeast Africa; winters to southern Africa. NABITAT: Savanna, woodland, scrub, farmland. STUDY AREA: New Forest, Hampshire, England.

BLUE TIT (Parus caeruleus)

IDENTIFICATION: A tiny (4 1/2 inch) chickadee-like bird with a bright blue crown, black-and-white face, bluish green plumage, and yellow underparts. DISTRIBUTION: Europe, Middle East, North Africa. HABITAT: Woodland, human habitation. STUDY AREA: Marley Wood, Oxfordshire, England; subspecies P.c. obscurus.

EASTERN BLUEBIRD (Sialia sialis)

IDENTIFICATION: A sparrow-sized bird with bright blue plumage, white underparts, and a chestnut throat and breast. DISTRIBUTION: North and Central America. HABITAT: Open woodland, orchards, farmland, pine savanna. STUDY AREA: In the town of Washington, Michigan.

Social Organization

Red-backed Shrikes generally establish monogamous pair-bonds during the mating season and occupy partially overlapping territories. Outside of the breeding season, the birds are more solitary, and males and females typically occupy segregated habitats (males in more open bush country, females in more dense woodland). Blue Tits and Eastern Bluebirds are also territorial and form pair-bonds, but may associate in flocks outside of the breeding season.

A nesting pair of female Red-backed Shrikes in England simultaneously incubating their eggs

Description

Behavioral Expression: In Red-backed Shrikes and Blue Tits, two females sometimes pair with each other, build a nest, and lay eggs. Both partners in Red-backed Shrike homosexual pairs take turns incubating the eggs (in heterosexual pairs, only the female incubates). Sometimes they even sit on the nest together, side by side or one partially covering the other. Both females also lay eggs: as a result, {595}

their nests have SUPERNORMAL CLUTCHES of 9-12 eggs, twice the number in most nests belonging to heterosexual pairs. If their nest is robbed by predators, the pair will dutifully build a second one (often in a much higher location, to make it inaccessible to most ground predators) and begin laying eggs again (as do male-female pairs when they lose a nest). However, all of the eggs they lay are typically infertile since neither female has mated with a male, and the pair usually abandons the nest after the eggs have failed to hatch. Blue Tit female pairs are unlike most homosexual pairs in birds because only one female lays eggs. As a result, nests belonging to such pairs contain not supernormal clutches, but exceptionally small clutches of 3 or so eggs (nests of male-female pairs typically contain about 11 eggs). Both females incubate the eggs simultaneously, sitting together on the nest facing in the same direction. As in Red-backed Shrike homosexual pairs, the eggs are usually infertile and the pair eventually abandons the nest.

In Eastern Bluebirds, two males sometimes associate with one another in what appears to be a homosexual pair-bond: they travel exclusively in each other's company (perhaps even spending the winter together), jointly inspect nest sites during the early spring, and court one another. The latter activity involves COURTSHIP-FEEDING — a behavior also seen in heterosexual pairs — in which one male offers a symbolic food gift, such as a cutworm, to the other male, often preceded by a distinctive call. Paired males might be related to each other (father-son or brothers). Occasionally, a female who has lost her heterosexual mate is joined by another female, who helps coparent her offspring. The two birds take turns feeding the youngsters and may also be assisted by one or more of their young from a previous brood.

Nests belonging to homosexual pairs of Black-winged Stilts (left) and Red-backed Shrikes (right). Both females in the pair lay eggs, and therefore their nests contain "supernormal clutches" (double the usual number of eggs). Because neither female has mated with males, however, these clutches typically consist entirely of unfertilized eggs.

Frequency: Same-sex pairs probably occur only sporadically in these three species: in Red-backed Shrikes, for example, female couples account for perhaps no more than 1 percent of all pairs.

Orientation: Female Red-backed Shrikes and Blue Tits are probably exclusively homosexual, at least for the time that they remain paired with their female partner, since they invariably lay eggs that are infertile (indicating no mating with males). Whether such birds ever subsequently form or have previously formed heterosexual pair-bonds is not known.

{596}

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities