<<< >>>

{621}

Other Birds

FLIGHTLESS BIRDS

Ratites

Ratites

OSTRICH (Struthio camelus)

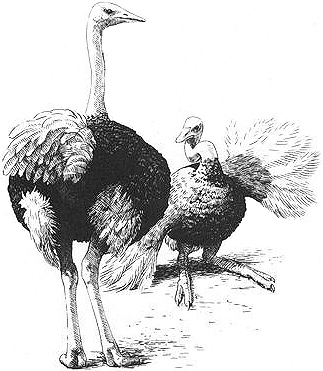

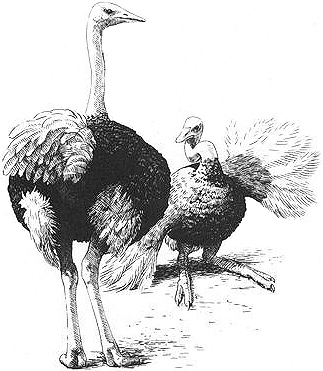

IDENTIFICATION: The largest living bird (over 6 feet tall), with striking black-and-white plumage in the male and powerful legs and claws. DISTRIBUTION: Southern, eastern, and west-central Africa. HABITAT: Open savanna, dry veld, steppe, semidesert. STUDY AREA: Namib Game Reserve, Namibia; subspecies S.c. australis, the South African Ostrich.

EMU (Dromaius novaehollandiae)

IDENTIFICATION: The second-largest living bird (5-6 feet tall), with shaggy, brown plumage and bare patches of blue skin on the face and neck. DISTRIBUTION: Australia. HABITAT: Arid plains, semidesert, scrub, open woodland. STUDY AREAS: Barcoo River and Alice Downs areas, Central Queensland, Australia; Division of Wildlife Research, Helena Valley, Western Australia; Berlin Zoo and Melbourne Zoological Gardens.

GREATER RHEA (Rhea americana)

IDENTIFICATION: Similar to Ostrich but smaller (up to 4 1/2 feet tall) and with overall grayish brown plumage in both sexes. DISTRIBUTION: Southeastern South America. HABITAT: Open brush, grassland, plains. STUDY AREA: Near General Lavalle, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina; subspecies

R.a. albescens.

{622}

Social Organization

Ostriches associate in flocks and frequently form sex-segregated groups. All-male flocks may contain up to 40 individuals, many of them juveniles, who travel with each other for long periods. Emus generally associate in pairs or groups of 3-10 birds, while Greater Rheas gather in flocks of 15-40 birds outside of the mating season. All three species have a wide variety of mating systems (discussed below). These are notable for their various forms of POLYANDRY (females mating with several males) and the fact that — in Emus and Greater Rheas — all incubation and chick-rearing is performed by males without any help from females.

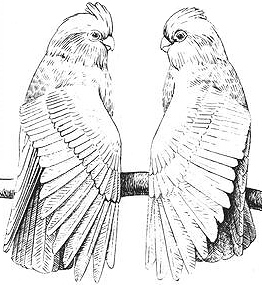

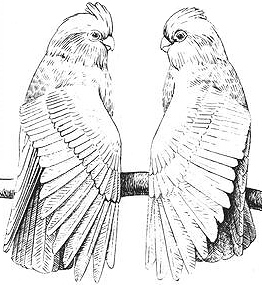

A male Ostrich (right, on the ground) courting another male with the "kantling" display

Description

Behavioral Expression: Male Ostriches perform a homosexual courtship dance to each other that is distinct from heterosexual interactions. Same-sex courtships consist of a sequence of three activities, performed by sexually mature adult males in full nuptial plumage (black-and-white feathers, with a red flush on the face and legs). First, there is a dramatic APPROACH in which one male runs rapidly toward his chosen partner — often achieving speeds of 25-30 mph — and stops abruptly just short of the other male. Then he launches into frenzied PIROUETTE DANCING, a high-speed, energetic circling in place beside his partner. This whirling may occur in a series of bursts, each lasting for several minutes. Finally, in KANTLING, the male drops to the ground next to his partner and rocks steadily from side to side, fluffing out his tail and sweeping the ground with his wings in an exaggerated fashion. All the while, he twists his head and neck in a continuous corkscrew action and repeatedly inflates and deflates his throat. The male being displayed to may acknowledge the dance with his posture, or he may simply maintain a calm stance devoid of alarm or aggression. Homosexual courtships are distinct from heterosexual ones in a number of respects: neither the running approach nor pirouette dancing occur in male-female interactions. Kantling is performed in heterosexual contexts but differs because it is usually accompanied by singing (when males display to females, they frequently produce a booming call), and it is significantly shorter. Same-sex displays last for 10-20 minutes, while opposite-sex ones rarely exceed three minutes. Also, symbolic feeding and nest-site displays are {623}

components of heterosexual but not homosexual courtships.

Although no copulation takes place between courting male Ostriches, homosexual mating has been observed in pairs of male Emus. A sexual interaction begins with one male approaching the other, stretching his neck upward and erecting his neck feathers so that they stand out horizontally, while grunting deeply. The two birds begin following and chasing each other; if the male who initiated the activity is behind the other, he may make treading movements with his feet, indicating his intention to mount the other. Often, however, it is the initiating male who lies flat on the ground as an invitation for the other male to mount. The males may also take turns mounting each other. The mounting male lies down behind his partner, resting his breast on the other's rump, and uses his heels to slide forward until he covers most of the other male. While copulation is taking place, the mountee makes soft grunting noises (not usually heard during heterosexual matings), and the mounter gently toys with the feathers on his partner's upper back. After mating, his erect penis is often visible: the male Emu, along with other ratites, is one of the few birds in the world that has a penis (most male birds simply have a cloacal, or genital, opening).

Male Emus also sometimes coparent with each other: two (and occasionally three) males may attend one nest at the same time, incubating all the eggs together. Such nests often contain SUPERNORMAL CLUTCHES of 14-16, and sometimes more than 20, eggs. This is over twice the number found in nests attended by single males, probably because more than one female has laid in them. Unlike single fathers, male coparents are able to take a break from incubating while their partner sits on the nest; they also sometimes roll the eggs between them while on the nest together. Although they are probably not sexually involved with one another, the two fathers cooperate in raising their chicks together, calling to them with "purr-growls" and jointly defending them from predators. A similar phenomenon is found in Greater Rheas: pairs of males occasionally sit on "double nests" that are close to or touching one another; they incubate the eggs together and jointly parent the chicks when they hatch. Most such nests begin as standard nests with only one {624}

male incubating, after which another male joins him and begins transferring eggs to his half of the nest; later, eggs may be transferred back and forth between the twin nests. Unlike Emu nests belonging to male coparents, Rhea double nests usually have a combined number of eggs that is the same as for single nests. Male coparents are different from male nest helpers, which are also found in Rheas. About a quarter of breeding males are assisted by an adolescent male, who incubates and raises (on his own) a clutch of eggs fathered by the adult while the latter goes off to start a new family. This differs from male coparenting in that the two nests are widely separated from one another, each contains the full clutch size of a single nest, the two males never share parenting duties, and the helper is always an adolescent male.

Female Ostriches are occasionally transvestite, having full black-and-white male plumage (along with underdeveloped ovaries).

Joint parenting in male Greater Rheas: two males in Argentina (above) sitting on their double nest, which contains two sets of eggs (below) that are frequently rolled between the coparents

Frequency: Homosexual courtship in Ostriches is quite common in some populations, occurring two to four times a day (usually in the morning). Sexual behavior between male Emus has so far only been observed in captivity, but it does occur repeatedly between partners. Among Greater Rheas, joint parenting between males occurs in about 3 percent of all nests; Emu coparenting probably occurs at a similar rate.

Orientation: In Ostriches, 1-2 percent of all adult males engage in homosexual courtship in some populations. Male Ostriches who court other males typically ignore any females that may be present; they are probably solitary birds that participate in little, if any, heterosexual interactions. Most Emus and Rheas that participate in male coparenting have probably mated and/or paired with females earlier in the season prior to parenting with another male. Male Emus may also have a latent capacity for bisexuality, as evidenced by the occurrence of sexual behavior between captive males (at least one of whom had previously mated heterosexually). However, individual life histories and the full patterns of sexual orientation have not yet been systematically studied in this species.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Heterosexual mating in Ratites occurs in the context of an extraordinary variety of complex social arrangements that deviate significantly from the nuclear-family model. Ostriches have a mating system that has been described as SEMIPROMISCUOUS MONOGAMY. Male and female Ostriches form a type of pair-bond with each other that one biologist describes as a sort of "open marriage," since both partners also copulate with a number of other birds besides their primary partner (birds often mate with a different primary partner each year as well). In addition, females often lay eggs in nests other than their own, especially if they are not the primary partner of a male. As a result, many of the eggs that a pair incubates (and the young they raise) are not necessarily their own. Adoption also occurs when broods are combined to form nursery groups or CRÈCHES — sometimes {625}

containing hundreds of chicks — that are looked after by one or more adults. Emus utilize SERIAL POLYANDRY in their mating system: a male pairs with one female who remains with him until incubation begins, at which point the female leaves her partner and pairs with a new male to begin a second clutch. Many females also seek nonmonogamous matings, copulating with males other than their pair-mate. One study found that the majority of copulations — nearly three-quarters — are promiscuous. In addition, copulation between pair members may be nonprocreative, occurring several months before egg laying. Greater Rheas have a variable mating system that can be characterized as SERIAL POLYGYNANDRY: a male associates with a "harem" of three to ten females, all of whom he mates with. The females lay their eggs communally in one nest; after the male begins to incubate, the females then move on to another male, repeating the process with up to seven different males. As noted above, most Emu and Rhea males are single parents, which can be an arduous task. While tending the eggs, male Rheas rarely leave the nest for more than a few minutes during the six-week incubation period. Male Emus often become severely emaciated and weakened from not eating, drinking, defecating, or leaving the nest during their entire eight-week incubation period. Nonbreeding and failed breeding attempts also occur at high rates among Greater Rheas: less than 20 percent of males even try to reproduce each year, and overall only 5-6 percent of males are successful at breeding each year.

As discussed above, sex-segregated flocks are common among Ostriches, many of whom are not involved in heterosexual pursuits. Also, heterosexual courtship is often not synchronized: females typically begin approaching males several weeks before the latter become sexually interested, and during this time the males often appear to ignore or be indifferent to the females' advances. The onset of the males' sexual cycle is marked by a red flush on the legs and face, as well as enlargement and erection of the penis, which is often displayed in a special "penis-swinging" ceremony. However, once males begin courting, nearly a third of their advances are, in turn, refused by females. Among Emus and Rheas, outright hostility often develops between the sexes once the male starts incubating. Fathers typically threaten, chase, or attack females that try to approach them, while female Emus have been seen responding with vicious double-footed kicks that can tumble males head over heels. Infanticide also sometimes occurs: females that are able to get close to a male tending his chicks may end up killing the youngsters. Egg abandonment or destruction takes place among Ostriches, often of eggs laid by another female. Abandonment also occurs in Greater Rheas, where nearly two-thirds of nests are deserted by males during incubation. In addition, female Rheas who are unable to find a nest and male caretaker for their eggs often lay them in the open and then abandon them; these are known as ORPHAN EGGS. Once (nonorphan) eggs hatch, fathers often adopt youngsters from other broods, raising them alongside their own. Nearly a quarter of male Rheas are adoptive parents, and up to 37 percent of each of their broods may be composed of foster chicks. Researchers have found that adopted young actually have a better chance of surviving than do their stepsiblings.

{626}

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

Bertram, B. C. (1992) The Ostrich Communal Nesting System. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Brown, J. L. (1987) Helping and Communal Breeding in Birds: Ecology and Evolution. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Bruning, D. F. (1974) "Social Structure and Reproductive Behavior in the Greater Rhea." Living Bird 13:251-94.

Coddington, C. L., and A. Cockburn (1995) "The Mating System of Free-Living Emus." Australian Journal of Zoology 43:365-72.

Codenotti, T. L., and F. Alvarez (1998) "Adoption of Unrelated Young by Greater Rheas." Journal of Field Ornithology 69:58-65.

--- (1997) "Cooperative Breeding Between Males in the Greater Rhea Rhea americana." Ibis 139:568-71.

* Curry, P. J. (1979) "The Young Emu and Its Family Life in Captivity." Master's thesis, University of Melbourne.

Fernandez, G. J., and J. C. Reboreda (1998) "Effects of Clutch Size and Timing of Breeding on Reproductive Success of Greater Rheas." Auk 115:340-48.

* --- (1995) "Adjacent Nesting and Egg Stealing Between Males of the Greater Rhea Rhea americana." Journal of Avian Biology 26:321-24.

Fleay, D. (1936) "Nesting of the Emu." Emu 35:202-10.

Folch, A. (1992) "Order Struthioniformes." In J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, and J. Sargatal, eds., Handbook of the Birds of the World, vol. 1: Ostrich to Ducks, pp. 76-110. Barcelona: Lynx Edici6ns.

* Gaukrodger, D. W. (1925) "The Emu at Home." Emu 25:53-57.

* Heinroth, O. (1927) "Berichtigung zu 'Die Begattung des Emus (Dromaeus novae-hollandiae)' [Correction to 'Mating Behavior of Emus']." Ornithologische Monatsberichte 35:117-18.

* --- (1924) "Die Begattung des Emus, Dromaeus novae-hollandiae [Mating Behavior of Emus]." Ornithologische Monatsberichte 32:29-30.

* Hiramatsu, H., K. Tasaka, S. Shichiri, and F. Hashizaki (1991) "A Case of Masculinization in a Female Ostrich." Journal of Japanese Association of Zoological Gardens and Aquariums 33:81-84.

Navarro, J. L., M. B. Martella, and M. B. Cabrera (1998) "Fertility of Greater Rhea Orphan Eggs: Conservation and Management Implications." Journal of Field Ornithology 69:117-20.

O'Brien, R. M. (1990) "Emu, Dromaius novaehollandiae." In S. Marchant and P. J. Higgins, eds., Handbook of Australian, New Zealand, and Antarctic Birds, vol. 1, part A, pp. 47-58. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Raikow, R. J. (1968) "Sexual and Agonistic Behavior of the Common Rhea." Wilson Bulletin 81:196-206.

* Sauer, E. G. F. (1972) "Aberrant Sexual Behavior in the South African Ostrich." Auk 89:717-37.

Sauer, E. G. F., and E. M. Sauer (1966) "The Behavior and Ecology of the South African Ostrich." Living Bird 5:45-75.

{627}

Penguins

Penguins

HUMBOLDT PENGUIN (Spheniscus humboldti)

IDENTIFICATION: A small penguin (approximately 2 feet tall) with a black band on its chest and patches of red skin at the base of its bill. DISTRIBUTION: Coastal Peru to central Chile. HABITAT: Marine areas; nests on islands or rocky coasts. STUDY AREAS: Emmen Zoo, the Netherlands; Washington Park Zoo, Portland, Oregon.

KING PENGUIN (Aptenodytes patagonicus)

IDENTIFICATION: A large (3 foot tall) penguin with orange ear patches and a yellow-orange wash on the breast. DISTRIBUTION: Sub-Antarctic seas. HABITAT: Oceans; nests on islands and beaches. STUDY AREA: Edinburgh Zoo, Scotland; subspecies A.p. patagonicus.

GENTOO PENGUIN (Pygoscelis papua)

IDENTIFICATION: A medium-sized penguin (up to 2 1/2 feet) with a white patch above the eye. DISTRIBUTION: Circumpolar in Southern Hemisphere. HABITAT: Oceans; nests on islands and coasts. STUDY AREAS: South Georgia, Falkland Islands; Edinburgh Zoo, Scotland; subspecies

P.p. papua.

Social Organization

Humboldt Penguins form mated pairs during the breeding season and nest in small colonies; they travel and feed at sea in social groups of 10-60 birds. King Penguins are highly gregarious, breeding in enormous colonies — some numbering 300,000 pairs — and generally form monogamous pair-bonds. Gentoo Penguins have a similar social system, although their nesting colonies are not as large.

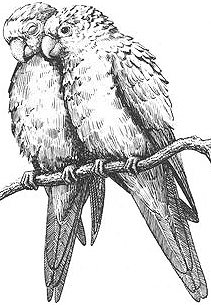

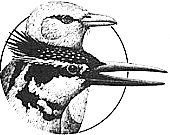

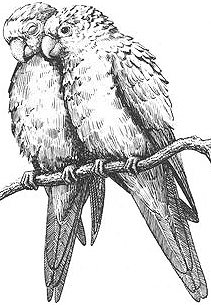

A female King Penguin urging another female to lie down prior to mounting her

Description

Behavioral Expression: Lifelong homosexual pair-bonds sometimes develop between male Humboldt Penguins. Like heterosexual pairs, same-sex partners remain together for many years: some male couples have stayed together for up to six years, until the death of one of the partners. Same-sex pairs (like opposite-sex pairs) spend much of their time close together, often touching. They also usually live together in a nest that they have built — either an underground burrow, a {628}

shallow bowl dug in the ground, or a rock niche lined with twigs. Unlike male pairs in other birds, though, homosexual pairs of Humboldt Penguins never acquire any eggs. Courtship and pair-bonding activities are also a prominent aspect of homosexual partnerships. This includes the ECSTATIC DISPLAY, in which a male stretches his head and neck upward, spreading his flippers wide and flapping them while emitting several long, very loud donkeylike brays. Sometimes this is performed mutually by both males standing side by side. Homosexual partners also ALLO-PREEN each other, affectionately running their bills through one another's feathers. Occasional same-sex BOWING also occurs, in which one male points his beak down toward his partner and vibrates his head from side to side. As a prelude to copulation, one male approaches the other from behind, pressing against his body and vibrating his flippers against his partner; this distinctive display is known as the ARMS ACT. Homosexual copulation occurs when the bird in front lies down on his chest, allowing the other male to climb onto his back; genital contact may occur when the male being mounted holds his tail up or to the side and exposes his cloaca. Homosexual mountings are sometimes briefer than heterosexual ones, but often the two males take turns mounting each other. Not all same-sex courtship and sexual activity occurs between birds in homosexual pairs. Males who are paired to females also sometimes court and copulate with other heterosexually paired males (as well as with females other than their own mate).

In King Penguins, same-sex pairs also occur, in both males and females. These bonds are probably not as long-lasting as homosexual pairs in Humboldts, since same-sex partners sometimes divorce each other after being together for only one season (which also occurs commonly in heterosexual pairs in this species). Courtship activities are a part of King Penguin homosexual pair-bonds, especially between males. One such display is BOWING, in which one bird approaches the other while making courtly bows, often leading to mutual bowing. Another display is DABBLING, in which the birds face each other while rapidly clapping their bills and gently nibbling or preening one another's feathers, sometimes accompanied by quivering of the flippers and tail. This may lead to homosexual copulation, in which one bird urges the other to lie down by pressing on its back, then mounts; this occurs among both males and females. In addition, female pairs sometimes lay an (infertile) egg, which they take turns incubating.

Homosexual courtship also occurs early in the breeding season among Gentoo Penguins. A male or a female brings an "offering" of pebbles or grass and lays it at the feet of another bird of the same sex, {629}

bowing and making slight hissing noises. The other bird, if interested, may respond with bowing or arranging the material into a nest. Females that pair with each other usually lay eggs in the nest that they tend together; because these birds do not typically mate with males, their eggs are infertile. However, female pairs can become successful foster parents in captivity, incubating and hatching fertile eggs when provided and successfully raising the resulting chicks.

Frequency: In some zoo populations of Humboldt Penguins, at least 5 percent of all pairs are homosexual, and 12 percent of all copulations are between males. Among paired birds, 10 percent of mountings take place in male couples, while 15 percent of promiscuous matings (between nonmates) are homosexual. Of courtship displays performed by males to birds other than their partner, about a quarter of all arms acts are homosexual, and about 2 percent of courtship bows are same-sex. In one zoo colony consisting of five King Penguins, 2 out of 10 bonds that formed among the birds over a period of nine years were homosexual. Although same-sex matings have not yet been observed in these species in the wild, homosexual courtship has been seen in wild Gentoo Penguins: in one informal survey, 3 out of 13 courtships (23 percent) by Gentoos were same-sex.

Orientation: Some male Humboldt Penguins are exclusively homosexual, remaining with their male partners for their entire lives, or else re-pairing with another male should they lose their original partner. Other males are sequentially bisexual, pairing with a male after having lost one or more previous female mates. Still other males are simultaneously bisexual, engaging in both same-sex and opposite-sex courtship and copulation. Of these, some have a primary heterosexual bond but occasionally engage in homosexual activity with another breeding male: about 47 percent of all same-sex copulations are of this type (as opposed to occurring between bonded partners). In a few cases, the opposite occurs: a male with a primary homosexual pair-bond occasionally participates in a heterosexual copulation. Among King Penguins, birds in same-sex pairs are probably exclusively homosexual for the duration of their pair-bonds (since any eggs that are laid are infertile), and birds exhibit a "preference" for same-sex mates even when unpaired birds of the opposite sex are available. Over the course of their lives, however, most such birds are sequentially bisexual, since following the breakup of a homosexual pair they may go on to form heterosexual pair-bonds and even raise a family. Most Gentoo Penguins that participate in homosexual courtship are probably bisexual, since they court both males and females, albeit with a primary heterosexual orientation (since most go on to breed with birds of the opposite sex). Females that pair with each other are exclusively homosexual for the duration of their bond (which may last for one or both birds' lives); some females pair with a heterosexual mate after the death of their female partner.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

As noted above, promiscuous matings by heterosexually paired birds are common in Humboldt Penguins: one-third to one-half of all heterosexual copulations {630}

are between nonpair members, and courtship of birds other than one's mate is also frequent. Promiscuous courtship and copulation occur in King and Gentoo Penguins as well. Even within pairs, sexual behavior may be nonprocreative. In Humboldts, copulation occurs both early and late in the breeding season, when the chances of fertilization are low or nonexistent, while heterosexual mounts (like homosexual ones) sometimes do not include genital contact or sperm transfer (in both Humboldts and Gentoos). Female Gentoo Penguins sometimes mount their mates (REVERSE mounting), while male Gentoos occasionally masturbate by mounting and copulating with clumps of grass. Males have also been observed trying to copulate with dead Penguins.

Several other variations on the lifetime monogamous pair-bond and nuclear family also occur. About a quarter of all Humboldt male-female pairs divorce, often when the female leaves her mate for another male. Divorce also occurs in 10-50 percent of Gentoo pairs, and in some years no pairs remain together. It is especially common in King Penguins, where only about 30 percent of birds retain the same mate from one season to the next. In addition, some King Penguins abandon their mates during the breeding season, and about 6 percent of chicks are reared by single parents (either abandoned or widowed). Humboldts occasionally form trios consisting of either one male and two females or two females and one male; these make up about 5 percent of all heterosexual bonds. In King Penguins, nonbreeding females may associate with a heterosexual pair and help them raise their chick, who recognizes all three birds as its parents; single parenting is also common. Nonbreeders that aren't part of trios also occasionally feed chicks belonging to other birds, particularly when the chicks are in CRÈCHES. These large nursery groups, sometimes containing thousands of chicks, form while the parents are away. Creches also occur in Gentoos, where they are often attended by several adult "guardians." During the winter, King parents are often gone for long periods on fishing trips, and chicks may not be fed for weeks or months at a time. As many as 10 percent of them perish from this prolonged fasting and starvation. Some parents abandon their chicks or eggs (especially in severe weather), and chicks may also be killed in squabbles between their parents and nonbreeding birds that are trying to "kidnap" them. King Penguins also occasionally "steal" other pairs' eggs.

Breeding can take its toll on adults as well: male King Penguins fast for more than fifty days during courtship and incubation, losing 10-12 percent of their body weight. In addition, heterosexual copulations are sometimes harassed, with throngs of neighboring birds converging on mating pairs, attacking them and trying to interrupt the sexual activity. Many birds forgo breeding altogether: more than 40 percent of the population each year consists of nonbreeders, and birds generally do not breed every year (primarily because of the unusually long 16 — month breeding cycle). Extensive nonbreeding is also a feature of Gentoo populations: up to a quarter of the adults may skip breeding each year, and more than 15 percent of birds breeding late in the season lay infertile clutches. In addition, breeding is delayed for one to two years in younger King and Gentoo Penguins, due to both physiological and social factors. Some Humboldt Penguins remain single and nonbreeding as well, although they may still engage in sexual behavior with other birds.

{631}

Other Species

Reciprocal homosexual copulations — involving full genital (cloacal) contact — also occur among male Adelie Penguins (Pygoscelis adeliae) in Antarctica, accompanied by courtship displays such as DEEP BOWING and the ARMS ACT. Following ejaculation by the mounter, the mountee contracts his cloaca, perhaps facilitating movement of his partner's semen in his genital tract and/or indicating orgasm. Some males who participate in homosexual activity also mate heterosexually.

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

Bagshawe, T. W. (1938) "Notes on the Habits of the Gentoo and Ringed or Antarctic Penguins." Transactions of the Zoological Society of London 24:185-306.

Bost, C. A., and P. Jouventin (1991) "The Breeding Performance of the Gentoo Penguin Pygoscelis papua at the Northern Edge of Its Range." Ibis 133:14-25.

* Davis, L. S., F. M. Hunter, R. G. Harcourt, and S. M. Heath (1998) "Reciprocal Homosexual Mounting in Adelie Penguins Pygoscelis adeliae." Emu 98:136-37.

* Gillespie, T. H. (1932) A Book of King Penguins. London: Herbert Jenkins Ltd.

Kojima, I. (1978) "Breeding Humboldt's Penguins Spheniscus humboldti at Kyoto Zoo." International Zoo Yearbook 18:53-59.

* Merritt, K., and N. E. King (1987) "Behavioral Sex Differences and Activity Patterns of Captive Humboldt Penguins." Zoo Biology 6:129-38.

* Murphy, R. C. (1936) Oceanic Birds of South America, vol. 1, p.340. New York: American Museum of Natural History.

Olsson, O. (1996) "Seasonal Effects of Timing and Reproduction in the King Penguin: A Unique Breeding Cycle." Journal of Avian Biology 27:7-14.

* Roberts, B. (1934) "The Breeding Behavior of Penguins, with Special Reference to Pygoscelis papua (Forster)." British Graham Land Expedition Science Report 1:195-254.

Schmidt, C. R. (1978) "Humboldt's Penguins Spheniscus humboldti at Zurich Zoo." International Zoo Yearbook 18:47-52.

* Scholten, C. J. (1996) Personal communication.

* --- (1992) "Choice of Nest-site and Mate in Humboldt Penguins (Spheniscus humboldti)" SPN (Spheniscus Penguin Newsletter) 5:3-13.

* --- (1987) "Breeding Biology of the Humboldt Penguin Spheniscus humboldti at Emmen Zoo." International Zoo Yearbook 26:198-204.

* Stevenson, M. F. (1983) "Penguins in Captivity." Avicultural Magazine 89:189-203 (reprinted in International Zoo News 189 [1985]:17-28).

Stonehouse, B. (1960) "The King Penguin Aptenodytes patagonica of South Georgia. 1. Breeding Behavior and Development." Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey Scientific Reports 23:1-81.

van Zinderen Bakker, E. M., Jr. (1971) "A Behavior Analysis of the Gentoo Penguin Pygoscelis papua." In E. M. van Zinderen Bakker Sr., J. M. Winterbottom, and R. A. Dyer, eds., Marion and Prince Edward Islands: Report on the South African Biological and Geological Expedition, pp. 251-72. Cape Town: A. A. Balkema.

Weimerskirch, H., J. C. Stahl, and P. Jouventin (1992) "The Breeding Biology and Population Dynamics of King Penguins Aptenodytes patagonica on the Crozet Islands." Ibis 134:107-17.

* Wheater, R. J. (1976) "The Breeding of Gentoo Penguins Pygoscelis papua in Edinburgh Zoo." International Zoo Yearbook 16:89-91.

Williams, T. D. (1996) "Mate Fidelity in Penguins." In J. M. Black, ed., Partnerships in Birds: The Study of Monogamy, pp. 268-85. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

--- (1995) The Penguins: Spheniscidae. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Williams, T. D., and S. Rodwell (1992) "Annual Variation in Return Rate, Mate and Nest-Site Fidelity in Breeding Gentoo and Macaroni Penguins." Condor 94:636-45.

Wilson, R. P., and M.-P. T. Wilson (1990) "Foraging Ecology of Breeding Spheniscus Penguins." In L. S. Davis and J. T. Darby, eds., Penguin Biology, pp. 181-206. San Diego: Academic Press.

{632}

BIRDS OF PREY AND GAME BIRDS

Raptors

Raptors

(Common) KESTREL (Falco tinnunculus)

IDENTIFICATION: A small falcon (12-15 inches) having chestnut plumage spotted with black, and a gray head and tail in males. DISTRIBUTION: Throughout Eurasia and Africa. HABITAT: Variable, including plains, steppe, woodland, wetlands. STUDY AREA: Niva, Denmark; subspecies F.t. tinnunculus.

(Eurasian) GRIFFON VULTURE (Gyps fulvus)

IDENTIFICATION: A large vulture (wingspan up to 9 feet) with a white head and neck and brown plumage. DISTRIBUTION: Southern Europe, North Africa, Middle East to Himalayas. HABITAT: Mountains, steppe, forest. STUDY AREAS: Berlin Zoo; Jonte Gorge and other regions of the Massif Central Mountains, France; Lumbier, Spain; subspecies

G.f. fulvus.

Social Organization

During early spring through summer, Kestrels associate as mated pairs that each have their own territory; there is also a significant subpopulation of nonbreeding birds. Outside of the mating season, males and females are often segregated from each other and largely solitary: sometimes only one member of a pair — typically the female — migrates, though males that migrate often travel farther than females. During the winter, males and females also tend to occupy separate habitats, with males generally in more wooded areas. Griffon Vultures are much more social and tend to nest in colonies containing 15-20 pairs, sometimes as many as 50-100. As in Kestrels, mated pairs often last for many years.

{633}

Description

Behavioral Expression: In Kestrels and Griffon Vultures, two birds of the same sex — usually males — occasionally bond with each other and become a mated pair. Male Kestrels in a homosexual pair often soar together in the early spring, performing dramatic courtship display flights that reinforce their pair-bond (these displays are also found in heterosexual pairs). One such display is the ROCKING FLIGHT, in which the two partners fly at an immense height and rock from side to side, using flicking wingbeats. Another display is the slower WINNOWING FLIGHT, in which the wings beat with shallow, almost vibrating strokes, giving the impression that only the tips are moving or "shivering." Both displays are accompanied by distinctive calls, such as the TSIK CALL — a series of clipped notes sounding like tsick or kit — and the LAHN CALL, a sequence of high-pitched trills transcribed as quirrr-rr quirrr-rr. The two males sometimes display together, or one male might soar while the other sits on his perch. Same-sex partners also copulate with each other, making the distinctive copulation call sounding like kee-kee-kee or kik-kik-kik; homosexual mounts last for 10-15 seconds (comparable to heterosexual matings).

Male Griffon Vultures in homosexual pairs also mate with each other repeatedly beginning in December (the onset of the mating season), and such pairs may remain together for years. The two males sometimes build a nest together each year — typically a flat assemblage of sticks on a crag, two to three feet across. Like Kestrels, pairs of Griffon Vultures perform a spectacular aerial pair-bonding display called TANDEM FLYING. The two birds spiral upward to a great height on a thermal, then glide downward in a path that will bring them extremely close to each other, "riding" for a few seconds one above the other, until they separate again. Although most tandem flights are by heterosexually paired birds, Vultures of the same sex also engage in this activity.

Frequency: Homosexual pairs probably occur only occasionally in Kestrels, although no systematic study of their frequency has been undertaken. Male pairs of Griffon Vultures have not yet been fully verified in the wild; however, tandem flights between same-sex partners (both males and females) account for about 20 percent of all display flights in the wild, and some of these probably represent homosexual pairings.

Orientation: No detailed studies of the life histories of birds of prey in homosexual pairs have yet been conducted. However, at least some male Griffon Vultures in same-sex tandem flights have female mates, suggesting a possible form of bisexuality, while at least some younger females in same-sex tandems likely have no prior heterosexual experience.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

In any given year, many Kestrels do not breed: about a third of all birds in some populations are unpaired, while 6-13 percent of heterosexually mated birds do not {634}

lay eggs. Male-female pairs of Griffon Vultures, too, may abstain from procreating — some pairs go for as long as eight or nine consecutive years without reproducing. Nonlaying pairs, as well as younger Griffon Vultures that have not yet begun breeding, nevertheless still engage in sexual activity, often mating with each other near the breeding colonies. Several other types of nonprocreative copulations are also prominent in these species. Both Kestrels and Griffon Vultures sometimes mate outside of the breeding season (in the autumn and winter) and during the breeding season when there is no chance of fertilization. This includes during incubation, chick-raising, or very early in the season. Outside of the breeding season, though, Griffon females may refuse to participate in copulations, attacking their male partner when he tries to mount. Kestrel males and females very often live separately during the winter (as discussed above). In addition, heterosexual mating in both species occurs at astonishingly high rates, indicating that it is not simply procreative activity: Griffon heterosexual pairs sometimes mate every half hour, while Kestrels average a copulation once every 45 minutes, or seven to eight times per day during the breeding season. Even higher rates have been recorded for some Kestrels — up to three times per hour — and it is estimated that each Kestrel pair mates as many as 230 times during the breeding season alone. Male Kestrels also sometimes court and attempt to mate with females other than their mate; they usually do not succeed, though, owing to resistance by the female and defense by her mate. Nevertheless, 5-7 percent of all broods contain chicks fathered by a bird other than its mother's mate, and in a few cases none of the nestlings are genetically related to their caretaking father. Nonmonogamous copulations probably also occur in Griffon Vultures.

Alternative heterosexual family arrangements are widespread in Kestrels: up to 10 percent of males in some years have two female mates (they usually each have families in separate nests), while a female sometimes forms a trio with two males. Divorce is fairly common in Kestrels: about 17 percent of females and 6 percent of males change partners between breeding seasons, and sometimes a pair splits during the breeding season as well. In Griffon Vultures the divorce rate is about 5 percent. Some Kestrel males are unable to provide their mates with enough food during incubation, resulting in desertion and loss of the entire clutch (accounting for more than half of all nesting failures). Finally, cannibalism has been documented in these species: Kestrel nestlings sometimes kill and eat their siblings, while parents of both species cannibalize their own chicks on rare occasions (usually if the chick has already died).

Other Species

Same-sex pairing and coparenting have been observed in other birds of prey in captivity. Female Barn Owls (Tyto alba) that are raised together occasionally bond with one another, ignoring any available males. They may even nest together, each laying a clutch of infertile eggs that they incubate side by side. Female coparents share parenting duties and can successfully raise foster young. Courtship, pair-bonding, nesting, and coparenting of foster chicks have also been documented in a pair of female Powerful Owls (Ninox strenua) from Australia. In addition, a pair of {635}

male Steller's Sea Eagles (Haliaeetus pelagicus) — a species native to Siberia and East Asia — courted one another and built a nest together. They even incubated and hatched another eagle's egg and successfully raised the chick together.

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

Blanco, G., and F. Martinez (1996) "Sex Difference in Breeding Age of Griffon Vultures (Gyps fulvus)." Auk 113:247-48.

Bonin, B., and L. Strenna (1986) "The Biology of the Kestrel Falco tinnunculus in Auxois, France." Alauda 54:241-62.

Brown, L., and D. Amadon (1968) "Gyps fulvus, Griffon Vulture." In Eagles, Hawks, and Falcons of the World, pp. 325-28. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Cramp, S., and K. E. L. Simmons, eds. (1980) "Griffon Vulture (Gyps fulvus)" and "Kestrel (Falco tinnunculus )." In Handbook of the Birds of Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa, vol. 2, pp. 73-81, 289-300. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

* Fleay, D. (1968) Nightwatchmen of Bush and Plain: Australian Owls and Owl-like Birds. Brisbane: Jacaranda Press.

* Heinroth, O., and M. Heinroth (1926) "Der Gansegeier (Gyps fulvus Habl.) [The Griffon Vulture]." In Die Vogel Mitteleuropas, vol. 2, pp. 66-69. Berlin and Lichterfeld: Bermuhler.

* Jones, C. G. (1981) "Abnormal and Maladaptive Behavior in Captive Raptors." In J. E. Cooper and A. G. Greenwood, eds., Recent Advances in the Study of Raptor Diseases (Proceedings of the International Symposium on Diseases of Birds of Prey, London, 1980), pp. 53-59. West Yorkshire: Chiron Publications.

Korpimaki, E. (1988) "Factors Promoting Polygyny in European Birds of Prey — A Hypothesis." Oecologia 77:278-85.

Korpimaki, E., K. Lahti, C. A. May, D. T. Parkin, G. B. Powell, P. Tolonen, and J. H. Wetton (1996) "Copulatory Behavior and Paternity Determined by DNA Fingerprinting in Kestrels: Effects of Cyclic Food Abundance." Animal Behavior 51:945-55.

Mendelssohn, H., and Y. Leshem (1983) "Observations on Reproduction and Growth of Old World Vultures." In S.R. Wilbur and J. A. Jackson, eds., Vulture Biology and Management, pp. 214-41. Berkeley: University of California Press.

* Mouze, M., and C. Bagnolini (1995) "Le vol en tandem chez le vautour fauve (Gyps fulvus) [Tandem Flying in the Griffon Vulture]." Canadian Journal of Zoology 73:2144-53.

* Olsen, K. M. (1985) "Pair of Apparently Adult Male Kestrels." British Birds 78:452-53.

Packham, C. (1985) "Bigamy by the Kestrel." British Birds 78:194.

* Pringle, A. (1987) "Birds of Prey at Tierpark Berlin, DDR." Avicultural Magazine 93:102-6.

Sarrazin, F., C. Bagnolini, J. L. Pinna, and E. Danchin (1996) "Breeding Biology During Establishment of a Reintroduced Griffon Vulture Gyps fulvus Population." Ibis 138:315-25.

Stanback, M. T., and W. D. Koenig (1992) "Cannibalism in Birds." In M. A. Elgar and B. J. Crespi, eds., Cannibalism: Ecology and Evolution Among Diverse Taxa, pp. 277-98. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Terrasse, J. F., M. Terrasse, and Y. Boudoint (1960) "Observations sur la reproduction du vautour fauve, du percnoptere, et du gypaete barbu dans les Basses-Pyrenees [Observations on the Reproduction of the Griffon Vulture, the Egyptian Vulture, and the Bearded Vulture in the Lower Pyrenees]." Alauda 28:241-57.

Village, A. (1990) The Kestrel. London: T. and A. D. Poyser.

{636}

Grouse

Grouse

SAGE GROUSE (Centrocercus urophasianus)

IDENTIFICATION: A gray-brown grouse with speckled plumage, pointed tail feathers, and inflatable air sacs in the breast. DISTRIBUTION: Western North America. HABITAT: Sage grassland, semidesert. STUDY AREAS: Green River Basin and Laramie Plains, Wyoming; Long Valley, California.

RUFFED GROUSE (Bonasa umbellus)

IDENTIFICATION: A large grouse with a banded, fan-shaped tail and distinctive black ruffs on the side of the neck. DISTRIBUTION: Northern and central North America. HABITAT: Forest. STUDY AREA: In captivity in Ithaca, New York.

Social Organization

During the breeding season, male Ruffed and Sage Grouse display on territories — large, communal "strutting grounds" or LEKS in Sage Grouse, and individual "drumming logs" in Ruffed Grouse. Both species have a promiscuous mating system, in which birds mate with multiple partners, do not form pair-bonds, and females care for the young with no male assistance. Outside of the mating season, birds sometimes congregate in mixed-sex flocks.

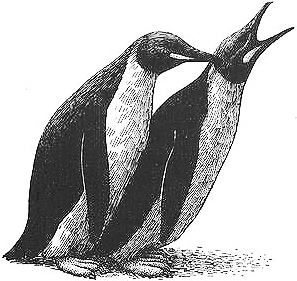

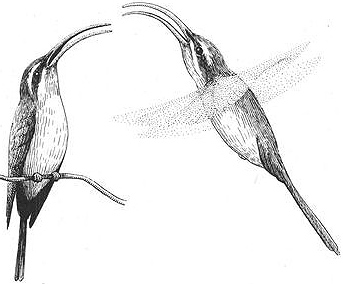

Homosexual courtship in Sage Grouse: a female performing the "strutting" display on the plains of Wyoming

Description

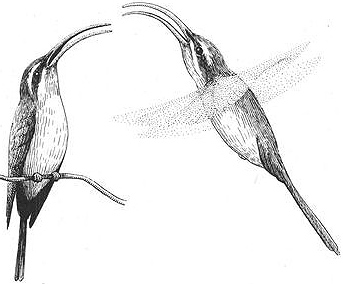

Behavioral Expression: At dawn on their prairie display grounds, female Sage Grouse gather in groups of eight to ten (or sometimes more) known as CLUSTERS. Although many are there to mate with males, some females also court and mate with each other. Homosexual courtship display is similar to that used by males and is called STRUTTING. The female takes short steps forward and turns while presenting herself in a spectacular posture — long tail feathers fanned in a circle, air sacs in the breast expanded, and neck feathers erected and rustling. Unlike males, however, strutting females do not make the characteristic "plopping" sound during courtship, owing to the smaller size of their air sacs. When the female has finished her strut, another female may solicit a copulation from her by crouching down, arching her wings and fanning the wing feathers on the ground. The other female {637}

mounts her and often performs a complete mating sequence, spreading her wings on either side of the mounted female for balance, treading on her back with her feet, and lowering and rotating the tail for cloacal (genital) contact. Some females also chase others in the group and try to mount them, and "pile-ups" of three or four females all mounted on each other sometimes develop. During most lesbian matings, males pay no attention to the females. Sometimes, however, they try to disrupt a lesbian mounting, or they may even try to join in by mounting a female who is herself mounted on another female. In one case, a male even mounted another male who was himself mounted on two females that were mounting each other! Later in the breeding season, two females also sometimes jointly parent their offspring, combining all their chicks into a single brood that they both look after.

Male Ruffed Grouse also court and mount each other. Deep in the forest, each male advertises his presence by DRUMMING at dawn or dusk, producing a throbbing, drumroll-like sound by rapidly "beating" the air with his wings. If another Grouse lands on the drumming log, he begins his strutting display. Fanning his tail like a turkey, he lowers his wings, erects his neck ruffs, and rotates his head vigorously, all the while emitting a hissing sound as he approaches the other bird. If the other bird is a female, mating takes place, whereas if it is another male, typically a fight will ensue. However, in some cases the other male does not challenge the displaying male. The courting male then makes a "gentle" approach, sleeking down his feathers, dragging his tail on the ground, and occasionally shaking his head. He sometimes pecks softly at the base of the other male's bill or places his foot on the other's back and may mount him as in heterosexual copulation (although the mounted bird does not usually adopt the female's typical copulatory posture).

Homosexual group copulation in Sage Grouse: a female crouching with outstretched wings (left) is being mounted by another female (center, upright bird), who is simultaneously being mounted by a third female (right, with its neck extended over the back of the second female). A fourth female (foreground, facing front), is not part of this "pile-up."

{638}

Frequency: Approximately 2-3 percent of Sage Grouse females participate in homosexual courtships and copulations, which occur in perhaps one out of five female visits to the lek (on average); the prevalence of homosexual behavior in wild Ruffed Grouse is not known.

Orientation: Some female Sage Grouse that mate with females do not apparently engage in heterosexual copulation; others alternate between homosexual and heterosexual activity (sometimes within a few hours or minutes). As described above, bisexual "pile-ups" involving birds of the same and opposite sexes mounting each other simultaneously also occur. In Ruffed Grouse, little is known about homosexual activity in the wild, but it is likely that there is a similar combination of bisexuality with occasional exclusive homosexuality. Displaying males that mount other males probably also court and mate with females, while those males who approach displaying males are most likely nondrumming "alternate" males (see below) that do not mate heterosexually.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

In both of these species, significant portions of the population are nonbreeding. As many as 30 percent of male Ruffed Grouse are nondrummers who do not mate heterosexually, and some birds never breed during their entire lives. In fact, one researcher found that nonbreeders live longer and have a better survival rate than breeders. Many nonbreeders are younger males who have yet to acquire a drumming log; others are ALTERNATE males that tend to associate with another male on his display site without themselves drumming. Still others give up or "abdicate" their display territories and become nonbreeders. Up to 25 percent of female Ruffed Grouse may not nest in any given year, as is true for 20-32 percent of female Sage Grouse in some populations. Moreover, 14-16 percent of female Sage Grouse abandon their nests (especially if they have been disturbed), which means that any eggs or chicks they have will not survive; this also occasionally occurs in Ruffed Grouse. The majority of Sage Grouse copulations are performed by only a small fraction of the male population, and one-half to two-thirds of males never mate at all; during each breeding season, 3-6 percent of females do not ovulate either.

Even among birds that do mate, heterosexual copulation is often complicated by a host of factors: female Sage Grouse may refuse to be mounted, males often ignore females' solicitations to mate (especially later in the breeding season), and 10-18 percent of copulations are disrupted by neighboring males who attack mating birds. In addition, males and females are often physically separated from each other: in both species, typically the only contact the two sexes have with each other during the breeding season is mating. Since each female usually copulates only once, hers is a largely male-free existence. Even on the display grounds, Sage Grouse are typically sex-segregated when not actually mating. Several types of alternative sexual behavior also occur in these species. Male Sage Grouse often "masturbate" by mounting a pile of dirt or a dunghill and performing all the motions of a full copulation. Both male Ruffed and Sage Grouse occasionally court and mate with {639}

females of other grouse species. And male Sage Grouse sometimes mount females without attempting to inseminate them (no genital contact). Moreover, even though most females mate only once (that is, the minimum required to fertilize their eggs), multiple copulations also occasionally occur: one female, for example, was mounted more than 22 times in one hour. Female Sage Grouse sometimes combine their youngsters into what is known as a GANG BROOD, a communal "nursery flock" of sorts.

Other Species

Homosexual activity occurs in several species of pigeons. Feral Rock Doves (Columba livia), for example, form both male and female same-sex pairs that engage in a full suite of courtship, pair-bonding, sexual, and nesting activities. Homosexual pairs of female Ring Doves (Streptopelia risoria) in captivity are generally more devoted incubators than heterosexual pairs, being less likely to abandon their eggs.

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

* Allen, A. A. (1934) "Sex Rhythm in the Ruffed Grouse (Bonasa umbellus Linn.) and Other Birds." Auk 51:180-99.

* Allen, T. O., and C. J. Erickson (1982) "Social Aspects of the Termination of Incubation Behavior in the Ring Dove (Streptopelia risoria)." Animal Behavior 30:345-51.

Bergerud, A. T., and M. W. Gratson (1988) "Survival and Breeding Strategies of Grouse." In A. T. Bergerud and M. W. Gratson, eds., Adaptive Strategies and Population Ecology of Northern Grouse, pp. 473-577. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

* Brackbill, H. (1941) "Possible Homosexual Mating of the Rock Dove." Auk 58:581.

* Gibson, R. M., and J. W. Bradbury (1986) "Male and Female Mating Strategies on Sage Grouse Leks." In D. 1. Rubenstein and R. W. Wrangham, eds., Ecological Aspects of Social Evolution, pp. 379-98. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Gullion, G. W. (1981) "Non-Drumming Males in a Ruffed Grouse Population." Wilson Bulletin 93:372-82.

--- (1967) "Selection and Use of Drumming Sites by Male Ruffed Grouse." Auk 84:87-112.

Hartzler, J. E. (1972) "An Analysis of Sage Grouse Lek Behavior." Ph.D. thesis, University of Montana.

Hartzler, J. E., and D. A. Jenni (1988) "Mate Choice by Female Sage Grouse." In A. T. Bergerud and M. W. Gratson, eds., Adaptive Strategies and Population Ecology of Northern Grouse, pp. 240-69. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Johnsgard, P. A. (1989) "Courtship and Mating." In S. Atwater and J. Schnell, eds., Ruffed Grouse, pp. 112-17. Harrisburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books.

* Johnston, R. F., and M. Janiga (1995) Feral Pigeons. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lumsden, H. G. (1968) "The Displays of the Sage Grouse." Ontario Department of Lands and Forests Research Report (Wildlife) 83:1-94.

* Patterson, R. L. (1952) The Sage Grouse in Wyoming. Denver: Sage Books.

Schroeder, M. A. (1997) "Unusually High Reproductive Effort by Sage Grouse in a Fragmented Habitat in North-Central Washington." Condor 99:933-41.

* Scott, J. W. (1942) "Mating Behavior of the Sage Grouse." Auk 59:477-98.

Simon, J. R. (1940) "Mating Performance of the Sage Grouse." Auk 57:467-71.

Wallestad, R. (1975) Life History and Habitat Requirements of Sage Grouse in Central Montana. Helena: Montana Department of Fish and Game.

* Wiley, R. H. (1973) "Territoriality and Non-Random Mating in Sage Grouse, Centrocercus urophasianus." Animal Behavior Monographs 6:87-169.

{640}

HUMMINGBIRDS, WOODPECKERS, AND OTHERS

Hummingbirds

Hummingbirds

LONG-TAILED HERMIT HUMMINGBIRD (Phaethornis superciliosus)

IDENTIFICATION: A medium-sized hummingbird with purplish or greenish bronze upperparts, a striped face, a long, downward-curving bill, and elongated tail feathers. DISTRIBUTION: Southwestern Mexico, Central America, northwestern South America. HABITAT: Tropical forest undergrowth. STUDY AREA: La Selva Biological Reserve, Sarapiqui, Costa Rica.

ANNA'S HUMMINGBIRD (Calypte anna)

IDENTIFICATION: A medium-sized hummingbird (up to 4 inches long) with an iridescent, rose-colored throat and crown (in males), and a bronze-green back. DISTRIBUTION: Western United States to northwestern Mexico. HABITAT: Woodland, chaparral, scrub, meadows. STUDY AREA: Franklin Canyon, Santa Monica Mountains, California.

Social Organization

Long-tailed Hermit Hummingbirds form singing assemblies or LEKS composed of about a dozen males and have a polygamous or promiscuous mating system (in which birds mate with multiple partners). Anna's Hummingbirds are not particularly social: each bird defends its own territory and does not generally associate with others. No pair formation occurs as part of the mating system; instead, males and probably also females mate with several different partners.

{641}

Description

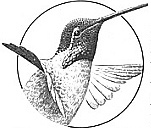

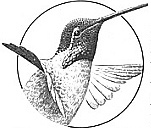

Behavioral Expression: Male Long-tailed Hermit Hummingbirds gather on their leks or courtship display territories in dense, stream-side thickets, singing to advertise their presence and attract birds to mate with. Their monotonous songs consist of single notes of various types — sometimes transliterated as kaching, churk, shree, or chrrik — repeated for up to 30 minutes at a time. Females and males visit the leks, and both sexes may be courted and mounted by the territorial males. In a typical homosexual encounter, a male approaches another male that has landed on his territory and performs an aerial maneuver known as the FLOAT. In this display, he slowly flies back and forth in front of the perched male, pivoting his body from side to side. Often he holds his bill wide open, exposing his bright orange mouth lining and striking facial stripes, which combine to produce an arresting visual pattern. The perched bird may respond by gaping his own bill and "tracking" the movements of the swiveling and hovering male in front of him, always keeping his bill pointed toward him. The courting male then circles behind the other male and copulates with him: he alights on the other male's back, quivering his wings while twisting and vibrating his tail to achieve cloacal (genital) contact. Homosexual copulations are generally somewhat briefer than the three-to-five-second duration of heterosexual matings, and the mountee may fail to cooperate (for example by not twisting his own tail to facilitate genital contact).

Male Anna's Hummingbirds also court and mount both females and males (including juvenile males). These birds usually visit the male's territory to feed on his supply of nectar-rich currant and gooseberry blossoms. If a visiting male lands on a perch, the territorial male usually performs a spectacular DIVE DISPLAY toward him. He first hovers above the other male and utters a few bzz notes, then climbs nearly vertically in a wavering path of 150 feet or more, peering down at the other male. At the top of his climb, he suddenly dives downward at immense speed, making a shrill, metallic popping or squeaking sound just as he swoops over the other male. He then repeats the entire performance several more times. The startlingly loud sound at the end of his dives is produced by air rushing through his tail feathers and is often preceded by vocalizations such as various trilled or buzzing notes. A dive-bombing male actually orients his acrobatic display precisely to face the sun, dazzling the object of his attentions with the shimmering, iridescent, rose-colored feathers of his crown and {642}

throat. On cloudy days, he rarely performs such dives since the mesmerizing visual effect cannot be achieved. After a dive display the other male usually flies off — with the territorial male in close pursuit — and seeks refuge by perching in a low clump of vegetation away from the territory. The pursuing male sings intensely at him, uttering a loud and complex sequence of notes that sounds like bzz-bzz-bzz chur-zwEE dzi! dzi! bzz-bzz-bzz. He may also perform a SHUTTLE DISPLAY (similar to the Long-tailed Hermit's float), flying back and forth above the other male, tracing a series of arcs with his body. A homosexual copulation attempt may then follow, with the male landing on the other's back as in a heterosexual mount. If the mounted male tries to get away, the pursuing male may knock him down, grappling and tumbling with him while emitting low-pitched, gurgling brrrt notes (similar aggressive interactions are also characteristic of heterosexual mating attempts; see below).

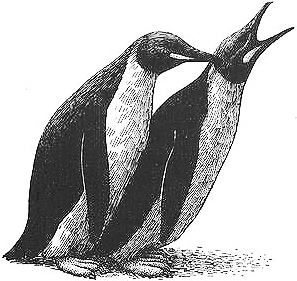

A male Long-tailed Hermit Hummingbird (right) courting another male with the "float" display

Frequency: Although homosexual copulations are not frequent in these species, neither are heterosexual ones, and a relatively high proportion of sexual activity — up to 25 percent — actually occurs between males. During several extensive studies, two out of eight observed copulations in Long-tailed Hermits were between males, while one out of four sexual encounters in Anna's Hummingbirds (where the sexes of the birds could reliably be determined) was homosexual. Moreover, when male Anna's Hummingbirds are presented with stuffed birds of both sexes, they court and mount the males as frequently as they do the females.

Orientation: In Long-tailed Hermit Hummingbirds, approximately 7 percent of territorial males and 11 percent of all males participate in homosexual activity. Territorial males in both of these hummingbird species are probably bisexual, pursuing, courting, and mounting both females and males. Some of the male Long-tailed Hermits who visit other males' territories are nonbreeders (they do not have their own territories), which means they probably do not participate in any heterosexual activity (at least for the duration of that breeding season). Male Anna's Hummingbirds usually strongly resist being mounted by other males, perhaps indicating a more heterosexual orientation on their part (although females also sometimes resist heterosexual mating attempts).

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Heterosexual mating in Anna's Hummingbirds can have all of the aggressive and even violent characteristics described above for homosexual matings — males pursue females in high-speed chases and sometimes even strike them in midair, forcing them down in order to copulate. Some matings are also nonreproductive since they take place outside of the breeding season. Males in this species have their own distinct seasonal sexual cycle, with their sperm production and hormone levels greatly reduced from July through November. Male Anna's Hummingbirds also frequently court females of other species such as the Allen hummingbird (Selas-phorus sasin) and Costa's hummingbird (Calypte costae). Among Long-tailed Hermit Hummingbirds (as well as other species of hermit hummingbirds), males often {643}

"masturbate" by mounting and copulating with small, inanimate objects (including leaves suspended in spiderwebs).

Other than when mating, however, males and females in both of these species rarely meet. In Anna's Hummingbirds, the two sexes occupy distinct habitats during the breeding season — males frequent open areas such as hill slopes or the sides of canyons, females occupy more covered, forested areas. Each female Long-tailed Hermit usually encounters males only once every two to four weeks when she visits the lekking areas prior to nesting. Males of both species take no part in nesting or raising of young. In addition, a significant number of birds are nonbreeders: nearly a quarter of all Long-tailed Hermit males are nonterritorial and therefore do not participate in heterosexual courtship or copulation, while of those who hold territories, only some get to mate with females.

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

Gohier, F., and N. Simmons-Christie (1986) "Portrait of Anna's Hummingbird." Animal Kingdom 89:30-33.

Hamilton, W. J., III (1965) "Sun-Oriented Display of the Anna's Hummingbird." Wilson Bulletin 77:38-44.

* Johnsgard, P. A. (1997) "Long-tailed Hermit" and "Anna Hummingbird." In The Hummingbirds of North America, 2nd ed., pp. 65-69, 195-99. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Ortiz-Crespo, F. I. (1972) "A New Method to Separate Immature and Adult Hummingbirds." Auk 89:851-57.

Russell, S. M. (1996) "Anna's Hummingbird (Calypte anna)." In A. Poole and F. Gill, eds., The Birds of North America: Life Histories for the 21st Century, no. 226. Philadelphia: Academy of Natural Sciences; Washington, D.C.: American Ornithologists' Union.

Snow, B. K. (1974) "Lek Behavior and Breeding of Guy's Hermit Hummingbird Phaethornis guy." Ibis 116:278-97.

--- (1973) "The Behavior and Ecology of Hermit Hummingbirds in the Kanaku Mountains, Guyana." Wilson Bulletin 85:163-77.

Stiles, F. G. (1983) "Phaethornis superciliosus." In D. H. Janzen, ed., Costa Rican Natural History, pp. 597-599. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

* --- (1982) "Aggressive and Courtship Displays of the Male Anna's Hummingbird." Condor 84:208-25.

* Stiles, E. G., and L. L. Wolf (1979) Ecology and Evolution of Lek Mating Behavior in the Long-tailed Hermit Hummingbird. Ornithological Monographs no. 27. Washington, D.C.: American Ornithologists' Union.

Tyrell, E. Q., and R. A. Tyrell (1985) Hummingbirds: Their Life and Behavior. New York: Crown Publishers.

Wells, S., and L. F. Baptista (1979) "Displays and Morphology of an Anna X Allen Hummingbird Hybrid." Wilson Bulletin 91:524-32.

Wells, S., L. E. Baptista, S. F. Bailey, and H. M. Horblit (1996) "Age and Sex Determination in Anna's Hummingbird by Means of Tail Pattern." Western Birds 27:204-6.

Wells, S., R. A. Bradley, and L. E. Baptista (1978) "Hybridization in Calypte Hummingbirds." Auk 95:537-49.

Williamson, E. S. L. (1956) "The Molt and Testis Cycle of the Anna Hummingbird." Condor 58:342-66.

{644}

Woodpeckers

Woodpeckers

BLACK-RUMPED FLAMEBACK (Dinopium benghalense)

IDENTIFICATION: A medium-sized, red-crested woodpecker with a golden back, black rump, and black-and-white patterning on the face and neck. DISTRIBUTION: India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka. HABITAT: Woodland, scrub, gardens. STUDY AREA: Near Chittur, India; subspecies D.b. puncticolle.

ACORN WOODPECKER (Melanerpes formicivorus)

IDENTIFICATION: A red-capped woodpecker with a striking black-and-white face, black upperparts, white underparts, and a black breast band. DISTRIBUTION: Pacific and southwest United States, Mexico through Colombia. HABITAT: Oak and pine woodland. STUDY AREAS: Hastings Natural History Reservation (Monterey) and near Los Altos, California.

Social Organization

Acorn Woodpeckers have an extraordinarily varied and complex social organization. In many populations, birds live in communal family groups containing up to 15 individuals — typically there are as many as 4 breeding males and 3 breeding females in such groups (though nonbreeding groups also occur — see below). The remaining birds in a group are nonbreeding "helpers" that may share in the parenting duties. Within groups, the mating system is known as POLYGYNANDRY, that is, each male mates and bonds with several females and vice versa. In other populations, monogamous pairs as well as other variations on polygamy occur. Little is known about the social organization of Black-rumped Flamebacks, although it is thought that they form monogamous mated pairs.

Description

Behavioral Expression: Male Black-rumped Flamebacks sometimes copulate with each other. One male mounts the back of the other (as in heterosexual mating), bending his tail down and thrusting it under the belly of the other male to make cloacal (genital) contact. Reciprocal mounting may occur, in which a male copulates with a male that has just mounted him. A bird involved in same-sex {645}

mounting activity may adopt a distinctive posture, in which his body is perpendicular to the branch he is perching on and his wing tips are arched toward the ground and hanging below his feet. Males also sometimes drum against a tree trunk prior to homosexual mounting.

Acorn Woodpeckers participate in a fascinating group display that involves ritualized sexual and courtship behavior, including homosexual mounting. At dusk, the members of a group gather together prior to roosting in their tree holes. As more and more birds arrive, they begin mounting each other in all combinations — males mount females and other males, females mount males and other females, young Woodpeckers mount older ones and vice versa. The mounting behavior resembles heterosexual mating, except it is usually briefer and cloacal contact is generally not involved (although genital contact does sometimes occur). Reciprocal mountings are common, and sometimes two Woodpeckers will try to mount the same bird simultaneously. Following the display, group members fly off to their roost holes to sleep. Ritualized mounting may also occur at dawn when the birds emerge from their roost holes. Because many group members are related to each other, at least some of this mounting is incestuous. Female Acorn Woodpeckers often coparent together, both laying eggs in the same nest cavity. Such "joint nesters" are often related (mother and daughter, or sisters), but sometimes two unrelated females nest and parent together as well. Joint-nesting females may continue to associate even if they happen not to breed in a particular year.

Frequency: Homosexual behavior in Black-rumped Flamebacks probably occurs only occasionally; however, heterosexual mating has never been observed in this species in the wild, so much remains to be learned about the behavior of this Woodpecker. The mounting display of Acorn Woodpeckers — including homosexual mounting — is a regular feature of the social life of this species at all times of the year, occurring daily in most groups. More than a third of all female Acorn Woodpeckers nest jointly, and about a quarter of all groups have joint-nesting females; 14 percent of these joint nests involve unrelated females as coparents.

Orientation: To the extent that they mount both males and females in the group display, Acorn Woodpeckers are bisexual (although it must be remembered that such mounting is often ritualized, i.e., it may not always involve genital contact). Not enough is known about the life histories of individual Black-rumped Flamebacks to make any generalizations about their sexual orientation.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

As described above, Acorn Woodpeckers have an unusual communal family organization that can involve different forms of polygamy. In addition, many birds are nonbreeding: more than a third of all groups may not reproduce in a given year, and one-quarter to one-half of all adult birds do not procreate. In some populations the proportion of nonbreeders may be as high as 85 percent. Many of these are birds who remain with their family group for several years after they become {646}

sexually mature, helping their parents raise young; some delay reproducing for three or four years. Other nonbreeders (as many as one-quarter) do not in any way help to raise young. Some groups are nonreproductive because all their adult members are of the same sex: nearly 15 percent of nonbreeding groups have no adult females and nearly 4 percent have no adult males. In addition to the nonprocreative heterosexual behaviors mentioned above (REVERSE mounting, group sexual activity, mounting without genital contact), female Acorn Woodpeckers also sometimes copulate with more than one male in quick succession. About 3 percent of families contain offspring that result from promiscuous matings with males outside the group. Incestuous heterosexual matings occasionally occur as well, although they seem to be avoided — in fact, incest avoidance may lead to a group's forgoing breeding for an extended time. Parenting in this species is notable for a variety of counterreproductive and violent behaviors. Egg destruction is common — particularly among joint-nesting females, who often break (and eat) each other's and their own eggs until they begin laying synchronously. Males also sometimes destroy eggs of their own group. In addition, infanticide and cannibalism occur regularly in Acorn Woodpeckers. A common pattern seems to be for a new bird in a group — often a female — to peck the nestlings to death and eat some of them in order to breed with the other adults in the group. Parents also regularly starve any chicks that hatch later than a day after the others do.

Sources

(* asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender)

* Koenig, W. D. (1995-96) Personal communication.

Koenig, W. D., and R. L. Mumme (1987) Population Ecology of the Cooperatively Breeding Acorn Woodpecker. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Koenig, W. D., R. L. Mumme, M. T. Stanback, and F. A. Pitelka (1995) "Patterns and Consequences of Egg Destruction Among Joint-Nesting Acorn Woodpeckers." Animal Behavior 50:607-21.

Koenig, W. D., and P. B. Stacey (1990) "Acorn Woodpeckers: Group-Living and Food Storage Under Contrasting Ecological Conditions." In P. B. Stacey and W. D. Koenig, eds., Cooperative Breeding in Birds: Long-Term Studies of Ecology and Behavior, pp. 415-53. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Koenig, W. D., and F. A. Pitelka (1979) "Relatedness and Inbreeding Avoidance: Counterploys in the Communally Nesting Acorn Woodpecker." Science 206:1103-5.

* MacRoberts, M. H., and B. R. MacRoberts (1976) Social Organization and Behavior of the Acorn Woodpecker in Central Coastal California. Ornithological Monographs no. 21. Washington, D.C.: American Ornithologists' Union.

Mumme, R. L., W. D. Koenig, and F. A. Pitelka (1988) "Costs and Benefits of Joint Nesting in the Acorn Woodpecker." American Naturalist 131:654-77.

--- (1983) "Reproductive Competition in the Communal Acorn Woodpecker: Sisters Destroy Each Other's Eggs." Nature 306:583-84.

Mumme, R. L., W. D. Koenig, R. M. Zink, and J.A. Marten (1985) "Genetic Variation and Parentage in a California Population of Acorn Woodpeckers." Auk 102:305-12.

* Neelakantan, K. K. (1962) "Drumming by, and an Instance of Homo-sexual Behavior in, the Lesser Gold-enbacked Woodpecker (Dinopium benghalense)." Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 59:288-90.

Short, L.L. (1982) Woodpeckers of the World. Delaware Museum of Natural History Monograph Series no. 4. Greenville, Del.: Delaware Museum of Natural History.

--- (1973) "Habits of Some Asian Woodpeckers (Aves, Pisidae)." Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 152:253-364.

Stacey, P. B. (1979) "Kinship, Promiscuity, and Communal Breeding in the Acorn Woodpecker." Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 6:53-66. {647}

Stacey, P. B., and T. C. Edwards, Jr. (1983) "Possible Cases of Infanticide by Immigrant Females in a Group-breeding Bird." Auk 100:731-33.

Stacey, P. B., and W. D. Koenig (1984) "Cooperative Breeding in the Acorn Woodpecker." Scientific American 251:114-21.

Stanback, M. T. (1994) "Dominance Within Broods of the Cooperatively Breeding Acorn Woodpecker." Animal Behavior 47:1121-26.

* Troetschler, R. G. (1976) "Acorn Woodpecker Breeding Strategy as Affected by Starling Nest-Hole Competition." Condor 78:151-65.

Winkler, H., D. A. Christie, and D. Nurney (1995) "Black-rumped Flameback (Dinopium benghalense)." In Woodpeckers: A Guide to the Woodpeckers of the World, pp. 375-77. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Kingfishers and Rollers

Kingfishers and Rollers

PIED KINGFISHER (Ceryle rudis)

IDENTIFICATION: A robin-sized, crested bird with speckled black-and-white plumage and a long bill. DISTRIBUTION: Sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, India, Southeast Asia. HABITAT: Lakes and rivers. STUDY AREA: Basse Casamance region of Senegal; subspecies C.r. rudis.

BLUE-BELLIED ROLLER (Coracias cyanogaster)

IDENTIFICATION: A stocky, 14-inch bird with dark blue plumage, a long, turquoise, forked tail, and a creamy white head and breast DISTRIBUTION: West Africa. HABITAT: Savanna woodland. STUDY AREA: Basse Casamance region of Senegal.

Social Organization

Pied Kingfishers sometimes gather in flocks of 80 or more birds, and outside of the mating season they associate in small groups. Breeding birds form monogamous pairs, but there is a large population of nonbreeding males as well, many of whom help heterosexual pairs raise their young. Blue-bellied Rollers live in pairs or small groups of 3-13 birds, which are probably extended families or clans; mating may occur promiscuously among several group members.

{648}

Description

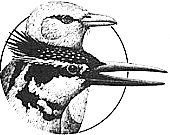

Behavioral Expression: In Pied Kingfishers, two males sometimes develop a pair-bond and may engage in homosexual mounting and copulation attempts. Homosexual mounting can also occur among males that are not bonded to each other. In all cases, homosexual activity is found among nonbreeding males, of which there are several distinct categories. Some males are HELPERS, who assist heterosexual pairs in raising their young. There are two types of such helpers: PRIMARY helpers, adult birds who help their parents; and SECONDARY helpers, who are unrelated to the pairs they help. In addition, some nonbreeding birds are nonhelpers, who do not assist heterosexual pairs at all. Homosexual pairing probably occurs mostly in the latter group, since primary helpers are devoted to assisting their parents and are also often hostile toward secondary helpers, openly attacking and fighting with them. Some homosexual behavior may also take place among secondary helpers, although this is less likely, since such males are usually preoccupied with feeding females in the pairs they assist (though their parenting duties are usually less extensive than those of primary helpers).

A remarkable form of ritualized sexual behavior occurs among Blue-bellied Rollers, and in some cases the participating birds are of the same sex. One bird mounts the other as in regular copulation, beating its wings and sometimes grabbing in its bill the neck or head feathers of its partner. The mounter lowers its tail while the mountee droops its wings and raises its tail, in some cases achieving cloacal (genital) contact. In almost three-quarters of the cases, mounting is reciprocal (the mountee becoming the mounter and vice versa); reciprocal mounting may be more common between birds of the opposite sex, however. Sometimes, mounting with exchange of positions is performed repeatedly, with as many as 28 mounts alternating between the partners in succession. This mounting behavior is often a ritualized display performed for other birds, and sometimes the tail movements and other gestures characteristic of full sexual behavior are more stylized or attenuated. Mounting may be accompanied by a number of dramatic aerial displays (often considered signs of aggression), including acrobatic chases, SOARS (rapid ascents with wings angled in a V-shape, just prior to being "caught" by a pursuing bird), and swoops (breathtaking plummets with folded wings). Birds may also utter loud, mechanical-sounding RATTLES as well as screaming RASP notes during mounting or the associated aerial displays.

Frequency: Homosexual bonding and mounting probably occur only occasionally among Pied Kingfishers. Ritual mounting behavior is common among Blue-bellied Rollers, occurring throughout the year; the exact proportion of mounting that is same-sex, however, is not known.

Orientation: In some populations of Pied Kingfishers, about 30 percent of the birds are neither breeders nor helpers, while about 18 percent are secondary helpers — these are the segments in which male homosexual activity is found, although probably only a fraction of these birds are involved. Although secondary helpers often go on to mate heterosexually, it is not known whether the same is true {649}

of nonhelpers or birds that participate in homosexual activity. However, because of the relatively short life span (one to three years) and high mortality rate of this species, it is likely that at least some males are involved in homosexual activity for most of their lives without ever mating heterosexually.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities